Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

What contributed to the closure of Homefront developer Kaos Studios, once the shining hope for the resurrection of embattled publisher THQ? In this investigative piece, Leigh Alexander speaks to former staffers to get the inside story.

One of the biggest legacies this console generation will leave has been the business shift for core games on retail shelves. Over the past several years, triple-A has become a space where only the absolute top-tier titles sell, especially in the first-person shooter genre. Even decent sales and decent quality aren't enough, and with today's budgets, "close, but no cigar" can even be lethal to a studio.

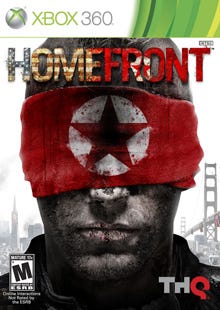

THQ's Homefront sold a million copies in its first week and scored a 70 on Metacritic, neither an excellent nor devastating score. Given the genre's popularity, though, Homefront could have been the start of great things for the development team, Kaos Studios. Audiences seemed to find the game's premise, which casts players as resistance members in an imagined future a North Korean invasion of America, refreshing, and reviewers consistently appreciated its team-based multiplayer in particular.

The ability to innovate and create online modes that felt fresh should have spelled the potential for Kaos to be an asset to THQ, which was at the time aiming to go head-to-head with the likes of EA and Activision in the popular genre. But instead, the publisher closed the studio just over a year ago, shunting the development of Homefront 2 to Crytek.

THQ's investors were impatient, and the publisher was already ankle-deep in the strategy and finance problems that have continued to dog it since Homefront's 2011 launch, and it simply could no longer afford anything less than spectacular rescue. It could no longer afford Kaos.

Danny Bilson, the EVP of core games who was Homefront's most visible executive advocate, ultimately stepped down this past May, with Naughty Dog co-founder Jason Rubin swooping in to try and sort things out for the studios, in the role of president. The publisher has significant challenges ahead.

But Kaos was much more than an expensive failure. The real reason Kaos Studios failed wasn't just-average performance for Homefront, nor was it the high cost of business in New York City. Gamasutra talked to scores of former employees about the death of their studio -- assembling what's ultimately a fascinating cautionary tale about how lethal mismanagement and culture problems can be.

Inside the Kaos collapse is a story of a studio that ramped up too quickly under too much pressure, strove beyond its means, and struggled with uncertainty about its future, as well as creative and interpersonal conflicts.

And although speculation in the press and implications from THQ itself suggested that the high cost of business in New York City played a major role in the closure, employees say the studio was no more expensive than comparable ones in San Francisco or Los Angeles. Some former Kaos staffers tell us they knew the studio wouldn't survive even before Homefront shipped.

Kaos Studios began when four friends -- Frank Delise, Brian Holinka, Stephen Wells, and Tim Brophy -- developed an incredibly successful and acclaimed Battlefield 1942 mod called Desert Combat. The mod's success led to the team forming Trauma Studios, which Digital Illusions CE quickly bought up in 2004 to help develop Battlefield 2.

Kaos Studios began when four friends -- Frank Delise, Brian Holinka, Stephen Wells, and Tim Brophy -- developed an incredibly successful and acclaimed Battlefield 1942 mod called Desert Combat. The mod's success led to the team forming Trauma Studios, which Digital Illusions CE quickly bought up in 2004 to help develop Battlefield 2.

The relationship with DICE was short-lived, as Trauma got shut down less than a year later in 2005. But THQ, believing it needed a presence among military shooter games to keep its top-tier publisher status, recruited the core Trauma team in 2006 to found Kaos Studios in New York City. Kaos got to work immediately on Frontlines: Fuel of War, which shipped on Xbox 360 and PC in 2008 to squarely average reception.

By 2008, the first-person shooter genre was quickly heating up, getting more competitive and more expensive. Yet as Call of Duty games reliably reached unprecedented sales successes, most publishers saw competing in the genre as increasingly risky.

THQ had just established its "pillar" strategy, under which an entire arm of the company would be devoted to core games, and leadership of that branch was given to Danny Bilson, a writer and director with Hollywood roots who became core games' EVP.

Homefront was to be the crown jewel in THQ's core ambitions, and former Kaos employees say it became Bilson's "pet project", and that despite professing a hands-off creative philosophy in the press he was in fact heavily invested in the game's creative decisions -- sometimes, according to some, to its detriment.

Kaos' studio culture "was the direct result of a group that had made a labor-of-love mod in their spare time [being] handed keys to a studio and... financed to make a game," one former staffer tells us. "Mistakes were made and processes weren't clear, but there was an air that we were all in this because we loved it. As we switched over to developing Homefront, we started to attract more seasoned veterans."

