Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Spelunky creator and independent figurehead Derek Yu talks about the broadening definition of "indie" and why he's "very happy" with that definition being "kind of gray."

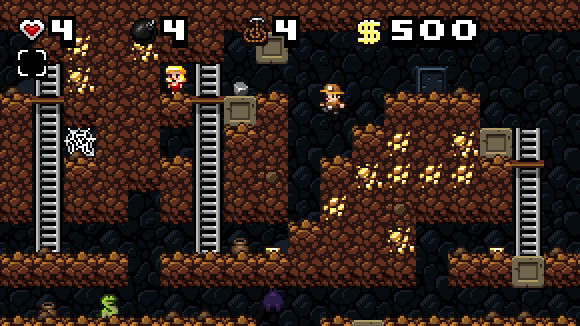

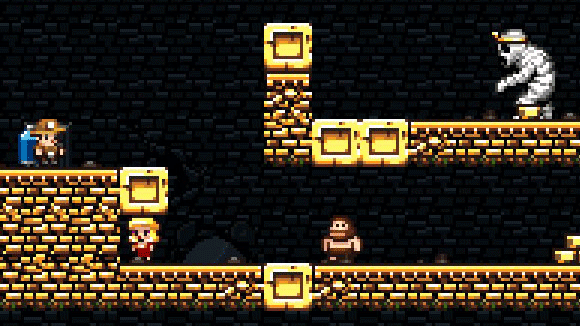

Derek Yu is co-creator of indie hit Aquaria, which won best game at the 2007 Independent Games Festival Awards, as well as creator of Spelunky, which is headed to Xbox Live Arcade after a successful PC release, and main editor of TIGSource, a popular blog and community site for indie developers. This makes him a prominent (and busy) face of the independent games movement -- if it can be called a movement, that is.

Indeed, where is the line drawn? When you're partnering with Microsoft for the release of your game, how independent are you? More or less independent than the guys who just put out games free and don't worry about commercial success? Does it matter?

Here, Yu address these issues, and the impact of sub-movements in the larger world of indie games, while also discussing what indie makes possible -- and which large-scale development impedes.

How do you reconcile working with this giant Microsoft conglomerate on indie stuff? This is happening a lot, not just to you.

Derek Yu: I personally don't feel like that's something that needs to be reconciled unless I'm totally bending over for them. If they say, "I want you to put a Toyota Yaris in Spelunky" and I do it, then yeah, that's something I have to reconcile.

They're just providing a platform in there. They're just helping me put the game on their system and providing the marketing and the distribution for my idea and work. I don't have any problem with that.

It's been interesting to me to see how indie games are evolving, because I feel like you almost need a new word for the stuff that Cactus is doing, and other stuff like that.

DY: Right. Uber indie. [laughs]

Yeah, like a super indie, "I'm just doing this for free, as a fuck you to everybody," kind of thing.

DY: Yeah. I feel like from here on out, there are always going to be those two sides. I feel like both are really necessary. I think, yeah, it's definitely going to get really fuzzy, and some people are just going to feel like if you put a game on Xbox Live or something like that or that if you work with a publisher, you're not indie. That's totally fine. I'm very happy with it being kind of gray. I don't know if a new name is really necessary. I mean, Spelunky started out as a free game, not a "fuck you," but more just something that I wanted to...

Well, they're not all necessary a "fuck you."

DY: [laughs] Yeah, exactly. You know, I definitely do have ideas for "fuck you" type games, just games that are kind of just totally just for me and stuff like that. That's kind of the nice thing about being independent, that I think you can jump back and forth between those two sides, you know? I don't know. I think it's great that guys are being successful kind of doing their own thing.

There are a lot of games coming out right now that have indie origins and have a really different feeling and aesthetic than a lot of your space marine and corporate games.

DY: [laughs] Right.

I wonder why you think that may be. My speculation -- you kind of triggered the thought for me -- is that maybe it's because people are making more personal games. They're like, "I'm interested in this."

DY: Yeah, I've been thinking about that. I think that honestly, once you get beyond a certain amount of people working on a game, and I don't know what the threshold is exactly... At a certain point, there are just games you can't do. Beyond a certain point, you have too many people.

I wonder, for example, that indie roguelike Dwarf Fortress, it's just a crazy simulation. It's probably the most complex game that I've ever seen, like ever. And that's just one guy. And you just wonder why a company that has some money and some resources doesn't make a game that's that complex. I think it's just they wouldn't. The priorities are just different.

For Tarn [Adams] and his brother, the two guys who make Dwarf Fortress, their priorities are making this really complex fantasy simulation. But for the big companies, graphics, for example, are always going to be a huge concern. That's going to be a huge priority for them. As a result, the games, I think, are just going to be different beyond a certain point.

