Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

How and why are the major publishers integrating social features into their games? Can game-level social networks become an essential part of the game playing experience? Gamasutra dives in to Halo Waypoint, Call of Duty Elite, DICE's Battlelog, and more.

Fifteen years ago, video games underwent a paradigm shift, migrating from 2D to 3D. In the years since, it's been unclear what the next major paradigm shift would be. Might it be motion controls? Online multiplayer? 3D displays? Could it have something to do with the simplicity of mobile games? Or the social networks that make them available to hundreds of millions of potential players? There is no clear answer to this search -- the truth may be all of these areas of transformation will cohere into something as yet undefined.

The industry's biggest publishers were slow to invest in motion controls and have been even more skeptical about 3D displays, but in the last few years investing in social network games has drawn more and more attention. This isn't just about creating mini-game crossovers that can be used to promote an upcoming blockbuster console release. Instead, it's about rethinking the overall design of a game as a kind of social network of its own, a medium through which people can play with each other, become friends, and share their creativity.

Activision has launched Elite for its Call of Duty franchise, EA has built similar services with Autolog and Battlelog for its Need for Speed and Battlefield franchises, each of which plug into the wider umbrella network that EA uses for all of its online games, regardless of platform.

Microsoft built Waypoint as a permanent home for Halo fans in the Xbox Live dashboard, and Nintendo has even experimented with custom channels for its Mario Kart and Wii Fit games.

Ubisoft has has praised the "socialization of triple-A games" and is approaching it via its Uplay service. The company's recent purchase of Trials-developer RedLynx, as well as its upcoming Tom Clancy's Ghost Recon Online could mark the beginning of the company's new social era.

What are some of the benefits of treating a game as if it were its own social network? Is this a passing phase, or an essential foundation on which the next major paradigm shift in video games will be built?

"We have been creating Battlefield games for more than a decade now, and we felt that we owe it to both ourselves and the community to build a social network around our games that we are in control of and that we can update frequently," Fredrik Löving, Battlelog Producer at DICE, said.

The addition of a social network to long-running game franchises like Battlefield is many ways a matter of developers catching up to what players had been doing on their own. The Battleog launched alongside last year's Battlefield 3 as a browser-based social network that allows players to build profiles, connect with people they've played against, track stats, watch feeds from other people's games, and keep track of leaderboards. Rather than build the service as an app for Facebook, EA and DICE decided Battlelog would work best as a network that stood on its own.

"I believe that people don’t have the same friends on Facebook as they have on Battlelog," Löving said. "Personally, I have lots of friends on Battlelog that I play with every day, and I feel that we are truly friends in the realm of Battlefield 3. However, we are not friends on Facebook, as Facebook to me is more about people I would actually meet face-to-face and not only in the gaming realm."

The decision to make Battlelog its own separate entity -- neither tethered to Facebook, the PlayStation Network, nor Xbox Live -- sets the tone for the whole experience, something that self-contained and isn't set against a background of dinner photos, Spotify playlists, or Netflix notifications. For PC players, Battlelog works as the game's launch pad, a sort of vestibule that filters out everything unrelated to the coming session of play.

"We did a poll and found out that roughly 12 percent of Battlelog users even have Battlelog as their start page in the browser," Löving said. "That made me very happy, since it’s even stronger numbers than the equivalent for Google, Facebook, and other popular start pages."

For many players, the kinds of socializing that happens around and within a game are nothing like the sorts of socializing that happens in Facebook or Twitter. There would be something disjunctive about treating their Battlefield 3 sessions as a subset of Facebook, a separate but equivalent variation on tagging people with notes, posting photos, and making party invitations.

The socializing that happens around Battlefield 3 can be seen as a way of escaping those simpler and more traditional forms of interacting; Battlelog is a social network whose richest interactions ultimately takes place outside of its borders.

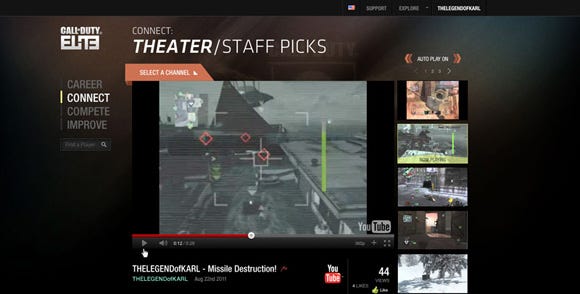

Call of Duty Elite

"I think that's where it gets pretty exciting -- where a social network becomes a network that actually lets you go out and participate in something together," Jamie Berger, Activision's vice president of digital, told Gamasutra in an interview last year. Like EA's Battlelog, Activision launched Elite as a self-contained social network in support of its Call of Duty franchise. The service, which has free and fee-based subscription options, is a stand-alone browser-based social network that directly connects to players' time spent in Call of Duty games.

