Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Can new developers find success in the post-notifications era of Facebook? We've got three resounding affirmatives from two developers and a consultant, and we explore their paths in this Gamasutra feature.

[Can new developers find success in the post-notifications era of Facebook? We've got three resounding affirmatives from two developers and a consultant, and we explore their paths in this Gamasutra feature.]

While conventional wisdom says one needs the sort of massive hits that Zynga and CrowdStar generate to be really successful on Facebook, that's "total nonsense," says one consultant -- and developers concur.

Rather, in today's market, a great game that targets a smaller, dedicated, niche audience can bring in decent money.

Indeed, developers say, within the last year, the pendulum has begun swinging away from the so-called "soccer moms" -- who gravitate towards casual games -- back to the more traditional core gamer. And savvy small-to-mid-sized developers are creating the sort of deeper, more strategic games that appeal to them.

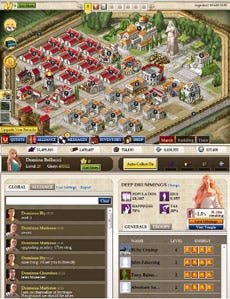

For instance, the Facebook portfolio at Redwood Shores, CA-based Kabam consists mainly of what the company is calling "massively multiplayer social games," while San Francisco-based Casual Collective is creating Facebook games for the sort of hardcore gamers who enjoy a good Call of Duty match.

None of this surprises the folks at Facebook who are recognizing the phenomenon -- and, in fact, Facebook CTO Bret Taylor reported on how small-to-midsized social game developers can be successful on Facebook at the recent Inside Social Apps conference.

According to David Edery, principal of consulting firm Fuzbi LLC, "What we're seeing is the smaller, more targeted games growing considerably faster than the 'big mommas' that appeal to the large, general audiences, like CityVille and FrontierVille. If you believe the statistics, the top five games seem to be losing users while the games ranked 51 to 175 are growing substantially over last year."

Especially, he says, the targeted games that do a good job of promoting themselves in communities that would be specifically interested in the content. "It stands to reason that if you make a terrific soccer game and you advertise it in blogs for soccer fans, you better damn well believe you're going to have a better pass-through and better retention than, say, a FarmVille that appeals to -- who, farmers?"

FIFA Superstars

He cites EA Sports' FIFA Superstars -- currently ranked #62 -- which, he says, "is getting 594,000 daily active users, according to AppData, which is a pretty good number. With anything over a few hundred thousand, you can make some really significant money."

But the majority of Facebook developers don't understand the opportunities available to them by narrowly targeting their games, Edery says. Many of them can't even get their heads around the concept of free-to-play games, he adds. "That's still very hard for most developers to accept -- the idea of giving a game away for free, treating it as a service, and trying to make money over time, not immediately."

Edery spoke last year about how Facebook developers can make money "at the lowest reaches of popularity."

In other words, he says, if a game is ranked #163 on Xbox Live, for example, "you are hosed. It means that maybe five people a day are playing you. Same with PSN. But, on Facebook, #163 might have a daily average user level (DAU) of 50,000, which means you have a good chance of making money. That's an astonishing statistic.

"So what I'm saying is that if that game is designed correctly, if it is monetized correctly, it can make $200,000, $300,000, even $500,000 a year. That's totally feasible. Facebook is one of the only ecosystems where you can be that far down on the chart, and still be making a good profit."

At Kabam (formerly Watercooler Games), the five-year-old developer's three Facebook games -- Kingdoms of Camelot, Dragons of Atlantis, and Glory of Rome -- are doing considerably better than that. Its oldest game -- Kingdoms of Camelot, launched in late 2009 -- currently has a monthly average user (MAU) level of roughly 5.8 million.

"That's in the realm of sales for blockbuster console titles such as Call of Duty: Black Ops, Halo Reach, and Starcraft," says Andrew Sheppard, chief product officer. "That's why we're so bullish on this market opportunity."

He would not, however, reveal figures on Kabam's sales or profits.

Last month, Kabam announced that it had raised $30 million in a third round of funding to develop new games -- and maybe make a few acquisitions. Those new games, says Sheppard, will all be in the same realm as its previous three -- massively multiplayer social games (MMSGs) for hardcore gamers who play on Facebook.

Sheppard expects the additional funding will enable Kabam to increase the frequency of its game releases -- from one every three to four months to one every one or two months.

And, he says, even though Kabam has grown 10 times larger over the past 12 months -- to a staff of 230 -- he expects the aggressive growth to continue both in California and in their Beijing studio. "People who are passionate about building core game playing experiences should know that we have plenty of open roles."

