Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Getting your game in front of fans is both increasingly possible thanks to the events springing up around the globe -- but should even indie developers run real-life promotions? UK indie developer Mode 7 Games details a real-life example.

[Getting your game in front of fans is both increasingly possible thanks to the events springing up around the globe -- but should even indie developers run real-life promotions? UK indie developer Mode 7 Games details a real-life example.]

Indie game marketers should constantly be looking around for inspiration. As well as coming up with original means to promote your game, you should also pay attention to the huge range of ideas being generated by more established developers and publishers. Some activities will be completely impractical, but some can be scaled down to indie size for an impact more commensurate with your aims.

Our marketing strategy for Mode 7 Games' PC indie tactical strategy game Frozen Synapse has centered on trying to get quality information out as early as possible during development: we wanted to let people in on the things that were exciting about the game from day one. This has proved difficult: it's a competitive multiplayer strategy game, and we've spent a very long time working on gameplay before finalizing art. While this is ultimately good for the game, it's meant that we haven't had a large number of art assets to release to the press.

When things reached the point where the game was at a just-presentable stage, we wanted to find a way of giving people a taste of the gameplay before we were ready to release a trailer.

We knew from beta testing that the gameplay was addictive and interesting, even if the game wasn't able to sell itself just with a video at the current time. We came up the idea of actually letting people play the prototype in a public setting.

Live events are one area which a lot of developers shy away from: are these really worth doing, or are they just an unnecessary indulgence?

Industry marketing commentators like David Edery are fans, and major publishers go to great lengths to make an impact on such occasions: Activision's enormous DJ Hero launch party in Ibiza, for example. With an increasing number of game events and festivals springing up around the world, figuring out your strategy to take advantage of these could end up paying dividends.

As we'd never run an event before, it had to be a worthy experiment of a significant size that would give us good data about how to deal with such things in the future.

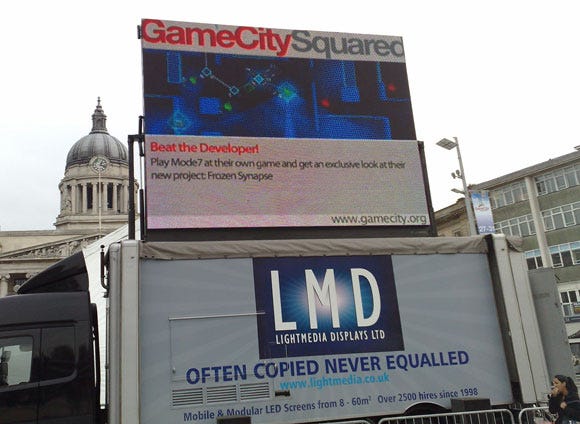

Nottingham's GameCity festival was our immediate choice of location: I'd contributed to every single one of these brilliant annual games culture events to date, and had an existing good relationship with the organizers. We knew that if we put effort into an event there, we'd get their full support.

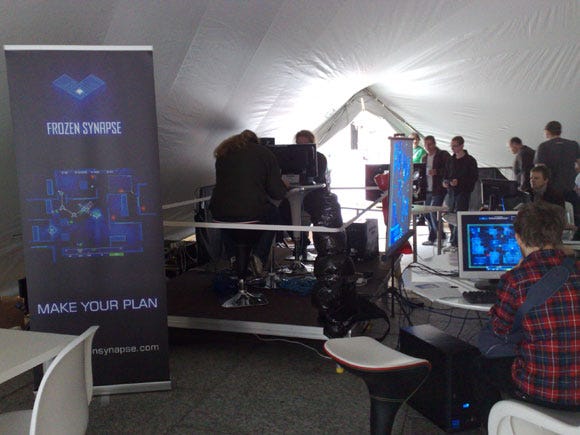

After contacting them, we were told that we could get allocated a space in a gigantic marquee which was going to fill the town square -- a great location to come face-to-face with the hairy masses! Here's a quick video of how things ended up, and here's a sillier video showcasing our festival experiences.

The inside of the tent at GameCity Squared

The correct approach, we thought, would be to try and get the game into the best possible state, then create a short, punchy game mode that could be played quickly in a festival setting.

I asked our lead designer Ian Hardingham how he came up with the mode which we eventually used - you can see our tutorial video for it here.

