Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Gamasutra talks extensively to Insomniac CEO Ted Price, following Resistance 2's launch, discussing the company's history, relationship with Sony, development methodology, and much more.

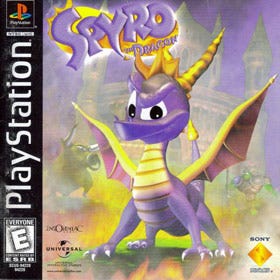

In 1994, developer Insomniac Games, nowadays best known for creating franchises like Spyro, Ratchet & Clank, and Resistance, was founded by a group including Ted Price, CEO, president, and creative director at the company.

Since that time, the developer has forged a reputation for quality, and has concentrated exclusively on its relationship with Sony platforms and Sony itself -- having not published a game with any other publisher since 1996's Disruptor.

In these unique circumstances, Insomniac staffers have been very vocal about the core philosophies that drive the production of games at the studio -- per the developer's website, "quality over quantity", "innovation", "collaboration", "efficiency", and "independence".

Gamasutra recently spoke to Ted Price at last week's community event, held at the company's Burbank, California headquarters.

You'll find below a wide-ranging discussion about such topics as Insomniac's decision-making process, its development cycles, its new studio in North Carolina, and the company's relationship with its fans.

You presented a lot of interesting stuff today, but one thing I can see is that it seems like you're really into this idea of having this community day here; you seem really charged up by having the fans here, having a chance to talk to them, and just to give back. Can you talk about that a little bit?

Ted Price: Community is something that we started years ago, when we went into the multiplayer space, and as we have released more and more games with multiplayer component, we've learned more and more that community is essential to supporting an online game.

And the MyResistance.Net community, and the Insomniac community have been instrumental in giving us feedback about what's good about our games, and what's bad about our games.

So we wanted to make sure that our community recognizes how much we appreciate their feedback. And it's unfortunate that we can't bring everybody from the forums to Insomniac, but we did our best to bring in people who could actually make it, and who we knew would enjoy getting kind-of a peek into the game development process.

You could tell how enthused everyone was to be here. They were just totally pumped.

TP: Yeah. This is what we live for, because it really is direct contact with people who are playing our game for fun. Not necessarily because they're doing a review or looking at it for competitive analysis; they're just out there because they love games. So...

I was actually a little surprised; you pulled back the curtain a little bit more than I expected, actually. You were pretty frank about some of the decisions that you made, and some of the tech, and also just showing the test environments and stuff. I was actually a little surprised how open you were -- but I don't think it's going to hurt, at all.

TP: We're not concerned about talking about the development process. In fact, we have an R&D section of our website, where we give away a lot of our, if you want to call them quote-unquote "trade secrets."

TP: We're not concerned about talking about the development process. In fact, we have an R&D section of our website, where we give away a lot of our, if you want to call them quote-unquote "trade secrets."

And the idea is that, in this industry, things move so quickly that there really aren't that many trade secrets -- things that get you ahead -- necessarily.

It's more about your production process; it's more about being efficient, and continuing to push your design. So we want to give back to both the community, and to the industry, with what we do with our web page, our community day, and with our [code and game development solution-sharing] Nocturnal Initiative.

And you guys are pretty keyed into participating in industry events, as well -- I mean DICE and GDC, and stuff. Which is really useful, I think, from you guys, because you guys are such evangelists about having your tech in-house; pulling it all in and doing original tech.

TP: It's something that we started with 15 years ago, and it's always -- it simply colored the way we develop games. We made that decision early on, and as a result, we develop a certain way. And for us, we place a lot of value on being able to control one's own tech, and customize it for the games that we're doing.

In what way do you think that is shapes the way you develop your games?

TP: Well, that's a good question. It's hard to compare how it colors our development process, to how people who use off-the-shelf technology may change their development process, but...

When we begin developing our games, we know that we can propose design ideas that we might not be able to support at the time. And when we do that, we go to the tech and tools team, and we ask the guys, "Can we do this?"

And on a lot of the occasions, the answer is yes; on some instances, the answer is no, but there is always the chance to dream big, because we can implement new tech during the production cycle.

