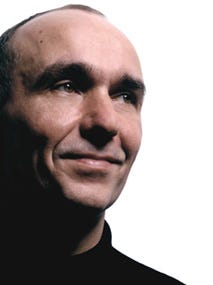

Peter Molyneux On Building The Future

The respected, effusive game developer Peter Molyneux speaks candidly about how Fable III didn't turn out to be all it could be, and how he hopes to reform production at Lionhead in advance of creating more games -- and juicy tidbits on Milo and more.

[The respected, effusive game developer Peter Molyneux speaks candidly about how Fable III didn't turn out to be all it could be, and how he hopes to reform production at Lionhead in advance of creating more games -- and juicy tidbits on Milo and more.]

Once again, Peter Molyneux's dreams seem to have been bigger than the realities that his studio has been able to achieve. "It didn't end up being the game that I dreamed it would be," he tells Gamasutra of Fable III.

But this time, he says, he intends to steer Lionhead's production process in a new direction -- one that will not only help realize the blockbuster goals he has for the series (he promised sales of 5 million units for Fable III at GDC 2010) but also one that allow the team to more carefully craft games.

"The game came together so late that we had so little time to balance and refine" some of the play mechanics, he says. "There was just a few weeks to do it. That meant that what could have been a great mechanic turned out to be a good idea."

In this interview, he discusses the refactoring of production processes, his feelings on indie developers, his observations on Zynga, and even just a little bit of what happened with the elusive early Kinect demo Milo.

You've been personally recognized, but you're also open about sharing credit with others you work with.

Peter Molyneux: It's difficult, you know, because anyone with any sense has sat down and thought, "Well, what does Peter actually do? Let's just empirically work it out; what's he do?" And, of course, all I do, really, is inspire people. I'm not programming anymore, and I don't fiddle with numbers on spreadsheets. It's more to do with inspiration. I think it's more true than ever before, that the rest of the team really deserves the credit.

What about knowledge transfer?

PM: Like mind melding? As in Spock? I don't do that; I'm not that skilled. If I could, I would!

But in terms of inspiring people, or sharing experiences.

PM: Yeah. It's interesting. I went to visit Zynga yesterday, and it was very interesting just talking through what it's like being a designer for 20 years. It's fascinating how sometimes you can spot people, or spot things that are happening, where you think, "Oh my goodness; that happened to me like 15 years ago!"

I think that's a lot of the job. When you get a little bit older and you have a bit more experience, a lot of your job is helping people through the mines of the mistakes that everybody makes. I've been doing quite a lot of angeling -- angel, you know, sort of guiding people.

I met a few people this week and just told them really obvious stuff that I wish someone had told me: Just focus on one thing, for God's sake! You're only six people; don't try to do three projects at once! Just focus on one thing and make that brilliant.

Say "no" to people; that's very easy advice to give, but actually if someone had said one thing -- just say "no" more times than you say "yes" -- I would have saved myself an enormous amount of trouble and angst.

When you look at the way things are, with people at Zynga or in mobile games, does it remind you of the past?

PM: Absolutely. You know, I was talking to Markus Persson -- he's doing Minecraft, which is absolutely brilliant, probably my most brilliant gaming moments in the last 10 years from playing that game -- and his story's almost identical to my story.

He started out and got some work experience -- mine wasn't in computer games; they weren't really around then -- but he got some work experience and then, one day, he took a deep breath and started his own company, and he was more or less known. It's kind of the same as me, and then just this feeling of "Well, I might as well just do it! I've got nothing to lose." I think that I really recognize that in him, absolutely.

In a way, many, many things have radically changed, but many things are the same. What's so fascinating at the moment is, if you look what's happened to independent games, and the fact that this industry can support success stories like Minecraft at the same time as supporting the totally blockbuster, triple-A, multimillion-pound games -- it proves that we're no longer the babies of the entertainment industry; we're starting to grow up. That's what the film industry does: It can support independent films, and it can support big blockbuster smashes.

