Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Three small Facebook game developers share stories of triumph and cautionary tales about trying to survive in a market quickly becoming dominated by companies like Zynga and Playfish.

There's currently a gold rush in the social gaming space. FarmVille has over 80 million monthly active users (MAU) and, late last year, Electronic Arts purchased Playfish for $300 million. Those types of numbers make people take notice. But on a platform like Facebook, which seems to be dominated by a few big games and even fewer big developers, creating a popular game can seem like a daunting task -- especially for smaller, independent studios.

Gamasutra sat down with three different developers to learn just how you can be successful on the world's biggest social network, even if your name isn't Zynga or Playfish.

If you were to pitch a game where the gameplay revolved around setting a trap and waiting for mice to come, chances are most publishers wouldn't bite.

But it was with just such a game that Ontario-based HitGrab Labs was able to achieve its biggest success: MouseHunt. After getting started doing online marketing, HitGrab eventually made the shift to Facebook development.

"We took on a job where one of our clients... wanted a Facebook application," says HitGrab owner Joel Auge. "So we told them we could do it, though we'd never done it before, and just fell in love with the platform. We did that and we realized very quickly that we weren't really great customer service people. But we really liked the platform. So we decided, 'Why don't we do our own thing?'"

After creating a wedding registry application that Auge says "failed miserably," the studio made the shift to game development in spite of the fact that no one on the team had any game development experience.

"[Executive producer] Brian [Freeman] woke up one day from a dream and he was like 'Yeah, mouse traps. We should have people create their mouse traps 'cause you really just set the bait and then you leave and you come back,' and we were like 'Oh, that's interesting,'" Auge says.

"So we decided to build a game around it. It took us like two weeks to drum up a quick beta, launched it to 40 friends, and their reactions were, like, unbelievable. They were freaking out they loved the game and we decided, 'Let's just be a gaming company.' And MouseHunt's growing to this day, actually.

"From a marketing perspective we kind of knew that we had to build a business first, which helped us a lot, to be honest. We didn't really know what we were doing game wise. I mean, we've all played games. We all have game consoles at home. So all of us play games. You know, our generation does. As far as designers, we really just tailored the gameplay around the platform... To be honest, a lot of the obstacles that we were facing, on scaling and making it interesting, those were things that provided us with new opportunities to come up with new ideas that really haven't been used much on the platform at all."

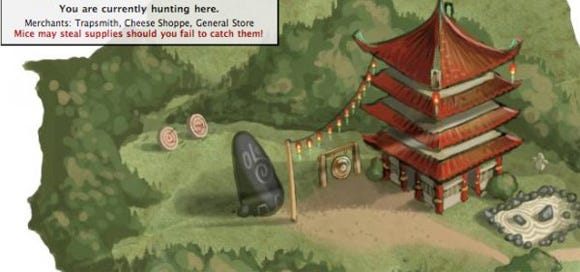

MouseHunt

And Auge says that these "new ideas" are what allowed MouseHunt to become a success. On a platform that's dominated by genre games -- farming, restaurant management, mafia, etc. -- something like MouseHunt is able to stand out.

"To this day, if you were to tell people a mouse game on a social platform is going to do well, they'd probably laugh at you," he explains. "But to be honest I think it's really protected us to a certain degree. What we really tried to focus on was stuff that takes too much time really for the big guys to think about."

This has allowed MouseHunt to garner nearly half a million MAU, enough for HitGrab to survive solely off of Facebook development. And while those numbers may not sound all that impressive, the key to HitGrab's success has been in cultivating a very active audience, something it's been able to achieve via constant interaction with fans.

Every Friday the developers hold a chat with the community where they discuss the game and talk about upcoming content. The die-hard fans who participate in these chats then spread the word to the rest of the community, saving the studio from having to do much in the way of promotion.

"They do a lot of the work for us," Auge says "We take care of them and they take care of us. For instance, we'll have a feature that we'll introduce in our Feedback Friday -- we'll talk about a new area that'll be released next week, and unless you were in that video chat you wouldn't have any idea. So those users then go to the forums and tell all of their friends about these new things that the developers from HitGrab are doing. And that whole process breeds a sense of community."

But despite the success of MouseHunt, HitGrab's second release, MythMonger, hasn't quite caught on the same way, with under 50,000 MAU. According to Auge, this has been a result of not learning from their experience with MouseHunt.

"We didn't really learn the lessons we needed to learn severely enough at the time to implement those lessons from MouseHunt," he says. "For instance, MythMonger is complex. MouseHunt is uber-simple. And that's something we should have taken away from MouseHunt, but we didn't really apply it to MythMonger.

"There are probably too many ideas that made it into MythMonger... But we're listening to the audience now and we're hoping to deliver a better product very shortly. To be honest, it probably comes from a lack of game development experience. A lot of the guys in our field have been doing games for years, on mobile or on consoles, and already have an understanding of all these things. But we're still learning as a company and we're probably never going to stop learning."

In contrast, Broken Bulb Studios, the developer behind Ninja Warz and My Town, did the opposite: releasing a mildly successful first game, followed by a much more popular second release. But, like HitGrab, the studio didn't start out as a game developer. After years creating social network content and Flash widgets and toys, Broken Bulb decided to make the move to gaming just nine months ago, selling off all of its assets so it could be 100 percent devoted to game development. However, Facebook wasn't the studio's first choice.

"We originally built Ninja Warz solely for Twitter," Broken Bulb president Jason Moore explains. "When we started building it it was during the heyday of the Twitter rise, and we wanted get in early and bypass much of the competition on Facebook by trying our hat at more of a new platform.