I was just talking to Jake [Biegel, co-op lead designer], and he used the analogy that there are three core modes in Resistance 2. There's the multiplayer, co-op, and the single-player campaign. He used the analogy that it's sort of like The Orange Box, in a sense that they stand very strong on their own -- there's parts that are completely original that don't touch on the other parts of the game.

TP: There's community, as well, so that's kind of the fourth piece, yeah.

So what do you think about this, you know, building a game with such strong components, wrapping it all under Resistance, offering as much as you can?

TP: Well, our goal was to create components that can stand on their own, but were also hooked together by the overall theme. And, certainly, I think we achieved the first, where all of the components do stand well on their own.

As far as how well they hook together into the game? I think we did a good job; I think we learned a lot about how we can perhaps in the future do an even better job of making all the parts fit even more tightly together.

For example, the co-op story is the story of a separate Sentinel team; it's not the story of [protagonist, Nathan] Hale. And people asked us, "Why didn't you do the story of Nathan Hale? Why didn't you do his story?" And the answer was: Well, practically, it didn't make a whole lot of sense. Hale has his own story through the campaign, and so we didn't have much of a choice, we needed to do a separate story for the co-op campaign.

In the future, we may figure out ways to bring those modes even closer together. I think, on the other hand, a lot of people appreciate the fact that these are three separate modes, so, in some cases, it does feel like you are playing a separate game, and it is three different experiences, which adds a lot of replay value to the game.

Talking to someone I've spoken to who was heavily involved with the beta, they talked about how, at least personally, they were "meh" on the campaign, but they really enjoyed the co-op. To them, seeing it as a separate entity gave them a window into enjoying the game in the long term, that they may not have had if it was just playing through the campaign but with two people. So, there's something to be said for having different approaches.

TP: Yeah. And I think that we have people who definitely appreciate how different the co-op campaign was. On the other hand, we're seeing plenty of posts from people who ask, "So why didn't you have co-op move through the single player campaign?"

And, the answer is, well, we made a choice, and we couldn't do everything, and we also wanted to make the single player campaign a very strong single player experience.

And, we learned, on Resistance: Fall of Man, that the single player campaign can be diluted a bit if you try to create a co-op playthrough. There are certain things that you simply can't do. For example, the bosses that we had in Resistance 2 would've been tough to pull off with two players.

And if you look at the way Epic approaches it, with Gears of War, they made it so that whether or not you're playing with somebody else, Dom's always there. So, that was their concession, you know what I mean? I'm not saying that theirs is right or yours is right; they're both right.

TP: Well, as a matter of fact, we looked at the way that Gears did it, and realized that, yeah, we would have to have a Sentinel with you the entire time, through the single player campaign.

For the single player campaign, we wanted both experiences, when you're playing with a couple Sentinels, all of the Sentinels, and by yourself, just to vary the gameplay. And so, that was the choice we made; was to go with eight players in a separate campaign. It worked out well.

I mean, the one thing I thought is, "God, eight players! That's really, really hardcore." I know that shooters are a core genre, and this game is going to have a large, passionate fan base of the hardest-core PS3 gamers, but, at the same time, getting eight guys together, to play the game at the same time -- and I realize that it drops down all the way to two, but still that's a relatively serious commitment, I think.

TP: Well, you don't have to gather them yourself; our matchmaking system will match you into games, if you are interested in just going online and finding a game. You don't have to have a party. But, the cool thing is, you have a choice: If you want to grab seven of your friends, then cool.

Did you guys do any research into behavior? I still think that a little bit of the behavior online is still a little bit of a "black box" for developers. This "online revolution" in consoles is still relatively recent. Xbox 360's been a few years; PS3's been two years; there are still a lot of unknowns there...

TP: There are. We're still learning what players want online, and what the "typical" behaviors are. But, it's evolving quickly, and I don't think that we can ever look at a particular online behavior and say that's typical. It's just, lots of people want to play lots of different ways, and we try to make games that will accommodate as many of them as possible.

But I think our community helps us out in a big way, because that is our direct access to the people who are playing games. We can get their opinions on what they want, very quickly, versus having to go into a game and listen to the chatter.

We're seeing those posts on the forums; they're emailing us, or sending us PMs and saying, "Hey, Insomniac, we want X, Y, and Z." And so, we can discuss those requests and decide whether or not to change the game around the next time, or include new features in our patches, etcetera.

