Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

In this postmortem of Tale Of Tales' thought-provoking art game The Graveyard, the creators detail what went right and wrong, revealing funding wins, download statistics, and more.

[In this postmortem of Tale Of Tales' thought-provoking art-game The Graveyard -- which is free to download in a basic version for PC and Mac -- the creators detail what went right and wrong, revealing funding wins, download statistics, and more.]

History

Your avatar is an old lady who walks through a peaceful graveyard (soundscape à la Endless Forest). That's it. That's the core game design.

The above was the initial concept of The Graveyard. At that point we also considered adding some gameplay to "make this more poignant and to give people something to do". We were thinking of a game where you would try to find the answer as to where the husband of the protagonist was buried. And every time you play, it would be a different grave. When you find the grave, the lady would do something (smile, cry, talk, etc.) -- a different thing every time.

After coming up with this idea, we realized why we thought it was strong. Like The Endless Forest, The Graveyard was designed around a core activity of walking through a certain environment. This simple activity is made meaningful by defining the avatar and the environment. A deer in a forest. An old lady in a graveyard. Both immediately imply meaning.

This happened on 24 September 2005, two weeks after the launch of the very first phase of The Endless Forest. We keep track of these things in a wiki. A year and a half later, on 29 May 2007, we added a note:

Does the gameplay described in the original version really add to the emotional impact of the game? Doesn't it, on the contrary, reduce the impact: perhaps giving players something to do, creates a layer of protection against the emotional impact?

This happened two weeks after finishing the first prototype of The Path, which lead to the decision to remove all buttons from the game's interface and with them much of the player's control over the avatar. For the same reason: the gameplay distracts from the story.

So the concept was revised:

A graveyard. You steer an avatar representing an old lady. You move her around but she walks very slowly. The camera is fixed to the avatar. No rotating, no zooming (re-enforcing the feeling of limited motion of an old body).

You walk through the graveyard. The camera follows you.

All the other aspects of the game were described at that point as well. The sound design, sitting on a bench listening to a song, quitting the game by walking out of the cemetery and even the idea of the lady's death and charging for that feature. There were some additional thoughts that were omitted from the final version: text on the tomb stones and feeding birds. We also considered making several chapters in which something different happens on the bench every time. And charge a very small price for each. We still like that idea.

Early concept sketch

Theory

When we talk about "story" with respect to our games, we don't mean linear plot-based narrative constructions. When we say story, we refer to the meanings of the game, the content, its theme. We believe that expression in any mature art form is driven by this content, by the story. In computer games, however, the reverse is often true: stories are chosen because they mesh well with a certain game structure or mechanic. Since games are about winning, they tend to feature stories about heroism and good versus evil. And even those stories are forced to fit the tight corset of game rules.

We are personally not very fond of war stories and the like. But we do believe that the interactive medium can be used for many things other than games. So we try to develop forms of interaction that express different kinds of stories.

We don't mind calling our work games because we believe that contemporary computer games have already crossed the borders of traditional games. Most of them just don't realize it yet. They don't realize that the most interesting aspect of their design is the way in which they express the story: through the environment, the animations, the color, the lighting, etc.

All those things that contribute to immersing the player in a virtual experience. Compared to this amazing new quality, ancient game structures seem rigid and out of place. But we feel that the commercial success of the games industry is holding the medium back from evolving into a true artistic medium. Most of any modern game budget is spent on the elements that express the story, on the simulation.

But very few developers are willing to publish the product without the game structure that they are so accustomed to (and for which they know there is an audience). As much as the game structure protects the player from experiencing the story, does it constrain developers within the confines of triviality, of toys?

With Tale of Tales, we try to develop a new form of interactive entertainment. One that exploits the medium's capacity of immersion and simulation to tell its story. This is why we made the gesture of charging a symbolic amount of money for one extra feature: the death of the protagonist. That small change alters the experience greatly. We wanted to make the point that it is the experience that matters, not the length of the game or the number of levels or enemies or weapons, etcetera.

It is probably safe to say that our work, and especially The Graveyard, focuses on the experience of being more than on seeing. Everything that you do in the game is there because we think it helps you experience the situation. We offer the player an opportunity to play their part in a narrative. Perhaps the request to "play a part" replaces "playing a game", and perhaps the performance we expect of the user is a theatrical one, not one based on a sportive challenge.

Of course there was also some irony involved in choosing the traditional trial/full version format. Especially considering the fact that The Graveyard parodies or criticizes certain well-established game concepts. In many games, death is simply a temporary game state, a way for the game to express your failure.

We were motivated by this shocking disregard for the meaning of death to make something that explores this concept more deeply. Not just your own death but also how we live our lives among people who will die or have died. Death is a fascinating part of life. We find exploring the emotions and contradictions triggered by it interesting and moving.

Finding funding

The very same night of the concept revision, we started working on the dossier that we would submit to the Flanders Audiovisual Fund (or "VAF", in Dutch) to request funding to build The Graveyard. Unlike some other independent game developers and artists we don't have a "day job". Making games is a fulltime occupation for us, simply because the things we want to make are incredibly time-consuming. So we need funding to work on our projects. A large chunk of the money tends to go to our wages.

The request was submitted on 4 June 2007. Submitting funding requests was nothing new for us. When we realized that getting funding was more a matter of luck than anything else, we made a point of submitting a request for funding with every deadline, which was every three months. We have a long list of ideas, so there's always something to submit. And sometimes we get lucky. We had already learned that smaller projects with lower budgets make a better chance at being accepted. So we chose The Graveyard this time.

The Flanders Audiovisual Fund focuses mainly on film. It is a vital instrument in the local creation of cinema because without government support it would be impossible to create Flemish films, given that the territory is so tiny and film production so expensive. Yet cinema is an extremely popular form of entertainment, here also. The support of the Flanders Audiovisual Fund offers a guarantee that we don't get flooded by alien culture. I like to think that games fall into this category too.

Sadly, the Flanders Audiovisual Fund does not agree, yet. So we generally have to submit our requests for funding in their "Experimental Media" category, which mostly exists for video art and museum-type media art, a category with a much smaller budget than film.

On 11 September 2007, we received the good news that the Flanders Audiovisual Fund had accepted our proposal. They were going to grant us 15,000 Euros (out of a total budget of 18,000) for producing The Graveyard. We needed this amount for two months of full time work for two people (plus the company overhead) and hiring a few freelancers for specific tasks.

We received commentary from the commission that makes the decision about a request for funding. A few things stood out in their assessment of The Graveyard. First, the good news:

Some members of the commission stress the artistic and graphic qualities of Tale of Tales. Through previous works, they have proven to be capable of creating a fascinating universe. The commission recognizes the special position of Tale of Tales within the international games landscape. One member stresses the diversity in the work of Tale of Tales, with big projects like The Endless Forest and small and focused ones like The Graveyard.

But despite of the final positive response of the commission, there was still a fair bit of criticism.

The commission is divided about the concept and execution of the project. Most members are convinced by the simple, humoristic and clever concept. The idea of exploring the theme of dying in an interactive digital piece is relevant and intriguing. Tale of Tales deconstructs the medium of games. Other members believe that the project doesn't offer much artistic added value or content and is only based on a superficial experience of shock.

One member considers the project to be more of a parody on Tale of Tales' own work than on the games industry or game aesthetics. The members of the commission also differ in opinion about the public reception of the piece. Part of the commission is afraid that the discrepancy between concept and experience will be too great, causing frustration with the players.

