Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Capcom's Mega Man 9 is, surprisingly, an intentionally NES-styled downloadable game - producer Hironobu Takeshita explains the artistic and design choices behind a retro franchise renaissance.

Hironobu Takeshita has an interesting job. He's the producer for what is, for all intents and purposes, a NES game. But he's the producer for a brand new NES game in 2008 - Mega Man 9.

Capcom has returned to its roots and created an all-new sequel to its popular franchise, originally created by Keiji Inafune in 1987, and which experienced the height of its popularity on early console systems such as the NES.

What better way to satisfy the fans, then, than to create a new game that strictly adheres to the limitations of that classic hardware, but release it on PlayStation Network, Xbox Live Arcade, and WiiWare?

Speaking in-depth to Gamasutra, Takeshita speaks to the difficulties (and freedoms) that creating a true retro experience creates, and to his vision for a future in which creators can design games based on their artistic choices, not externally-applied pressures of matching up to the standards of contemporary console releases.

I think this is the first example of a developer making a truly retro game for a new download service. I was wondering if you could talk about where you guys got the idea from originally to do that.

Hironobu Takeshita: First, I'd like to thank you for asking me this question - why we decided to bring this back and go with the retro style. As you know, [Capcom head of R&D Keiji] Inafune... Mega Man was one of his first games, and he's always wanted to bring it back. There just hasn't been a chance to do so yet.

Mega Man is a simple game, but it's one that you can get into quickly and really enjoy playing it. We wanted to bring that to a new generation of gamers. Fortunately, now we have download services where we could bring it back. So we thought, "This is the opportunity to do this. Now that we have a method for delivering the game, we should try and see if we can do it - go all the way back to the retro style."

Especially now, retro games are being evaluated as good games. Not all of them are good, but some of them are being evaluated as good games. Since the generation now may not be as familiar with those games, we thought it's time to introduce them to that style of gaming. Mega Man is just the perfect game for doing that.

Many of the techniques that were used to create games in the Famicom [NES] era have essentially been lost, or they're not at all similar to the techniques that are still used. How are you able to make a game that so convincingly evokes that style of game on a technical level - that really does feel like a Famicom game - using modern techniques that your developers are familiar with now?

HT: First of all, we made this game in conjunction with [independent development studio] Inti Creates. Most of their staff used to work for Capcom, and they were involved with the [GBA] Mega Man Zero and [DS] Mega Man ZX series, so they're pretty familiar with this style of game. A lot of them also worked on the 8-bit and 16-bit games back in the day, so they had the experience and the know-how for making a game like this.

Of course, the technical aspects were a little harder, especially with the graphics. Mr. Inafune wanted it to be simple, like the old, early Mega Man games, but the staff, for whatever reason, kept making it more complex.

The details in the graphics were just too much for what an 8-bit game was, so he had to tell them to redo almost half of it at one point, because they were making it too complex. He said, "Make it simple. Bring it back to the basics."

The sound was also difficult to do, because you're limited with what you can do. To go from doing big sound scores for modern games to a smaller sound scale, that was harder to bring it down to the 4-bit sound and using the type of rhythm for the game.

The tools that were used to create this game aren't actually the same tools that were used back in the '80s and early '90s to create these games. What kind of tool was used to compose the music? Was it a Famicom sound emulator? And to create the graphics, what kind of tools were used?

HT: Yeah, the equipment used to make the Famicom games really doesn't exist anymore. We don't have access to that. We have to use modern equipment to make this game. The point is, you have to limit yourself. That was the hard part.

But it was the sensibilities of the staff that were able to recreate that 8-bit feel, because you can go really far with today's equipment. So it was the staff that brought it back to the basics.

Essentially, this game isn't actually a Famicom game. If it were burned to a cartridge, it wouldn't actually run on a Famicom. It is a duplication of the Famicom capabilities, but within a modern game engine and technology.

HT: Well, when you put it that way... (laughter) This couldn't fit on a Famicom cartridge. It's too big. It's too much for that. It's really emulating the old style of games. But we're hoping that when people play, they feel the same nostalgia that they have when they play the original games.

You talked about how people were trying to graphically exceed the capabilities of the Famicom, but what about the temptation to exceed some other capabilities, such as flicker, slowdown, sprite limits, and stuff like that? Was it really hard to get people to stay within the confines of what they could have done, if this had come out after Mega Man 6 in 1993?

HT: Yeah, there were some things, like you couldn't have more than three enemies on the screen at once, so we had to make sure that that's how it stayed in our game. In the part with the dragon with the flame, [there should be] flickering, and whatnot.

In the options of this game, you can adjust that, unlike the old games. We purposely put some of those old-school bugs into this game, so it does recreate that feel.

That's amazing. When you're working on this game and working with the staff, a lot of developers have told me that on the one hand, limitations limit you, obviously, but they also free you in the sense that once you have a set of limitations, you can be really creative about what you do within those limitations. Have you found that that's the case when working on this game?

HT: You definitely could say that. As I said before, Mr. Inafune had to tell us to redo half of the characters. He brought us in the room and said, "These characters are too big and bulky, with too many lines. We want to keep it simple."

Showing us how to keep it simple opened up a new world for us. We could see how the simple characters look better, and you can just picture how they move. He really brought that to life for us. Even though the characters are simple, they still stand out. They still make an impression on you. And I think that's what was important.

For the team, when they realized that, they were able to bring their sensibilities to the game. We are limited, but in that sense, it did open up the creative tunnels.

Like I said, this is the first time anyone's made a new game for download that actually completely looks like a retro game, without any differences. Why do you think that Capcom was the first one to tread that ground?