It's clear from the presentations today, and also from talking to [community head] Ryan [Schneider] earlier, that you guys think that the feedback from the community is invaluable, in terms of shaping how the game could evolve.

TP: It certainly shaped how R2 evolved. I mean, the proof is there with many of the changes we made in Resistance 2. And whether or not everybody likes the changes we made, many of them were motivated by the community.

We all know that the people who participate in the forum, and set up their MyResistance profile, and everything, are going to be the biggest fans of the game. Do you ever mitigate, or temper what you get out of them, with different, other research, or just your own ideas about what will appeal to the guy who just goes into Best Buy, who goes, like, "Dude! Aliens!"?

TP: Yeah, as a matter of fact, we did research; we did a study on Resistance: Fall of Man, and it was done by a group called Chatter, and it was a very blunt assessment of Resistance: Fall of Man.

It was probably the most critical assessment I've seen of any of our games, and it was the best thing that we had ever read, because it called out, specifically, what was wrong with the game, and what the game was missing. We've addressed a lot of those issues a lot of Resistance 2.

I mean, for example: Hale. One of the main complaints that the study brought up was that Hale was just basically non-existent in the story for Resistance: Fall of Man, and the narration made it very difficult to identify with him. And so, when we saw that, we reinforced our attempts to bring the story back to Hale, and tell it from his perspective, and develop him more. And he does: now, in Resistance 2, he changes throughout the game, and he has a more complex relationship with the others in the game.

Was that already your instinct for the direction of the game?

TP: Well, we'd heard some of that from players, but on the other hand, we'd heard from people who also liked the narrative approach. But seeing this from an outside, objective source, really helped push us in the direction.

Another thing we heard from the study was that Resistance: Fall of Man didn't have as much of an identity, because of its setting. And people weren't quite clear if it was taking place in the '50s, or the '60s, or even what country it was set in.

And so, we made a much bigger effort in Resistance 2, to push that feeling of 1950s America. And one of the results of that was a Henry Stillman broadcast that you hear throughout the game, and other aspects that really play up the kind-of quote-unquote "American" feel.

You also asked if there were other sources that we looked at besides our own forum. And we go to places like NeoGAF, for example.

(laughs)

TP: And NeoGAF... What's your opinion on that?

Trust me, I read NeoGAF too, and I mean, I periodically go on the 1UP podcast, so I have my own run-ins with NeoGAF, and post on NeoGAF a little bit, so... I'm just laughing, because I'm imagining when NeoGAF finds this interview, what the reaction is going to be to hearing themselves called out by Ted Price.

TP: Well, we really enjoy it. I mean, those guys are not shy about sharing their opinions, and it's always fun to read through the posts, when it comes to our games or anything we do. It's a good counterbalance to what we're seeing on our own forums.

Do you find that different communities online have different reactions? Like, the tenor of your community, and its reactions to your game, is different from what you see on NeoGAF, or what you see elsewhere, on maybe blog comments on Kotaku, or anywhere?

TP: Well, sure, Kotaku is a good source. IGN, also, the IGN forum is a good place to go as well. What we see are probably a more diverse group of folks who, perhaps, are into Xbox 360, or other games, who are commenting on our games, and... it's always entertaining.

I thought some of the questions from the community during the presentation were impressive -- they're really plugged in, aren't they?

TP: I was impressed. I mean, they're well-educated, on the games, on what we do, and on just the industry in general. So they were smart questions.

Insomniac's Ratchet & Clank Future: Quest for Booty

Yeah, they were savvy. One person talked about how you guys ship a game a year -- which, I guess, you've shipped like one a and a half this year, because you have Quest for Booty. And you talked about how you now have the alternating cycles, and you moved to having a year for prototyping, for games now. Your typical cycle is a 24 month cycle, now?

TP: It's 24 months right now. Yeah. We have a preproduction team starting on a new game.

Is that a small, core team?

TP: Yes, usually it is a team of people who prefer to stay -- who have a common interest, whether it's the franchise that they're staying on, or a new IP that we're working on.

And they are a group of folks who have a diverse set of specialties, who can help form the core of a new game. So, gameplay programmer, designer, artist, concept artist, animator, can all get together and begin to lay the groundwork for the game before the rest of the team comes on.

