Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

What does litigation mean in the games industry? How far back does it go? And is it necessary? Dr. S. Gregory Boyd returns to Gamasutra with a detailed feature on the history of litigation, as it pertains to games, with examples ranging from Pong to Duke Nukem 3D.

December 18, 2006

Author: by S. Gregory Boyd

At conferences you will hear people wonder aloud about what it was like to work in the game industry before “lawyers ruined it with litigation.” Curse the dirty lawyers! Those were the good old days and we wish we could return to them.

When were these days that game developers lived in happy little communes and even the word lawsuit was unknown to them? The answer is never and in some cases we should be glad of that. A portion of the litigation in every industry, even the game industry, actually leads to positive results for the industry as a whole. As an example, consider all of the First Amendment protection that has come from the ESA cases overturning unconstitutional censorship and distribution laws.

The game industry has had litigation as long as there has been a game industry. In fact, there were patent cases involving Pong even as early as 1977 and there may be cases even earlier than that.1 Controversies and the litigations that accompany them have continued to the present day and will continue as long as there is a game industry.

Another basic misunderstanding is that lawyers are the cause of litigation. In fact, people disagreeing over something and caring enough to “fight” about it is the root cause of litigation. Under the vast majority of circumstances, an attorney cannot sue anyone unless he represents a client that wants the case brought. Litigation is just the mechanism that “civilized” countries use to work through controversy, and it is superior to many of the previous methods such as gladiatorial combat.

Yet, I too long for the days of simple gladiatorial combat to settle differences, and I would gladly be put out of work as an attorney if that ever comes back into fashion. Imagine Douglas Lowenstein versus Jack Thompson in a battle to death over First Amendment protection for games. Aside from this brief bit of philosophizing and dreaming, litigation is an enduring fact in the game industry and it is often the cause of robust change. As professionals working in games, we should understand the importance of litigation and how it has shaped the craft of making games.

The purpose of this article is to highlight a few of the interesting game cases (or types of cases) and consider how these have affected the industry. Readers may be surprised, but some of these cases produced real changes for the better.

This article should not be considered a list of the “biggest” or the “most important” cases in the game industry. Instead, think of this article as just an introduction to some of the more interesting battles over the last 30 years.

Copyright is probably the most important protection for computer and video games. This allows game companies to enter into complex game development and distribution contracts. Copyright allows companies to take action against hackers and pirates, even invoking criminal charges with the FBI. We take it for granted that games enjoy this broad protection, but this was not always the case.

One of the first cases to set copyright firmly on the road to covering games is not merely an important case in the history of the game industry, it is also an important case in the history of intellectual property law.2 To add to the historical importance, the opinion was written by future Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsberg when she was a judge for the Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia.

The game Breakout, now almost 30 years old, was a test case for copyright protection in games. Writing that sentence makes me feel so old that I need to find my false teeth and some Depends Undergarments just to brace myself for writing the next sentence because for many of you, Breakout was “before your time.”

Breakout was a 2D game for the Atari 2600 that involved moving a simple bar or “paddle” across the bottom of the screen to hit a ball that bounced up into a four-color brick wall. The game had four different tones to make up the soundtrack. When the ball bounced up into the bricks, it ricocheted back down and had to be hit again with the paddle. When the player failed to bounce the ball back up, the player lost a ball. This process continued until the player ran out of balls.

Today, registering a game with the Copyright Office is a very simple process. It literally involves filling out a short form and mailing in a fee less than $50. Atari attempted to register the copyright for Breakout with the United States Copyright Office and was denied. This began a struggle involving Atari, the Copyright Office, and U.S. courts that lasted more than 5 years. The Copyright Office resisted this registration because it stated that Breakout did not demonstrate the required artistic originality for registration.

In the end, the Copyright Office registered the game and with the support of previous court decisions, this helped pave the way for copyright protection for all modern games.

Magnavox Company v. Chicago Dynamic Industries, 201 U.S.P.Q. 25 (N.D. Ill. 1977).