Do you think that Microsoft, especially in your role above studios in Europe, is doing enough to incubate that independent talent or to give it a platform, or the nurturing it needs?

PM: Well, I don't think anybody is. I think that's in history -- I don't think anyone is. I think it's more you can do some very functional things which are very helpful: You can give out development kits and have conferences and have events like this, which really help, but I think it's giving those independent people maybe a small amount of funding which would be really good because obviously funding is quite often the biggest problem.

PM: Well, I don't think anybody is. I think that's in history -- I don't think anyone is. I think it's more you can do some very functional things which are very helpful: You can give out development kits and have conferences and have events like this, which really help, but I think it's giving those independent people maybe a small amount of funding which would be really good because obviously funding is quite often the biggest problem.

Although... I was going to say... I don't know about "harsh" -- I think there is a catalyst... Hunger is a great catalyst for creation. If your life is made too comfortable when you're starting out and you're creative, if you're not risking something and you're not a little bit hungry, I don't think it works the same way. That has to be carefully balanced.

Then just giving access not only to the tech, but also to some people that can say, "Okay, that idea's a great idea, but have you thought about it this way?" You know, just a little bit of time.

But I don't say that our industry does it any better or any worse; I can't think of any form of industry that does a great job with mentoring and with helping people to grow. We could do what business does and have television programs about mentoring people -- and we've got something called the Dragon's Den [in the UK] -- we could do things like that, but it's never enough.

I mean, there is, I suppose, an obvious thing. There is something which we've all been careless in -- the governments around the world, really -- but the British government could help with tax breaks, I think, which would help small people an awful lot because it's very, very financially tough to start development.

It's been quite a hot-button issue, particularly as there have been some studio closures in England. You see comments from Bobby Kotick saying he wants to exit the UK. Activision would like to potentially exit the UK because it's not competitive.

PM: It's tough! You know, just regarding everything about the UK, it is a very expensive to live; it is a very expensive place to have a studio. There is -- being British I'm going to have to say something about Britain -- there is something in the British psyche which is good at doing weird stuff.

I don't think it's a coincidence that Kinect Sports and Kinectimals came from England, because I think that we, instead of saying "Oh, well, Kinect might not work, and it has sync issues and framerate issues and all that," we just lapped it up. It's a piece of innovation that we would love. I think that's on the plus side.

On the minus side, it is a very hard place to set up a studio. Employment laws are very difficult if you've got a larger studio; there's all sorts of employment laws that are extremely arduous, to have HR departments to the eyeballs to cater to those. So it is a tough place, but it's still a very, very creative place. After all, talent is very, very rarefied in our industry, and there is some great talent in Britain.

That's a good spokesman role for me. I could be a politician.

You should talk to David Cameron about it (laughing).

PM: The frustrating thing for us is that we had a deal on the table with the government for there to be creative tax breaks, and then it was taken off the table again, because of the financial crisis.

Games like Fable III are quite large productions. You look at the way the console space is moving -- again, companies like Activision or EA are doubling down on big games that target the core audience. A lot of the breadth is coming in through the indies, but it seems like big package games are heading the other way.

PM: That's right. The bets get bigger and bigger, and the quality... I think that we have got a long way to go on the quality of Fable, and you just have to take a deep breath, knuckle down, and do it. If you look to the quality of a computer game just ten years ago, it is astounding, the difference. That's not going to stop anytime soon. What we thought of as being breath-taking, awe-inspiring, jaw-dropping graphics of something like Half-Life now seems incredibly retro. It's just... Take a deep breath and move forward.

It is getting a lot more process-orientated -- and it has to get a lot more process-orientated -- because you're dealing with so many balls you have to juggle in the air. Mocap is really here now, and it's here to stay.

That leads you to make a game in a completely different way because you can't experiment so much with mocap. You've got to have a short list, and if you've got voice talent in your games you can't mess them around and say "Try this line."

