Road to the IGF: Videocult's Rain World

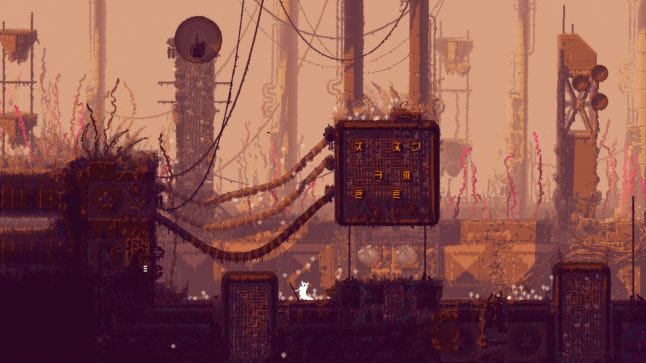

A lonely slugcat has to make its way in a world of predators and lethal storms in Rain World, a game that mixes curiosity, calmness, and terror with its sound design.

This interview is part of our Road to the IGF series. You can find the rest by clicking here.

A lonely slugcat has to make its way in a world of predators and lethal storms in Rain World, a game that mixes curiosity, calmness, and terror with its sound design. As players wander this alien world, they'll be met with ambient sound that coaxes out varied emotions or enhances what the player is feeling as they laugh at the slugcat's antics, wish for its survival, and live in fear of the creatures and rain that can snuff out its life in moments.

This experience in being a lowly creature in the food chain, along with its world-building musical design, earned Rain World a nomination for Excellence in Audio from the IGF. Gamasutra spoke with Joar Jakobsson and James Therrien of Videocult, developers of Rain World, to talk about creating an audio that takes players to an alien world and makes it feel real.

What's your background in making games?

Jakobsson: I have been messing around with making games since the Klik&Play days, always maintaining a project or ten alongside of school. Rain World started as one of those, but evolved into a more serious project.

Therrien: I've been doing game soundtracks and audio for a number of years, but this was my first time doing work on the proper development side as well.

How did you come up with the concept?

Jakobsson: The very initial idea was to make a platforming character that wasn't static upright, but could fall and tumble and crawl. I applied some graphics on the box prototype, and that was the slugcat character pretty much as it still looks. After that, there were a few different ideas for what environment the character should live in, until the world of Rain World popped up. At that time, I, of course, had no idea what the details would develop to be - or how James, whom I had never met at that point, would go ahead with the level design. But I remember very clearly when the idea for the specific mood came to me - the grimy, wet industrial environment, the weird plants, all of that.

If there's anything I'm particularly happy with in the project, it's that despite several years of the project taking very unexpected twists and turns, we maintained a particular mood throughout. Our partnership has also been really great in that regard - I am absolutely unable to work with sound or music, but James has been able to somehow lift the emotional vibe of the world and not only convey it through sound, but build on it and greatly enhance it.

Therrien: Joar's initial Rain World vision and aesthetic was so strong even in the prototype stages that honestly, we just took what was in the prototype and concept art and extrapolated on it for years and years. If you see the first movement test build and the game now, it's basically identical despite huge engine, code, and scope changes . When I came on I had already bought into the project concept hard and drank the Kool-Aid down to the bottom, so there was almost zero "well *I* think we should do this or that", it was entirely "how can I help realize this vision". Probably a rare experience!

What development tools were used to build your game?

Jakobsson: Rain World is written in C#, and exists as a custom game engine that sort of lives inside Unity, using it for rendering, input, stuff like that. I use Visual Studio to develop.

Therrien: Also, for the most part, all the non-music/audio creation tools that I was working with, such as the level editor and all the visual asset stuff, were all built by Joar too. Even the dynamic audio engine! 100% Joar: the game, from scratch.

How much time have you spent working on the game?

Therrien: Far too much! Low estimate is 6 years of non-stop, obsessive work.

Jakobsson: Wow. I really have no idea. Think ... more than you think, and then double that.

Rain World takes the player to a world of unknown nature. What work went into creating the sound effects of the animals and environments of a natural alien world? In creating a believable new ecosystem through sound?

Therrien: Excellent question. That was the big intriguing thing for me when I started on this project. At the time Joar and I were first discussing this aspect, games and especially indie games, were much more simplistic and "gamey", for lack of a better word, in their audio design. Arcade bleeps and bloops and retro concepts were what was popular. That stuff can be charming of course, but I strongly felt that for the moody, immersive atmosphere we were going for in Rain World we would require a much more naturalistic, organic approach to sound design.

In fact, that was even the main reason I reached out to Joar in the first place! I loved the look of his prototype and, I kid you not, had a nightmare one night that the game had come out and the experience was ruined by bad audio. So I shamelessly volunteered myself, lol.

As for the methods, Rain World uses almost exclusively real audio sources for the SFX and ambient audio (the music too, in fact!). For the ambient atmospheric sounds, it's layers upon layers of field recordings of city sounds, wind over empty fields, the buzzing of insects, etc., all subtly colored and flavored with filters and such to give it a sense of cohesion, then set believably for whatever the room or terrain or in game situation was.

For the SFX, it was lots of recording samples of banging on rusty cans or stomping on gravel, etc, to create the base of the sound effect and then blending with synthesized elements to create, say, the springy "woosh" of a jump, so you'd have that effective "game" sound, but also blended so to have it fit somewhat believably in with the natural audio environment.

