Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Talking to game PR professionals at Electronic Arts, THQ, Telltale, and Destineer, Gamasutra looks at how carefully released information builds interest in today's games, exploring the tricky job of post-Internet public relations.

[Talking to game PR professionals at Electronic Arts, Telltale, and Destineer, Gamasutra looks at how carefully released information builds interest in today's games, exploring the tricky job of post-Internet public relations.]

Magical thinking is a common phenomenon in the world of video games. Treasure chests appear at dead ends, miraculously holding an item that allows the player to get out of a dungeon. Non-playable characters are trapped in looping animations until asked for their stories. Rocket launchers are lovingly placed right before the boss encounter. To the average fan, this is just good game design.

In the real world, magical thinking is an indicator of mental illness. Of all the things that could explain how and why something has happened, our individual existence is usually among the least relevant. We are beside the point.

The practice of public relations for video games is an extension of the art of game design. Using abstract language and insinuation, PR sells audiences on the existence of a world hand-crafted to respond to their interactive needs.

Gamers are always eager to discover the secret megaton waiting to be unleashed at an E3 press conference, or leaked to YouTube by some European enthusiasts. Gamers may be quick to forget about today's games, but they are always ready to fan the flames of excitement about what might be coming tomorrow.

What follows is a survey of how PR is contributing to the current landscape of game development. How can the power of PR be used to successfully sell a game? What happens when PR sells a game that's different from the one developers were intending to make? What happens when the secrets turn into giant anticlimaxes? How is the advent of downloadable content and the notion of the evergreen title changing game promotion?

Before a publisher can sell something, they first have to define what it is they're selling. "The most important thing to consider when planning a PR campaign is the game itself," says Tammy Schachter, senior director of PR for EA's Games Label. "Long before the game is even playable, we work together to find the language that properly communicates the features of the game and build a timeline that maps to their development schedule."

Establishing a schedule to release information at a pace that gradually builds anticipation until the climactic release date is crucial to this process. "We want to get a very high awareness and purchase intent on our games for the ship day," says Jerome Benzadon, global media relations manager at THQ. "To achieve that you have different strategies but of course you have to think about when to communicate what on the game, where and how."

With an established identity for a game internally, publishers can focus on specific demographics to which the game will most strongly appeal, and then create a message that caters to them. "For a game like Wallace & Gromit's Grand Adventures, we need to reach out to the fans of the Aardman films in a different way than we would reach out to hardcore Xbox gamers," says Emily Morganti, former PR director for Telltale Games. "Since Telltale does episodic releases, we have to commit to spending the next six months or so communicating with those groups on a regular monthly basis."

Creating appropriate messaging to target different groups is a matter of subtlety. During the launch of the original Gears of War, Microsoft hired David Fincher to cut a moody television commercial set to Gary Jules' atmospheric cover of "Mad World", which originally appeared on the Donnie Darko soundtrack.

In contrast to the trailers released directly to enthusiast gaming sites, which emphasized combat intensity, Microsoft wooed mainstream gamers with apocalyptic mood and the simple strength of Gear's distinctive art style. It also associated the apocalyptic fantasy with the emotionally wrought overtones of Richard Kelly's cult classic film, creating a sense of implicit credibility.

Nintendo also used a Hollywood crossover and ambient suggestion during the launch of its Wii console in 2006. Traffic scribe Stephen Gaghan was hired to direct a series of pithy spots that played on Nintendo's identity as a Japanese company. Two Japanese businessmen were shown driving around the country in a smart car giving hands-on demos of Wii Sports.

Nintendo also used a Hollywood crossover and ambient suggestion during the launch of its Wii console in 2006. Traffic scribe Stephen Gaghan was hired to direct a series of pithy spots that played on Nintendo's identity as a Japanese company. Two Japanese businessmen were shown driving around the country in a smart car giving hands-on demos of Wii Sports.

Gameplay footage appeared in brief glimpses and was de-emphasized in favor of reaction shots and warm pastels that sold the console as an inviting social encounter with something modern and vaguely Asian. This was a clever nod to the stereotyped xenophobia that many mainstream consumers held against the very foreign world of video games.

In the case of House of the Dead: Overkill, Sega relied heavily on an association between their light gun shooter and the Tarantino-Rodriguez mash-up Grindhouse. All the game's trailers and commercials were intercut with video footage mimicking the '70s exploitation horror of that film to contextualize the otherwise familiar gameplay scenarios of zombies lumbering towards the player. While the core gameplay was traditional and easily recognizable, Sega went out of its way to brand the game with a cultural association what was timely and fashionable.

House of the Dead: Overkill may have had distinctive and entertaining trailers, but it still sold poorly at launch and was quickly discounted at retail. The game was reviewed well across the board, and was released in February on a platform with little direct competition for violent shooters. So what happened?