"A lot has been written recently about how games are too hard. But when you have to keep someone playing for a short amount of time, difficulty is actually one of the best tools at your disposal. I wanted to create an experience with a clear goal, but one that was actually very difficult at first to achieve. Rather than putting people off, this challenged them, and they suddenly became invested: they wanted to win.

"It was important that the goal be very simple. I started off with 'kill the enemy', but Frozen Synapse has some pretty complicated combat mechanics -- I didn't want people to think that they were failing because they just didn't know the game well enough.

"So I moved to an even simpler goal: 'get to these locations'. This has a really great benefit in that your first attempt is very obvious -- place a waypoint where you want to go and see what happens. The first thing that players do in your game must be very obvious. The rest will then emerge -- they will see how their first attempt failed and they'll start tweaking."

We started an art push to make sure that we had some coverage of everything (no missing animations, no horrible glitches etc.) and also began work on this new mode.

At the same time, we needed to decide on a concept for the event: Ian suggested running a competition. We wanted to keep some control over what happened, so the idea of "Beat the Game Designers" came up: members of the public would try and literally beat us at our own game.

With the concept locked, we needed a format: we would have a pair of computers networked together, where members of the public could take on one of the developers, and five or six others stations round them where people could try their hand against levels we'd set up.

I was initially against the idea of relying on networking even two machines together. In a live situation, any equipment will spontaneously invent a new and complex method of going wrong: this is an inevitability. I was eventually talked into letting this one slide, after being convinced that the two exact machines, the exact network hub and the exact cables being used would be tested throughly in advance. This turned out to be okay!

When conceptualizing an event, it really pays to think about the key facets of your game. For something like a puzzle game, you might set up a station with an "unbeatable puzzle" and try to get people to defeat it. Assuming you're going to have trial stations at your event, you're essentially creating a fairground attraction -- something that will make people want to come up and play immediately -- and your approach will be different dependent on your concept.

Think about what people can accomplish in your game in a five minute play session, and base your design around that. Not only will that benefit your event, it will also help when it comes to pitching your game.

As a final twist to our event, if anyone managed to get above a certain score, either against us or against an AI opponent, they would go into a draw to win... something.

That meant we needed prizes. I knew from my past experience working on magazines that companies are perfectly happy to dole out prizes if you...

Don't come across like a moron

Offer some tangible data about why it's a good idea that they give you a prize (marketing people like data)

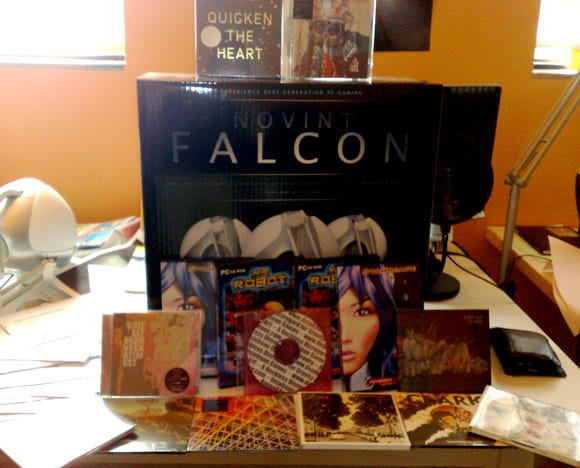

To that end, I asked GameCity for some stats about the number of visitors who would be attending, and set to work ringing round our friends in other companies. Novint Tehnologies donated our star prize, a Falcon controller: we were delighted to get this, as it's a big, visually obvious, slightly left-field prize that would intrigue people.

We also got a selection of CD's from Warp Records (lending us a bit of street cred with the kids, or something) and some brilliant indie games from Moonpod Games and Dejobaan Games.

I also contacted every PC manufacturer I could find to see if they were willing to donate machines for us to use at the event. I was pretty disappointed with this: despite the fact that it was a genuinely a pretty decent branding opportunity, I didn't manage to get even a single response.

I don't blame the manufacturers for this in any way -- getting contacts at big companies is solely a function of time and persistence. A lot of indies whine about people in big companies being hard to talk to: this is just a defense mechanism to protect these people from bullshit and, as a small unknown company, your job is to hack your way in through any legal means possible.