I think probably what sets Rain World apart in this regard is the level of detail. In real life, our sound world is complex and nuanced, so I sought to replicate that. A basic single-screen room in Rain World might have 8 or 9 different ambient audio layers: A couple of "room sounds" to set the stage: air escaping from a vent, wind whistling by a window, flies buzzing in a corner, machines rumbling under the floorboards, the 60hz hum of electric lighting, flowing water from nearby, etc etc.

As the player moves through the room, the blend of the sound of course changes, giving this sense of a detailed and hopefully believable 3D audio world. The same went for the SFX: rather than a jump sound, how about 12 basic sounds for the same jump action, which then have all manner of variable aspects like Doppler and pitch randomization based on speed and distance cones and such attached? Since I was both ambitious audio director and audio grunt worker I got to take it to whatever absurd levels I wanted to without complaints! Joar indulged my insanity here.

Rain World's music captures various types of mood as players help the poor slugcat in its struggle for survival. What did you want the player to feel through the game's audio? How did it mirror what the slugcat is feeling?

Therrien: A key concept for Rain World was that we wanted the experience to be free from direction and as textless as possible, allowing the player to emotionally project into our little lost slugcat protagonist. So, without text, music became the key narrative and emotive guide. Often it is used to set the tone of a region or location, evoking concepts like wonder or dread or longing; moods we hoped would color the players understanding of what they were seeing. "Why would the rusting hulk of what appears to be an ancient antennae be accompanied by such melancholy music? What happened here to create such a mood?" As Rain World is superficially about exploring the abandoned remains of an ancient civilization, these were the sorts of questions we were hoping to inspire with the music, even if just subconsciously.

On the other side, the music also has to create excitement and spice up action. Since Rain World is, in a lot of ways, an unscripted open-world game, action and combat can come unexpectedly at any time and at any intensity levels. So, how to balance the wish for moody, quiet, ambient open spaces with the need for action-driving beats?

Our solution was to create a dynamic Threat Music system: each region of the game has 9-12 tracks of Threat Music which can fade up or down depending on how much danger the player is in. If no danger, no threat music. Slight danger? Perhaps 1 track, which might be a steady drum beat or subtle shaker sound. More danger will add bass, percussion elements, melodies, etc., until a blaring soundtrack accompanies the carnage.

I have a video with a little demonstration of these audio types below if you'd care to look.

The sound of the rain is a terrifying thing in Rain World. How did you design the powerful, overwhelming fear of the incoming storm just through the steadily increasing sound of the rain? How did you create this single, important sound?

Therrien: My favorite sound! I mean, the game is called Rain World, so we had to deliver on that aspect. It wasn't enough for the rain to simply exist, because in this world, and for these creatures, the rain is the absolute existential threat. Lizards might snap at you and vultures are annoying, but in truth they are just your brothers and sisters, struggling to survive as you are. Here, the rain is oblivion incarnate, and I needed to convey that. We wanted the player to fear the rain and desperately avoid it as the slugcat would.

The rain sound itself is a number of layers of sampled rainstorms at various strengths which fade in as the rain intensifies, later adding in versions with various gritty elements, distortion, and so on as it moves beyond the natural and builds into the dreaded wall of watery death. The final sound elements added are actually heavily pitched and distorted pipe organ chords, for that totally biblical wrath-of-god vibe.

Have you played any of the other IGF finalists? Any games you've particularly enjoyed?

Jakobsson: I haven't played many, just coming out of working on the RW1.5 update! But one I did play was Nathalie Lawhead's Everything Is Going to Be OK - the aesthetic is just beyond great, that's my excellence in visual art pick for sure.

Therrien: Oh, absolutely, I love a lot of this years nominees. Night in the Woods, Getting Over It, Everything is going to Be OK, Tacoma, Cuphead, Uurnog Uurnlimited. Honestly, I haven't played enough of them as we've been working too much. But personally, I think it was a banner year for games.

What do you think are the biggest hurdles (and opportunities) for indie devs today?

Jakobsson: I'm notoriously bad at "being in touch with the field" - so take what I say with a pinch of salt! I would think that the situation is that the barrier of entry is lower than ever - everyone has a computer and access to YouTube and stackoverflow, so you reading this can absolutely get started with gamedev this very evening if you decide to. With that comes saturation - there's just so many games out there, and the real hurdle is to make people notice your game. If we suppose we are indies, large scale marketing is mostly out of the question so we have to catch people's attention by being different and interesting instead.

Also, a thing that worked very well for Rain World is keeping a consistent devlog - then people can build a long-term relationship to the project. Devlog tips: Post every day, even if you barely made any progress. Try to always have a picture, or even better, a gif of what you're working on. And be technical, the devlog is as much for you to keep track of your own progress as for others to read, so really let it be a development log and not some kind of marketing blog or hype vehicle. Don't know how generally applicable that is, but that's how I did it!

Therrien: From my perspective, the biggest hurdle in actually shipping a game is finding people who are reliable and that you can work with for the long haul of a project. Games take years to produce, with many many ups and downs, absurdly long hours, and little guarantee of success. It's impossible to make progress if people are leaving or having to be replaced for various reasons.

With Rain World, I was very lucky to have a partner and later a team that was hardcore dedicated and committed to seeing this vision to fruition. The plus side is that, tagging onto what Joar said, the tools are all available and you certainly can learn as you go. So, the opportunity is there to find like-minded people who you get along with and just go for it! You don't need a degree or some fancy portfolio; just work ethic and a dream. If you have that, you can overcome anything.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like

.jpeg?width=700&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)