And the eternal fantasy that art people have about digital projects:

One member of the commission thinks that the project can also be realised without the support of VAF.

This always comes up. Because we make games and because we insist on distributing them digitally rather than rarifying them on media art festivals or in galleries or museums, some people think that our work can support itself. We hope some of it will be able to in the future. But as you will see in the final chapter of this article, about sales and response, The Graveyard is not one of those projects.

Pre-production interactive prototype to get a general idea of the gameplay and explain the concept to our collaborators

Choosing Technology and learning how to use it

We had made a very simple blocky prototype of the game in Quest3D, the authoring application we use for making The Endless Forest and The Path. But since The Graveyard was such a small project and very simple in terms of technology, we decided to take the opportunity to experiment with a new technology. We had already been looking at Unity in the past but it wasn't until we heard that it also supports development for Wii that we got really interested. So we wanted to try it out, to see what we could do with it.

Experimenting with new technology also fit within the research into different types of programming that we are doing with media arts collective Foam in Brussels. The best way to find out the advantages and disadvantages of an authoring tool is to develop a real project with it from concept to publication.

An extra motivation was the satisfaction of a long-term curiosity: would there be an audience on the Mac OS platform for our work? We had always suspected that there was one but had never been able to test it (because Quest3D is exclusively Windows-based). You will find out in the final chapter of this article how that turned out.

While games made with Unity can be run on several platforms, the authoring application only runs on Mac OS. Auriea had been a Mac user since forever. But Michaël had always been using Windows. Working with realtime 3D and Quest3D had moved our activity in the direction of Windows, so the prospect of doing a Mac project was exciting for Auriea.

We knew from the start that programming in Unity would not be a lot of fun for us. Because it is script-based and we are used to the visual programming in Quest3D. But literally everything else in Unity came as a welcome surprise. As opposed to Quest3D, Unity is designed for making games. This means that a lot of things you would have to build for yourself in Quest3D are a standard component of Unity.

At first, this felt a little bit limiting and even patronizing, but as we realized that we were in fact making a game that wasn't that much different from other games, we welcomed the convenience. Also, as opposed to Quest3D, Unity has been designed. Designed with the user in mind. Unity is not just an interface to a bunch of technical features, which is what Quest3D often feels like. Unity is an authoring application for humans to get stuff done.

The most delightful aspect of this well-thought-out design is probably the asset managment (which is nothing but headaches in Quest3D). Unity does not use the concept of importing assets. Instead you put all your models and sounds and textures and scripts in your project folder and the editor finds them for you. Every time these assets change, they are automatically updated in the game.

This is especially nice for Blender files, which are supported directly by Unity. You can easily switch between Blender and Unity and make changes. It's a fluid process. The same is true for scripting. Even its Collada support (which we needed to get our character animations out of Max) is excellent. We could probably have shared the project folder between the two of us, but our network tends to be a bit flaky for Macs, and we like to keep a repository of our projects.

So we decided to use Unity's Asset Server technology to share the project. It's a very nice repository system built into the application. Sometimes an update requires a restart of the editor, but even that isn't very problematic as Unity keeps a cache of your project that allows it to load things in the blink of an eye.

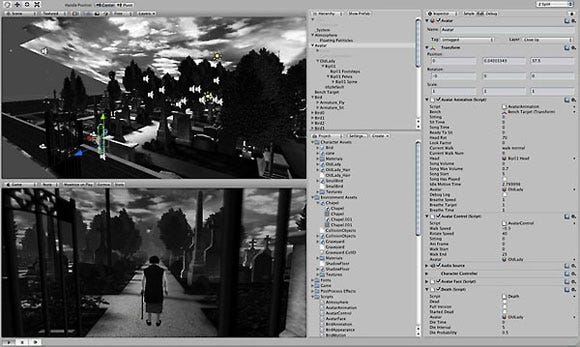

The final game as it is displayed in authoring application Unity

At the top left, a schematic view that allows you to see your game world from any angle, even when it is running. Underneath that, the game as it is seen by the player. In the middle, the bottom window is basically an overview of your asset folder and the top window shows the assets that are actually used in the game. To the right, you see the exposed properties of the selected game object, in this case the avatar. You can change these properties while the game is running, which is very handy for experimenting.

We will only ever be able to create simple applications with Unity because of its script-based programming, which is often too much to wrap our art-heads around (even though, in and of itself, Unity's implementation of Javascript is very neat and usable). So Quest3D will remain our tool of choice for anything that is a more sophisticated. But for all the other things, simpler games like The Graveyard, Unity's cross-platform delivery and asset management, is very very seductive.

What went right and what went wrong

Because of our unfamiliarity with Unity, production of The Graveyard took a bit longer than it could have. We started prototyping and experimenting in the trial version of Unity in December 2007 but the game production proper started in January 2008. It had to be interrupted in February during the Game Developers Conference because The Path was selected for the Independent Games Festival.

Making a suitable demo and video clip together with the trip took about a month. And after that -- like so many other GDC visitors -- we were sick for a week. So, in total, production of The Graveyard took between two and three months for two fulltime developers and three freelancers: character animations by Laura Raines Smith, sound efffects by Kris Force and music by Gerry De Mol (each of whom will be featured later in this article).

The first thing we did was visit the cemetery of a small town in Belgium, where Michaël grew up. He used to like visiting this place. To get a feel of the kind of atmosphere we were going for, we drove over one day. Michaël still remembered how to get there. The cemetery of Izegem is a very peaceful and quiet place. There's nothing sad or sinister about it. And there's a certain harmony of human death and natural life that is very poetic. The layout of the Izegem cemetery seems to mimic the layout of a city: streets lined with grave next to grave, families buried close to each other and tombstones that look like little buildings.

The cemetery of Izegem, Belgium, served as the main inspiration for the environment of The Graveyard. Perhaps we have made a new kind of landscape painting?

We made a single concept sketch for the environment, just to capture the mood. And then we did a lot of research into pictures of old people. It took a while before we decided on the type of person she would be, how old exactly, which class, which ethnicity, etc. We wanted her to use a cane but she shouldn't be handicapped. Etcetera.

Michaël's grandmother of 98, who talks about death every time we meet her, obviously influenced some of the design decisions. But the avatar needed to be more of an archetype than an actual person -- so that the player can project their own experiences into the game.

From the start we knew we wanted to ask Gerry De Mol to make a song for the game. We had worked with him before on The Endless Forest, for which he made all the music. His music is often based on traditional folk music from all over the world and his lyrics are always very subtle and understated. He is one of very few artists who has the courage to sing about ordinary life and help us see the poetry in it. We knew that he could really express the right mood for The Graveyard. And we had wanted to use the Flemish language in a game for a long time.

We showed him our blocky prototype and the pictures of Izegem and explained what we wanted. It's always a bit tricky to commission another artist. Ideally you want an artist to make whatever comes natural to them. That's how they make their best work.

So when you ask them to do something specific, you limit them in a way. This may be the reason why the first arrangement of the song that Gerry made was not suitable for the game. It was much more dark and somber than the version we ended up with. We didn't want this game to be only sad. We wanted to have a broad mix of emotions. So we asked Gerry to lighten up the song.

For the animations, we also worked with a long time collaborator: Laura Raines Smith. Years ago, after a lot of trouble finding somebody who can animate characters in a style that we like, we haven't worked with anybody else yet. She made the animations for 8, for The Endless Forest, Drama Princess, is working on The Path and of course did the animations of the old lady in The Graveyard.