We're already mid-process in change, and we've kind of looked at that; we've taken some pretty big steps along that route with what we are working on now. We are taking some fairly big steps on the quality.

But what's so fascinating about it is there's so many things that are increasing in quality. One of the things that really, in my opinion, dramatically increased in quality is the ability of teams to do the most amazing demo. It's like that E3 show-stopper demo. There is a real craft in doing that; there are separate teams that just do an E3 demo or press demo.

I begin to say to myself, "Well, hang on a second. This is a bit like what Hollywood does with trailers, which I absolutely hate." You see a trailer for some action film, and you know you've just seen the best bits of the movie. I think games are starting to go down on that side. The amount of craft that we put into the public perception and the demo and the stage presence of it and the pacing of it is astounding. It's amazing, really, because, of course, that's totally distraction off the game.

Do you think it stops the team from concentrating on the right thing?

PM: Absolutely. In fact, we've always struggled a little bit with that, because I've hated actually doing demos for demos' sake. You have very little time to make a game, and a great press demo for a really important product can suck weeks of time away from the team. Obviously, if you're a well-planned team, you've probably scheduled that into it, but it's incredibly distracting for everybody. So I've always chosen picking up the machine and showing off what we've got, but those are the old days. Those days aren't going to come back.

Especially if you have to put something on Xbox Live for the users to download prior to the release, as well.

PM: That's right. All of these are part of the lead-up event. So often, there's a struggle because you know that you see some demo from us, or from anybody that's a year away from launch, there's no way that that game could be that balanced as the demo suggests.

To that end, you demoed Milo, and there was some back-and-forth on whether it was going to become a product itself. It became more of an R&D effort to increase technology internally. Is that what we sort of arrived at?

PM: I can't say anything about Milo. I've got in such trouble -- an amazing amount of trouble, like standing in the corner of the room and being shouted at sort of trouble. I've always been cheeky in the past, and I've always pushed the boundaries of what publishers would like me to say, but this is literally standing in front of a court and being stripped down repeated times. (Laughs)

The reason that it interests me to an extent -- not what the fate of Milo is -- is that there could probably stand to be more pure research-oriented development, the expectation that everything that developers come up with inside an organization doesn't have to play out as product. Nintendo does a fair bit of that, but it doesn't seem like that's built into a lot of other companies.

PM: Yeah. I do one or two things that we're doing that you might be interested in. I agree with you, by the way, because you end up driving down a dead end if you just make stuff for the game that you're making. At some point, you'll reach a dead end, and then you'll have to go back again; when you go back it's very expensive and incredibly time-consuming.

One of the things that we do at Lionhead -- and I'm thinking of inviting some press along to this -- is we have a creative day where people at Lionhead can show off their ideas, and we give people working on those ideas blocks of time that they can work on them and they can form little mini-teams.

Some of the stuff in Milo came from one of those days -- the object recognition stuff came from that day. We all come together in a whole-day thing. Everyone shows off their project and their idea and what they're working on. Sometimes it's a website, sometimes it's a piece of art, sometimes it's a whole game, and sometimes it's a game mechanic; but I think that it's incredibly healthy to do something like that.

Well, you see that often much more on the tech side with Google and 20 percent time and other companies who are following that lead where you give people some time of their own.

PM: Yeah. Interestingly, I don't actually think that Google's 20 percent time is a reality. I was fascinated in that, and I tried to talk to a few people who'd been in that machine; they said, "Well, actually, it's 20 percent of your time if you've got 20 percent of your time to spare, and not many people have got 20 percent of their time to spare."

What we do, when we thought about that approach, is saying, "Well, just schedule people into it." What we chose to do is say, "Right, this is the defined period of time that you've got. You can ask for more time, but that's going to be the entire focus, rather than saying I've got my day job and this is my night job."