Atari Games Corp. v. Oman, 979 F.2d 242 (D.C. Cir. 1992). This was not the first case to discuss games and copyright, but because of the judge that wrote the opinion, its position as an appeals court case, and the long struggle to register Breakout, it is considered one of the most important game copyright cases of the period. Other copyright cases pre-dating this one included cases concerning the games Pac-Man, Galaxian, Donkey Kong and Scramble.

Imagine the next game your company makes includes a tool set and the ability for players to make mods and create their own levels. Of course, this is very common in modern PC games. Now imagine that someone could collect those mods and user created levels and sell them. By selling them, I mean with retail distribution in major stores without your permission and without royalties. This whole ideas strikes us as crazy in 2006, but there was a time when these rights were questioned.

The case involving this issue surrounded the game Duke Nukem 3D.3 Duke Nukem 3D was a first person shooter created by 3D Realms for the PC and released in 1996. The play style was similar to many other games of the period including Doom and Hexen. It was probably most memorable for Duke’s simultaneously pithy, charming, and offensive dialogue. The game was also one of the first to include a “Build Editor” that allowed users to create and trade their own user created levels. The game license included the statement that any user made levels could be given away, but not sold.

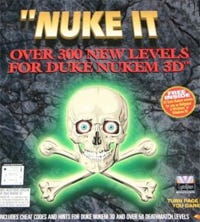

A company named Micro Star created a compilation of 300 user levels on a CD and attempted to sell these through retail distribution under the title “Nuke It.” In summary, Micro Star argued three positions. First, this was not a violation of copyright because the user maps did not contain any art assets. The files on the CD merely called for the placement of art and sound assets. Secondly, even if it was a copyright violation, it was “fair use.” Third, even if the first two arguments were not true, the game license was invalid and 3D Realms had given up copyright rights when it allowed users to make their own levels.

The lower court in California ruled in favor of Micro Star on some of the copyright issues and that brought the case to the court of appeals. The 9th Circuit court of appeals overturned this decision and held that Micro Star’s actions were copyright infringement and would not allow the sale.

The lower court in California ruled in favor of Micro Star on some of the copyright issues and that brought the case to the court of appeals. The 9th Circuit court of appeals overturned this decision and held that Micro Star’s actions were copyright infringement and would not allow the sale.

If this case had gone differently, the game industry might be a very different place. Imagine store shelves and digital distribution filled with collections of user created content where the original publisher/developer has no creative control over the product or royalties on the sales.

Similar to the previous battle for copyright protection, the game industry is now fighting for the additional respect that comes from First Amendment protection of artistic expression. To date, nine state laws attempting to limit the sale of games have been overturned as unconstitutional attacks on games as speech under the First Amendment.

A variety of laws have been put forth by state legislature to act toward censoring game content or controlling the sale of games. As a rule, be immediately suspicious of any legislation proposed in the name of “security” or “protecting our children.” The result is often a jumbo size bite taken out of artistic expression and individual liberty.

To date, the ESA has fought and won nine out of nine cases on these issues, having the state laws declared unconstitutional. Furthermore, the ESA has sought and won more than $1.5 million dollars in attorneys fees. In a December 2, 2006 press release, the President of the ESA, Douglas Lowenstein was quoted as saying:

States that pass laws regulating video game sales might as well just tell voters they have a new way to throw away their tax dollars on wasteful and pointless political exercises that do nothing to improve the quality of life in the state. In nine out of nine cases in the past six years, judges have struck down these clearly unconstitutional laws, and in each instance ESA has or will recover its legal fees from the states. What's worse, the politicians proposing and voting for these laws know this will be the outcome. Our hope is that we can stop this pick pocketing of taxpayers and start working cooperatively, as we have with several states and elected officials, to implement truly effective programs to educate parents to use the tools industry has made available -- from ESRB ratings to parental control technologies.

This is certainly an instance where litigation has done a great deal of good for the industry. These cases have helped raise the profile of the industry in the news and encouraged an increased respect for the craft of making games.

3. Micro Star v. Formgen, 154 F.3d 1107 (9th Cir.).

The final group of cases to discuss are the newest type in this article. These cases have developed over the past few years and that will probably continue in coming years. These cases may be referred to collectively as “patent troll” cases.

