Games from the Trash: The History of the TRS-80

Radio Shack's first computer was an underpowered but accessible and affordable unit -- and as with nearly any platform, quickly became home to games. In this retrospective, Gamasutra pays homage to a system beloved by many but mostly forgotten by everyone else.

November 26, 2012

Author: by Dale Dobson

Radio Shack's first computer was an underpowered but accessible and affordable unit -- and as with nearly any platform, quickly became home to games. In this retrospective, Gamasutra pays homage to a system beloved by many but mostly forgotten by everyone else.

The TRS-80 Arrives

In the mid-1970s, computer games as we know them today didn't really exist. There were coin-op arcade games, of course, just making the transition from analog circuitry to digital. And the likes of Adventure and Hunt the Wumpus existed on mysterious, arcane mainframe computers locked away on college campuses, likely plotting to take over the world.

There were "home computers," sold in kit form by companies like Heath Electronics, Ohio Scientific Instruments, and the Apple Computer Company. But these machines were the exclusive domain of the hardcore hobbyist armed with a soldering iron, a wire-wrapper and a thirst for technical knowledge.

A nascent support industry provided reference manuals, tip sheets and technical utilities; pre-packaged consumer software accounted for only a tiny fragment of the market, as most users simply preferred to write their own programs.

The executives at Tandy Corporation's Radio Shack division, including buyer and TRS-80 designer Don French, were in a unique position to observe the coming computer revolution. As more and more hobbyists hit the company's small shops looking for transistors and tools, it's likely that sales data contributed to the company's decision to introduce the TRS-80 Model I in August of 1977. Unlike most of its competitors, the new machine was a pre-built home computer, following the Apple II introduced earlier that same year.

Like many Radio Shack products, the TRS-80 (often referred to as the "Trash-80" by fans and detractors alike) cut a few corners to balance price point and feature set against Tandy's profit margins. Features like additional memory, a numeric keypad and lowercase characters were sold as optional upgrades. The system was also notorious for its ability to interfere with local electronics, prompting the FCC to require some design changes by the time the improved Model III was released.

But Radio Shack had a marketing advantage over Apple in 1977 -- its existing stores provided a readymade distribution network, and as commercial software publishers began to emerge a few years later, many companies favored the TRS-80.

The TRS-80 was hardly a gamer's dream; it was designed for "serious" home and business use, though users were hard pressed to find many practical uses for the primitive technology -- a 3 x 5 card and a pencil were still superior tools for most purposes. Radio Shack wasn't quite sure how to market the system to consumers beyond the type attracted by its basic technological appeal, usefulness be damned.

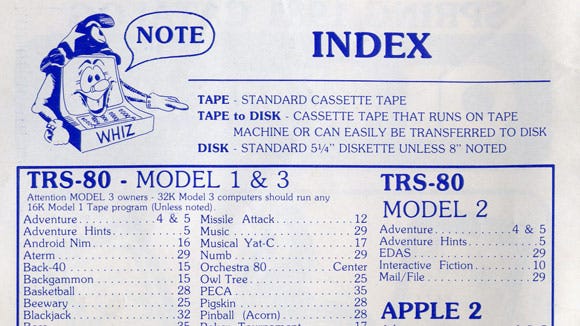

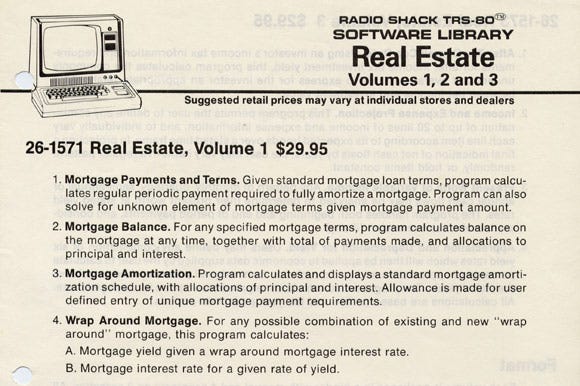

While the TRS-80 was intended to help file recipes and balance the household checkbook, good tools for actually doing so were slow in coming, and most required the additional expense of a disk drive. Many of these utilitarian software packages were promoted with appropriately dull black-and-white one-sheets -- three volumes of Real Estate software, anyone?