A particularly assertive and savvy recruiter was able to populate the Homefront team with very experienced developers -- in most cases, the new hires had more qualifications than those senior to them. "One of the guys we interviewed had a more impressive resume than my own, but we felt he didn't meet our requirements," says the former staffer. "That told me that if I had the same resume [as when] I applied to Kaos a few years before and came to work for Homefront, I couldn't get my own job.

Another former Kaos employee says that longtime leadership failed to adapt processes for a larger staff and a higher-end product. The highly-qualified recruits came with high salaries and relocation fees, but management wasn't prepared to make the most of that acquisition expense. "They didn't listen to the very talented team they hired," laments the ex-staffer. "You had this level of leads with tons and tons of experience, and you had the directors with much less."

The result of this misallocation of intellectual resources was that lesser wisdom often thrived. Staffers say that the main development of Homefront was actually finished within one year -- with the first two years of its three-year development virtually wasted on ideas that didn't pan out, including nine months spent on a single-player prototype that got scrapped.

Thanks to some mismanagement and emotional tension among the staff after the release of Frontlines, there was high turnover between projects, with the studio's programming talent being hit especially hard. But the biggest loss, according to nearly all the former Kaos employees to whom we spoke, was that among that wave of between-project departures was co-founder Frank DeLise, who is said to have left for personal reasons.

DeLise is described by his former colleagues as the studio's passionate head and heart, and a resolute problem-solver who built the studio from scratch and liked to get as much as possible done with his own two hands. That made the gap left by his departure all the wider, as many claim there was no plan for anyone to adequately take the reins from him.

From there, morale began to suffer, as management structure felt uncertain and weak amid a revolving door of GMs and similar leadership. Many staffers reported an uncomfortable environment where art and design often felt oppositional and adversarial, thanks to a widely-disliked art director who had to be fired in the middle of Homefront. The first general manager hired to replace DeLise also didn't work out. By 2010, one ex-employee estimates that up until the game's Alpha period, Kaos lost about a person per week for about the first 30 weeks of the year.

The source describes a team picture hung in a concept artist's office that quickly became a sea of crossed-out faces as the artist kept track of who had quit.

Then there were the infamous "Davids" -- David Broadhurst and David Schulman -- brought in to fill some of the leadership role. The pair received universally negative reviews by their once-employees: "Under them, it was a tyrannical dictatorship that no person should ever be subjected to," says one. "[Schulman] walked all over people to get to the top, and it wasn't a shock that the studio revolted against him once he got there."

By the time a third David -- Dave Votypka -- was handed the GM role late in Homefront, it was too late for a turnaround; employees describe him as a nice guy who may have been out of his depth: "He seemed overwhelmed almost from the get-go," we're told. Votypka was reportedly so stressed out that he engaged in arguments about the "selfishness" of those who left a clearly-sinking ship for better offers elsewhere.

Amid these management and cultural challenges, the Kaos team still had an enormous mandate: Make a game that could compete with Call of Duty. One ex-staffer says that at one point in Homefront's development, the team made a decision to duplicate the collapsing-bridge Spec Ops mission from Modern Warfare 2 in its own engine to see how close they could get, and where they could improve.

The project was emblematic of core games EVP Danny Bilson's ambitions, and although he only checked in with the team about once per month according to staffers, he did so with a vengeance, becoming passionately invested in creative decisions. "He got very involved during the middle of our production," a source reports. "This game became the title that would prove THQ was on the rebound in a major way."

Employees mainly liked Bilson personally: "I really can't slam the guy," the source adds. "He gave us a great opportunity and all the resources to accomplish it. We didn't exactly deliver."

And many feel his creative input ultimately made the game better -- with one exception. It was Bilson's idea to make North Korea the occupying force of Homefront, despite how unlikely a significant U.S. invasion by such a small nation would be. Most North Korean confrontations with America have been little more than posturing.

The premise was widely questioned in the press, which caused the team some stress. According to our sources, Kaos had originally envisioned the invaders as Chinese, but THQ feared that such a portrayal would hurt its prospects for business in China, which has in recent years rapidly begun offering more and more opportunities for Western game developers.

Kaos suggested a coalition of Asian nations instead, but Bilson passionately preferred the Korea idea, and so it stood. An ex-staffer describes this as "demoralizing," in that the implausibility of the premise felt "stupid" to the team, and it was also frustrating for employees to see most of the press at that stage questioning the idea rather than looking seriously at the game.

Bilson became known as "one of the chief creative guys -- for an hour a month when he would hand out mandates on high and then disappear," according to one source. Employees even coined a sarcastic term internally for Bilson's brief but reverberating check-ins: Getting Bils0wned.

