Koji Igarashi on the power and responsibility of being Kickstarter-funded

Gamasutra had a chance to sit down with Koji Igarashi and talk about the successful Kickstarter campaign for Bloodstained: Ritual of the Night, and how he feels about breaking records, and breaking free.

Right now, Koji Igarashi has the most successful Kickstarter campaign for a video game yet seen. His dream of Bloodstained: Ritual of the Night -- a spiritual successor to the 2D Castlevania games he helmed over the course of the 2000s, and of course, the ultimate classic, Symphony of the Night -- has captured the hearts and minds of a huge swath of fans.

Gamasutra had a chance to sit down with Igarashi at E3 in Los Angeles last week and speak to him about his thoughts coming out of the campaign, and his goals for the game. He also spoke about his thoughts on working with publishers, and shared some of his game design ideas, too.

During the interview, his agent, former Capcom Japan producer Ben Judd, joined in. Judd both interpreted the questions and answers, and also shared his own comments -- adding clarity and context, most frequently about the Kickstarter campaign, which he was a big part of.

Koji "IGA" Igarashi

On the Kickstarter campaign, stretch goals, and scope

Scope creep is really difficult to deal with as a developer. You must have gone into this with some anticipation of hitting stretch goals -- but you hit a lot. How do you deal with that?

Koji Igarashi: So it's kind of a fine art in where you set a stretch goal. And there are lots of different theories on Kickstarter -- whether you should set it for the actual cost, whether you should set it for half of the cost, whether you should set it just to try and increase excitement and hope you over-deliver. There are lots of different ways of thinking about them.

The general rule is that the money that you raise on Kickstarter is half of what you're going to get. So we set a lot of stretch goals that were about $250,000 apart, which means that the actual development budget that we would get to spend would be $125,000 -- so not a lot.

So what you're trying to do is measure the momentum of how quickly the money is coming in, with what you feel is a realistic goal that comes in around that range. Now, it's not an exact science, so there are going to be some stretch goals, true enough, aren't going to cost $125,000.

Ben Judd: And what you end up doing is you build yourself a small buffer. And the idea is -- and you at Gamasutra might know this, but the average, everyday Joe Gamer might not -- is that most games are developed with about a 10 to 20 percent buffer, when the development budget comes in from the publisher, to handle when things are delayed, or when you need to throw more people on it, or whatever. It's your safety net, so to speak.

So this [project] is still baking in a safety net on the front-end. However, as you get higher up the ladder, and you need to come up with things that are more interesting, or more powerful, to push the game development engine forward, a lot of times you end up going over, and sucking away your buffer.

So he used the very specific example of the $4.5, $4.75 [million] mini-game that we're creating. That's more than the amount of money that we're going to get for that stretch goal, where we set it at. So we basically ate through any buffer that we had to be able to offer that as an option.

But where we ended with the Kickstarter campaign was feeling that, yes, there are a lot of things to make, but feeling confident that, yes, the money will be enough to cover those things while still making a great game with a lot of modes, and still get very close to when we plan to release it.

This is the first game in a new franchise. The scope of the game is going to be very large. I don't know how you might fund future installments, but we all know that as series go on, sometimes you get more or less money, right? Are you creating a situation where the first game is too big, in a way?

BJ: To be 100 percent honest, you're right -- there's a lot of stuff that we're going to shove into this first game, and that means, so where do you go from here? Where's your bigger, badder, better for the second game or the third game?

KI: I feel that modes, that's not what sells the game. It's usually the core gameplay. And of course you can change the key system.

BJ: As a matter of fact, that's what he's famous for doing, is taking some of the key pillars of what makes the Castlevania games great and change the core system to provide a very similar feel on the outside, but still a very different game on the inside. And that's going to be the thing that will make it feel fresh from game to game.

KI: Also, it's a very organic development. Insomuch as, as we build out this first game. Maybe one or two of the modes, not a lot of people play. And we'll take that feedback and that'll be a mode that you wouldn't necessarily put in the second one, and maybe put more emphasis on the modes people like.

And again, as a starting point, putting all this emphasis on content, while it is a bit risky, it will help us hopefully shape an even better second game, which is obviously the end goal for most productions.

We've talked a lot over the years, and of course I watched all of the videos on your Kickstarter. I get the sense that you are a very careful developer. But there is one element of the Kickstarter that is out of your control: How much money you got in the end. How does it feel to have an aspect of uncertainty, even if it's a good uncertainty?

BJ: You're right. He is a very safe person, as far as a planner goes. He's been able to create the same game multiple times, and he's been able to do that under a very tight schedule without being delayed, because of his personality type.