"We've pursued a distinctly different strategy than other social game companies," he says. "Rather than target casual players, we are focused on creating a new segment of games that appeal to a more core gamer demographic. MMSGs combine the deep, immersive gameplay found in MMO strategy and role-playing games with the social connectivity and interaction provided by social platforms like Facebook."

Unlike casual social games -- where interactions only occur out of game when players request assistance from friends -- MMSGs provide synchronous gameplay, adds Sheppard, "where people play with and against other players in real time in persistent game worlds inhabited by millions globally. They also feature real-time chat."

Unlike casual social games -- where interactions only occur out of game when players request assistance from friends -- MMSGs provide synchronous gameplay, adds Sheppard, "where people play with and against other players in real time in persistent game worlds inhabited by millions globally. They also feature real-time chat."

Sheppard believes companies like Zynga, Playdom, and PlayFirst -- which he refers to as "the first generation of social game companies" -- trained a whole new generation of gamers on Facebook, many of whom had never touched a game before, in what has become known as a social gaming convention.

"But that audience of casual gamers is thirsting for deeper, richer gameplay experiences," he adds, "and that's basically the audience we're targeting." He describes Kabam's core demographic as being mostly 25-plus males compared to the 40-plus females who play Facebook's casual games.

Those casual games -- like the ones created by Zynga -- are "very much asynchronous experiences that are gated with just your network of friends on Facebook … and they are designed for short, bursty sessions of gameplay -- perhaps five to 15 minutes -- that is rather shallow and not that deep," says Sheppard.

"Our MMSGs feature synchronous gameplay with tens of thousands of users actively participating with one another in sessions that are hours long, very similar to those of World of Warcraft.

"What is ironic is that Zynga is referred to as the leader of social games, but when you really look at their games, they aren't any more social than WoW. In fact, they are actually less social; their games force you to use your friends to gain advantage in the game," he adds. "That's not our approach at all."

Meanwhile, three-year-old Casual Collective, too, is taking aim at the more traditional gamer "instead of going after the same piece of the pie that others are after," says CEO Will Harbin. "I mean, there are so many FarmVille rip-offs -- or, at least, games with similar mechanics -- that we decided to take a more traditional approach to game development on Facebook. We're going after the user who CityVille really doesn't appeal to."

Harbin believes his core audience is the traditional hardcore gamer -- about 80 percent male and, of those, 60 to 70 percent in the 20 to 40-year-old age range. In order to cater to that demographic, his team has repositioned its most popular game, Backyard Monsters, in the past few months, "making the monsters more cool-looking and less fluffy and cute, adding a bit more violence, and so on," he says. "The result has been higher user numbers for the audience we're after." He says he'll keep that in mind as new games are released.

Casual Collective has two games on Facebook -- Desktop Defender and Backyard Monsters -- with its third, Battle Pirates, currently in alpha but poised to launch a public beta later this month.

"We're loading Battle Pirates up with cool-looking fleets of ships, missile launchers, rockets, guns, ripper cannons, things like that," he reveals.

While Harbin, too, chose not to reveal actual dollar figures, he says he is very pleased with how Backyard Monsters is doing. "It's probably making more [average revenue per user] than CityVille but less than Kingdoms of Camelot.

"What I can say is that it's been meeting all of our growth targets; we're close to about 900,000 daily active users. I expect that it will peak at around 2.5 million in another few months as long as everything continues to go as planned. In addition, we have close to a 30 percent ratio of DAU to MAU; I don't know of any game at that scale that has anywhere close to that engagement."

The bottom line, says Harbin, is that a developer doesn't have to be in the top five or even the top 10 to be a success on Facebook.

"Because Facebook is huge -- with at least 700 million registered users -- you can build a very successful company with just a few million monthly active users," he explains. "You don't have to be a Zynga, even though I'm sure everyone wants to be the one to knock them out of the pole position. There's a lot of open space for developers to capture the more traditional gamers -- users who are used to playing Xbox 360 or PS3 but now want to have a similar experience in a mobile, more accessible environment."

Backyard Monsters

Fuzbi's Edery shares very similar advice with developers anxious to succeed on Facebook but who are finding it's not as easy anymore to get the attention of users.

"Not only have Facebook's viral channels been crippled, but you are competing against big venture-funded companies, as well as publishers, that are spending millions upon millions on advertising to suck up the eyeballs," he says.

"What I recommend is focusing on an under-served niche," he explains. "If no one else, for example, has a great submarine game, that's what you need to make. Then go to all the submarine fan sites and announce that you've got a great new game and to come check it out. That's a much easier path than trying to build the next CityVille that will appeal to 100 million users.

"Hey, if you think you can create the next mega-hit, knock yourself out!" he says. "But just understand that you're competing with big companies with lots of money to spend. Just recognize that you're picking a big fight!"

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like