Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

The veteran game creator on the state of design and writing, why social is the most important new frontier in gaming, and how production techniques born in the early days of games can be superior to today's methods.

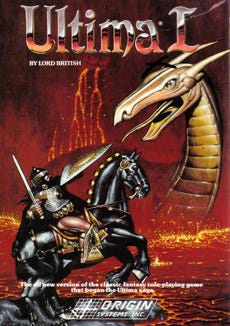

Richard Garriott is best known as the creator of the Ultima RPG series, and he says that his experiences in the early days of game creation give him the multidisciplinary oversight into major content problems that today's designers often lack.

He's turning his attention from major MMOs, in the wake of the closure of his long-in-the-coming, short-in-the-operating Tabula Rasa, and instead joining the ranks of developers moving into the social gaming space -- a place where he sees not just business opportunity, but also a place to aim expertise honed both in the early days of gaming and at the onset of the MMO revolution.

His new company, Portalarium, will be a test of his ideas about game development, which he shares freely in this wide-ranging interview.

Conducted at the DICE 2010 summit, where he delivered a lamentation on the state of games writing, this in-depth Gamasutra interview with Garriott takes in his view of the mainstream games industry of 2010 and where the real opportunities lie -- and why.

Why Facebook?

Richard Garriott: Well, the target is not specifically Facebook. The target is really what I would call broadly the explosively growing market -- the new market of players -- which I'll call broadly casual and social network players.

You know, I kind of look at it and go, "I feel like I've now lived through three major shifts in the gaming industry." Number one is the beginning of the industry, [laughs] you know, where I was lucky enough to be one of the first developers of games. And so, with that came great opportunity and revolutions.

The second one was the emergence of online gaming. Now, I would argue that Ultima Online was a major stepping-stone in convincing people that online gaming was relevant. At the time I was trying to get it going, no one supported it. It was very hard to get going, but when it finally shipped, it ultimately ended up making ten times the revenue of all the previous Ultima games combined.

That has now for the last decade been by far the dominant growth area of gaming at all. I mean, look at things like World of Warcraft, and it's now ten to a hundred times bigger than Ultima Online. But if you look at this new casual and/or social media gaming, a lot of people in this building still either pooh-pooh it or don't get it or don't understand it, yet already the number of players on these games is dramatically in excess of even things like World of Warcraft.

The amount of money flow on this side of the fence is already dramatically in excess of almost any game anybody in this room ever develops. And yet, you know, people still here are still in the mode, just like in my mind they were with online gaming before the models were proven, thinking, "Oh, you know, the quality level is not there yet," or, "Oh, the types of games offered really aren't interesting to me yet."

The amount of money flow on this side of the fence is already dramatically in excess of almost any game anybody in this room ever develops. And yet, you know, people still here are still in the mode, just like in my mind they were with online gaming before the models were proven, thinking, "Oh, you know, the quality level is not there yet," or, "Oh, the types of games offered really aren't interesting to me yet."

And I'm going like, "Well, yeah, that's true -- it might not be yet, but I assure you it will be and very soon. And it's one of these coming juggernauts that you either need to learn to understand and participate in the evolution of or you're left behind, just like online gaming."

What is your ultimate goal for your company right now?

RG: So, I believe the casual gamer and the social gaming platform represents the largest ever yet seen emergence or change within the gaming industry. And all of us in the development community have a choice to either participate and lead in this journey or get left behind.

I believe that my group, which helped start gaming back in the early days of Origin and Ultima that helped begin and grow the online gaming space, which has been the main motivator for the last 10 years, is perfectly suited to also jump in to contribute here with this new emergence. And so I believe we'll be able to bring very high quality play experiences to a consumer base that is growing the fastest and demanding play options faster than any previous group has had.

It's interesting to me -- it seems a lot of people from that era that feel the same.

RG: We were just talking to Sid Meier.

Sid Meier. Steve Woita. All these people are getting back in there because...

RG: Because we did it. And I think everybody else is still a little too egotistical to realize it.

I think there's a lot of reluctance based on the fact that a lot of game developers still make the games they would want to play, and in general, games like FarmVille are not going to fill that particular need.

RG: I agree. And by the way, I don't play FarmVille, personally. However, for example, I can tell you that in this last year, almost 100 percent of my gaming as an avid gamer has been on my iPhone. But I've tried every portable platform that's existed, and none of them were terribly good, but finally we have a platform where lighter mobile games are compelling even to a hardcore gamer.

The way we find this market, the key thing about the casual and social gaming market to me, my definition of it says this: "What's important to these users is not the game fundamentally; it's really their friends." So, the first thing you have to realize is their friendships and networking with their friends is the dominant activity.