HT: That's a very good question to ask. There are a lot of reasons. Capcom's got a lot of classic franchises, and each of those franchises has its own set of fans who are really into that franchise. We always hear from those various fan bases, "Why don't you make another one of these games? Why don't you bring this game back?"

Of course, we think about that, and it is a consideration for us, but when you consider modern games that come on discs now, you need good graphics, you need online play, and things like that.

You can't really go back when the expectations are for something of that caliber. But now that you have downloadable games and people are more forgiving of what you can download, they're like, "Oh, it's a simple game, but it's a download game. That's okay."

So we thought, "Well, retro games seem to be what people want, but people want a new Mega Man game. They want another story. But at the same time, they also want the classic feel." To marry those two together was kind of a challenge. We thought, "Are we up for this challenge? Maybe we can actually surprise the fans and deliver what they want. This is what we're going to do."

Did you go through any of the old games and replay them with the developers for reference? Did you just try to remember, or did you actually go through and reference the old games to see what had been accomplished in them before, and where you could jump off of?

HT: Yeah, we replayed the old games. Specifically, Mega Man 1 and 2, because that is the basis of Mega Man 9. It's almost as if Mega Man 9 is the new Mega Man 3, because we wanted to surpass what we did in Mega Man 2.

Mega Man 2's got a lot of fans. Fans of the series like that one the best, so we wanted to try and surpass their expectations for this game. So we played Mega Man 2 a lot to get the inspiration for this game.

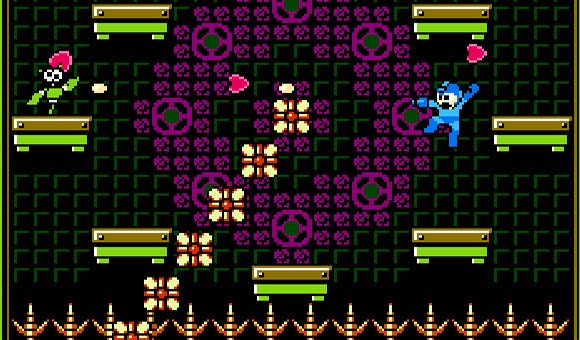

Left: Mega Man 2 (1988), Right: Mega Man 9 (2008)

Did you work at all with feedback from fans and what they've been wanting for years? Did you work with any old comments from when the series was still active on the Famicom? How did you incorporate fan desires in this game?

HT: We're always keeping track of the fans' comments and what they say about the games, and we pay attention to that when we are making the games. For this one, Mega Man 9 wasn't so much about getting feedback for making this game.

The past comments did impact the decision to make this game, and now that we have Mega Man 9, once we put it out, we want to see the fan reaction to this, and that will give us an idea of where to go from here.

Who do you think is the audience of this game? I was 10 when the original Mega Man came out. I was a really big fan of the series on the NES, and now I'm 31. Am I the audience for this game, or are kids who are 10 now the audience for this game, or is it both? And how does that affect how you make the game?

HT: Well, if I had it my way, I'd like to reach both the age groups, but really, this is for the people who played it back then. Now they're older, of course, but this game is for them. We hope they can remember the fun they had when they played it in their childhood, and that by playing it now, they recall that, and it's still just as fun to them.

Now there's a lot of gamers in their 30s and they probably have kids of their own, so we hope that maybe Mega Man becomes a family experience for them. The parents can introduce the games they played to their children.

And you're able to rerelease the old games at the same time. Mega Man 1 and 2 are coming to the Virtual Console. It's a whole way of reawakening the brand. The current, new Mega Man games, especially Battle Network and Star Force, are quite different than what we remember, so this brings the series back to its roots, I guess.

HT: Yeah, there are plans to bring Mega Man 1 and 2 to the Virtual Console. We're not exactly sure when that will happen, but we want to do that. With this and Mega Man 9, hopefully it brings Mega Man back to the fans, and it's something a new generation can also enjoy.

Koji Igarashi, who is in charge of the Castlevania series, is a very strong believer in 2D gaming. He also likes to make sure he can cultivate these design techniques in his staff so they're not lost. As we talked about, this game features design that hasn't been done for some time. Do you think it's important to keep the classic style of designing games alive? Do you feel there's something intrinsic to that that is important to preserve and continue alongside things like next-gen games?

HT: I like to think of it not as an 8-bit style, but more of an artistic choice, if you will. It's another type of creative expression, because nowadays, everyone wants surround sound and 3D graphics and things like that, and they get too caught up in that.

HT: I like to think of it not as an 8-bit style, but more of an artistic choice, if you will. It's another type of creative expression, because nowadays, everyone wants surround sound and 3D graphics and things like that, and they get too caught up in that.

I don't think it should be that way, because you could do an 8-bit game. You can do a 16-bit game. You should do whatever is creatively expressive and what you want to do.

I think that will open up the whole gaming world in general, by being able to have these creative outlets.

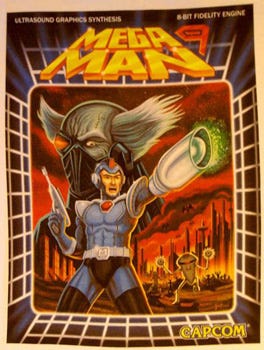

One thing I noticed is that your T-shirt has ironically bad artwork on it. I don't know how long you've been at Capcom, but when American games used to have bad artwork on the cover that was different from the Japanese art, what did you think about that?

HT: That art was very terrible. (laughter) It was atrocious. I'm happy that gamers back then were able to look past that atrocious art and find these good games and were able to enjoy them. We appreciate that.

Looking back, that stuff is 20 years old now, so we can look at that art and laugh at it. Even us in Japan, we laugh at it too. We thought about it and were like, "Yeah, let's do something like this." So Capcom of America came up with the design for us, and then we made these shirts in Japan.

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like