"When it turned out that platform just didn't have the viral channels to really support a developer community, we decided to port it and change it for Facebook and immediately you could see the difference: we went from 40 sign-ups a day to several thousand sign-ups a day just by switching platforms. So we are on Facebook and developing for Facebook because its the most successful platform, as a developer, to get users."

With Ninja Warz, the studio was able to learn the ins and outs of the platform, and took advantage of that knowledge with the release of My Town. "A lot of it was due to the viral channels -- and we, at our studio, we are really into user experience," says Moore.

"Basically, from Ninja Warz we learned what are all the viral channels, or all the communication channels, that Facebook allowed. And once we got intimately familiar with those, what we were able to do when conceiving My Town was decide how can we use every channel that they offer, but in an organic way that is seamless through the gameplay, instead of just tacking things on," Moore says.

"So we actually ended up building My Town kind of backwards. We decided all the features we wanted to use and integrate seamlessly, and then we built a game around that. That was one of the successful models that helped us build My Town."

Ninja Warz

The game currently has over three million MAU and helped create a new genre on the platform: the town creation sim, which has already spawned several clones. But while players may be looking for new experiences when it comes to Facebook games, the trick is, Moore says, convincing the developers.

"I think that a lot of the success that we've had early on was because it was new and different," he explains. "Where it's a tough sell is to the developers. It's an easy thing to say 'OK, this app is successful, let's just clone that app and I will have a successful app.' It's much scarier to developers to say let's create something new, [to say]. 'Let's create a genre.'"

Says Moore, "We consider ourselves a very original, very user-focused game studio. And so we didn't want to just put out a clone. We could've made a FarmVille clone, but instead we wanted to make a new genre and I think that the users are clamoring for new and different. The problem, and the reason why the top games don't show that, is solely because there isn't new and creative good quality games coming out in new genres as often as there are clones and copycats."

And while having a large player base is obviously good, Moore believes that there is another factor that is much more important to being a successful Facebook developer.

"I think that retention of users is the number one most important metric on any of our games, and that is the number that we try and aim for the most. The only thing that's going to retain players at all is gameplay. If it's a good game users will continue to play. And if it's not, if you've got great viral channels you can get users, but if the game is not entertaining and genuinely fun and built for the user, they will tire and bore of it," says Moore.

"If you're building a game to be a stand-alone, quality game: take all viral stuff out, would people play this game and enjoy it for an entire month? That's the question you have to ask yourself and I think that most of the games, and most of the developers, hinge so much on the marketing and the virality side that it really takes away from their gameplay. So we make sure that our gameplay stands on its own," he says. "The dedicated fan base is the buying fan base."

Of course, while the massive user base and continual growth of Facebook means there is a lot of opportunity for smaller developers, it is in no way a guarantee of success. This is something that Justin Hall, former CEO of the now-defunct GameLayers, knows firsthand.

"We built the first MMO in a Firefox toolbar, The Nethernet, also known as PMOG," or passive multiplayer online game, says Hall. "PMOG/The Nethernet did not monetize well, and it didn't have strong user-to-user growth. So, as our studio funds dwindled, we looked around and said, 'Where can we make games that make money?' We had social game building expertise, and we'd built RPGs before, so seeing the traffic and growth on social RPGs on Facebook attracted us to that platform."

In late 2009, GameLayers released two different games on the platform: Dictator Wars and Super Cute Zoo. But both games only lasted a matter of months, with the studio experiencing issues with two of the most important resources for a small developer -- time and money.

"Both games were fun to make and fun to play," Hall says. "But they were not on track to make immediate profit or keep our company open.

"Running an online game is a commitment. Players have questions, suggestions, feature-requests, and things break as people use them. We couldn't pay our staff to keep evolving our titles, so we decided to take these games down rather than offer continually diminishing service.

"We didn't have a lot of time either; we raised $2 million in 2007 and 2008 and it was steadily diminishing. For both Dictator Wars and Super Cute Zoo, we launched the minimum viable game and planned to evolve them based on usage. So we improved our invitation rate and growth potential and improved the game experience. But the growth we were hoping for didn't come fast enough."

A major problem for developers, Hall says, is that Facebook is changing so quickly that it can be hard to keep up. In the case of Super Cute Zoo, this meant that by the time the game was released, it already felt dated to players.

"Social RPGs are a timeless game form with solid monetization potential, but by October 2009 the big stars of Facebook gaming were all Flash-based titles with more polish and interactivity. With Super Cute Zoo, we offered players a chance to 'collect animals and build your zoo!' -- a game that looked mostly like text and menus, not point and click.

"With tens of millions of people playing FarmVille by late 2009, player expectations had changed, and the female animal-loving market we targeted was excited elsewhere. Facebook as a game platform changes rapidly, like month by month."

Clearly, like any other platform, there are a number of factors that determine whether or not a game will end up being successful on Facebook. Having ample time and funding to let your game grow is important, as is the overall quality of the experience.

But, when asked what advice he'd give potential indie Facebook developers, HitGrab's Auge had one very specific instruction: "I would say hurry, because there's just a tremendous sense that the big guys are coming into the space. I would say, if you're a small indie guy, go after a core audience, be okay about the niche product. Those users will likely pay your bills."

GameLayers' Hall agrees, though his advice is naturally wary -- he thinks that making it big will be a huge challenge. "I think small developers can definitely carve out a niche," says Hall. "If you want a small lifestyle business that supports you and one to three people making games, and making some money from that, and working with your player community, you can have a rich, rewarding social game experience on Facebook.

"You need to be very agile, very fast, and thick-skinned... There's huge potential to design a game that works well within the Facebook network, and it has to be about social interactions between players. So that's an exciting challenge. Small developers who want more than a lifestyle business, where you're growing a games company and supporting payroll and moving out beyond a group of friends, that is a bigger challenge: you have to keep up with some very smart, very fast-moving competitors."

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like