Road to the IGF: Question's The Magic Circle

Road to the IGF 2016 continues as Question's own Stephen Alexander, Kain Shin and Jordan Thomas chat with Gamasutra about The Magic Circle, the IGF award-nominated game that lampoons game development.

This interview is part of our Road to the IGF series. You can find the rest by clicking here.

As the independent game industry swells and developers in general grow more comfortable expressing personal experiences through their work, we're seeing more games truck with the realities of game development itself.

Last year games like The Beginners Guide, The Writer Will Do Something and Dr. Langeskov, The Tiger, and The Terribly Cursed Emerald: A Whirlwind Heist afforded players a unique perspective on what goes on behind the scenes (sometimes figuratively, sometimes literally) of game development.

Among them, Question's own The Magic Circle stands out for affording players an external perspective on a (fictional, heavily satirized) game project and prompting them to "fix" it by using a suite of mechanics to overcome in-game obstacles. It's a darkly comedic tale of a game gone awry, one that earned a nomination for the 2016 IGF Excellence in Narrative award.

The game shares much in common with first-person immersive sims like Deus Ex, Bioshock and Dishonored, unsurprising in light of the fact that Arkane expat Kain Shin and former Irrational devs Jordan Thomas and Stephen Alexander compromise Question's core staff.

In a recent conversation with Gamasutra via email, the trio explained where, precisely, The Magic Circle comes from, and how going indie to make a game about game development has changed the way they view themselves and the industry at large.

What's your background in making games?

Alexander: I started as an artist at a company called Incredible Technologies working on a game called Golden Tee Golf. From there I got hired as a visual effects artist at Irrational games based on effects I had done for a video pinball game that never saw the light of day.

I was the FX artist for the first Bioshock which was where I first worked with Jordan. On Bioshock Infinite I moved into the combined role of Lead Narrative Artist and Lead FX Artist and after we shipped Jordan and I started talking about branching out and starting our own company.

Thomas: Game journalism, then hired as a teen by Psygnosis to write copy. They paid well -- but folded within a year. First real design gig was at Amaze, on Harry Potter for PC; I learned Unreal there. Then to Ion Storm Austin for Thief 3, where Randy Smith and Emil Pagliarulo taught me to be an actual game designer.

I made a scary level that some folks noticed, got promoted to Lead. ISA was shuttered in 2005, then I worked on all the Bioshocks - the second one was my first time directing a game, did pretty well. After Infinite, though -- felt it was time to work for myself and partners. That's Question.

Shin: I started out in 2000 working on casino games, and then got my first real game job at Ion Storm Austin working on Deus Ex: Invisible War followed by Thief: Deadly Shadows. After that, I worked at a few studios for a few years making sexy unannounced projects that remained unannounced until I became a Lead programmer at Red Fly studios on Mushroom Men.

I wanted to get back into immersive sims, and so I joined Arkane studios where I worked on several projects, the last one being Dishonored where I served as core AI architect and gameplay programmer until it shipped in 2012. After that, I left Arkane to work at Harmonix as a gameplay programmer on an unannounced project as well as a project that was announced (Chroma). I went merc in 2013 before officially merging with Stephen and Jordan in 2014.

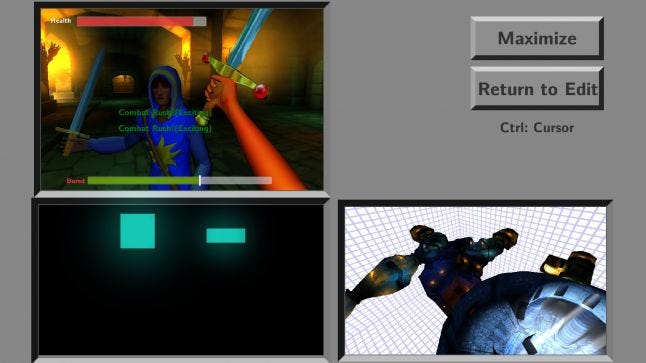

What development tools did you use to build The Magic Circle?

Alexander: We made the game using Unity as well as a few pieces of middleware, notably A* Pro, SECTR, EasySave, and i2 Localization. On the art side I primarily worked in 3DSMax, Photoshop, After Effects, and Motion Builder for getting our Mocap scenes in the game.