I've already seen some glimpses of what's coming up, and there's some really impressive stuff. Some of it is really cool. I think it'd be lovely to have some people from the press there -- not to do press, so much, although if you did do press it'd be fine; but more to give a press person's perspective on what they're seeing. I think it works best when it's more than just internal people coming.

That was a very clever way of avoiding your very clever question about research!

There's a few things that I think are big-picture questions that you could very much speak to since you've been at Microsoft in the role you've taken on for awhile. I've spoken to different Microsoft people about this, but it very much seems that the 360, particularly -- we're about to enter its sixth holiday season, which would be where we start to say "This is the lifespan of the console," but I don't think that we're even close to that, probably.

PM: I don't think that we're an old enough or mature enough industry to have a regular cycle just yet. This is the second iteration of Xbox. You could look back at the last Xbox and say, "Well, that one lasted five years, so this one must last five years." This is not talking particularly about Microsoft, but I do know, from a developer aspect, it's quite a disturbing thing when you go through a hardware refresh. Part of you is intrinsically excited about it because it's something new to play around with, but you have to take a huge breath; there's an enormous amount of hard work ahead of you.

There's always this bizarre fight around the industry: "Are you going to be a launch title? Oh, you poor soul; you're a launch title," versus "Oh, I'm a launch title; I'm really proud to be a launch title." It's a very upsetting time.

This is me, personally: I don't think we've quite squeezed enough out of our existing tech. I saw Battlefield 3, and it just goes to show that there are still surprises on the visual side; so I don't think there's that pressure yet. It is a big game of bluff, of course: who's going to come first out of the gate will probably be the forcing function for everybody else. The 360 was, of course, the first out of the gate before. It's an exciting time. I agree; five years is quite a long time, but you can see things like Kinect and Move extending the console cycle, just as EyeToy did back in the PlayStation 2 days.

Fable: The Journey

And the teams, as you say, are in the process of refactoring some process-oriented things, and I think very much so, if you look at where people are working. It's still very much a process of learning to work efficiently at the scale.

PM: Yeah! It is, because now the bar you have to reach is so extremely high. It is thousands of pounds a minute, if you think of it that way; if you waste a minute, you've wasted a thousand pounds and wasted an opportunity.

I look at Fable III, and it's hard to be completely honest without offending people; but I know, when I read in the middle of a review that said the quality just wasn't good enough, I actually agree with those reviews.

I think Lionhead can't afford to rest on its laurels of its fans and produce low-quality stuff. We have lots of excuses, as you always do have excuses; but I don't think that's good enough. For consumers, it's very simple: there's a bright light here, and there's an even brighter light there. They're going to go towards the even brighter light -- and why shouldn't they? You just can't sit on your hands and say, "Well, we know how to do it. It's Fable, so that's the way we do it." You just can't do that.

At GDC 2010, you gave a speech about all of the things you were going to bring to Fable III to increase its reach, and you talked about your goal of hitting 5 million units. But it seems that Fable III didn't quite reach the goals that you'd hoped for, at least perhaps creatively.

PM: Yeah. I think last year we were just on the cusp of possibly getting everything we wanted in the game, or possibly having to come down and edit very heavily to finish the game in what was two years. You have to remember that, you know, Lionhead -- especially me -- has never created projects in less than two years. This was the first time we ever did that.

Just after that point, we then sat down, and, partly because of the way that we worked -- the process, the way that we designed, and the way that we crafted -- meant that the game came together very late. That is one of the things that we're changing; that is just such an old school way of working.

You have these ideas called pillars, and then you rush away and develop these pillars. About nine months before the game is due to be finished, you've got to bring that whole thing together and then -- "Oh, wow! The game's this long!"

Every game, unbelievably, you sit down: "Good grief! It's twice as long as I thought it was going to be!" You just can't afford that in terms of development when you're developing by the second.

So when we came down to it, the edit -- I think the ruling section in Fable was the one that really suffered a lot here. The edit was very harsh and hard to actually make the game fit.