So, to find them, you have to go into that community. And then when you decide that you have presented them something entertaining, your friend has to be able to say, "Hey, I found something that's fun. Check it out," they have to be able to send you a link.

They have to be able to download and check it out yourself with no cost, never going to the retail store, never sitting with a long download, never with an instruction manual, never with a tutorial. You have to sit down and play it.

Well, in my mind, every online game that we've already made to date would be a better game if I could pick it up for free, I could download it immediately, I could launch it without any installs, etcetera, etcetera. So, the things the new market is demanding is actually a benefit to every game we've already made in history.

And as you make these games, a lot of those people will come along the ride. A lot of them will be immersed with gaming and want to play more. Some of them will stay light; some will increase their journey. But either way, it's going to be radically market-expanding, and the quality of the offerings is also going to go up very quickly.

One of the things that the portable area is going to be able to do, is that the majority of offerings that you see today on these social media networks are all developed on things that were great common denominators like Flash and Java. And the reason why those were great initial foundations is because it's ubiquitous. You can run it on IE or through Firefox or Safari or on your iPhone eventually. It's easy to transport thing you write there.

And the engine is already designed for you, and there's books written on it and etcetera. And so it makes sense that that would be the first place that people would build games. But the results of those games don't provide you with the same what I'll call graphical power that you do out of a more customized engine, and I would also argue that the user interface, what I'll call the tactile feel that you get when you play a lot of these earlier games, aren't yet up to years of iteration of gaming that we've already done in more hardcore games.

And so I actually think it's actually going to be fairly straightforward for those of us in the traditional gaming market to bring sensibilities of user interface, of graphic quality, of engine performance as long as when we arrive on the scene, we also respect well those fundamentals -- I've already mentioned what I believe that market is -- and then we offer a palette of everything from very simple games like poker and farming or whatever else, as well as a full suite of... to my mind, it could be any MMO you pick, as long as it doesn't violate those premises.

In terms of the UI and kind of backend concerns in the existing social network games, what do you think are the main areas that need to be improved upon, and in what way?

RG: Well, I would think this early generation of social games that exist, the thing they've done brilliantly is that they respect and enhance the social ties of groups of friends within a social network. So, they're doing a very good job of every time I log into one of those games, you can see the kind of next level of crafting that people are learning to how to help bond people to each other, and I'm trying to make sure we learn those laws very quickly, too.

The place that I so far see so little progress on has been the recognition that, if you have the option of two games that are otherwise identical, and one of them is in fact physically just difficult to use -- hard to install, unreliable to install, graphically inferior, obtuse user interface, inelegant or less beautiful than the other -- of course you're going to pick the one that's more beautiful and easier to use.

And I see so far less progress in that area than in what's clearly the core of social games, which is the social part. That part is learning is going very quickly. But strangely, and I think the reason why, by the way, is the people that are making these games are this new breed that gets that, but aren't members of this group [traditional game developers] yet, so to speak, and very few people in this building have chosen to back them up.

It's interesting to me looking at some of these earlier offerings and seeing that the graphical quality isn't quite there -- and that in many cases, it doesn't matter. I don't believe that it won't matter, but I believe it hasn't really mattered yet in many cases.

RG: Well, no. And by the way, that was true... about Ultima Online. So, Ultima Online, we made by using... We were on Ultima 9 at the time, but we used Ultima 6 graphics literally to build Ultima Online. And so the traditional press, all the press in this building, panned it. They went, "Here is a game. It looks three years old. Who gives a flip about playing with other people. It's irrelevant."

And guess what? It wasn't irrelevant. It was the harbinger of things to come. And the same thing's happening right now in social media.

Do you think that story has any kind of place in this arena?

RG: I do. I was asked to play the anti-story role during that debate [at DICE]. And so hopefully I represented the anti-story side pretty well. But fundamentally, I'm a story guy. But I was correctly articulating what I thought the challenges to doing good story were, which is that it's almost never done well and it's rare that the marketplace has rewarded good story. So, I think those are true.

That being said, I actually think what takes games out of being an irrelevant way to spend some time and puts it into literature and meaningful life experience is to put good story in it. And so for me personally, I think it's a really big deal, and I think it absolutely can be done on online interactive environments just like we barely are able to do it now in solo player gaming experiences, but it's definitely a big challenge.

What about the stories that exist between the players, versus top-down narrative?

RG: So, the analogy I would give you is the early days of Dungeons & Dragons on paper. I was one of the earliest adopters of Dungeons & Dragons on paper, and every Friday and Saturday night throughout my high school time, we would have a group of 30 to 40 people that would play at my house, my parents' house, usually in two or three or four games at once in different rooms for years.