How long would it be with just the small core group?

TP: It varies depending on the game we're doing. For Resistance 2, we had a programmer-heavy group working for probably six or seven months to redo a lot of our systems that we initially created for Resistance: Fall of Man.

They brought them up to date while a couple of designers were working on prototyping new weapons, and coming up with ideas for the new forms of gameplay.

At the same time, what's become a little bit more complex is our multiplayer team, who is also doing double-duty at looking what we're going to be doing for our next game, and also fixing bugs and putting out patches.

You used the phrase "double-duty", so do you have a live team, but they are also forward-looking at the same time?

TP: Exactly. Yeah.

Sounds tough.

TP: Well, it is, but it's not as difficult as putting the game out. Because after we've released the game, the game is generally working very well, and the bugs that we're fixing are very minor, or they're making tuning fixes based on what we're seeing from the community.

One thing that we had sort of touched on -- and this has come up other times -- is encouraging the behavior of the gamers through the design, and, particularly with the multiplayer, with the class system and the squad system, encouraging the way people stick together, and play the game.

Designing multiplayer has got to be a big challenge; when you're talking about the numbers, eight for co-op is a big number, and 60 for competitive multiplayer is a ridiculous number, so... Has that been a real challenge?

TP: Well, when we began designing for Resistance 2 on the multiplayer side, we experimented with a lot of ideas. And Skirmish evolved from a lot of experiments that didn't quite work. We ended up kind-of having a "eureka!" moment at one point with the Skirmish mode, when we were faced with the unfortunate reality that just putting 60 players in a big arena doesn't work. It's just not fun!

And so, the design and multiplayer programming team got together and just figured out how to make the dynamic objective system and the squads work well. But it was a painful process, for sure, and we went through many iterations to actually get it right.

But I've got to tell you, those guys, kudos to the design team for both co-op and multiplayer. And the multiplayer team, the gameplay programming team which participates as much in design as they do in programming.

Insomniac's Resistance 2

One thing I really definitely got an impression of from talking to people, from listening to the discussions today, and the panels and stuff, is that this is a highly collaborative company; that you encourage that at all levels, and that people can contribute to the games in multiple ways.

TP: To me, after almost 15 years of doing this, it's weird thinking about how it could be any other way. We just have so many people here who have come to Insomniac because they want to make games -- and they want to make fun games. It would suck to stifle that creativity.

There is a certain point, though, I imagine -- well, no, I know -- where you have to buckle down and you have to say "This is what's happening."

TP: Of course.

I mean, this sounds really autocratic; it's not what I mean. But there's a point where you say, "OK, now go back, and it's your job now to program that, or it's your job to go crank on the assets," or whatever.

TP: Well, that's why we do have deadlines, and why we do have a hierarchical structure, where, ultimately, the creative director makes the final call on what's going into the game. But what has, for me, been fun, is that most of the decisions are made before I have to step in and say, "Well, OK guys, I'm going to break this tie by voting this way."

With enough discussion -- because we do encourage a lot of discussions and arguments here -- the best ideas usually fall through to the game. That way people walk away, even if they originally proposed a different idea, agreeing on what is implemented. And there tends to be a lot less friction that way.

Getting to that point, getting to that point usually is the result of many heated discussions. There have been a few shouting matches over various aspects of the game, but my goal is to make sure that people walk away feeling like we achieved a great consensus.

Something that you said this morning is that you "build consensus".

TP: I mean, that's what I feel like my job has been in general, whether I'm CEO, or CD; playing CEO today, or playing CD today, it's trying to encourage people to put ideas on the table that are either going to make our games better, or make the company better.

And then, discussing them, and walking away with an agreement between the people who are passionate about whatever idea happens to be in discussion.

I mean, I do end up making a lot of decisions in the role I'm in, but I like making decisions that I feel are supported by the company; otherwise, why would anybody want to work at Insomniac, if you have a leader who is just going against the grain all the time?

Right.

TP: I believe heavily that you have to have strong leaders on projects; you have to have somebody who's willing to stand up and make the tough decisions. And creative directors and project managers at Insomniac end up making decisions all the time.