Our games don't have words in them. Or hardly. And there's no clear storyline because we want people to fantasize. So the animations are very important to express the personality of the characters and their mood. Laura excels in making animations that do this. She always adds those little things that make you feel for the characters. Animation is a form of artistic expression to her, not simply a way to make characters do things.

For The Graveyard, she started by sending us lots of motion capture files of old and sick people. But most of them were too exaggerated. We also doubted for a long time about whether the character should limp or not. And if so, how. Turning the character around is very slow. We wanted it to feel really hard to do, even if that doesn't make sense, realistically.

For the sound, we originally wanted to work with the person who did the sounds for The Endless Forest. But he was difficult to reach, so we asked Kris Force, who is assisting Jarboe with the music for The Path. As it turned out, she is an excellent sound designer and engineer and delivered lots of interesting assets.

The most important aspect of the sound design is that there is a gradual shift between coming from the outside, with its noisy city sounds, to moving towards the center of the cemetery, which is silent and warm. We still wanted the city to be audible in the distance, because this situation should not be isolated. That's why you hear the dog and the sirens and the clock tower (which chimes on the hour).

The interaction in the game was developed simultaneously with the assets. We had already created graves and tomb stones for both The Endless Forest and The Path, so we reused those in a different layout. The birds also came from The Endless Forest (even their behaviour algorithm is the same, though it had to be re-coded in Javascript). We started with nature sounds from The Endless Forest, as well, but these were replaced by more suitable mixes provided by Kris.

We always try to build a working version of the game as soon as possible. Even if it looks and sounds terrible, being able to get an early feel for the interaction is vital to development. We prefer to design as much as possible in the game engine, rather than on paper.

In the beginning, The Graveyard was in color. But when we were playing with post-process shaders in Unity (we really like post-processing images in real time! :) ), we fell in love with the black and white style. Probably because of watching too many Godard and Bergman movies...

The Graveyard is a simple project with very few features. But it was still hard to get everything done in time (i.e. before we ran out of money). A lot of elements, especially in the programming, are a lot more simplistic than we might prefer. And there were several elements that we would have liked to add. But we're used to finishing projects with long lists of features that were not implemented.

Our growing To Do lists contain everything we would like to see in the game, but the items on them get prioritized and reprioritized as the project continues. We work our way down the list. But there's always a large amount of features that remain theory. It's not always a choice of what would be the nicest thing for the game, but often a question of whether we can get it done on time and whether it delivers sufficient impact compared to the effort to create it.

Aesthetically, we find it very important that our games feel real. But they don't necessarily need to look real. We're more interested in finding a painterly style that is true to the medium, than a realistic or cartoony style that borrows from cinema. And while we like working with the realtime three-dimensionality of a game world, we are also acutely aware of the fact that the result is always a two dimensional picture. That's why we are more inspired by paintings than by the laws of physics. It's about creating an effect, not about whether or not it's realistic.

Lighting is very important, for instance. But we tend to use very few actual lights in our games: one or two directional lights, some ambient light. The rest is all about messing with the colors of the 3D objects and the color and density of fog. These are very dynamic in our games. That's how we get the effect of clouds passing in front of the sun, for instance. It doesn't matter that the black spots on the floor don't correspond with the shapes of the clouds. As long as it feels right, so right that you don't really notice it. It's not so much about creating a picture to be scrutinized, as it is about creating a mood that you can believe in, spontaneously.

The game was finished on time to be released on Good Friday, which is the Catholic commemoration of the death of Jesus Christ (we like playing with religious traditions). Before we released it, however, we sent it around to a few friends, to ask for opinions. The response was mixed, to say the least. The biggest problem seemed to be that the people we asked didn't appreciate the fact that the game only generated questions and did not supply any answers. They seemed to think of art as a kind of riddle that they needed to solve. But we only asked people who are used to playing games. More about the response to the game in the final chapter of this article, though.

Now it's time for the traditional overview of what went right and what went wrong in this project -- starting with the good news.

Getting funding

We know that there's a tendency in the independent game developer community to think that making games costs no money. But this only applies to people who make games in their spare time or who are supported by their families. We don't have any spare time, simply because we choose to make games that require a lot of work. And we do have families, but we're the ones supporting them, not the other way around. So we need funding to be able to do our work.

We had received support from the Flanders Audiovisual Fund before. So we knew how and when to submit proposals. And we had a good idea of the kinds of things they like. Our own focus tends to be on simply building a living and breathing world that feels nice. But there's very little understanding for this type of work in funding organizations.

We tend to be most successful when the cost of the project is low and the concept includes a little twist, a bit of irony, a tongue-in-cheek gesture. We often kid that we are doing these enormous amounts of hard work but we're only getting funding for telling a clever joke.

In The Graveyard, the twist was the added death feature in the full version and the fact that when the protagonist dies, she is still dead when you restart the game (in fact, we originally intended the game to require a re-install when that happened, but that didn't work on Mac OS which doesn't really use installers anymore). That added a kind of meta-narrative to the game that the people who decide on the funding seem to need.

It takes about a week to write and submit a proposal, so it's not trivial. But in the end we did get the funding quite easily, even if it was only a small amount of money. We actually liked that fact, because it forced us to keep the scale of the project small (after all we were still in the middle of the production of The Path).

Cover image of the project proposal: a simple outline of the entire game. We used the game's simplicity of design as a provocation

Great collaborators

Not to be underestimated are the contributions of Laura Raines Smith, Gerry De Mol and Kris Force. We were able to just throw ideas at them and they would come up with a creative solution and beautiful assets. Without requiring any real management. We are not very authoritarian. We like it when people work independently and take initiative. But that only works if those people spontaneously produce work that fits with the project. We were very fortunate.

Exploring game design concepts

The Graveyard is the realization of a dream, in a way. We had been discussing and blogging about games without rules, games without goals, games that are about being rather than seeing. But we hadn't really finished a game design that explored this thoroughly. The Graveyard gave us an opportunity to do so and to understand the advantages and disadvantages of such an approach. Not only in terms of game design as an art form, but also in terms of reception by the public.

Response

We were amazed by the response we got to The Graveyard, from the press as well as the audience. There will be details in the last chapter of this article, but we can already say that we are more than happy with the attention that the game received.

A lot of people really liked the experience. And many of those who weren't entirely convinced appreciated our efforts and expressed hope for the future. We got a lot less negative response to The Graveyard than we did to, say, The Endless Forest. I guess perhaps the hardcore gamers (who are very adamant about "criticizing" The Endless Forest), just shrugged and went elsewhere this time.

Demonstration leading up to The Path

Part of why The Graveyard was received so well is probably that we have been slowly but surely building a reputation for ourselves. The selection of The Path in the IGF and the double spread about the game in Edge magazine probably helped people to take our work a bit more seriously.

In a way, The Graveyard served as a sort of teaser for what people can expect from The Path. It deals with a similar theme and has a similar graphic style and gameplay. We also used it in this way, to get an idea of how people respond to this kind of concept, in the safe environment of an art project. Because when we release The Path, we will need people to be interested enough to buy it (or we face bankruptcy).

Selling a product

We did not sell enormous amounts of the full version of the game (details in the last chapter). But it was the first game we had released commercially.

We always like to receive emails from people who appreciate our work. But the silent flow of confirmations of purchase coming from PayPal was heartwarming in an unexpected way. Five dollars is not a lot of money. Nobody who owns a computer with internet access doesn't have five dollars to spare. But for people to actually spend that money on a downloadable bit of software is still not something that is as common as spending the same amount or more on a candy bar, cab fare, or a newspaper.