Thomas: For writing, I used Adobe Story at first, because I owned it as part of a package of tools - eventually though, its limitations drove me back to Final Draft, money well spent. For the mocap scenes, we didn't end up using it but: hilariously for a little while we had some mo-cap animation that was captured entirely on two Kinect cameras. It was… fugly. Too rough even for the joke framework to excuse, and we replaced it with pro work from the awesome folks at Halon. Pat, our sound guru, I think uses Pro Tools for effects and Vegas for dialogue.

Shin: PC builds of Magic Circle are developed in Unity 4.x, but we are developing the console versions in Unity 5.x. Visual Studio is my preferred IDE. Steam integration was done using the excellent Steamworks.NET library, and Stephen mentioned the rest of the middleware we used.

How much time have you spent working on the game?

Alexander: We started working on the game in Spring of 2013, and went into early access in late Spring of 2015. All told it was about 2 years and change for development.

Shin: I started work as a part time volunteer on The Magic Circle right after I left Harmonix in August of 2013. I stopped doing external contracts and went full time with Question in July of 2014… about a year before shipping.

How did you come up with the concept?

Thomas: Stephen and I kicked around some assorted darker concepts first, but at the time, we had more than our fill of brooding and grim. Somewhere in that list was a thumbnail idea from me about the often snarky whiteboard graffiti that shows up in game studios. That was the idea, that you were the hero of an unfinished game that was still on a whiteboard.

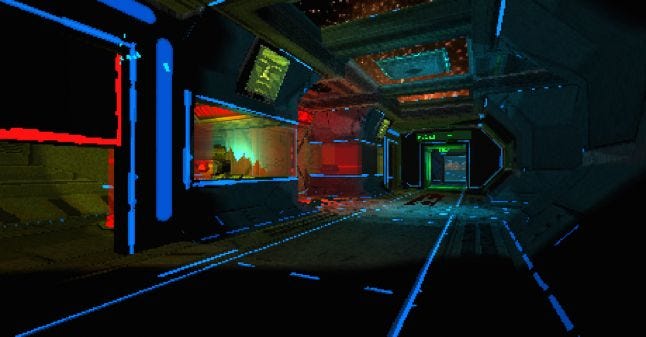

Something lighter, self-mocking and more meta resonated most with Stephen, which was all I cared about. So TMC was born. Over time we moved away from a literal whiteboard and towards the idea of actually inhabiting the software as it was being altered in real time, and that liberated us to add sections like the '90s-inspired "space dungeon", complete with rendering artifacts of the era.

It ended up being the right choice, because we could show rather than tell (and ideally in some cases, literally play) the old discarded versions of the fictional game that our story claimed had been in development hell for 20 years.

What were the practical consequences of making a game that satirizes game development, both personally and professionally?

Alexander: On a personal level it was fun to be able to step back and present an exaggerated version of our failures as people and creators. So much effort usually goes into appearing like you know exactly what you are doing that to shine a light on how false that often is was liberating in some ways. Professionally it has been mixed, in the sense that The Magic Circle doesn’t necessarily scream “mainstream entertainment”. As a result, our sales haven’t been as high as we would have liked them to be as it relates to putting Question in a comfortable place financially. On the other hand, we have proven to ourselves that we can make a compelling game in a reasonably short amount of time, which gives us a lot more confidence going forward.

Making something that lived so completely in the “meta” space was a bit of an exorcism as well. I think we all had an interest in and taste for those kinds of stories, and making a game that pushed that as far as we could has allowed me (I can’t speak for everyone) to no longer feel the need to operate in that arena for quite some time. I’m psyched to make something more straightforward, at least as straightforward as Question can realistically be while still making something that excites us. We are fans of the weird and alien.

Thomas: Writing-wise it was a full 500 percent harder than I thought it would be. First, everyone and their mom's dog assumed it was a screed against former colleagues, or a true confession with fake names - so we spent a lot of time rewriting in favor of more universal flawed-creator themes, sometimes at the cost of specificity. Secondly, we did run into a lot of terminology collision "which game, the real Magic Circle, or the fictional one? Who do the fictional devs mean when they say the Player?" et cetera.

