New Business Models = Demise of Publishers? Really?!

This article analyse case studies from three studios gone to the developer graveyard and pays particular attention to their relationship (or lack of) with publishers.

So the topic from the previous fortnight for my marketplace research was innovation and the illusions of stability in the industry. We had a range of reading sources to bury our heads in and were then presented with three questions, which we had to select one from and attempt to answer in within two/three minutes of speaking. I chose a question which suggested that new funding options for developers would eventually eradicate the need for publishers. Though my response was initially an array of bullet points shelling my overall argument, I write this in an effort to flesh it out.

To begin, I felt it best to give some back drop to why new models are required at all, and what challenges have forced the hands of developers. I also give three examples of failed studios that could have done with more business sense (which publishers bring to the table). So we find ourselves in a recession that came into effect in 2007 (apparently we rose out of it, but then fell inevitably back into it). This has affected every industry regardless of it's provisions or it's products. Despite the initial belief that the games industry was recession proof, it too has faced the crunch.

Whilst this article isn't about the damage done by the recession, a vague framing of it helps to understand the drive to create new ways of prising the precious coins from the consumer's grubby mitts. I believe such a complex system requires more thought than to assume the changes occurring are simply borne of desperation though. There is a love hate relationship between publisher and developer, one which is generally hate from the developer's perspective. Steve Ellis lamented the interference of Ubisoft when they took over publishing for Haze, contrasting against Free Radical's previous publisher Eidos and it's passive demeanour with regards to the Timesplitters 1 and 2 production cycles. It's worth noting that this change in focus of publishers wasn't specific to a single case, and that publishers took more of an interest in providing the consumer with what they wanted mixed with what would make for a viral mass market experience for players of various demographics rather than just one.

Games became extremely expensive to build as technology improved, so it was only natural that the financiers would demand that the features of the production were tailored to a wider audience in the hopes of making a profit. Despite this, developers are always striving to work independently of external publishers in order to have a closer relationship with the end users and retain the majority share of their IPs. The majority of self published titles are created with much smaller budgets than the Behemoth triple A titles.

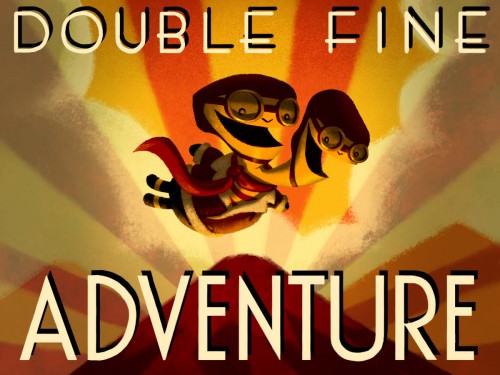

For example, Tim Shafer and Double Fine with Adventure used 'crowd-funding' to raise $400,000 dollars (and ended up with over $3 million) in order to bypass the publisher after his bitterness with Brutal Legends confused launch campaign. Self-publishing favours smaller, less technologically ambitious projects that require little time consuming R&D. The indie genre, for example is mostly made up of self published titles (at least to begin with before they are noticed by a publisher that wants to sell millions of it). We can also place some emphasis on change at the doors of fresher entrants into the industry.

Relatively new players to the market are social networking games with evil corporations like Zynga squeezing the life out of browser games. Free-to-play titles are amassing in vast numbers hoping to coax players into seeing the benefits of buying play changing goodies and subscription titles like the once invincible World of Warcraft are heading towards hard times with a drop in over 1 million subscribers with the space of a year. Whatever the reasons may be, new models are developed with the sole intention of maximising profits and make the cost of development a bit easier to manage. There are pros and cons of publish and se-publish methods and we will touch on those with the case studies.

So first up comes the fall of Free Radical Design. Steve Ellis goes into great detail in his article on Games Industry International about the collapse of the company and all of the factors that lead up to it. Haze was the title accredited with its downfall, but there was publisher relationships to consider when painting the line clearly. So as aforementioned, FRD's relationship with Eidos, their first publisher was relatively easy, in that they didn't require a slice of the Timesplitters pie, or even request to see the games until they were given to the QA testers. This agreement of publisher remaining in the background as an investor that had both confidence and trust in their ability to complete and sell a decent title came to an end, and with the heightened costs of creating brand new technology and a bigger title, they were forced to give away some of the ownership of the IP to Ubisoft.

Now this partnership was the example of a bad match. Ubi were intent on getting actively involved in the production pipeline, attempting to make it more efficient with the use of metrics, something of a norm by today's standards. Ellis states, 'they were very much involved in the day-to-day running of things and the decisions that were made, in a really weird and indirect way'. In this example, Free Radical were not ready for moving into what became the traditional model of game development management, and they sorely suffered for it. When concerning Ubi's formulaic method of fine tuning the gaming experience, Ellis put it, 'trying to impose that on an external studio is a difficult thing when you're used to working in a completely different way. Trying to impose it on a team that doesn't all agree with it and buy into it is a recipe for disaster', but at the time when this was happening, we were moving into the current generation of console, and we have all seen the level of competition out there for gaming experiences, experiences that have all been finely tuned with the use of user data in some shape or form.

