Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

From the ashes of the cancelled Hero project, Phosphor Games steps into the light in this new interview with Chip Sineni, the studio's head, in which he outlines the struggle to move beyond the fall of Midway and resurrect the concept as Awakened.

[From the ashes of the cancelled Hero project, Phosphor Games steps into the light in this new interview with Chip Sineni, the studio's head, in which he outlines the struggle to move beyond the fall of Midway and resurrect the concept as Awakened.]

The story's as old as the industry itself: A studio goes bankrupt, and works in progress are canned. But one Midway Chicago team felt they had something special in a game they called Hero, an open-world superhero console game that they believed offered an unprecedented degree of customization.

And when concept art first leaked to the consumer press, intrigued audience reactions suggested that the Midway team had, in fact, been onto something before their project was killed after two years in development.

This trailer, revealed for the first time to Gamasutra, shows how the exciting idea would have worked. Consumer weblog Kotaku also discovered evidence of Hero's existence, and at a glance audiences made comparisons to Sucker Punch's Infamous and Activision's Prototype.

But Hero's conception and development preceded both of those two -- and further, the team was gunning to create a title that truly let players create their own superhero, from appearance to abilities like flight, invisibility and firepower.

Now a new studio founded by the ex-Midway team, Phosphor Games, is hoping to revive the spirit of Hero with a new angle on the concept and, hopefully, with an interested publisher.

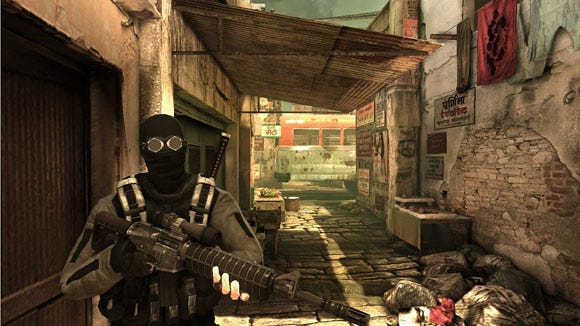

The spiritual successor of Hero is called Awakened (seen here). For the first time, Phosphor Games head Chip Sineni talks exclusively to Gamasutra about the project's story: from the last, anxious days at Midway through an undying passion for the game's concept to Awakened and beyond.

Let's go back to the very beginning, to Midway. Where did Hero come from?

Chip Sineni: First of all, the game started out in 2006 -- which was a long way back. Which was before Infamous, before Prototype, even before Crackdown. We were working on it for quite a while.

A lot of the genesis of it was, I think one of the designers was looking at [Cryptic Studios and NCSoft MMO] City of Heroes, and they thought it would be really neat to make... a high-end action adventure game for consoles.

It's even beyond superheroes. It's really letting players create the video game characters of their dreams -- to create something and actually play with it.

So you had a concept that you really loved, and you've said everyone who saw it was attracted to Hero and enthusiastic about it. I've been told it focus-tested higher than almost anything Midway's studios had produced in a decade. But then, the bankruptcy. What then?

CS: I think Midway, before there was a buyer involved, really wanted to see if they could make it out on their own, and literally canceled every game that wasn't Mortal Kombat at that point. It's kind of understandable that Mortal Kombat was more desirable to an investor than new IP that no one had heard of.

But all of us thought... we have to do something with this.

How many were on the project?

CS: We had a pretty small team. Unlike some of the other, bigger games at Midway, they kept us pretty lean. It was a huge open-world game, but we were under 30 people or so. that was like a ramp up... 15 people for most of us. Finally we stepped up to 30 and we were planning to move on.

What was it like then, to have poured so much energy into the project and yet receive the distinct sensation, once the storm hit, that you were running out of time and options to save it?

CS: I think working so long on it, too -- you know, having two years into it, it was a pretty big thing. The first thing we did is there was some writing on the wall that [Midway's collapse] was happening. It was all over the press that Midway would have to get sold, and there was so much tension there.

There was a publisher interested in seeing it... with a lot of ex-Midway people working there. So we did some massive, crazy crunch to get it in a showable state to get to this customer. For two whole weeks, people kind of lived there working on it.

And when we got back... they told us everyone was going to be let go.

After all that work that you guys had chosen to do, right?

CS: Yeah. It's not that Midway told people to crunch for two weeks. I think, actually, they discouraged it, they didn't want us to... I think we were just all so invested in trying to get this thing happening that people just put blinders on.

The whole studio was going in this chaos, and everyone was kind of focusing on what we could do to make it better. I think for the longest time everyone was in denial that Hero wouldn't get made, somehow.