KI: So the one thing that we did, of course, that made it something that we could promise, and commit to, and make it safer... For the campaign, as we've said, a budget was guaranteed by back-end investment. So we knew that when we got the additional amount, that [investment] would complete the core game. And so that was the core game that we had in mind; we could make it, for sure, with that budget. We had already planned it out, what the assets were going to cost, etcetera.

What that means is that you are in a very pure place for planning out stretch goals. Because you look at each stretch goal and you ask, "How much is this going to cost?" And as we mentioned before, there were some that included a front-end buffer. Again, every developer needs a buffer to be safe, to have a safety net. As we planned it, the earlier stretch goals had a bit more of a buffer. And every once in a while there would come a stretch goal that would use up some of that buffer. And the needle came closer and closer to the reality.

But then as we got closer and closer to the end of the campaign, and we knew there were only a few days, and only so much money that would come in, the different stretch goals we were promising would eat up more and more of the buffer. So the idea was that we would end at the finish line promising a game that we could deliver without any leftover buffer, so that it wasn't like, "Hey, we just have extra money that we weren't going use," because that would piss off a fan, or a backer, if they felt that that was happening.

BJ: So it was having a very daily planned-out organic flow of these stretch goals. Of course, from the campaign side, I was a part of that -- almost from a two or three [times] daily basis, we were looking at the user comments, we were taking that feedback, we were talking with the production side.

Inti [Creates] would come in and say, "Look, we can't do that mode for that much money. It's going to have to be placed way back here, and we'll have to gain this much buffer to commit to it." There were multiple discussions about a create-your-own mode, or 16 or 32-bit, or anything like that. But the budget would not fit. All of that was done through very long planning that was done on a very flexible basis.

Obviously you must have felt very glad about getting the extra money. But I'm surprised to hear how responsible you felt to spend it. Because there are two ways you can look at Kickstarter backers: As preorders, or as the people who are driving the production of the game. And those are fundamentally different, I think.

KI: We ended up using it all. It's all gone. There's a little risk that comes with guaranteeing you're going to put in modes and things into the game that guarantee that you're not going to have as much of a safety net -- but it never, ever even occurred to me to think of this as profit we would save again for a rainy day, as if this was a preorder or something like this. From my perspective, these are people that are helping me create the best game I could, and I am promising to make the best game I could with it -- not make most of the best game I could, and save some money off for a rainy day.

BJ: I'm going to give you one aside to this, which is not coming from him; it's coming from me. A lot of people don't realize that we did offer both digital and packaged versions across the board for a wide variety of consoles. That 30 percent first-party royalty has to get paid, for everything -- whether it's Microsoft, Sony, or Nintendo. So you have to figure that every $60 packaged version, or every $28 digital version -- guess what 30 percent of that is doing? It's going into first-party's pockets, just like every other game.

For us to save that money to pay them isn't necessarily a bad thing business-wise, but, again, that's going to have to be paid at some point or another. That's why you'll see a lot of Kickstarter campaigns focus only on PC. It's not something that gets paid on PC. Or only offer packaged versions for PC -- because they don't want to pay that 30 percent royalty.

Does this mark a fundamental change in your career, and how you're going to make games in the future?

KI: This is something that all companies learn when they go independent as a developer: You now have this new piece of, "Where am I going to get the money to make the game?" As far as my career, it changed drastically the second I left Konami. Up till then, I'd always worked at a publisher and the money came to me, and I was told I have this much budget, and make the game.

Now I have this back-end piece of, "Okay, I've quit the company. There's not just a treasure chest with money lying in front of me. I'm going to have to find a way to earn it to make the game." So Kickstarter, for this time, was the right method to earn the money, in addition with the background funding, to make the game that I needed to make. But from here on out as an independent developer, that will always be something I need to think about to make games.

On publishers vs. crowdfunding

Of course, because of this, I looked back at the lot of the conversations we've had over the years. There was a lot of talk about constraints; Konami put you under a lot of constraints on your prior projects -- "change the art style," or the budget, or, "this isn't selling in Japan!" But this is the opposite. So in that way, this is a new challenge. So how do you mentally approach that challenge?

BJ: The easiest way to be creative is when you have limitations, yes.

KI: First, I don't want people to get the wrong idea. It's very easy to vilify Konami and make it seem like they're this very evil corporation. But as far as myself, and my career as a producer at Konami, I had a lot of freedom there. And while there were, of course, budgetary limitations that were put on me, I still feel like I had a decent enough budget to make a good game. It wasn't like I was getting half of what I needed, or anything like that.

As far as those discussions we may have had in the past about restrictions, well, there are always restrictions on any creator. I don't feel that they're necessarily 100 percent unfair.

However, that being said, as far as being out of that umbrella and having my own independent company, and being able to make the game how I want it, with very little restrictions, unfortunately, that's not the case. Restrictions come, usually from where funding or money comes from. In the case of the publisher, obviously, everyone has bosses at the publisher and that's going to determine how much money you have to spend and therefore which restrictions are at play.