"One of the most interesting things to me is how positive people are in the service," Berger said. "I'm most excited that within it, people are being supportive; they're actually talking to each other, and amongst each other."

"They're so happy to actually have a place to be part of a community, not a message board... they're actually behaving very much like people who just want to be social and have fun, not people who want to flame each other."

Multiplayer shooters like Call of Duty and Battlefield have also been places notoriously inhospitable to newer players, but the addition of a stand-along social network where player behavior can be quantified and viewed by others in the community appears to have made the communities more cooperative and, in some cases, more hospitable to new players hoping to learn about the game without having to suffer through a game-over screen every 10 seconds.

"It creates a social contract," Berger said. "How can we start behaving as if we live in a neighborhood? You try to treat your neighbors with respect. When you create a true community, that, to me, is the difference between 'social gaming' and a community."

"I'm really excited about that aspect. It starts breaking a lot of the bad assumptions about what a shooter is. It breaks down those anonymous walls and turns it into something where you start knowing each other."

A large part of this accessibility comes from making salient facts about how to best play the game available in a format of passive consumption, where players can benefit from another player's insights without having to compete directly against him or her.

"With Battlelog, we make the product a lot more accessible to non-Battlefield players," Löving said. "By adding a social layer, being on the web and allowing sharing of your gaming experience, it gives everyone a greater insight to what Battlefield is all about."

"What we can clearly see is that for all users, no matter game format, stats are of the utmost importance. People love following not only their own progression, but also their friends and foes."

Services like Elite and Battlelog are still catching up with Waypoint, Microsoft's hub for "all things Halo" launched in 2009 as a stand-alone service for its signature franchise. Compared to Elite, Halo's approach to social networking is more a balance between multiplayer, single player, and crossmedia promotions.

"I actually think of Waypoint like a TV Channel with multiple personalities: one minute it’s the SyFy Network and the next it's ESPN," said C.J. Saretto, Waypoint Lead at 343 Industries. "Halo fans are just as into the games as they are the Halo Universe. Waypoint tries to be a rallying point that connects fans to the Halo Universe, celebrates their achievements in the Halo games, and connects them to other Halo fans."

Halo Waypoint

Though its natural home remains Xbox Live, the network also has web browser, iOS, Windows Phone, and Android versions, making it possible for Halo fans to have a connection to the franchise from almost anywhere -- everything from aggregated player stats across multiple Halo games to behind-the-scenes specials about the making of Halo toys. Waypoint also takes advantage of its symbiosis with the larger network of Xbox Live, which all its portals point back to.

"Halo players are all Xbox Live players, so Waypoint identifies fans by their Xbox Live Gamertag," Saretto said. "Waypoint Mobile also lets you communicate with your Xbox Live Friends List, because we know those are the people you play Halo with."

One of the benefits of working in concert with Xbox Live is the ability to connect fans with the franchise over the course of multiple games so that they can retain a sense of progression and continuity even when putting aside a previous year's title for a newer one.

"We have longtime fans of Halo who often mention how they appreciate that their Career Milestone reflects 'all that hard work' they put in to getting Halo achievements from game to game," Humberto Castaneda, a producer at 343, said. This tracking of achievements from all the different Halo games, which appear as a series of fragmented lists in the traditional Xbox Live Player Cards, get collated into a centralized career list in Waypoint. Think of it as a kind of filter that lets players momentarily strip out everything not related to Halo from their Xbox Live interface.

Though nowhere near as comprehensive an offering, Nintendo has attempted to socialize its Mario Kart games with a simplified version of the network within a network idea. Both the Wii and 3DS versions of Mario Kart have been given discrete channels that allow players to check in on their stats, leaderboards, and upcoming tournaments from the console's boot menu without having to actually launch a game.