The term patent troll is a very dirty word in IP law, and no one wants the name applied to them. Definitions of the term vary, mostly because companies want to find a way to define it so their own company falls outside the definition. For the purposes of this article, a patent troll is a company that has four characteristics:

it holds patents

it does not invent anything itself

it does not manufacture its own products

it threatens to sue people with those patents

Another less derogatory name for this type of entity is “patent licensing company.” Some people would say these companies do not really contribute anything of substance (beyond the promise not to sue) to the creative endeavor. Many people in the game industry consider them sand in the wheels of progress.

Under any definition, the general idea behind a patent troll is easy to understand. A person raises money to fund a company, uses that money to buy patents (often from failed businesses), then threatens successful companies with litigation unless they pay for a license to the patents. If those companies do not pay, they get sued for patent infringement, a cost that can easily reach into the millions of dollars before judicial decision.

Views on this type of practice vary. Some describe it as a game of chicken combined with elements of highway robbery. Others see it as protecting the ideas of small inventors from being stolen and used by large companies without paying the proper fee. Under any description, this type of litigation was unheard of at the start of the game industry, but is becoming increasingly common.

The goal of this type of litigation is to sue a large number of game companies with a group of patents that arguably cover a very basic technology (such as panning and zooming in three dimensions). This leads to the greatest potential exposure for game companies and yields the greatest potential profit for the trolls.

The patent troll also takes advantage of plaintiff economies of scale in the litigation process. By that, I mean that the cost to sue 20 companies is not 20 times greater than the cost to sue one company. Yet, defending a case can be almost as expensive (sometimes more expensive) if there is a large group of co-defendants. This gives a patent troll the incentive to bring the case against as many deep-pocketed companies as it can plausibly bring the case against. Since the patent troll has no products, no inventions, and no purpose beyond these litigations, a good portion of the litigation process is fairly easy for the company.

The patent troll does have to work on showing the patents are valid and infringed, but giving up all company records can be as simple as giving up the patents, patent purchase agreements, and the letters the company has written to the accused infringers. The patent troll can literally turn over every company record in just a few boxes and wash its hands of the most burdensome part of the discovery process.

On the other hand, the defendants are also responsible for turning over the relevant information for all of their accused games/products (often including game code, marketing material, and sales figures). Keep in mind also that patents are presumed valid in litigation and the defendants have to show by “clear and convincing” evidence that the patents are invalid – a lot of hard work. Imagine the burden that all of this puts on a company like Microsoft, Nintendo, or a large developer. Furthermore, imagine how asymmetric the burden (and cost) is when compared to the patent troll.

All of this motivates defendant companies to settle the litigation and license the patents as quickly as possible. Even if a game company is reasonably certain that its products do not infringe certain patents or that the patents are invalid, trial is an expensive, complicated, and unpredictable process. These patent troll licensing cases are certain to increase the importance of patents in the game industry and change the way we do business in the coming decades.

Litigations have always been part of the game industry, just as they are part of every successful commercial endeavor. Yet, fighting through these controversies using the litigation process has helped bring about important decisions that shape the work we do every day.

I am not proposing we embrace litigation as positive, but I do mean that it is a fact of any successful industry that needs to be respected and understood as we move forward. In some instances, such as in copyright registration and First Amendment protection, the results can be a great boon for the industry as a whole. Furthermore, increasing litigation is an indicator that the industry is growing in financial and cultural importance. Acknowledging this historical importance and industry shaping power of litigation is critical to any thorough understanding of the game business.

DISCLAIMER: This article is written for educational purposes. Nothing herein should be considered as legal advice or as forming an attorney client relationship. The author’s views are his own and do not represent those of CMP, Gamasutra, Kenyon & Kenyon or his clients. Every situation is different and the author strongly urges you to seek competent specialized advice for legal issues.

Business and Legal Primer for Game Development edited by S. Gregory Boyd and Brian Green, Charles River Media, 2007

Video Game Law by Jon Festinger, Lexis Nexis Canda, 2005

Nadia Oxford’s article on game cases from 2005

Davis and Company Video Game Law Blog

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like