Part of the problem, an ex-staffer says, is that as a "Hollywood guy", Bilson's creative approach didn't necessarily lend itself to game development. "We can see the stuff he was really good at, which was helping guide the story, create hype... if you look at the marketing for this game, aside from the story, it was one of the best marketing campaigns in games," says one staffer, adding that Bilson "excelled" at directorial elements like motion capture shoots and voice-over recording, where he was often present in person.

"On the other hand he's not qualified to talk about game mechanics," the source continues. For example, if Bilson didn't like a gameplay sequence, he'd ask developers why they couldn't "just shoot it from another angle." That made lists of bulleted feedback frustrating.

Another staffer says Bilson's feedback wasn't necessarily harmful to the game, but his public statements were often upsetting to the team. For example, Bilson announced plans for Homefront 2 long before Kaos was near finishing Homefront -- and without giving them a heads up. And when anonymous complaints about intense crunch on Homefront leaked to the media, Bilson's suggestion that long hours were not only ingrained in the studio's culture but also to be expected upset many.

One source tells us the minimal expectations for all members of the studio were six months of 12-hour shifts, six to seven days per week. But actually, according to the ex-staffer, most of the studio was clocking 14 to 16 hour days, seven days a week, during that six-month window. Some worked that schedule for 14 months, and jobs were at risk if the time quota wasn't met.

The staffer describes "inhuman, combative" leadership and labor under a system of fear. Many employees say their health and family relationships suffered -- and hearing THQ execs tell the media that crunch was reasonable and expected felt like a slap in the face, as the crunch came from poor management and an unhealthy environment, not because the work ethic dictated it.

Yet many ex-staffers seem to generally like Bilson: "I think Danny's being crucified a lot and I think that's unfair," one says. "He wasn't necessarily the problem. He had a way of doing things, and he burned a lot of bridges because he was a ballbuster, but if you look at the core games he's done, that's the only thing keeping THQ in business right now."

Bilson also came up with much of the high-level story ideas for the game. Although Red Dawn scribe John Milius is credited with writing the script, multiple staffers tell Gamasutra he ultimately wrote not a word of it, despite the game containing at least 20,000 lines of dialog. Most former employees credit Kaos writer C.J. Kershner with Homefront's script.

This failure to appropriately credit contributors was something of a final insult to many ex-employees once the game was out, as many staffers who left for more secure work found themselves relegated to a "special thanks" section. One former employee who left the project late even says his child was left out of the credits' list of "production babies," a petty slight.

In the studio's last days, the team felt worked half to death and wrung dry, and there was a prevailing sense that there was no way a publisher THQ could keep a studio like Kaos open after Homefront, even though the publisher -- and Bilson in particular -- vouched for the team's talent till the end.

At the point, GM Dave Votypka "had one foot out the door," says a staffer whose opinion is that the final nail for Kaos came when THQ learned Votypka was seeking a better job -- because "there was nobody internally that was going to step up."

THQ brass informed Kaos that its future would depend on Homefront's sales and critical reception. As of the time the studio closed, the game had sold 2.6 million units and had a 71 Metacritic aggregate. "Call me cynical, but I think the plan was was to close the studio regardless," one source says.

But many say they knew the writing was on the wall when THQ began publicizing its new Montreal studio to the press, about six months before Homefront's ship date. Kaos employees watched the studio tour videos online, gazing enviously at a state-of-the-art facility in which the publisher had clearly invested heavily.

"Montreal, which THQ had been hyping for some time, had the potential to become a multi-project development center with a rockstar creative team and the Quebec government offered great tax incentives; Kaos, by comparison, was a one project studio in the most expensive city on the planet," reflects the source.

And Kaos' own studio was rife with facility problems. Employees describe an "absolute dump" where, by the end, some staffers had desks beneath stairs. One men's room urinal sprung a leak, and someone's idea of repair was to stick a trashcan underneath it with a warning sign. One ex-employee estimates the urinal went un-repaired for some seven months, and that the "Urinal Bucket" became something of a symbol for the hopelessness and irrelevance the team felt when compared to THQ's shiny new Canada studio -- the one THQ would soon announce was taking over Kaos' franchise (before ultimately signing Crytek for the sequel.)

The entire triple-A studio, gutted by layoffs and talent drain, found itself with nothing to do but support the game it already launched. It was clear to everyone then what was going to happen next.

"We cost a lot, and we did not meet [THQ's] expectations for quality," one says.

Though many of the former team members we spoke to are disillusioned and seem like they'd be happy never to work together again, there's still a core group of friends sharing positive energy, who say they hope to form a startup together in the near future. "The fact that Kaos was still chugging along, and the fact that it even still had a chance despite all these stupid things that happened, is a testament to how good that core team is," one says. "That team could have gone on to do some great stuff."

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like