This approach offers an ideal compromise for the fact that even the most compulsive games don't reward daily use as consistently as Facebook or Twitter do. In the same way that players cannot live by Halo or Call of Duty alone, creating system-level hubs for longtime players to stay connected to the community while on their way to doing something else is a powerful retention tool, keeping the game's newest updates, tournaments, or high scores fresh in players minds even while having another game disc in the machine.

The early success in connecting hugely popular game franchises to social networks of their own will inevitably prove to be the exception and not the rule. When there are only a handful of channels, apps, and widgets to sort through, social features seem like a great idea. Imagining a future where every major game launches with its own stand-alone iPhone app, browser-based stat tracker, and channel would quickly transform the whole socialization movement into an overexploited clatter of empty vestibules blinking loudly for attention.

Not every game (or even franchise) deserves a Waypoint. Even still, many games might be improved by incorporating some of the lessons learned from social networks to help them cut through the chaos of the market.

"When we looked at integrating social networking into SSX we asked ourselves how we could enable players to create interesting content for other players in our game," Todd Batty, creative director on SSX, said. "The richest social networks tend to be the most dependent on the people who belong to them to make interesting and meaningful content for other people on the network."

SSX did not launch with a social network or system-level channel, but the idea of using player creativity and competitiveness to keep others returning to the game plays a central role. Borrowing from the Autolog feature EA has built up with the last two entries in the Need for Speed series, SSX uses Ridernet to asynchronously link players to the achievements of others in their friends list.

"We have a ghost system in the game, so if I play the game a lot and post a lot of my ghosts around the world then I've created something for a lot of my friends to compete against, which, by virtue of being there, make the game a richer experience," Batty said.

"We also have a feature called geo-tagging, an online kind of hide-and-go-seek where I can go anywhere in the world I want, hide the tag somewhere in the 3D space where I don't think anyone will be able to find it, and then see if other people can go find it. So I'm creating interesting content for people while I'm playing the game and having a good time on my own."

Underneath these features is a competitive wagering system where players can challenge each other using an in-game credits system. If you post a geo-tag, for instance, you can bet a sum of credits that no one will be able to find it. If some finds it immediately, they'll get all of the credits, but if it takes them a long time you'll get most of the credits.

"That right there is what makes a great social network: everyone is motivated to do something, and that thing makes the whole experience richer for everyone else," Batty said. "Any social network -- whether it's Facebook, Twitter, or a video game -- every single one of those relies on that formula."

"Some games talk about social features and have ways to meet up with friends and play against them, but they don't have that same means of creation and consumption in that loop, and so the entire social network falls apart. If you don't have interesting and constantly new creative content, the whole thing will fizzle out and die."

Ubisoft has embraced the idea of asynchronous social play in favor of building new social networks from scratch to support their major franchises.

"The idea is that triple-A games can really benefit a lot from the revolution that's happening around us," Yves Guillemot, CEO of Ubisoft, said in an interview last year. "At Ubisoft, we already have games on the way that take advantage of asynchronous gameplay, the fact that you are connected all the time, and the tracking system that can actually give an experience that is more adaptive to each player, and also to his friends. So we can give the gamers the possibility to play alone, but also with his friends if needed."

The benefit of social networking ideas can be best implemented in overarching goals that don't necessarily interrupt the moment-to-moment gameplay, but rather affects the larger purpose players are trying to achieve through it.

"Imagine you have to decrypt a language," Guillemot said. "You're in a world, there's a language, so it's either a language that has been decrypted by specialists, or it's a new language that we've created that's to be decrypted that needs a certain number of competencies. If you decrypt the language, you will be able to discover a place in the world, and discover treasures and different civilizations."

"If the group is capable of decrypting that -- you can still play normally [alone] -- but you can do it with friends who can help decrypt it. And then they can take advantage of this, to go and fight other groups. We can stop being alone when we play, and play with friends who prepare something to help you succeed. And then that group who wins can be against other groups that will have other advantages and influences. The potential is just infinite of what can be done."

Perhaps the biggest benefit of increasing social ties in games come from the heightened connection between player and developer, offering a way for developers to better understand how their game is being played. "It has been a very interesting journey so far, and we learn new things every single day thanks to Battlelog," Löving said.

"We have never been so close to our consumers as we are now."

And that, finally, is what makes the addition of social features and social thinking into triple-A games so valuable. It is not just a means of adding a feature to a list or giving business development a new buzz word to bat around the conference room. It is about forming an even closer bond between people who love making games and people who love playing games. The closer that relationship, the brighter the future will be.

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like