But it's difficult to make anything that really says something when you have a whole bunch of people working on it.

DY: Right.

Unless you have a really, really strong creative director who's totally managing that experience, it's hard to maintain the voice.

Many people have been complaining about game graphics going away from what they enjoy and becoming all slick, 3D, everything shiny, and again bald space marines.

It seems like a lot of the people that are making the interesting games now that have the cool chunky graphics like Spelunky or Cave Story, maybe those people who got older and are now able to make video games are actually like, "Alright, I wanted this, and nobody's making it, so now I'm going to make it."

DY: Yeah, I think that's definitely true. The thing is I love graphics, so I think they should be a priority, but [the problem is] when it ends up taking over the entire development.

But, yeah, I think the kind of nice thing about indie games is that they can move sort of laterally as opposed to always kind of jumping forward with whatever the latest kind of technological advances are.

They can even move backward.

DY: They can move backwards, yeah. I think that's totally valid. I also think that there's really an opportunity for indie developers to make games that have the sort of depth that I'm not sure that you see in mainstream titles that just focus on the graphics.

Do you think that's because of the types of constraints that are placed on the different groups?

DY: I think so. You know, everyone complains about quick time events, for example, and that's just a result of just having graphics that are so good that you almost don't want to do anything with them. That's a way to try to make a cutscene interactive, as opposed to make a game, I would say. I think the priorities are just different. I think once you get beyond a certain point in terms of people and resources and money that you're putting into it, it just changes.

There's also something about making a creative product under certain constraints as an indie. You don't really have any money necessarily maybe or you're living at your mom's house or something like that. So, you've got these kind of stressful external pressures that force you into this creative outlet.

DY: Yeah, it's true. Suffering, I think, definitely helps the kind of artistic side of things. [laughs] I do agree that a lot of good games and entertainment comes out of people just going through tough times.

That's another interesting thing, whether these indie developers that do make it -- become successful -- where do you go from there? Once you have your blockbuster... As far as I know, right now, there aren't many indie developers that have had more than one hit because there haven't been many developers that have really released more than one game in a mainstream outlet.

I feel like The Behemoth is on the way there. Alien Hominid is really easy to understand. And Castle Crashers is easy to understand because it's a brawler, and everybody frickin' loved it. It sold like a million on XBLA, at least.

It's interesting to see what they're doing and where they're going. I feel like they're the one indie that everybody knows now.

DY: Right, right, right. They're definitely one of the few that have had a successful title as an indie developer. They have kind of a veteran status as far as this particular movement is concerned.

What are you doing to adapt Spelunky to XBLA?

DY: I'm in the process of doing graphics.

How?

DY: I'm going for much more of a painterly look. Kind of like the work that I did for Aquaria. It's going to be kind of cartoony and comical, but... In terms of 2D games, I'm still a big fan of the painted look. I just played Odin Sphere, and I really enjoyed it.

I guess you play with a bunch of different characters. I played with the first character, and that was about enough for me. But yeah, the aesthetic, I definitely like that.

I was going to say that it's a shame to lose the chunky pixely graphics, but I guess the PC version still exists. So, it's not like I won't have access to that.

DY: Yeah, that's the thing. I definitely want to kind of make it clear that this is not a replacement for the PC version. It's going to be its own thing. It's definitely based on the PC version. The people who played the PC version are going to get it right off the bat and be very familiar with it. But yeah, I like to try new stuff.

What do you see as the current shape of the indie game scene right now? I've noticed a trend, especially like in Flash games, toward trying to elicit specific emotional responses. There seems to be a lot more of that, like The Majesty Of Colors and Don't Look Back.

DY: "Art games." Essentially.

Have you noticed like any kind of trends in indie games like that, or any idea why things are coming about the way they are? Do you think about that kind of stuff?

DY: How do I want to put it? It's interesting because I feel like there's sort of this idea that you can have games that are almost like the equivalent of sketches in drawing, or something like that. I think it's the result of tools getting better and more freely available, that you can actually doodle with a game, in a sense. I think that's part of it. And also just being able to put something up, sites like Kongregate, Newgrounds...

TIGSource.

DY: ...TIGSource, and IndieGames.com, which are promoting these games. All these things just enable people to essentially doodle game ideas.

Kind of games vignettes.

DY: Yeah, yeah. These games, they're almost like prototypes that are a little more complete and polished. And I think for sure they deserve to be recognized alongside what I guess you might call "fuller" game experiences.

I think that the direct result of people being able to do these sort of sketches with games is that you can touch on sort of raw emotional feeling, and stuff like that. Try to just hit a nerve that's hard to hit if you're working on a game for months as opposed to weeks or days.

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like