That may not be popular, but there's a lot of discussion that occurs before those decisions are made; we do not encourage going off and just making off-the-cuff decisions, because that can result in tears.

It's a balance that has to be struck, no doubt. Development is a series of compromises, whether it's technical compromises, or how much time, how much money, how many people you have to produce how much assets, how many levels, whatever.

TP: And there's, also, there's a balance between getting just stuck in analysis paralysis, too, where you could be discussing an idea forever, and you've never made any forward progress, and all the sudden you've missed your deadline.

So, at Insomniac, we are extremely deadline focused, and so we know that there is a time for discussion, and then there's a time for action; and I think we delineate between those times pretty well.

Are you guys still really heavily milestone-focused?

TP: Very.

So you guys are really traditional. Because there's a lot of discussion about -- at this point it's moved from people moving to Scrum, to people picking apart Scrum and throwing away the bits they don't like, and mutating it and stuff.

TP: I don't even know -- I mean, I could not define what Scrum is for you. I've never read anything about it, I don't know much about agile; I just know how we do it at Insomniac.

And that's probably a very narrow view, but it's worked for us, and we've managed to release triple-A titles consistently, every year.

So, I guess it's fun to hear about what the rest of the world's doing, and we can learn a lot, but we have people coming in from outside all the time, joining Insomniac, who bring their experiences, and help add to what we call "The Insomniac Way."

I see. And one thing I wanted to talk about, to get more general -- this comes up a lot, no doubt, and I don't want you to think think that I'm really fishing around, here, but you guys, at this point, I don't want to speak wrong -- but have you ever had a game that wasn't published by Sony?

TP: Yeah. Disruptor.

Disruptor. OK, that's what I thought...

TP: And in fact, Spyro the Dragon -- that was actually quote-unquote "published" by Universal Studios, and Universal sub-licensed the rights to Spyro to Sony.

TP: And in fact, Spyro the Dragon -- that was actually quote-unquote "published" by Universal Studios, and Universal sub-licensed the rights to Spyro to Sony.

And had it not been for that occurrence, we probably wouldn't be around, because Sony marketed the hell out of that game, and made it a household name.

But, for the last ten years or so, we have been working very closely with Sony. And, I know what you're getting at -- I mean, people ask me all the time, "So, do you consider going multiplatform? What are the drawbacks?"

There are questions, right? One obvious thing is, I would say, it's atypical for an independent developer to stick with one publisher almost exclusively for a decade. That's for sure.

TP: Yeah. Well, I mean, there are certainly benefits and there are drawbacks to it. The benefits are that our games tend to be associated with the hardware -- but that could be a drawback, too.

So, with Resistance: Fall of Man, because we were a launch title, we did get a lot of additional exposure simply because it was synonymous with the PlayStation 3. And it's hard to break into the genre; and it's cool that we were able to do it with a brand new entry.

Let me put it this way -- and, you're free to respond however you want -- my inference would be that if you had wanted to be acquired, by now you would have been. But you have not been.

TP: Absolutely. We definitely have been very vocal about maintaining our independence, and there's -- personally, for me? I really enjoy what I do, and I don't like being told by other people what to do; and I think a lot of people at Insomniac feel exactly the same way.

And a lot of people at Insomniac have come from other shops, where either they've been a part of a publisher, or they've been at a developer owned by a publisher, and they've told me that it can be frustrating to have a publisher acting with a heavy hand.

Our relationship with Sony is one where we develop autonomously. Sony certainly gives us great feedback on the games, but we're in control of the development process, and that is a great place to be. Especially with a partner as powerful as Sony.

Like you said, it does raise your profile, and certainly, Sony is going to market the hell out of your games, because they're high-quality and exclusive.

TP: But, then again, we see the other side too. We see games that are multiplatform succeeding wildly, and doing great, and that too is a fantastic place to be.

Something that you did last generation, that I'm not aware whether you are in this generation, and you may or may not be talking about it, but you guys did tech sharing with Naughty Dog last time, right?

TP: Yeah, we definitely went back and forthwith them on various aspects of engine technology, and some other technology.

Is that something that's not continuing? Is that just because you're working in different genres, or is that because, just, it naturally fell away?