While we were setting up the whole thing for allowing people to pay with PayPal through Payloadz, we hadn't anticipated the emotional effect of people actually purchasing what we had made. Expressing their appreciation without knowing us or talking to us. It feels nice.

Discovering Unity

We took a risk by choosing to create The Graveyard with a new technology. But using Unity (and Mac OS in the case of Michaël) turned out to be a very pleasant experience. Well-designed software is such a joy to work with. We don't get that nearly enough on Windows.

Artistic recognition

The Graveyard was not intended to be a commercial game. Selling it was part of the artistic concept, not an attempt to make money. And it looks like the project is receiving the recognition we believe it deserves. It has already been selected for the Brazilian File festival and for the Indiecade showcase during E3 in Los Angeles. There's also interest from Mediamatic in the Netherlands to show the piece in an exhibition. And there will probably be more.

The Graveyard is not as easy to display in a social context as The Endless Forest is. But we think it can work.

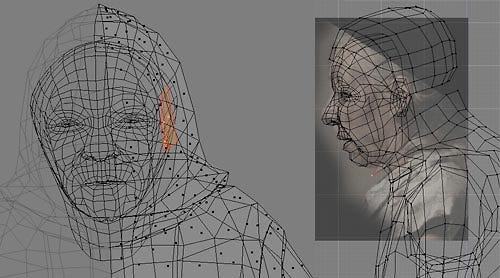

Modeling the character in Blender

No break-even

The return on investment through sales was far too low to get even near to breaking even (details in the last part of this article). Technically, this is not a failure because the project was not designed to be commercial, but to only be a parody of a certain business model. And the fact that it was non-commercial was instrumental to acquiring the arts funding in the first place, commercial and artistic being largely considered mutually exclusive here in Europe. So not selling well is in fact a bonus in some weird way. But still it would be nice if a project like The Graveyard could be made solely through the support of its audience.

No publishers or distributors

Maybe we could get closer to that ideal if major distributors would be involved with it. We asked the friendly people at Steam but they didn't see The Graveyard fitting in their offer or appealing to their audience. Neither could we, really, but somebody is going to need to do something at some point on the business side to make this dream of an artistic games medium a reality. Distribution is everything. Unless we want artistic videogames to go the tragic way of video art.

Apart from a few websites that mirror the trial download and some magazine cover CDs, The Graveyard is solely distributed from our own website. We talked to Steam. They didn't want it. We asked Manifesto. They didn't respond. We were scared of approaching the portals. The Graveyard is a difficult game to position. But we're certain that if it would be distributed through other channels, it would find a much bigger audience, even within the gaming public, but certainly outside of that. But there is no real distribution channel for these kinds of small games.

Too little time/money to make everything perfect

This is also a double-edged sword. We would have loved to have more time/money to improve the quality of the game. But the small size of the budget was important to get it approved by our funders. And the small scale of the project actually suited very well within our workflow (which is mostly focused on production of The Path these days).

But in an ideal world, yes, we would have loved to have been able to put a little more time in the production of the game.

It's kind of pretty. But it's wrong. We wanted the titles to fade in and out. But some bug prevented this

Some bugs

The Graveyard is a very stable application overall, thanks in large part to the Unity engine. But some things don't work. Fading GUI elements didn't work across platforms. We caught that before publication. On some Windows machines, the game takes a long time to start up. For some users, the avatar does not move forward -- we have no idea why. And the latest upgrade of the Mac OS has messed up the shadows when you run the game in anything but full screen mode.

This made us realize that, in the future, we need to reserve some of the budget for post-launch patching, something we hadn't even thought of now. It's nice to produce a small project from start to finish and experience some of the problems on a small scale so we can prevent them later when we're working on bigger projects.

Faulty script to track downloads

We had created a PHP script to track the number of downloads per version and per platform, hoping to get some interesting data that would help us with marketing of other projects. But the script we made was too simplistic and it couldn't handle the traffic peaks caused by The Graveyard's popularity. So we lost a lot of valuable information because of this.

The Graveyard is not a commercial project. The fact that we distribute it as a shareware game was an artistic decision, not a commercial one. We wanted to challenge people's assumptions about what they pay for in a game. Not seduce them to spend money (we'll experiment with that in other projects). Hence the almost symbolic price of 5 U.S. Dollars (or, for us in Belgium, little over 3 Euros).

As a result, the critical response to the piece is far more important than its commercial success. We'll offer some business details at the end of this chapter, but we'll look into the hearts and minds of the audience first.

Critical Response

The Graveyard was released on March 21, 2008, for both Mac and PC. Virtually immediately, it was picked up by several web publications, resulting in an enormous increase of visits to our website. The Graveyard literally doubled the amount of web visitors for two months (to over 70,000 unique visitors per month). Which, much to the chagrin of our web host, resulted in over half a terabyte of bandwidth used by our little old lady in March and April.

People found our website through links from some 200 articles published in all corners of the internet. The article in the Wired game blog was by far the most important channel (12,000 hits), followed by the Apple game downloads section and a mention on Boing Boing (each good for 6,000 hits). Heise (DE) sent 5,000 people our way, GNN (TW) 4,000 and Joystiq (U.S.) 2,600. Most of these simmered down after a month or less, except for the Apple site, which is still directing people to us (down to about 200 hits last month).

Many of these articles are fairly short and transmit our challenge to the audience faithfully: I dare you to click on something that sounds so strange and lame. But some articles went deeper. John Walker's preview on Rock, Paper, Shotgun was lovely. Even the comments were interesting -- for a change. We were very happy with Chris Kohler's post on Wired as well. Other memorable articles were Eric Simonovici's post on Over Game (FR), Simone Tagliaferri on Ars Ludica (IT), Joris Dirickx on Jouw Games (NL) and Deirdra Kiai's thougtful criticism on Adventure Gamers (US). There was also a nice article in GMR magazine by Niels ‘t Hooft (NL).

"Interactivity is a powerful thing. The Graveyard could have been a short film on YouTube and lost none of its presentational qualities, or its message. But the very limited interaction you have with the character -- you can walk her forward and backward, or turn -- instantly makes the connection deeper and more powerful than it would have been if you were simply watching." - Chris Kohler

"From the realistic birds flitting about to the way the sounds of the street fade as you move further into the sanctuary, Tale of Tales again demonstrate a remarkable capacity for crafting ambience. The music, the particle effects, and perhaps most of all, the realistic clouds and their effects on the shadows of the graveyard, all envelope you in this single moment." - John Walker

"Le titre de Tale of Tales, lui, fait peut-être le choix de mettre plus franchement le joueur face à l'ultime game over, presque un tabou dans un monde où la mort, aussi violente qu'elle soit, n'est généralement rien de plus qu'une formalité, et une perspective d'autant plus dérangeante qu'elle est ici aussi inattendue que définitive." - Eric Simonovici

Overall, the reactions to the game (gathered from the articles, their comments sections and personal messages), fall into three categories.

Of course there is the expected response of the typical gamers whose desire for zombies whenever they see a cemetery is apparently insatiable. They tended to describe The Graveyard as "boring". Of course.

A little bit up the ladder of human civilisation, we find the people who were turned on by the idea but turned off by the actual experience. They were "disappointed". From what we can see, this was either caused by a failure on our part to maximize the qualities of the game or by certain expectations coming from the player.

Despite the fact that games are supposed to be interactive, many gamers still seem to be incredibly passive when it comes to the meaning of their entertainment. They expect to be spoonfed and don't seem to have any experience with literature, modern theater or fine art (or even art films) which require active participation, not just of thumbs and index fingers but also of heart and brain.