As for a Kickstarter, your bosses are the backers. You have a lot more now. And so there are still restrictions that are put on you. I can't, all of a sudden, tell these 60,000 people, "Oh, well, you know what? I've decided I'm going to make a shooting game instead, because that's going to be awesome." They would say, "What? Hell no." So now, in fact, as a creator, you always have to paint within the lines, and there always are restrictions.

Speaking of bosses and publishers, there's a rumor about bosses and publishers. We saw Deep Silver register a trademark. Have you said anything about what's going on with that?

KI: As far as who is the publisher, or the back-end investor, that has not 100 percent officially come out. Honestly, it is 100 percent up to that person, or that organization. They're probably going to put together a press release or something to make that announcement official. When they choose to do that, that's kind of on their own timing.

I will say this. As far as one of the things that people are most worried about when the idea that a publisher comes into play is whether or not that creator is going to own the IP or not. I have answered before that this IP is mine, and that doesn't change. So everybody who has backed this project should be happy that they have given the creator a chance to own the IP, which is not easy to do these days in the industry. That should hopefully make them feel very happy, that they have empowered the creator that they like.

As far as Deep Silver registering the trademark, if we were to say that Deep Silver is the publisher, again, that's for them to announce. But if I were to say that, "Yes, that was the publisher," they probably registered the trademark to try and make sure that it was covered from other people registering the trademark, and they did it out of goodwill to make sure that it wouldn't go away.

BJ: At the end of the day, it's his IP. So if they were to become the ultimate, end-publisher of the game, it would be a situation which that trademark would revert to him.

Right now, Shenmue is on Kickstarter; you were on Kickstarter; Mighty No. 9 was on Kickstarter. And if you look at Western games, there are many popular rebirths of '90s PC IP. There's clearly a thirst for the games people grew up with, but publishers clearly do not want to address it. Can you talk about the mismatch there?

BJ: Games that you and I probably played when we were younger, it was a much smaller thing, a much smaller world.

KI: Ever since then, it's become a massive market, mass-consumer, and games have just grown to be this massive thing. It's put publishers into the position where their internal teams have gotten bigger and bigger, and the spends have gotten higher and higher.

So they've naturally gravitated toward the Hollywood model, as far as "shoot for the blockbuster." So they're looking for triple-A, 50-million, 100-million dollar productions. What that means a lot of the time is that something in the middle, or on the smaller side, isn't as appealing to them. That's one of the disconnects that I think is occurring.

BJ: While yes, it's true, some publishers are going into the indie space, a lot of times their forays involve something that is sub-million. So his game, or a game like Mighty No. 9, or certainly like a Shenmue, finds itself in an awkward middle ground, where the publishers just aren't excited for it, because it doesn't cover their internal high expense of cost for marketing and internal sales teams and etcetera. It's also not so cheap that if it does really blow up, it's going to make 'em a decent amount of money.

KI: I also feel that when you talk about Mega Man, or a Shenmue, or a Castlevania game, these are games that have been around for a long time, and they've had multiple installments, and the people who feel nostalgic for them are going to be 30-somethings or 40-somethings, people that have been playing games for a long time. Those people want what they want, and they're very passionate for those games, up to the point where they would spend $100, $200, $300 on a collectors' edition, or something like that, which totally fits within the Kickstarter scheme of things -- "less people, more money" helps cover that budget.

BJ: Whereas a publisher has to look back to mass-consumer, mass-market. They can't go to the retail chain and put out a $300 version of the game and expect it to sell to their traditional 500,000-unit, 1 million-unit, 5 million-unit sort of goalpost that they're after.

So unfortunately they're in two different directions: One is a specialty core group of consumers who have money to spend to show their excitement in the project; the other is mass-market, going for two million in sales, five million in sales -- but you're going for a fixed, lower price-point. Again, those are just disconnects that are naturally happening between what a big publisher does and what a mid-sized development needs.

KI: By that rationale I'm very happy that Kickstarter exists, because it fills a role that a traditional publisher can't.

The Symphony of the Night legacy

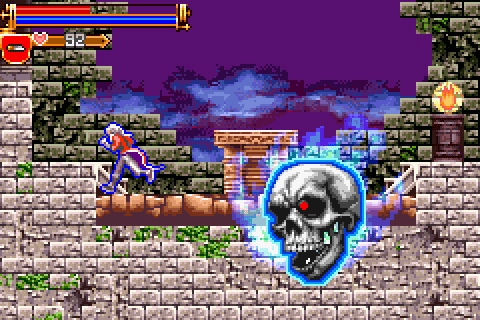

Castlevania: Harmony of Dissonance. Game Boy Advance, 2002.