TP: That's a good question. We have certainly compared notes with Naughty Dog; we just haven't been sharing any code. The engine we created for the PlayStation 3 is fully Insomniac's proprietary engine, and it was also on PlayStation 2.

Unfortunately, what's frustrating sometimes is, people still say, "Oh, isn't that using Naughty Dog's engine?" And the fact is, that wasn't the case on PlayStation 2, and it isn't the case now. But, our engineers do talk frequently, because we share similar challenges, and we can both learn a lot from each other.

And that's great, and that's what we like in this industry, is that people are open about what they're doing, and we all benefit when we share information. And that's, again, one of the reasons we started the Nocturnal Initiative: So we could put some of our code out there, have people check it out, make suggestions, make changes, and then we can reincorporate it -- and vice versa. Everybody wins when you share code.

I'm familiar with it in a very general way, and I've been to the site and poked around a little bit, but is that essentially an open source thing?

TP: Yeah. It's open-sourcing some of our tools; that's correct.

That's an interesting thing to see, especially on closed platforms.

TP: You know, we win too when there are better and better games on the PlayStation 3. I mean, because currently we are developing all of our current games on the PlayStation 3, we want that platform to succeed, so, hey, we're going to do what we can to help other developers too.

And I guess the final thing that I want to talk about before I let you go, because I know that you're a busy guy: I want to talk about Insomniac North Carolina. How long has that been established, now?

TP: Well, we announced it earlier this year -- probably five months ago? I think there are ten guys out there now. Chad Dezem is our studio director; Shaun McCabe is our production director; they have opened up the studio officially, and are moving into the offices, and getting everything ready to move into its first production cycle.

What attracted you, initially, to opening a studio in a remote location?

TP: I wouldn't call it remote.

Well, it's 3,000 miles away.

TP: Well, yeah, remote from us; it's a great place, though, to have a game company. I mean, the Raleigh-Durham area is filled with fantastic development companies, and it's a very friendly community, as we found when we announced that we were going in.

As soon as we announced it, we got calls from guys like Epic, and Red Storm, and lots of other studios just welcoming us and saying, "Hey! We're looking forward to having you be part of the community!" I talked to Mike Capps about it, and Cliff [Bleszinski], and we all know each other well, and it's really cool to know that we're neighbors with some of the best developers in the world, out there.

And what led you to choose that particular geographical location?

TP: Shaun and Chad had expressed an interest to move back east, but at the same time, they wanted to remain a part of Insomniac. And the reasons they wanted to move back were for family reasons, and I completely understand that. And there are other people here at Insomniac that have family back east, and would prefer to be on the east coast, so that was a slam dunk.

At the same time, here, as we continue to produce more and more games, the pressure to expand continues to increase -- but we don't want to have a monster company here in Burbank.

And so, being able to support a sister company, another branch in North Carolina, is a great way to expand Insomniac but keep that intimate feel that we've cultivated over the years.

So you think that it's going to retain the broad Insomniac culture, but maybe develop its own sort of culture at the same time?

TP: Sure. Yeah, sure. I mean, I think that both Chad and Shaun believe in the Insomniac philosophy that we have used to develop games over the years, and I'm looking forward to the North Carolina studio bringing new aspects to what we do here in Burbank.

So I think that'll be a great back-and-forth. And we're also going to be supporting the North Carolina studio with tools and technology that's built here in Burbank.

Right, of course.

TP: So, it'll be a very close relationship.

Do you have a core tech team? Or does the tech just grow out from the development of the games?

TP: We do have a core tech team; we have a core tech and tools team. So, we have a number of extremely talented engineers on both teams, who are both developing new tech for the PlayStation 3, and tools, proprietary tools, that we use to build our games.

Is the North Carolina group, are they just starting out? Are they in preproduction?

TP: Yeah.

And they're going to be recruiting, and then move into production in a time frame that you're not, probably, going to talk about.

TP: That's right.

(laughs)

TP: But they are recruiting right now, so we are still looking for folks. But it's great; we've been adding a lot of folks. Which brings up another reason we started the studio: We know that there are a lot of very talented folks on the east coast who are looking to join, to get into the development field.

And when we talk to people on the east coast, they don't necessarily want to make the switch to the west coast, and so, this is an opportunity for them to join Insomniac.

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like