But as the game gained popularity, an interesting thing changed. Early Dungeons & Dragons, no one cared about the rules. No one cared about what your +2 or +3 sword was because it was irrelevant. What really mattered is if you had a great gamemaster who was weaving a great story you all got to play your part in.

And if your team did something that was fun and clever and would not have worked, the guy would roll some dice back here, but it worked because it was fun and clever.

If you were doing something really stupid or boring, it didn't work, funny thing. And so what it became is a dialogue discourse between a great gamemaster and engaged players.

Well, once D&D became more and more popular and you ran out of good storytellers for gamemasters, it devolved, in my mind, into the [talks with a lisp] "Well, I'm standing behind you and I've got a +3 sword, and I've got a slight advantage because my dexterity is a little higher", and they do complicated calculations, then once every five minutes, roll die, and say you win. Which I think it not roleplaying.

It might be a fun game... This is my personal definition; most people don't adhere to this. Diablo, great game. Loved it. For me, I use the term "RPG" for it because it is a stats game. It's a "Do I have the best armor equipment compared to the creature I'm facing?" There's not really any story for it. It's a great challenge reward cycle game. Blizzard, by the way, does the best challenge reward cycle games I've seen.

On the other hand, Thief or Ultima are role-playing games versus RPG -- which I know stands for role-playing game. When I think of a role-playing game, it is now where you are charged with playing an actual role and qualitative aspects of how you play are every bit as important as what equipment you use. That's what I find most interesting. It's a lot easier to do stories there.

On the other hand, Thief or Ultima are role-playing games versus RPG -- which I know stands for role-playing game. When I think of a role-playing game, it is now where you are charged with playing an actual role and qualitative aspects of how you play are every bit as important as what equipment you use. That's what I find most interesting. It's a lot easier to do stories there.

And while I think your question really came from what about the story that has naturally evolved between players, clearly that's what's profoundly important about any shared experience.

But if you only rely on that, if you just create a sandbox and say, "You guys make your own stories," it goes back to D&D. There's no context. There's no guidance. There's no showcasing. A good game should constantly lead you over the next hill to see what's on the other side, and it's got to be something of wonder that you and your friends all get to share.

The interactive dialogue in Fallout 3 is not amazing, but it has great scenario design. I feel like as an industry we're better at doing that than delivering actual narrative, written story.

RG: While I think narrative, written story is an important component of good narrative -- which doesn't have to have written story. I think as an art form, we need them all [to be] strong, like they are well-developed in the cinematic industry.

But there's no question. I think often, just what I call "ad hoc" -- what feels to you is ad hoc discovery -- but in fact was the designer put it there near enough for you to bump into and then made each of those encounters have some special response based on the context of where you've been and who you are, I think is very powerful. And I agree, we have some examples, like apparently Fallout 3 has, that begin to showcase that.

One idea that I had for how to make interactive dialogue better -- I'm just curious to bounce this idea off of you -- is iterative dialogue writing, wherein you write it to the best of your ability, and then you play through it properly in the game and then do a re-write based on how it works contextually.

RG: Well, I think as a process that absolutely is necessary. I think that would absolutely give benefit. I would add to that and go, you know the experience you described in Fallout? What was so positive about that -- and again remove from your mind whether it was a text interaction or an event interaction -- because in my mind, both of them advance your state of belief about yourself and your state of belief about the world and where you are and the Joseph Campbell hero's journey arc, so it could be any of those processes.

But the things that almost all games do so poorly that you've uncovered with your example of Fallout [having interesting events but poor dialogue] is most dialogue in most games are you're told to go to location A, you might find some monsters on the way to location A, but there's nothing relevant story-wise to your growth as an individual is going to happen on your way to location A, and when you get to location A, there's generally one real outcome, which is go to location B.

And I don't care how good a storyteller you are, that's never going to be very interesting. You're never going to feel like you've really participated in a truly meaningful way unless you discover things on the journey from A to B, and also when you do get to A and meet that person and have dialogue with, some form of discourse with, that it again has some outcome that for you will be unexpected, as often is not.

If you think about it in the real world, when you research a problem, you might know, "Gee, to find some information, I might need to go to France, where she lives," but you might not know exactly who to talk to, exactly what question to ask, and exactly what company to go and investigate. That's the joy of discovery. You have a general indicator, France, but you don't know what you're going to do when you get there. And that's the joy and excitement of being there. You're like, "Wow, I'm going to have to figure out what it is."