They thought, "It can get picked up and we'll make it again." And after that point came the slow realization: "This is going to take a really long time."

What did it feel like?

CS: Everybody on our team was working as long as they could with all this chaos and looming doom. Other people in the studio probably thought, "You're idiots. This whole thing is going to collapse."

When Warner Bros. picked up Midway, it really only wanted the Mortal Kombat studio and back-burnered everything else, right? Were other teams fighting for consideration, and were you showing Hero around, trying to sell it off?

CS: Early on there was no known buyer for Midway. Lots of IP got shown to lots of publishers. All the IP was for sale. Eventually, my understanding is Warner Bros. bought most of it, but not all.

This was a huge shock to all of us -- besides losing your jobs, it is like a friend died. Many of us had two years of eating and sleeping this game. Not sure if it is hope or denial, but you really try hard to keep anything of a team together.

Right away, you start having "offline" communications with the whole team, with a team email distribution list through personal email instead of corporate, giving them updates on how you are still trying to sell this game that we all fell in love with, but it is really hard -- they all need jobs, many have families, they can't just hang out in limbo, waiting.

It is pretty crazy how even after getting let go... how much the whole team was still engaged and wanted to make this game more than anything. Looking back now, it is pretty amazing we have so many of the Hero team working with us now at Phosphor, even though it took us over a year after the layoff to get a physical studio.

Could you take any of it with you?

CS: What we're doing now is, I mean -- we just totally started over. We don't have any connection to the old codebase, story, assets, whatever. What we have is the very cool idea that create-a-player [concept of Hero's central feature] is this really awesome opportunity to change your character and your abilities to whatever you want them to be.

It's crazy, because after you have that power... you get so used to that idea that when you see other games, you're like, "I wish I could just do this or that, I wish I had this other kind of skill."

Do you think players generally are dissatisfied with pre-prescribed characters?

CS: Well... I worked on Psi-Ops and Stranglehold, and a lot of that... as cool as [Psi-Ops protagonist Nick Scryer's] abilities were, he looks almost generic. And even Stranglehold, where you're an older Asian man -- a lot of times, players don't interact with the game because they might look at the main character and say, "It's not my power fantasy to be this person."

With Awakened, we'll really let players make their own character.

When you let players have their own power fantasies, is it challenging to then balance the rest of the gameworld to make sure players still find it engaging? What's to stop people from just making some hugely powerful character who can easily surmount everything you design for them?

CS: It is really challenging. To some extent, you have to put limiters in. We have a point system in; we're constantly refining what we're letting people do. Maybe for the campaign mode, the first time you do it we want to make sure people are just having fun. Why not just let them do something and have fun with it?

Multiplayer has the whole competitive end, where you've crafted your characters and play them against others. In that case it becomes really about letting players make their own game up. If you want to have, say, like five people playing villains against policemen, or set it up so it's aliens versus marines -- just let them make their own game. We really don't want to constrict them.

Back to the last days of Midway: how'd you get from having a beloved project at a publisher in its last throes to forming a new studio with a new concept?

CS: Midway laid off most of the team at Christmastime [2008, just prior to filing for Chapter 11], and then there were a few of us still at Midway that were showing the game to people.

The reality was I was a project lead at Midway, and now there was one project [Mortal Kombat]. So... it was kind of inevitable, and people who weren't assigned to that project were just let go. During that whole time, the writing was pretty much on the wall. You get a couple days to figure out what your future's gonna be.

I'd had this long, slow five months of watching the company change. And I can kind of plan stuff, so at that point [my team] started really talking about forming a company.

So you founded Phosphor Games.

CS: It's funny, because I've been part of start-ups before, and I thought I kind of at least knew what a lot of it was. It's crazy if you're not... the founders of Infinity Ward or someone [with that profile]. For us, it was like "we haven't heard of your game that hasn't shipped yet."

I've been in the industry since '94. I have worked on a lot of games I could point to. But when we started it was a little weird, there were companies trying to buy Hero and use us as the developer. The engine and content did exist, and the company was selling it. But ultimately when all the finalization happened, you know, July or so, that window closed.

After that, we were trying to figure out what we could do, and we thought maybe it'd be easier to get something else going while we're trying to make this happen.

Did you start with some work-for-hire projects? That's not so unsusual for new studios.

CS: I had known Epic a little while -- Midway was one of the first adopters of Unreal Engine on a big scale, before everyone was using it for console games. Epic, even to this day, has been super supportive of us. They gave us, as a company, our first dollar; they paid us to do work, and we still have an amazing relationship with them. They're really quite a role model for independent developers.

What other kinds of work have you guys done?