That being said, I still think it was a good game! I just don't think it was a great game that took us to 5 million units. I know I probably should say it's a great game just respective of whatever it was, but the Metacritic score was sort of low-'80s. I think I'm pretty ashamed of that, to be honest, and I take that on my own shoulders, not the team's shoulders. I think that, when you have something like that, which you can feel as a kick in the teeth, you have to pick yourself up and fight even harder.

That being said, it still sold millions and millions of units, and it's probably going to net out, with the PC version, closer to the 5 million than perhaps you would think; but it's not the dream. It didn't end up being the game that I dreamed it would be, because I thought the mechanic of the ruling section were really good ideas. I thought they were good ideas, but we just didn't have time to exploit those ideas fully.

I've been here before, and it just means that you've got to make whatever you do next twice as good. You're going to make the process and the planning process much, much better because, in the end, that's where you really suffer.

So you're chasing a moving target.

PM: Yeah, you're chasing a moving target. God, it would be so lovely to talk about an example here, but I can't; but I think there are some very, very obvious things that you should do if you're a studio like Lionhead -- very simple and obvious things.

I'm not breaking the confidentiality by saying this: you've got to look at the quality of what you make, and you've got to ask yourself, in all honesty, "Is it good enough?" Or should you be doubling down and saying, "We're really going to surprise people with the quality of what we make"?

You should say that about the uniqueness of what you're making, as well. I hate the fact that people know what to expect from something like Lionhead. "We know what Fable's going to be; we know what's coming next from Lionhead." I hate that idea. We should, again, double down on freshness and originality without sacrificing -- because often originality can sacrifice quality -- without sacrificing quality.

We should take a deep look at what people really enjoy about the experiences that might have made and try and focus on those rather than focus on the gimmicks, which we kind of love to develop. That is being a little bit self-critical, but I think that there's times that you have to be self-critical. I think the worst thing that could have happened to Fable III is if it sold 4.99 million, because I think that would have made us slightly complacent, and complacency is always the worst place to be, in my opinion.

In particular, something that interests me about Fable is that you talked about things like making leveling and taking it from an abstract into the way your character develops. Moving things out of the GUI and putting them into the game concretely, thinking that would make the game more comprehensible. How did you find the reaction people had to those sorts of changes?

PM: This is absolutely an example of everything I just said. So just take that example. I thought the idea of leveling outside the GUI, but leveling in the environment and the world was actually quite a good one, but I'm not sure...

The real dream of that leveling process was that, as you went through each gate, there would be these tough choices for the player. Which chest should I open? This one or that one? The feeling that you're going through the game at your own pace, but having to make these tough choices, was never actually realized.

This is another thing where the process of us doing the game -- the game came together so late that we had so little time to balance and refine what those chests meant and the leveling-up implications of it; there was just a few weeks to do it. That meant that what could have been a great mechanic turned out to be a good idea.

I don't think that good ideas are a reason to do something; I think it has to feed into the overall experience to be a great idea. I liked the idea of not pressing the pause key and going to some abstracted GUI; I think that worked reasonably well, and people didn't argue about it.

The dream was that there would be an intelligence about that place, which was led by the John Cleese character, which made it feel really alive; and again we didn't have the time to craft that into what that dream was.

It's because of those things that, now, when we approach development, it's very different, because we want to know precisely how long the experience we're crafting is up front, rather than waiting to the end, so that we have a clear idea how each of these mechanics is used, how they're meted out, how they're exploited, and how they're really used to amplify the whole drama of what that is.

So we've got a very, very different process of designing now, which means that, this time around, if we did have a Journey to Rule or if we did have -- I'm not saying that I'm giving you any clues there -- then it's going to be part of that golden thread that we're making up to the player. We've spent a long time thinking about that and doing our research on how you can have a creatively-led production process and how you can take the complete randomness out of the way that a lot of ideas are developed and evolved.

Read more about:

FeaturesAbout the Author(s)

You May Also Like

.jpeg?width=700&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)