I have heard that you in the past did a scenario wherein the combat wasn't so much important as the way you were comporting yourself.

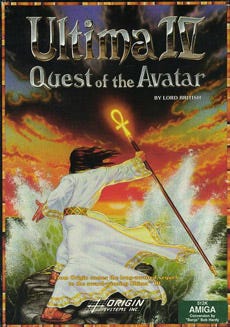

RG: Yes. Ultima IV... Here's the challenge and reward of doing that. What's interesting about Ultima IV is it was very different than any other game I'd made previously, although I've tried to incorporate many elements of that in future games.

When I was writing it, I wasn't sure anybody would get it. When I would explain it to friends and family, they absolutely did not get it, and yet it was the first number one best-selling Ultima I ever did by far. It's really what put Ultima on the map.

What's interesting about it is when you create a game around combat, it's pretty easy to go, "You know, you have weapons that go from wimpy to tough. You got armor that goes from wimpy to tough. You got creatures that go from wimpy to tough. And my skill and experience is going to go from wimpy to tough." So, it's just this feathering of constantly increasing challenge and reward. It's a system you can put aside and say, "We're done."

When you think of the movie Star Wars, what's interesting about it is it's not the same battle over and over again, just a little tougher. There's actually a story arc. Each challenge is unique compared to the previous challenge.

Well, that means, in a gaming sense, you need to code it uniquely in many ways. It's not a system anymore. Or if it there's any systematic-ness to it, it's a lot more elements and a lot more moving parts. It's a lot harder to balance than just everything gets tougher.

So, what I did with Ultima IV is I actually created a game where the game told you, in words, that it was going to be monitoring your behavior. But when you did deeds good, bad, or otherwise, there was no point system that you were aware of that was going up or down. And so you could never be sure when you were being tested and when you weren't.

So, what I did with Ultima IV is I actually created a game where the game told you, in words, that it was going to be monitoring your behavior. But when you did deeds good, bad, or otherwise, there was no point system that you were aware of that was going up or down. And so you could never be sure when you were being tested and when you weren't.

And some tests would be easy for me to do. Like if you stole money from a shop, that's pretty easy for me to test, so I'm going to record it. I'm not going to tell you. I'm not going to stop you. I'm not going to tell you, but I am going to record it. It wasn't really easy to lie to somebody and really test it very well, you know what I mean? Even if I set up one case in the whole game where you could, I couldn't make a system out of it.

But again, I at least made you think it so you'd be worried about it. So, I the entire overarching part of the game was to create this sense of, "Hey, I'm responsible for my own actions in this game, and some of them, an unknown fraction of it, is going to reflect on how the world reacts to me." If you cheated that NPC, later on, you were going to back and need something from that NPC, and he'd say, "I'd like to help you, but you're the most dishonest thieving scumbag I've ever met, so no way."

Here's where the Ultima IV epiphany happened for me. My previous games -- Akalabeth, Ultima I, Ultima II, and Ultima III -- I published all but Ultima III through other publishers. Ultima III was Origin's first game, my company's first game. That was the first time I got letters, what you might call fan mail, from people. And fan mail in our industry is one paragraph of, "Hey, I really like your game," and usually pages of "Here's what you did wrong," or, "Let me tell you how to make your next game."

But what became clear when I would read that mail is how people were interpreting my games in a very different way than I had made them, or they were interpreting things into it that just weren't there. They were just reading things into the game.

I was like, "Wow, it's fascinating how much people are reading between the lines. It's just not there." And also, I was going like, "Okay, the storyline for Ultima I: go kill Mondain the wizard, who sits in his castle and waits for you to come kill him, and you go loot corpses on the way to get there and probably take advantage of villagers on the way. Ultima II: Go kill Minax the enchantress, his lover, and on they go. Pillage and plunder. Ultima III: Go kill Exodus, their offspring, and pillage and plunder on the way."

And I'm going like, "God, I'm so tired of telling this story." And, by the way, that's still the same story almost every game still has to this day. And I'm going like, "Okay, there's got to be more to life than writing the go kill the evil wizard story." And combine that with the fact that people were reading so much into my games that was just never there, and they were playing by pillaging and plundering a lot more than I thought they were.

And so I'm going, "Okay. I'm going to make a game where the world..." I really had no moral message I was trying to tell. What I was trying to do was craft a world where the world responded to you in the same way the real world responds to you. If you behave like a jerk, no one's going to like you and no one's going to help you, and you're not going to be successful. And thus laid the groundwork for Ultima IV.

I also heard you once say you really enjoyed programming; it was your preferred aspect of game development. Is that the case in the past? How did you wind up getting to this situation of much more narrative and design?