A final type of response was the simply "delighted" one. These people really enjoyed the game. And/or they were happy to see the experimentation that we're doing with the medium.

Overall, we feel that the game was received very well. We experienced far less rejection than we had anticipated, even when people didn't exactly like the game. Perhaps a sign that games culture is maturing?

Peer response from the indie game scene was a little odd. The Graveyard was regularly compared to Jason Rohrer's Passage because it deals with similar subject matter. Often, however, our fellow game designers and indie game fans found Passage a superior product because it uses a conventional game structure to convey its message.

To some extent The Graveyard is disqualified beforehand because "it is not a game". That was also the response of Jonathan Blow when we proposed to show The Graveyard in his Experimental Games Workshop at the Game Developers Conference. The gameplay in The Graveyard cannot be considered experimental/interesting/etc. because it cannot be considered gameplay. Or something along those lines.

There was another strange response that we heard from several game experts. When they realized that The Graveyard was a work of art, their reaction was to try and uncover its meaning. And they were confused when they didn't find a clear message. It's as if they, even when looking at art, couldn't shake the inclination to deal with everything in the world as a puzzle to be solved.

This is all very interesting for us as designers. But in the end, what matters is the response of the audience at large. On top of the numerous spontaneous compliments from random strangers, we're very happy and proud that The Graveyard was selected by the IndieCade festival and nominated for the European Innovative Games Award.

Downloads and Sales

In the absence of publishers or portals, we distributed The Graveyard virtually exclusively from our own website. As mentioned above, the script we had written to count the number of downloads failed several times. The total number of downloads we recorded so far is around 120,000. But the real number is likely to be a bit higher, since we literally lost count a few times.

One of the remarkable outcomes of this project for us is how succesful it was with Mac OS users. It was the first game we ever released for that platform and a quarter of the downloads came from Mac users (well over the 7 or 8% market share that Mac supposedy has, which seems to correlate with our website's visitors). And it gets better when we start looking at sales figures.

In raw figures The Graveyard did not sell well. If it would have been a commercial project, it would have failed. To date we sold 400 copies -- enough to by a new TV, but far from sufficient to sustain our company.

As to be expected, most of these sales happened in the first two months after the release. After that, the "long tail" kicks in. In the first two months we sold well over the amount of copies that we sold in the subsequent half year. The question is now how long this tail will become. Not that there is even a remote chance that The Graveyard could become a commercial success. If the current rate of sales would continue (unlikely), we would have made our development budget back in 15 years!

Currently, in our long tail, we're selling an average of 25 copies per month. At this rate, we would need to have 60 games on sale to keep our company afloat. And at the three months of production time that it took to make The Graveyard, it would take us 15 years to create 60 games.

More fun with numbers! A bit more pertinent now. With the huge amount of downloads versus the low amount of sales, the conversion rate of the Graveyard was pretty disastrous: only 0.34% of the people who downloaded the trial actually bought the full version. Interestingly, if you divide up the numbers per platform, the conversion rate for Mac users is more than double that of PC users! They download less but buy more. Which leads to an interesting end result of 44% of sales being the Mac version, almost half. So it seems that the Mac platform is definitely worth pursuing if you make artistic games.

Ultimately, we consider The Graveyard to be a succesful project. It served as an illustration of our ideas about game design. And those ideas were met with sufficient positive response to be encouraging. We will continue along this path!

Businesswise, The Graveyard doesn't count as a good test, because we had no commercial intent whatsoever. So we're still in the dark about whether making small games like this is a viable enterprise. This is something we will explore with another project.

It is heartwarming to know that over 100,000 people have played our game. That's a staggering amount of people, more than would ever visit any media art festival or gallery exhibition. It's nice to receive such confirmation that our choice of medium is not as insane as it may seem to some.

Article written by Michaël Samyn between May 21 and November 2, 2008. The interviews with Laura Raines Smith, Gerry De Mol, and Kris Force which follow, as appendices, were conducted via email and rearranged a bit for the sake of storytelling.

We have been working with Laura Raines Smith from our very first project. In fact we have never worked with another animator since. We tried a few people before her, but none of them succeeded in doing something as seemingly simple as animating a little girl.

Even with the aid of motion capture (mocap), most animators made the character move like a truck or play with a ball like a professional basketball player. Not so Laura -- maybe because she's a woman.

She adds a level a subtlety and detail to animations that makes them very expressive and charming. Working with her is like working with Santa Claus. Every day there's a new gift to unwrap in 3D Studio Max. She always adds something delightful, something surprising to the animation.

For the occasion of this article, we poked her brain a bit about how she does what she does.

The avatar's animations in 3D Studio Max. Soon to be released as a nude patch

How did you approach the task of animating the old lady in The Graveyard?

Usually my process for animations is to ask the art director what they are looking for and throw out some ideas of both extremes. Is she spry and agile or old and decrepit? I believe Michael and Auriea were looking for dignified, but started to like the gimping animation I found in a mocap file.

Another thing that influences how a character will move is how they are built. If they have short legs then they'll have to take shorter steps. If they are thin, they will move faster. If they are old they will move slower. If they are sad, they will look down. You just piece together simple postures and speeds and try to keep them consistent throughout the animations.

What do you use for reference?

I will sometimes use mocap as a start -- then have to reduce frames, change the posture, and make sure it loops etc. The mocap files are great for getting some of the subtler ambient motions in the spine, neck, and arms, but they can be hard to get to loop. Since we see human motion every day it is easy to see flaws in human animations. For animations that require a lot of quirks, as in old age, I thought it was best to use mocap so that she wouldn't start looking like a caricature of an old person.

Another process I used for the remainder of the animations was to film myself doing the movements, aka rotoscoping. I then turn the .avi into a .mov file so I can frame-by-frame the .mov and create postures (by eying the footage) in Max on the old woman on every five frames or so. Then I'll go back and delete and slide keys on certain body parts to make the motion less uniform and create smoother arcs. I have a whole embarrassing .mov archive of me, my friends and my neighbors acting out mini-scenes for my animations.

There is also great internet reference to be found on the BBC's motion gallery, YouTube, and other miscellaneous sites as well as footage from feature films. I spent the first day just downloading and creating a reference archive.

Your animations have a subtlety that we rarely find in other animators' work; are you aware of this? What's your trick?

For human animation I guess I'm always trying not to draw too much attention to a particular movement. If it makes sense physically then it is pleasing for me. If a character moves too quickly for its weight or too much of its mass is over a non-weighted foot it makes me wince. I tend to slow things down in order to give the character time to think. I think that the subtlety could be linked with the slower speed and trying to get the characters' loops to be as smooth as possible.

Animations are very important to express a character's personality. Are you a keen student of body language?

I don't sit at parks and watch people's body language but I have been observing humans for a lifetime. :) I think it's easier to "try on" postures directly to the 3D model and see what works for that character's body and personality. It's pretty freeform. I also film myself. I realize that I can get into the limitations of my personality and my body type so I will film friends as well. One interesting thing I've noticed is that the performance can be too natural if you go based solely on rotoscoping. People expect to see more charicatured postures. You have to try to balance between the natural and stylized.

Something that we have been wondering about for a long time: why do so many game characters have stiff and awkward walk cycles?