"Casual gamers make their purchase decisions on a completely different set of criteria than core gamers," says Jeremy Zoss, communications manager for Destineer. "You won't reach the right audience by treating a casual game like it's a core gamer product."

Nintendo platforms, in particular, have been tricky for third-party publishers to navigate in recent years. Both Wii and DS dominate global hardware sales, but the review-driven core gamer style of titles that often sell best on PlayStation 3 and Xbox 360 struggle to sell through on Nintendo consoles.

"The tone is really important. With the hardcore gamer, you want to convince them that they are going to see something that they've never seen before, or if they have seen it before it was something they loved," says Sheila Bryson, director for Spark PR, and an industry veteran. "With casual gamers you want to create messaging that conveys the experience of the game, and how much fun they will have playing it."

"We do have studies showing how people heard about our games and how much the score is important. The score is very important for a core game and less for a casual game." says Benzadon. "When a reporter says that the game is good, the game is good; when an ad says that the game is good... you are not sure about it."

In some cases, games can perform well enough in the marketplace but still garner a reputation for having underperformed. Media Molecule's LittleBigPlanet was given a major announcement during Phil Harrison's GDC keynote in 2007, more than two years before it was released. Its debut was longer than God of War 3's at E3 2008.

In terms of emphasis and messaging, it was positioned as a tentpole game. When its opening month sales in North America were 215,000 units, many in the industry were disappointed.

Sony had put what was meant to be a casually enjoyable, mainstream title on a PR schedule for an epic akin to Halo 3 or The Legend of Zelda: Twilight Princess. Even after a strong E3 showing, the company struggled to maintain the popular momentum it had surrounding the game's original announcement, in part because of the long lead-in time.

"You always want to have as much time as possible, but often a long campaign just doesn't make sense for a smaller game," says Zoss. "While I see a lot of year-long campaigns for blockbuster games, casual games typically have shorter campaigns. We often announce games six or eight months before release, but sometimes it can be less than that."

The moment of the reveal is as powerful in the world of PR. Seeing a favorite game unveiled is a literal dream-come-true for many game fans; from Miyamoto's 2004 Zelda reveal, to Activision's Call of Duty: Modern Warfare debut during the 2007 NFL Draft. "With a AAA title developed by a well-known studio you want to start building anticipation early," says Bryson. "Which is why you see a lot of big games being announced sometimes more than a year in advance at E3."

"If you are working with a studio that people are already in love with, then you can start talking about a secret project and generate a lot of interest with everyone from the NeoGAFers to mainstream media like USA Today."

One of the most notorious examples of a hotly anticipated core announcement is a Kid Icarus title for Wii. Nintendo fans have been anxious for the NES title to be reborn for years. In a 2005 interview with IGN, Shigeru Miymamoto made an offhand comment that the Eggplant Wizard would be "coming back."

Two years later, Kombo broke a story that Factor 5 was developing a Kid Icarus title for Wii and published a plethora of alleged concept art. In the months leading up to E3 2008, IGN confirmed that a Kid Icarus game was in development and would likely be at E3 in its Nintendo Voice Chat podcast series. E3 came and went and there was no such announcement.

In the fall, rumors began circulating that Factor 5 was in financial trouble and it was revealed that they had shut their doors (and now several ex-employees are suing the company for back-pay). Enthusiast fans belief in a Kid Icarus title's existence was so strong they inspired an opportunistic developer to attempt to sell Nintendo on the idea.

News of the project leaked to the gaming press, and suddenly gamers were sure there was irrefutable evidence that one of Nintendo's hotly guarded secrets had been revealed -- even before Nintendo had actually greenlit anything.

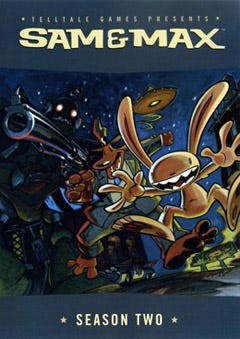

Conversely, Telltale Games experienced an instance of fan interest being so high that it predicted a real game's existence. "Back before the first Sam & Max episodes even launched on PC, we had people writing to us asking us to bring Sam & Max to the Wii," says Morganti. "A comment I made on our company blog sort of snowballed into a big internet rumor that kept resurfacing for a year and a half."

Once a game in a popular franchise is announced, the management of expectations and dissemination of information becomes just as important as the announcement itself. "In general secrets and exclusives are very important, but that's a strategy that works much better for core games than casual games," says Zoss. "Core gamers typically have to make tougher purchase decisions, so a steady stream of information keeps them engaged with a product."

Alternately, many publishers commit to annual updates of top-selling franchises and must create new ways to frame those iterations as megatons each year. "We're always looking for the "big idea" that is going to help the game break through the noise and get gamers and press to take notice," said Schachter. After years of pitching the Need for Speed series as an approachable arcade-style racing game, EA wanted to pitch Need for Speed: Shift as a more realistic experience.