RG: Yeah, okay. Here's the truth behind that then and I think I know where that came from. You know, my first five games I wrote by myself, so I was the programmer, I was the artist, I was the terrible writer, I was the sound effects engineer, and I was the marketer. I wrote the documentation, et cetera.

But since then, on we started having teams. The first artist we hired and every artist we've ever hired has been a hundredfold better artist than I ever was. I could literally just use stick figures. The first writers we hired from an English mastery standpoint were all head and shoulders above me.

Programmers, on the other hand, were different. I was actually a good programmer. When we would hire programmers, I felt comparable to them in skill, though I no longer program. But I could, I believe, if I'd kept up the skill, so to speak, be a good programmer. But now every programmer we hire could run circles around me.

Design is the one very unusual case. In design, I can name in the industry only a handful of people that I think are as good or better designers as I am. And it actually less a statement towards what a great designer I believe I am -- because I still believe I make plenty of mistakes and I'm only so-so at it -- but rather how hard the problem is and how unique a moment in time I began.

Because since I was the programmer, artist, designer, etcetera, it means that I now truly understand the trade-offs between those disciplines, and I understand what's important about design versus if you look at most designers today, they don't get a chance to be all those different skills, and most everybody just thinks, "Oh, I love all these games. I've got my great idea for a game. I can't program and I can't draw art, so I'll be a designer."

And so designers have no job qualifications really, if you know what I mean. And so everybody wants to be one and nobody's skilled at it.

Hopefully it's slightly changing now that engines are getting more usable -- for example, in the console games space with Unreal. The scripting is much easier for people to use now. And also in the independent or Flash gaming spaces, where there are game makers and there are ActionScript libraries that can help people get there.

RG: It still requires design skill. One interesting thing about designers... most programmers worked hard to become a programmer. I mean, they spent years studying it. Most artists were somehow born with some natural low-level talent -- I don't understand how that happened -- but then they also spend years honing it. Most designers, by the time they decide to design their first game, have not put in the years of labor to become a designer that those other skills already have.

With or without any tool advantage. More importantly, when I sit down to do a design -- which is my favorite part by the way, not programming -- when I want to design, for example, a symbolic language to include in the game, which I love to do, I will go buy an entire research library on the subject, and I will pore through that subject for a month, because even though I wasn't an expert on it, the only way to successfully include that area of design is to truly become as close to a world-leading subject as it possible, because I'm competing against literature, from a qualitative standpoint.

Almost no other designer that I have ever know does that level of research to this day even though I go talk about it all time. Whenever I talk at GDC or talk to designers, I go, "It's labor. You've got to sit down, and if you're going to talk about any particular subject through your design, you have to become the expert in that area. And if you're not, you're just going to be retreading the same ground everybody else has done, and it's not going to be interesting."

That might be where something of a programming mindset may come into play. I mean, designers don't tend to be research and development oriented.

RG: Right. Designers tend to be gamers who want to fix what they think was broken in the previous game. But that's not the way to be a great designer.

Similar to your point of storytelling not necessarily being rewarded, do you think that many players even notice?

RG: Well, I think, for example, I didn't see Fallout 3, but I'm guessing it also looked and sounded and played very well. Therefore, it's a good game all the way around.

What's interesting about games, especially hardcore games -- the core of what we do -- is gamers aren't really forgiving of sucky aspects of any game. So, just because you have good story is no excuse to be less than pretty close to state of the art on graphics, sound, action, etcetera. And each of these is really hard to do. It's hard to do good graphics. It's hard to do good sound. It's hard to do goo action. And story is extra hard.

And so, that's why I think it's missed a lot, because it's harder than most other aspects and it gives you no additional reward. You can't throttle down on your spending on those other areas to do a pretty good story. You can a little bit, but not much.

In my experience, gamers will tend to have a strong response to graphics they perceive to sub-par or physics that are wacky, but I'll get all up in arms about a story that I think is irresponsible or bad or poorly written, and I'll see nothing written online about it.

Native English speakers have so little interaction with the written word, speaking properly, and grammar, I sometimes feel like they wouldn't know a good story from a bad story.

RG: You know, and I think fundamentally we share the same what I'll call "disappointment" in the perceptions or demands of the American consumer. I agree with that.

That being said, I think there are worthwhile exceptions. For example, Lord of the Rings. Even as a painfully long movie, the fact that they took the time and really did pretty good justice to that very sophisticated, deep, and meaningful story, I think it was appreciated by the general marketplace. It's just hard to do. And those are the exceptions.

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like