The real suckerpunch was that the development cycle for TMC spanned one of the darkest times for gaming culture that a lot of people can remember, and so suddenly this light-hearted satire we set out to build was drawing influence from the very scary, too-real way in which creators and fans can come to blows. The conflicts that flare up over who really owns these worlds, what that says about their identity, and who they're willing to share it with. And that topic was way bigger than we were; our little few-hour story became editorial Tetris with what felt like a gun to our heads. Trying not to let any one fictional dev or fan perspective be the clear "right" answer, letting the player be the reasonable midpoint between extremes, and so forth.

We could have tried to ignore it completely and stay breezy, but speaking personally, I couldn’t look away. I thought about it every day, maybe to a fault. During previous game culture quakes - like say, the Jack Thompson saga - I never had relatives asking me point-blank what is wrong with gamers like I did during 2014. Without naming the beast, that crisis was more about gender than TMC could meaningfully take on, so far into development. But that capacity for mob mentality among all of us … was in the creative mix whether I liked it or not. So for some of our audience it became more true than it was funny. We tried very hard not to let The Magic Circle succumb to cynicism, though. It ends on what I hope is a pretty sanguine note.

The one big upside of that heartache is that I'm not a career comedy writer, so TMC doesn't entirely live or die by how well I landed a joke. Thank goodness the members of our voice cast are so naturally comic, they helped us course-correct in the moment and often saved my ass. The IGF nomination shocked me. I'm just glad that some part of it spoke to anyone.

Shin: Working on a game that shined a light on tensions within the creative process shined a light on our own process as we were making the game. Ish, Maze, and Coda all represent versions of ourselves at various points in our career.

We had each come from backgrounds working at studios full of hard hitting alpha game developers who were very good at their jobs and had extremely strong opinions about their aspect of the game. The concept of art ownership was a topic that really resonated with me when Jordan first told me about The Magic Circle. Tense environments full of passionate developers typically evolve into process-heavy cultures where meetings, A/B testing, and other methods of enabling consensus were required before taking any step forward.

“You want to add something to the game? Write up a task and make sure it gets reviewed by leads so that we can track it for you. The leads will discuss your proposal in the next leads meeting to let you know if you can add that feature. Don’t forget your time estimates.”

After many years of that, we essentially rebelled against that culture we were lampooning (color schemes needing approval before the game can have color) and totally went the other way of developing more like three wild west cowboys who really trust each other to do whatever needed to be done however we deemed fit. It worked well, for the most part. We failed often but recovered quickly. Still, that wild west method is not sustainable, and we are constantly refining our methods in order to get better at maintaining work/life balance. That experience of working in both extremes of the process spectrum gave us some much needed perspective on what we want the shape of our working days to feel like.

Have you played any of the other IGF finalists? Any games you've particularly enjoyed?

Alexander: I absolutely loved Her Story. Going into it I really didn’t think it was going to be for me, but was amazed with how robust the underlying system was, and how much freedom it gave me as a player. The fact that it was FMV had primed me to expect the opposite, so it was a treat to have that expectation turned on its head.

Thomas: Catching up with several, and since Stephen took Her Story, which has made some long-term changes to the way I think about the "rules" of game storytelling... I'll talk about Darkest Dungeon. Damn, Red Hook, I mean, take a bow. To have constructed something that good in Early Access, first of all - still way outside the norm. And then, with a relatively small studio, to combine elements of unforgiving permadeath roguelike stuff that I usually can't go anywhere near, with the RPG growth systems that offer such comfort and continuity... all wrapped up in a lovably purple lovecraftian tone.

I mean, that narrator guy? I just want to hug him and hear him describe it like "THE ABYSS, WITH SIGHT INSENSATE, DRAWS ME NIGH - UNTOLD LIMBS, QUESTING BEYOND FLESH TO CLUTCH AT MY SECRET SOUL!"

Shin: I played The Beginner’s Guide and thoroughly enjoyed it. It’s amazing how context can make such a difference when playing something that is broken by design, yet meaningful to anyone who has ever made something as an act of expression.

Don't forget check out the rest of our Road to the IGF series right here.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like

.jpeg?width=700&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)