Further publisher troubles came when they dealt with Lucas Arts. Initially the relationship was favourable with them speculatively working on Star Wars Battlefront III on top of a strong relationship for Ellis & Co, and Peter Hirschman and Jim Ward, both high executives in the publishing house. It fell apart when the two of them were replaced by new management that began axing what could only be considered as financial liabilities. 'The really good relationship that we'd always had suddenly didn't exists anymore. They brought in new people to replace them and all of a sudden we were failing milestones [...], payments were being delayed and that kind of thing.'

The second company to die a painful death in this article is Real Time Worlds. The studio that managed to burn through $100 million and create an open world MMO that went live for 86 days, tanked massively and dragged the company down with it (of which I am of course referring to APB). This is an example of a project that was managed badly and suffered heavily from a lack of a business strategy and a solid financial model.

On a RockPaperShotgun article detailing the laying off of Project MyWorld staff, a comment written by a source known only as 'ExRTW' wrote extensively about the internal concerns about APB and the operating practices of David Jones, and it somewhat opens the mind to why it all fell apart. ExRTW writes, 'The sheer time spent and money it took to make APB is really a product of fairly directionless creative leadership [...]. [Dave Jones is] a big believer in letting the details emerge along the way, rather than being planned out beyond even a rudimentary form'.

Furthermore, in Nicholas Lovell's post-mortem of RTW's downfall, he writes that the the lacklustre approach to strategy by David Jones was misplaced in such a high cost production, and that the Try-fail-iterate model only works on productions of $1 million or less, and when the product is released early, to give it time to grow and improve in a live environment where the consumer play tests it.

So in this case, we can consider the lack of a publisher to be the downfall of the project, as such a demanding entity would ensure company focus, and would chase progress to the point of a game that would most likely be smaller in scope, but almost certainly more successful.

The third example is 38 Studios, you know the same studio that screwed over all of it's employees, saw the last days of Big Huge Games when it was consumed by extreme expectations in the sales department, and found its leadership in an ex-baseball player that didn't have the sense to listen to those in a better position to know their industry, and didn't have the kahunas to admit to the staff that shit had proverbially hit the fan and proceeded to decorate every asset in the office.

Yeah Curt Schilling really did a number on a good 200+ people in one fell swoop. If you wish to check out the sheer scale of fuck-up-ery, then read this very detailed account on Boston Magazine. But the alarm bells were ringing well before it all fell apart, and Shillings excessive "can-do, will-do" attitude made him ignore the fact that he couldn't find buyers because it was a hideous risk to invest in a project (Copernicus) created by an unproven studio. I mean above most of the other silly decisions made in an effort to get the game off the ground, Schilling borrowed $75 million from the Rhode Island government, and relocated the studio to the same place, shifting families promising to pay for all of the costs (the most horrifying bit a mon avis).

Whilst much of the problem lay with short-sightedness, and Schilling could eventually be excused for that (after he was rinsed for every penny that his staff lost to his Holy Grail quest), the added insult of not having the bottle to be transparent with the team when the situation was finally dire enough for him to acknowledge that 38 and consequently Big Huge Games were going under.

The point to all of this (apart from expressing my distaste of this 'strategy') is to point out that the presence of a publisher would have made steps to correct this mistake, and would definitely not have continued the reckless borrowing and spending that Shilling was willing to commit to. Whilst the product itself might have never seen the light of day if a publisher were present, the trade off for the release of Kingdoms of Amalur is that a vast amount of people found themselves stranded and jobless in Rhode Island with rent due, many with mortgages to pay off back home (which Shilling failed to finance in the end) and more so with mouths to feed other than their own. Some of the stories are simply disgraceful.

Some might argue that with modern availability of development kits (most of which have free versions) and even the interesting development of the Ouyo game console funded with the controversial Kickstarter model, encourages an imminent congestion of games, of which quality is not assured. If we consider the Android and Apple app stores for example, even Valve's Steam to an extent, we see countless titles thrown into our every orifice to the point that we cannot find the needle in the haystack.

This is one of the tasks that a publisher contributes to. The work hard to get a game noticed by the press and the public, understanding that their own profit depends on global awareness. Sure their motivations are selfish, and they don't always have the consumer's desires, or the developer's needs at heart, but they are usually very good at sniffing out the good routes to commercial visibility. Self-published titles have to fend for themselves in a market full of mediocre clones and forgettable experiences.

Moreover, publishers request extortionate fees and royalties when signing with developers, yet developers still use them. They serve a purpose and hold a very valid place in the games industry food chain. The market has become more complex with the constant arrival of new funding options and developers willing to risk self-funding, but, if for nothing else, publisher will always be necessary to carry mega triple A titles, like Ubisoft with Assassin's Creed. While they are technically self-published, they are a publishing company as much as a development studio.

The issues that publishers will inevitably face in the years to come will lie with their ability to adopt new strategies when marketing, and present developers with reasons to sign with them. This means venturing into the unknown with new business models as well as new platforms (including the likes of Ouya). It will be more a margin of which publishers survive and adapt, and those which stagnate and die off..

Read more about:

BlogsAbout the Author(s)

You May Also Like