Well that is probably a three part answer (maybe four or five). 1) You see walks everday so if something is off in a human-animated cycle, you notice it instantly. You might not see the same stiffness in a Skeletal Mammoth that has risen from the dead to chauffer an Evil Demon. 2) Many animated cycles are incredibly symmetrical (copy/paste opposite). If you look at your face, the right side and left side are not the same. That is true in walk cycles, and seeing a mirrored image of the arms and legs moving, your brain will see the pattern and thus it will look stiff (if not mechanical).

3) When you walk, you lift your legs and put them down and move forward. While this is all happening your pelvis is rotating up and down and back and forth. This causes your spine to counter-rotate up and down and back and forth all the way up to your head, which sways gently but always remains facing forward.

Your arms are swinging back and forth opposite of your legs but slightly delayed because they are also reacting to the movement of the counter-rotation of the spine. The pelvis's height isn't highest when it's weighted on one leg directly under it but slightly after when the other leg is beginning to swing through. The pelvis is also swinging back and forth to the weighted leg. The stiffness that you see probably starts in an under-animated pelvis. Ha ha, I guess that should have been my short answer.

You also work for more traditional game companies; what's the difference with working for a small art team like Tale of Tales, if any?

Many if not all of the characters I've animated for game companies have either been heroic and manly or cartoony and stylized. The Tale of Tales' characters have been for the most part natural and subtle. Quite a relief from sword-swinging and blasted deaths. The only other game that I have really enjoyed working on was Zoo Tycoon because it too was naturalistic animation (of animals). Being a female animator probably has a lot to do with it. Imagine if you were the sole male animator at your company forced to animate the Barbie franchise for years on end. You might know how I feel. ;)

You once said that working with Tale of Tales has been the highlight of your career. Can you explain why?

I have had a lot of freedom to express myself working on Tale of Tales's games. I think my natural style fits with their naturalistic games. They are also more gentle and open in their comments which makes me take extra steps to try to add more to the animation. Instead of sending me links to footage of other games and saying "make it look like this" they send me links to abstract art and old movie clips. Having that freedom of expression can unlock many more possibilities.

Early work in progress screengrab of The Graveyard with the first animations of the avatar by Laura Raines Smith

Next generation hardware allows for more animations everywhere. What is the future of animation in games?

I can't see big budgets and huge asset lists going away. But all of that is being poured into games that have the same mechanics. I see a huge void in the types of games being produced. I also think that some people don't really care about high-end graphics as long as the story and gameplay are interesting. Huge Void. I try not to think about it.

Do you think there will just be more and more work for animators to do? Or will there be a technological answer to the problem? Like motion capture or generative animation (as in Spore or the things that Natural Motion are doing)?

I don't know enough about generative animation to answer that question. I did see Spore last year and thought the animation was herky-jerky, and I realized why mother nature never intended us to have three legs. As far as Natural Motion I remember having a look at it and being quite impressed. I don't know how they can program in "character" though. But the way it responds naturally with the environment is very exciting. I guess I'll have to become a painter again or go and work on animated shorts or 2D animation that still has somewhat of a following.

If there would be one thing that you would change about animation software, what would it be? What bugs you the most?

I am certainly no expert in 3D animation programs and there's a lot I've never used. I only have experience with Max and Maya. Max's character studio has so much already built in it's easy to transfer animations from one character to another or mix and match in the motion mixer.

However, I can't stand the track view in Max and avoid it as much as possible, while in Maya I love the trax editor and moving keys and adjusting tensions and typing in exact values with ease. Maya's interface and key editing blows Max away. I wish Max was as elegant as Maya and Maya had more built in character rigging and animation features.

I can say that we probably wouldn't have been able to use Maya on any of our projects with the budget and time constraints. Max just has a superior workflow. Maybe now that they are both owned by Autodesk they'll marry the two.

We first approached Gerry De Mol out of the blue after hearing a song from his "Kleine Blote Liedjes" album ("Little Naked Songs") on the radio. At the time, we were looking for a composer to work with on 8, having decided that Pergolesi and Beethoven were a bit too heavy-handed for the game. As it turned out, Gerry was the perfect match for 8.

Not only did he make simple moving songs with minimal orchestration and unexpected instruments, he also had this entire other life of being a "world musician" with Oblomow. Gerry is an expert player of all sorts of exotic string instruments and many of his compositions refer to Middle Eastern traditions (which 8 referred to as well, in its visual style).

We were unable to find sufficient fundng to produce 8 at the time, but when we needed a song for the options screen of The Endless Forest, we asked Gerry. Then later when we developed Abiogenesis and need more music for live performances in the Forest, we asked him again to make a whole bunch of songs. We have returned the favour by creating a 2D game for his "Min en Meer" album.

The choice for Gerry as composer for the song in The Graveyard was clear from the beginning. Very few musicians have the courage to make art about the mundane and even fewer have the talent to be witty while doing it, and incredibly moving at the same time. Gerry is a rare artist and the perfect match for the ambiguous atmosphere we wanted to project with The Graveyard. Let's see how he feels about this...

The song you created for The Graveyard (entitled "Komen te gaan" or "Come to go"), is about cleaning graves. Where did the inspiration come from?

"Komen te gaan" is a quite regional euphemism for dying, means as much as "arriving to the departure", has a nice paradox in itself. The inspiration comes from where I grew up. I lived very near the local graveyard (so we had a lot of neighbors, all quiet people) and as a kid we used to play in the graveyard.

At one time, when the "old graveyard" was nearly full, they created a new graveyard with asphalt lanes that meandered round nicely trimmed lawns, but no grave was dug yet. The place was big and it came out to be an ideal terrain for practicing rollerskates. My best friend's grandfather was the gravekeeper at that time, now 40 years ago. Graveyards are ideal for playing hide and seek as well.

Also, my mother's father died very young, so more than once a week my mother visted the graveyard. Once a year all family graves where cleaned for All Saints (1st of November) -- the blue stone was thoroughly cleaned with a bottle of acid. But my strongest memories are from the days just before All Saints, owning a pub alongside the graveyard, my parents and grandmother sold Chrysanthemums in the days leading up to November 1st, which spread a sweet smell for weeks through the house.

In most cultures, cleaning graves is a way of taking care of memories and people who are not there anymore. Most people talk to the deceased when doing that, it's got the power of a ritual which is very personal and soothing.

Could comment a little bit on some of the lyrics? Perhaps illuminating some things that might have been lost in the translation?

From year eight to year forty Yes, Irma was still young‘t Was a German with consumptionToo big a heart, too weak a lung |

|---|

What was "a German"? What are you referring to? She reads from the grave, the girl Irma died in 1940. Germans were all over this place then, apparently she knows the story. Irma (about her age, I suppose) met a German, she had a big heart, fell in love, but the German had consumption, she caught it and died from it because of her weak lungs. Apparently very swiftly. |

Renée, she had fibroidsAuntie Mo, while she was asleep,Fell down into a dreamAnd was never picked up again |

Just a list of how they died. One is mysterious, Auntie Mo. By lack of information or vocabularly, when people walk the paths in a graveyard commenting on who they pass by, use expressions like "he fell dead", "he suddenly died", "she never woke up". It struck me as quite possible that, the old lady can think that someone dying in her sleep for no apparant reason might have died from something that happened in a dream. |

Look that's Emma, stillborn,Take care you don't step on herHer portrait is long lostA little blue cross, never baptized |

Why a blue cross? I remember a very touching place in a hidden corner of the old graveyard at our place. There were some light blue crosses lined up, no photo, just a name and one date. Not two. They were the little babies that were stillborn, they had no right to a proper grave or a proper funeral because they were not baptised in time. Maybe this made me see very early the cruelty of religions to people. |