"To give the press a glimpse of what it feels like to be behind the wheel of a real race car, we chose to announce the game at a real life race track in Sweden," says Schachter. "This setting was especially appropriate since the senior developers on the Shift team are also real life race car drivers. They were on hand to race the press on the track and then demo the game, showing just how the visceral experience in the game delivers a true driver's experience."

Ultimately, stoking hardcore enthusiasm with teases and secrets can be a dangerous game. "The effectiveness of a 'secret strategy' really depends on the assets that you have," says Bryson. "At the end of the day, PR strategists need to understand the market well enough to be smart about what titles merit that much advance hype, because our own reputation is at stake as much as the reputation of company we represent."

As the window for promoting games in advance of their release is shrinking, possibilities for promoting games after launch are growing. "Episodic content and/or DLC gives games PR longevity. Multiple media touch points are always a good thing, and most gaming sites will cover a new piece of DLC," says Bryson. "This is your opportunity to get the, 'Oh man, I meant to pick that up... now there's even more cool new content... this is going to be money well spent,' reaction."

Telltale Games has built an entire business model around episodic gaming, banking on the multiple windows to promote new content it offers. To compensate for the extended promotion of a series after its first episode is released, they try to announce games as closely to release as possible.

"Since our games are downloadable and release frequently, the closer we can put the announcement to the instant gratification of getting the game, the better," says Morganti. "We'll be in the news for the five or six months that the series is releasing; to also be in the news for six months before this ramping up to the series would be overkill, and hard to pull off."

Deciding how and when to promote a game after its initial release can be difficult, and committing production resources to making downloadable content before a game has been released is a strategy that requires significant investment. Sometimes choosing a license or mainstream-friendly genre can help make PR still feel fresh long after a game has released

"Destineer has released several games with a built-in audience. For example, Iron Chef: Supreme Cuisine was covered heavily by foodie blogs, sites and magazines," says Zoss. That audience is much less likely to be interested in daily gaming news and updates, so while they might have missed the initial wave of publicity, there could still be worthwhile sales generated by a continuing promotional campaign.

"We make our post-launch ad spending decisions the same way Nintendo does: by analyzing the situation to see if it makes sense," says Zoss. "We have from time to time decided to spend money on an already-released game to keep its sales momentum going, and we make those decisions on a case-by-case basis."

Nintendo has an established history of supporting evergreen games that can sustain strong sales over an entire year, or longer. Games like Nintendogs, Mario Kart DS, Wii Fit, and New Super Mario Bros. benefit from recurring media buys -- in some cases, years after their initial release. Sony similarly promoted the original Resistance with a new round of print advertisements during the holiday 2007 season, a full year after the game's release.

Episodic games naturally dovetail into this kind of long-term promotional plan as it provides opportunity for repackaging older content into "boxed" sets with bonus features.

Episodic games naturally dovetail into this kind of long-term promotional plan as it provides opportunity for repackaging older content into "boxed" sets with bonus features.

"When we bring a game to retail, we're not trying to reach the same people we've been reaching for the past six months with the downloadable releases," says Morganti.

"Maybe you didn't want to play Sam & Max when it was released as monthly downloads, but now that you can get it on a DVD with a cover painted by Steve Purcell, and audio commentary with the design team, and an outtake reel, you're sold. And since we come out with seasons of games, like a TV series, every time we launch a new season, interest in the old seasons is renewed."

"Game PR is really unique," says Bryson. "With the majority of product launches outside of the gaming industry, you want to have a big media blitz at the time of availability. You don't want to build a long buzz because eventually the buzz will turn into oversaturation and consumers will lose interest."

The video game fan has, traditionally, been a separate class of consumer. He has had a voracious and participatory appetite for every last detail of his most anticipated games. Historically, game PR was less about selling gamers and more about acting as gatekeepers to information.

Core gamers know there is something great and exciting lurking behind closed doors at the office parks around the world where games are made. PR became an act of providing spurts of information to keep the core gamer's imagination engaged in just how an upcoming title would appeal their wants and needs. "Joe Gamer wants to see every screen they can of Uncharted 2: Among Thieves, but Joe Consumer doesn't want to see a photo of every component in a GPS device," says Bryson.

Increasingly, Joe Consumer is becoming Joe Gamer. As game budgets continue to rise while the Wii and DS dominate marketshare, it is unavoidable that someday very soon, game PR will have to focus more on the mainstream person than the core gamer.

Convincing people that video games deserve to be a part of their daily entertainment schedules will require more than magical thinking. Like Nintendo's gamble with motion controls in 2006, it will require meticulous market research, a vision for the future, and a terrifyingly expensive leap of faith. There's nothing magical about it.

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like