Most people in bigger companies would love to talk to you, if you're interesting. They might want to do business with you, pump you for information, or laugh at you behind your back; mostly all three, in my experience, but at least it's possible to get the ear of such people through hard work!

I failed at this in this instance and it's something to which I should have allocated more time: we were going to have to beg, borrow and steal computers.

With the format ready and approved by the organizers, we needed to start thinking about logistics. As I mentioned, I wanted to plan in great detail and make sure that we didn't have any disasters. Here's a list of things I needed to take into account -- a quick warning, if you're not currently thinking about planning an event, this will be deathly boring, so please look away now.

Personal

Transport (storage capacity)

Hotels and parking (proximity, storage facilities, safety, cost)

Venue

Accessibility (vehicle access, when we were allowed to get in and get out)

General security (would we need to physically secure computers etc.)

Stewards / event-specific security (would we have constant coverage by event stewards; would we need to lock-down Windows on each machine etc.)

Equipment / Furniture

Tables and chairs (size and stability!)

Power (would there be sufficient sockets in the correct part of the marquee; where could we lay cables safely)

Computers (would we have enough of sufficient spec?)

Prizes (transporting and securing these)

Projector and screen (would this be provided by the venue; format; size)

TV and DVD player (would these reliably play the DVD we'd burnt and loop it correctly; where could we set these up)

Cables for everything (...and some redunancy!)

Lots of pens and paper (strangely difficult to get hold of at short notice in some towns!)

Branding and directional signs (in case people needed to be directed to where we were; so people knew what the hell was going on)

I don't need to go into most of these further, but there are a few points I should mention.

It pays to discuss literally all of your plans, to the point of boredom, with the organizers. You need to know the details of all of the above as soon as possible, even if you're doing a small-scale event: you will always have to solve short-term problems when you get there, but don't ever leave a decision until then. We still had to run out and buy cables 30 minutes before the start (something to do with the projector, which we didn't have access to beforehand and were told would come with appropriate cables) despite all of my planning!

There might be some unexpected issues. For example, we planned to have flyers printed and distribute these on the days before the event. Shortly after we'd paid for them to be printed, we were told that we might need a license from the local council to distribute them, which would have been prohibitively expensive. This confusion was eventually straightened out by the GameCity organizers, who worked very hard to ensure that we could do everything we wanted, but it could have been a real problem.

Similarly, cars needed special passes to be allowed onto the market square -- due to our advance planning in securing these we were allowed to bring in our vehicles when one of the vans actually affiliated with the festival was turned away! It's always worth checking if there are any arcane local bylaws you might be in danger of violating...

We had decided that myself, our level designer Robin and his brother Tristan (who had very kindly volunteered to help out and donated his PC) would go down at the start of the festival and flyer, while Ian (who was away working) would join us the day before the event.

We spoke to a lot of people while flyering and gave out 2000 of the little buggers -- I was disappointed that this didn't particularly seem to affect either our web traffic or the number of people who eventually turned up to the event. I'm still pleased we did this, because now I know for a fact that flyering even inside a very open festival environment like that does little. I would still keep some printed material available for people to take away, but not push this actively next time.

This would have also meant that we could have dramatically reduced the cost by having the three of us there for less time.

Both Robin (who actually injured his foot while walking around at one point -- never underestimate the unexpected) and Tristan did an amazing job of helping out. On the plus side, people did notice what we were doing and it gave us more of a presence at the festival if nothing else.

Having this number of people was vital when it came to setting up and running the event, so if anything, I would recommend you have at least one person per three stations. These people can be festival stewards / volunteers (as long as you can quickly brief them beforehand) if such people are available.

It's important to take into account the cost of having people away from the office, especially in a small company: certain things will have to be delayed.

On the day itself, we managed to get in successfully, with only a little bit of cable juggling.

People responded very well to a tutorial video we'd made that was playing as they came in. Having a short video which explains gameplay is a really, really useful early marketing tool and can function pretty well in this context.

The festival game mode we created was a success: people got it, understood it quickly and found it fun and challenging. It's such a good game mode that we're actually using it as one of the main components of multiplayer. The benefits of trying to sell your game quickly in a pressurized environment really rub off and have a net positive impact on design.