And Roger, that was cancergrew too big for his own goodWhen ivy gets too tall, there'sToo much shadow. Pruned away. |

Roger is the only persona who really existed. Cancer happens when we overgrow ouselves literary.. and sometimes also in a figurative sense. |

Acid on graniteWhite bubbles, yellow foamSteel wool to clean the rustScratch away the year and dateAnd a chisel for your own nameFor when we come to go |

"Acid on granite" is not exactly a correct translation is it? No, I have a Brother who is a geologist, here's what he had to say on the subject: "Arduin seems to be called Belgian Blue Stone in English, a kind of Limestone. The specific kind of acid is hydrochloric acid or hydrochloric or muriatic acid. The yellow foam is a result of chalk settling on the blue stone. Therefore the cleaning is caused by the acid taking away some micrometer from the blue stone. The acid, however, will not bubble yellow on granite unless someone has peed on your grave". Which is a soothing concept, I think. She thinks of a clean grave for herself, the tools she had to clean the graves she visited, all you need now is these tools and a chisel to engrave her own name somewhere as she knows her death is imminent. |

From between Jesus's legsI would like to pluck those websI'd wipe the sand between his toesIf I could still bend over |

Who is the "I" who is speaking? It is the old lady, she sees a neglected figure of Jesus on the graveyard with webs between his legs and sand on his toes (happens from raining) and still would like to clean the guy, but she can't. The cleaning has become a memory, as well as the people. When the rituals of death become memories, I suppose we enter a kind of peace. |

I want a cherub made of chinaa black marble bedspreadstone flowers will sufficeto keep me nice and warm |

What are these stone flowers and how do they keep you warm? Some graves are terribly kitchy as everybody knows. Some people put little nude cherubs and awkwardly colored stone flowers on graves, it removes the need for the maintenance by bringing flowers and creates maybe an aura of indestructability. She, who has been cleaning graves all her life, suggests that she is happy with having her monument, but essentially does not want to be a burden. Flowers are a gift from the heart, but she is happy with stone ones, to paradoxically keep her warm. Meaning -- again -- she does not expect too much anymore. |

Acid on graniteWhite bubbles and yellow foamSteel wool to clean the rustScratch away the year and dateAnd a chisel for your own nameFor when we come to goHere is calm, here is safeMaybe next timeNext time perhaps, I will stayThen I'll be here no moreNo more |

She finds calm here, I particularly am fond of yet anythor paradox in the text that next time, maybe she would "stay", meaning she's "not here anymore". |

You first made another mix of the song but we thought it was too heavy; now that you can see the finished project, do you agree? Or do you still prefer the first version? and if so, why?

I do not particularly like the first version more than the other. I like to blend in projects, so this version works very well with the game. I'm very happy with the result and like to present it to people as an empathy machine with old people, so I'm proud of being part of it. For my MySpace I considered putting on the earlier version, but I decided against it, so apparently I like this version as much. The first version would have been okay if the person was a man, it's got more coarse singing, it's slower and lower. The singer [in that version] is more a persona, as now it's more of a storyteller. Therefore this is better for the game, I suppose.

Is the music of "Komen te gaan" inspired by any kind of traditional music? What other ideas did you have that didn't make it?

It has no specific ethnic roots. It's a bit of a slow death march for optimists made light and with a deliberately struggling rhythm that always seems to come too late. It's more inspired by the movements of an old lady who thinks she will move her foot, but the foot reacts just a bit too late. So does the rhythm and the little banjo solo.

Things and directions do not react as you would want to any more when getting older, so the solo gets lost in itself -- as does the lady, I reckon. I would have liked to keep the harmonium from the first version, but it swept away all the relative lightness. What I would have liked to have done -- but time lacking, I did not -- was create a slow polyphonic seemingly religious yodled version of a very popular pubsong coming from within the chapel. The text goes: when we're dead, the grass grows on our tummy. Maybe later.

You work with musicians from all over the world and your musical inspirations come from many different cultures. Yet you always write songs in Dutch. Doesn't this limit the exposure of your work?

Maybe, maybe not. But I do not think there is any choice. If you want to obtain a certain level of significance and subtlety in lyrics, you cannot but do it in your own language. I learned that you either have to be yourself or choose a persona and a style and a statistically measured least common denominator in taste to become famous. Creating exposure instead of expression. As I'm too old, too ugly, and too male for the latter, I'm stuck on the former way of expressing myself: trying to be or become myself.

What projects are you working on at the moment? Any new albums coming up? Any games?

I'm working on a solo album, hoping to release it soon, but I have no deadlines. I might suddenly make it in a week, or it can stay on the shelf for years to come. I'm in a writing period now, which makes it more difficult, with over 40 new songs to choose from. And then there is this doubt whether printing CDs is still a good idea. Looking for new ways of creating things and having a bit of an income as well.

I'm touring with a show I created called The Portable Paradise, in which three singers sing about their lives (from a book I wrote with migration stories of singers from all over the world). Touring in November, it's a new way of working with film and live music and storytelling. The music is from myself, Ethiopia, Armenia, and some other inspirations.

I'm performing on my own in small theaters and house concerts (great fun to do) and performing in two theater pieces at the same time. One based on the poetry of Flemish poet Pat Donnez for which I wrote some music and perform on stage. The other a new project by theater maker Michael De Cock with Senegalese actor Younous Diallo about the boat migration from Senegal to Tenerife, a horrific story in which I use the sea, some water, a guitar, a rope and a motor as instruments.

Where can people buy your music?

They can hear it on MySpace and I'm planning to put some of the music on iTunes. Older CDs can be obtained on my site www.gerrydemol.be.

We met Kris Force when Jarboe invited her to assist with the soundtrack for The Path. At first, we were a bit worried. Especially because Kris is a seasoned professional in the games industry. She started by asking us all sorts of professional and technical questions only half of which we knew the anwser to. We were worried that she would not have the artistic flair that we require in our collaborators.

But we were quite wrong. In the meantime, Kris has become an invaluable part of the creative core of Tale of Tales. The Path does not contain any sound effects, only music, but when we needed a sound designer for The Graveyard, we asked if Kris could help us. And as it turned out, she had a lot of experience in the field. She lovingly created the rich palette of sounds that make up one of the most immersing features in The Graveyard.

You have also worked for more traditional game companies. Can you talk a bit about what you did for which games?

Yes, I worked at Maxis/Electronic Arts where I was a sound designer for The Sims. I was a voice director for Sims Bustin' Out for PS2 and Xbox, which was super fun because the Sims speak their own language, Simlish, which is a form of gibberish. All performances are improv and the direction is all intention based. Actors work in tandem because they respond to each other and have greater enthusiasm then if they were alone. It was great fun.

The Urbz game was a series of Worlds featuring urban subcultures such as goths, skate punks, bikers, indie rockers, hip-hop gangsters, etc... The player unlocked each district and earned cred along their way. I thought the game was fairly weak in general.

I took care of the UI design for the entire game, most of the in-game music other than the tracks that were licensed from The Black Eyed Peas. I composed a few tracks myself. One that was particularly fun was a piece for the dancing van which was a van that transformed into a boom box. The Sims games have an in-game radio object and for The Urbz each culture in this game had its own radio station.

In previous games The Sims radio tracks were written and produced by music houses and often sounded generic and disingenuous (except for the bluegrass!) but for The Urbz I asked existing recording artists if they would re-record their vocals in Simlish. Everyone was more than willing to comply. The believability of the music took a huge step up. The design concept became studio-wide and the game started to attract big artists such as New Order, Willie Nelson and Hillary Duff, etc. Who knows what they are doing with it now. I left EA two years ago.