CS: When they announced Kinect, we thought that even though the focus wasn't the hardcore market we were used to, we thought it was super cool and innovative. So we just kept knocking on doors, and then eventually we got to do some work on Kinect Adventures.

What'd you think of working with Kinect?

CS: Oh, it was very cool. I think it's just that it's a different audience than what other gamers are used to. If you read the hardcore press, they were not into our level, the "Space Pop" game. But then I'll talk to parents, and they'll tell me that it was a favorite.

They really don't have to care about something that's not for them. But I think getting everyone into games is a very cool thing... Anyone can have a fun interactive experience. I think there are a lot of really cool games you can make with Kinect that you probably couldn't make before.

It just takes time... to see what's profitable. The earlier stuff is more obvious, and then there will probably be some really cool things you can do with Kinect once it has enough saturation.

Now you've established Phosphor, and you'd worked on some outside projects...

CS: At that point, we started splitting development between our contract stuff and building our own engine. With our first engine... Hero was a big, open world game. I think it's kind of obvious that they are hard to make; I mean, we did have a PS3 open world game with everything working on disc for Hero, so it was hard but not that hard. What was harder was making the content compelling.

It's even harder when the player can do things like fly, for example... you design this super cool situation and [testers] just flew over it. Flying isn't really where most people are in their game space... Imagine in Resident Evil if the zombies came at you and you constantly just flew away.

Maybe it would be cool for 10 minutes but it's hard to sustain something like that. So when we were rebuilding the engine we really looked at... we always want there to be lots of different ways to play the game, but we didn't really want you to just leave situations. We have a more focused kind of gameplay environment now, more action and less open-world.

How does the tech you're building now compare to what you were using before?

CS: Midway actually had lots of "engines" -- they were all based on Unreal, but had different features to their core. For starting Hero, we had used the open world engine. After the first year of using it, though, it was clear that it was still rough and would need some time to be working well on console.

This engine was one of the first videos leaked; it shows off a driving feature that we never revisited. So after a year in development, we switched to the Stranglehold engine, which hadn't shipped when we started, but now was finished and working on the major consoles and PC.

So in six months, our tech team did a massive integration, and we added a open world streaming system, TNA's combat system, our own special ability system, [create-a-player's] front end and renderer, and miscellaneous stuff like rudimentary crowd system all to the Stranglehold engine.

We had literally just finished integrating all these systems, and finally got to play with all the pieces together when the project was terminated.

What lessons have you kept from Hero? Now that you've got to start again, how do you refine and ressurect the concept, and what kind of areas are defining to your team?

CS: Something we're still really interested in is the idea of a morally gray enemy. We're all fans of Hayao Miyazaki movies... where someone might seem like an enemy, but maybe they're not. Generic "mercenary force" villans aren't that compelling. So we're really wanting to find a way to make that more interesting.

And we really want to integrate a friendly group of people going through the adventure with you, which is a way to do storytelling.

Right now, we have a hard time with knowing whether the player character will have a voice or not... It's something we still debate inside a lot. If the character doesn't have a distinct voice and name, are people going to gravitate to him? We think as long as, no matter what, there's a really compelling story around them, and the character isn't being treated like they're a mute, they'll feel like that person's part of the world.

It seems early to be talking about the game. Are you further along than we might think?

CS: We totally weren't planning on talking about it until... this weird disinformation started popping up on the internet. It's really, really early. We're talking to numerous publishers on it. We've had a lot of back-and-forth.

But for right now... the vision we most want first, before we get too serious [with a publisher]. We have other projects in the queue, so we're able to do that right now. Phosphor -- we're like 17, 18 people or so [on the project team; studio team is about 27 internally], plus Chicago is cool that there's a whole network of contractors, people you've worked with that are all freelance now, and stuff like that.

The Prototype and Infamous comparisons... do you think that makes it easier or harder to for people to get behind what you're doing?

CS: I think it's a little easier and a little harder. The harder thing is that those two games are very much about a specific character who's this modern superhero in an open world. And now we're really trying to... we're far closer to Gears, Resident Evil, Uncharted kind of space, with hopefully really interesting situations -- but with your own character.

We're really just trying to let players create their own kind of person. In that kind of way, those games -- we keep getting compared to them and we're actually pretty different. How powerful create-a-player is, is really the coolest feature about the whole game. It's really hard to show that in a way that isn't flipping through a lot of menus.

How does it feel now to be on your own with Awakened?

CS: It feels really good. It's neat being independent and forging your own path -- I was at Midway for 10 years. There are a lot of dangers with being independent, too -- it's just really neat knowing we're going to do the things that we set out to do. It's just the right thing to do at this point and it's pretty clear.

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like