This was Igarashi's first Castlevania title after Symphony of the Night, released five years later.

In all the GBA and DS Castlevania games, like you said, the feel was similar. But if you play them they can be quite different in terms of gameplay systems and also level structure.

I feel like a huge number of your backers were probably more Symphony of the Night fans. So how do you balance your natural tendency toward experimentation in the genre with satisfying people who were not necessarily along for the whole ride?

KI: I feel that while the core system itself may be different, and you can have a different core system -- the actual gameplay, the basics of what you're doing as far as killing a wide variety of different enemies and them dropping something that is later used to give you abilities, or actions, or magics -- those key pillars don't change from game to game. It's how you get that ability, whether it's mixed, whether it's pulled in directly, whether it's found. A lot of that, coupled with the idea that it's exploration, a gothic art style, these pillars I feel don't change in a major way.

BJ: Maybe for people expecting a Symphony of the Night 2, this game will not be that; but the core foundation of what makes his games his games is definitely going to be there, and it's going to be what sort of icing that we put on the cake that's going to be different -- that makes for a new sort of feel to the gameplay.

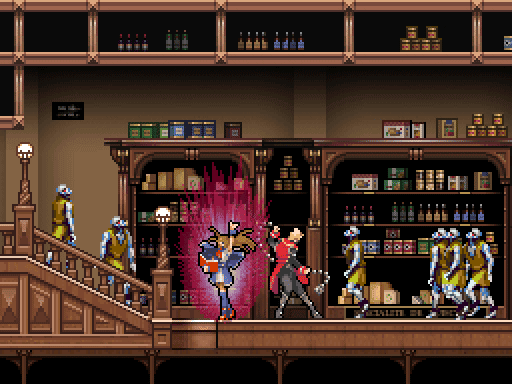

Castlevania: Symphony of the Night

You talked about older fans. I'm pushing 40, dear God, and of course I was there for Symphony of the Night in 1997. But something I thought about is that Symphony of the Night is on Xbox Live, it's on PSN. I feel like there are younger people playing it who weren't around for it; do you think that was important to attracting new players over the years?

KI: Yes, I think so.

BJ: Having the game available for a younger group to hear about potentially through word of mouth, or websites, or whatever, and discover it for themselves and enjoy it, it's definitely helped the longevity and the expansion of that franchise.

Discussing gameplay, and Igarashi's approach to it

Castlevania: Portrait of Ruin. Nintendo DS, 2006

One thing I think that the industry has struggled with overall is creating 2D games that feel great in 3D engines. What are your thoughts?

KI: I feel that with 2.5D, which is what I think you're talking about, the biggest challenge is where the character's feet are, and where the camera angle is -- how much you show of that. The reason why I say that is, the main character's feet, and where they are and where they are animated, becomes a big deal if you've got a platformer and you have to do severe jumps over tight distances.

A lot of 2.5D games revolve around that sort of gameplay, where you have to make those kinds of jumps. 3D models, in that type of gameplay, oftentimes become a challenge, when you're using a 3D engine.

Fortunately, a lot of that depends on the genre. The Symphony of the Night series and all of the games I've worked on, as I've hated strict jumps and death jumps, there's not a lot of that, so you can be more friendly with jump distances and what it takes to land on the next platform.

Symphony of the Night and all of the GBA and DS games revolved around having an interesting fighting system. Killing enemies -- that's been a lot of the fun. Not severe jumps and missing. Just by the nature of this game not needing that, I feel it is going to be more prone to feeling and fitting well as a 2.5D game compared to other games that have done it.

I watched the Ask IGAs that were posted as Kickstarter updates, and I found one interesting -- where someone asked about a combo-based combat system, and you said you were against putting in a combo system. But to ask about the question behind the question, how do you decide between the gameplay systems you want to stick to your guns, and when you want to change with the times?

BJ: He explains all of this, but then finishes with, "I don't really like 'hard' enemies." And again it goes back down to IGA's principles -- "I don't like really difficult jumps that kill you. I just don't like really 'hard' enemies."

[Ed. note: The word Igarashi uses is "katai," which means hard as in "not soft," not hard as in "challenging."]

KI: It doesn't fit this sort of gameplay, which is a much quicker-paced game. This game is more akin to: The enemy has a pattern, you dodge that pattern, it's got an opening, and even one or two hits can kill enemies in Castlevania games.

And that's to keep the tempo up, make it quick. If you have an enemy you need to do combos on, that instantly suggests the enemy is a "hard" enemy, insomuch as it's blocking high or low, or something like that, and it's totally going to slow down the gameplay for when you're fighting that enemy. And it's going to alter the whole key rhythm of what makes those games great. So while it might be a modern style that a lot of people are using in their games, it probably doesn't fit into this sort of a game.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like

.jpeg?width=700&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)