For Sims 2 for console I did the same tasks and some of the more musical sound effects. I especially enjoyed designing the genie lamp. For Sims 2 Pets for console I was the senior voice editor, which was fun because people performed all of the animal voices. Or I should say person: Roger Jackson who is the voice behind the Monkey Mojo Jojo in the Power Puff Girls and the killer's voice in Scream. He is so talented that it was perfectly fine to listen to his voice for hours on end.

What's the difference between working on these big games and working with a small art team like Tale of Tales, if any?

Well first of all one has to have something of a sociopath personality to survive at a big game company. They can eat you up and spit you out like any big corporation -- possibly even worse. One should enjoy lots of late night pizza in the company of men in their mid-twenties. To some this would be a dream come true. The culture is interesting and sometimes strange and alienating. EA is near Oracle in Redwood City (California) where the area is exclusively corporate parks. Do they have corporate parks in Europe?

It's like working in Disneyland without the rides. I had an internal relationship with the manicured landscape. In a big game company very different groups of people are put together; engineers, programmers, mathematicians, conceptual designers, sound designers, visual artists, management, and business people all under the same roof. There is an inherent awkwardness with that.

An average team for a console title would be 60 or so people and the production cycle would be as short as six to nine months. In some ways working with Tale of Tales is similar to working for EA because EA divides people into smaller cells or groups of four to six people and these are your primary teammates. It's considered a very effective working dynamic. I would have to agree. I see Tale of Tales functioning this way.

One of the biggest difference is that a big game company makes products with a two to three year shelf life and Tale of Tales makes art games for a discrimating audience. When big profits come into play, everything gets hacked to lowest common denominator. There is a huge difference in the integrity of a product or art piece when the designers have executive power.

In The Graveyard, the soundscape is generated by the game engine with sound clips that you created. Do you wish you had more control over the way in which the sounds are played and mixed in the game? Would you like to program that engine?

I didn't have any nagging urge to take over the audio engine for The Graveyard. I'm fairly confident in Michael and Auriea's decison making process. I am interested in the technical complexities of the sound engine. Understanding these helped me to create the best content. Does it score vertically and can it score for different times of day? How does it map footprints and does it have collision detection? Are there any dynamic effects such as room reflections? These are the kinds of questions that I would ask.

I have programmed engines in the past and I am always game to learn new tools.

What was your general concept for The Graveyard? What feeling were you going for with the sounds?

I was after a believable and naturalistic feel for The Graveyard, but one that was not regionally specific. The sound is isolated and lonely. Initially you hear sounds from the outside world but they fade quickly and you are completely alone inside the graveyard. Your companions are birds and insects and the sound of grandmas hobbling.

There is a change in climate but not time. The sun becomes hotter with cicadas but the time of day does not change. This is a design choice, and probably because Grandma has come to the graveyard for one simple task so the game doesn't really need to go into the evening. If it had, I would change the soundscape.

When the music plays it completely disrupts the world and breaks the narrative. But so might dying, therefore it is symbolically effective.

Do you play games? If so, how do you feel about the use of sound in games? Are there any games in particular of which you admire (or detest) the sound design?

I tend to like comic and playful titles and mini games such as Electroplankton, Wario Ware, Hot Pixel, Katamari, Destroy all Humans, Rampage, etc... The sillier the better. The sound isn't generally the main focus in these titles but they are the ones I enjoy playing.

I think the sound is fantastic in flOw for PS3, and Audiosurf. Some of the better sound I've heard in games can be found in the fantasy, horror and war titles. Some that come to mind are Metal Gear Solid, Quake, BioShock, Mass Effect, Assassin's Creed... can you tell I live with a teenage boy? I am exposed to a lot of games whether I play them or not.

Do you have a large library of sound recordings? Do you make your own recordings? In a studio with your feet in a sandbox? Or do you go out and capture sounds in the field?

All of the above... I do whatever is necessary to get the sound I want and then I save it in my ever-growing library. Sometimes it is easy and you can find something perfect or something that would require only minor tweaking in a library. Sometimes there is not a match and you have to create it or capture it or find a clever substitute in the library.

Substituting sounds can support the narrative for example, I worked on a film where the lead character was mentally ill, so whenever he saw other people walking and talking, hooves and pig oinks and squeals were subtly mixed in. You have to stretch your imagination and think outside of scale. You are referring to Foley with the footsteps in a sandbox. It's Jack Foley: the first "sound designer" in Hollywood in the 1920s. I have done that too. I have made sound effects in the studio and gathered them in the field.

You are also a musician. Can you talk a bit about that aspect of your career?

I stay very busy musically. I have created works under the moniker Amber Asylum since 1996. I am currently working on the sixth full length CD, due to be released in early 2009 on the doom label Profound Lore based in Canada. Still Point, AA's 5th CD released in May 2007 was voted one of Terrorizer magazine's top 40 albums of 2007. There is an accurate description of this project on Wikipedia. My primary collaborator in Amber Asylum is Leila Abdul Rauf. Our fundamental agreement is not to limit ourselves. We also play with Eric Wood from Bastard Noise, Sigrid Shei from Hammers of Misfortune, Chiyo Nukago and others.

A project that is still in Development that is quite exciting is AEAEA. AEAEA is a collaboration between Jarboe, myself, Anni Hogan and Julia Kent. Julia Kent is a fantastic cellist who has played with David Tibet and Anthony and the Johnsons. Anni Hogan has composed many of our most beloved songs performed by Marc Almond. She is a pianist, songwriter, producer and DJ. And then there is Jarboe as the primary vocalist. We have done a few tracks already. It should be fantastic.

I have contributed to many CD's as a guest. This is actually how I met Jarboe [who is composing the soundtrack for The Path -- note by ToT]. I performed on the Swans CDs, Soundtracks for the Blind and Swans are Dead. I was also invited to guest live for the Swans last San Francisco show. It was a great honor. I played on six Neuosis CD's and Steve Von Till's solo project. I've played on a lot of CDs. I can't really remember them all.

Most recently I cameo on the upcoming Saros and Giant Squid releases. I am also on Jarboe's Mahakali CD, out October 14th. There is an extremely indulgent four minute electric violin solo on Jarboe's Mahakali album called Violence which I think is very cool ;). I work quite a bit with Jarboe. We have very similar aesthetics.

In addition to all of wacky experimental and dark music I perform classical works as a soprano. I have a growing repertoire of art songs and arias. I like the concept of stripping things down to the bare minimum. There is nothing that really compares to standing and singing with no amplification.

How does you impressive activity as a musician combine with sound design for games?

I take a very musical approach to all of my sound design. Although largely intuitive, especially in UI design, imaging or logo design I will employ music theory to create a feeling of leading, discord or resolve... whatever the context calls for. The Graveyard was an ambient score so I wasn't able to flex this muscle entirely but it is always there looming. I may pitch things to relate to one another in the world... For example in The Graveyard, ravens may be pitched relative to meadowlarks, etc... I made the footsteps lower and slower to compensate for grandma's body weight and gestures. Even minor details like these become musical.

What's up for you next, musically?

My immediate musical challenge is plotting revenge against my new and very young neighbors who play dance music until 3 AM on weeknights. They have no idea of what I am capable of. I once used a recording by the Japanese extreme noise artist, Hanatarash, at full volume to banish a rodent from under my house. Maybe it would work on my neighbors.

Good luck!

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like