We did learn quite a lot about the game from observing people playing -- there are still some difficulties with the interface that we're getting over. We found that people were either hooked immediately or very turned off by the game; it's pretty divisive. We'd anticipated this, but it really brought home to me how much we'll need to target our advertising when we get towards launch: we could easily waste money on useless ad impressions unless we hit our target square on.

A lot of people liked it; people walking in literally off the street, sitting down and playing our game like it was an arcade machine was an amazing experience and very motivating. Some people got addicted and stayed for hours, chatting with us and even teaching new people how to play.

I think this whole atmosphere was a particular boost for Ian, who often has to put up with my endless whinging about accessibility and instant impact: he's managed to create a game which a lot of people are going to love and we know this now for a fact!

I was glad to see that great security was provided by GameCity. We only had one minor "quit-to-desktop" incident (none of the "sneakily opening Steam and running Half-Life 2" which was happening over at the IndieCade event though!). I was really surprised that no members of the public messed around or tried to destroy anything -- I think that was a tribute to the friendly, calm atmosphere which GameCity had managed to create, more than anything else.

In terms of our setup, it worked well. We didn't need to pay for a huge amount of branding stuff: a single good-looking professional banner was fine. We had a lot of flyers everywhere, so people did know the name of the game and would have seen some branded stuff if they came anywhere near our tables.

The best thing about the banner is that it can come with us to every single event we do, spreading out the cost: always look for things that can be re-used if possible.

Getting out went fine, until a beyond-my-control hiccup with transport meant that we had to lug all of our equipment into a taxi using a long caterpillar-like line of stewards!

This was fine, but it really brought home to me how much you have to take care of event aspects that are within your sphere of control: be a total perfectionist even if it starts (but only starts, mind) to wind up other people!

Overall, the event was a success. Having a presence at the festival, meeting press and other devs, doing interviews, getting design feedback, motivating the team and gaining some new committed fans was fantastic. Our activities there generated some interesting data and directly led to a few further opportunities, including appearances at other events, that I'm still following up.

I felt that numerically, if we'd spend the same amount on CPC advertising we would have had a better return in terms of sign-ups -- we only generated 40 mailing list sign-ups in the eight hours. This was a disappointment: I think I would have put better sign-up mechanisms in place (people had to write their address on a piece of paper) had I anticipated this problem. It's definitely something to watch out for.

I did wish that we could have been selling something at the event to recoup some costs: developers like The Behemoth use these opportunities to market their brilliant merchandise, for example. A lot of people were pumped about the game and would have wanted to take things away with them.

In terms of scale, I think we were slightly over-the-top. This was the way I'd planned it, but I think a lot of the benefits we experienced could have been derived from a smaller presence with fewer people and machines.

Having said that, if more stewards and machines were available, the event could have been run with just one of us there. This is something I'm currently talking to the organisers about providing. It's understandably quite a difficult issue. If you are running a festival, then having demo stations available for indies to install their games on would be an amazing carrot to bring some really talented people your way and add a lot of color to what you're doing.

In future, I'd like to do more regular events tied in with our other marketing: it's a good way of getting into people's faces and pushing your game. Working out a schedule for these is difficult when you have limited resources, so we're planning on targeting bigger ones and then squeezing in others when we have time.

You really need every advantage you can get, and if people get excited about your game at a show then that can only be a good thing. Be careful though, it's easy waste money and, like all marketing, you need to think about each activity in the context of the whole effort, rather than as being the one golden ticket to promoting your product.

I believed we proved that tiny companies can run successful events, provided they're planned correctly. I would urge other indies to get out there and do something adventurous: it's becoming increasingly difficult to get noticed and so going out on a limb is often best.

Support large-scale events like GameCity which are worth believing in and make the games industry a good place to be: use your influence as creators to help all of us get more opportunities to connect with the public.

Strong companies that think in the long-term prize every point of contact with a customer or potential customer: it's an opportunity to show people that your products are worthwhile because you care about their needs and desires.

This doesn't mean that you have to spend huge amounts of money: it just means that you have to treat people nicely and create an interesting environment for them. Meeting your fans and people interested in your game face-to-face is invaluable. I thoroughly recommend it.

Thanks to Bin, Ian, Tristan, our sponsors and the entire GameCity team and everyone who came to our event for making it a success!

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like