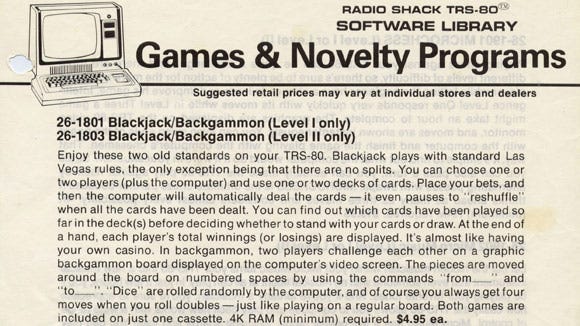

It's hard to believe from a 21st century perspective, but Radio Shack's marketers didn't quite grasp the appeal of games as a way to sell home computers. This ad promoting a paltry launch selection of "Games and Novelty Programs" is just as uninspiring as the company's other software promos:

Rather than focusing on games, it seems, Radio Shack thought they could market the TRS-80 to kids by licensing Superman from DC Comics, and forcing him to pitch the system in a giveaway comic book. This could have been a good idea, had it not misfired badly with a story about two kids helping the brain-addled hero fight a supervillain's flood disaster... by doing a whole bunch of math problems quickly and accurately with the TRS-80.

Fortunately, more entrepreneurial types realized that computer games were an exciting new concept that could survive and even thrive on a platform with limited resources. While the Shack was slow to add games to its official catalog, an army of enterprising programmers started putting the TRS-80 to more entertaining use.

The system's core Zilog Z-80 microprocessor had some arcade credibility -- it was used as the main CPU in a number of early Namco coin-ops, including Galaxian and Pac-Man. But the TRS-80 had limited graphics capabilities -- 128 x 48 strangely rectangular pixels, which could be displayed in binary black-or-white and no grayscale -- gave it a distinctive look. The machine's complete lack of onboard sound didn't help, and there were no official input peripherals available beyond the keyboard, mounted above the motherboard in the same gray plastic casing.

On the other hand, the TRS-80's 64-column text display and dedicated monitor were clear and readable, well suited for text adventures and mainframe game conversions. A complete screen display consumed only 1536 bytes of memory, and text and graphics could be freely mixed onscreen -- something the competing Apple II couldn't handle in its high-resolution mode. And as game developers embraced the TRS-80 and all of its technical limitations, hardware hacks and software tricks soon emerged to advance the state of the art.

Early experimenters leveraged the system's predilection for radio interference to create music of sorts, broadcasting modulated noise to a portable radio placed near the keyboard. Later, it was discovered that the system's cassette tape interface could be controlled directly to produce sound effects -- with an external speaker attached. And several companies adapted the classic Atari 2600 joystick to work on the TRS-80 via the system's expansion connector.

As time went on, clever programmers found ways to produce music in multi-part harmony, parallax scrolling, and even a few gray shades (via a flickery timing trick that few designers ultimately chose to use for actual games.) While the TRS-80's lifespan was relatively short, these community efforts helped make it popular enough to inspire clones in some territories, like the Australian System 80.

The Notable Games

The TRS-80 had amassed a sizeable game library by the early 1980s, but few of its titles are regarded or played as classics today. The system's market penetration was too shallow, and the technology too primitive, to inspire nostalgic memories on the Atari scale. But Radio Shack's machine served to introduce mainframe computer games to a wider audience, supported arcade-style games with some success, and provided an inexpensive, readily accessible sandbox for new ideas.

Many long-running concepts and genres first appeared on this early personal computer, along with a number of experimental dead-ends. Few of the rules of game design were established in 1977, and with low hardware costs and no formal barriers to market entry, the TRS-80 proved to be a great launching pad for budding designers and publishers. By 1979, a few certifiable classics -- or ancestors of such -- were available.

Temple of Apshai (Automated Simulations, 1979)

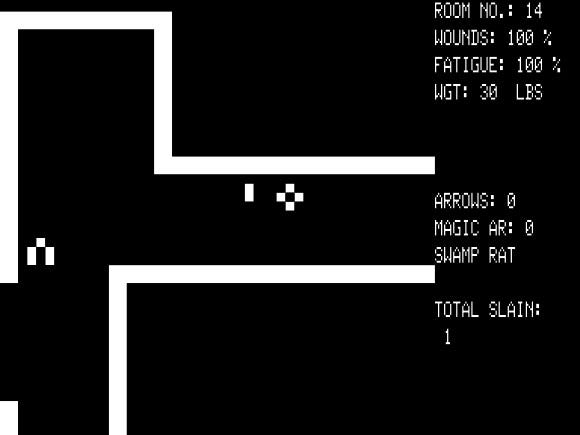

Retro dungeoneers of a certain age will recognize the Apshai series by name, although this screenshot from the original TRS-80 version published by Epyx forerunner Automated Simulations may not look familiar. Slow, clunky and crash-prone, with graphics running at half the TRS-80's normal resolution for the sake of squaring the pixels, this early attempt at an action role-playing game managed little of either.

Item names were abstract (it's the fabled TREASURE #17!) and objects of interest were simple blocks. Enemy creatures didn't look much different from the player, so text at the side of the screen display was employed to indicate just what variety of foe had appeared. The game's innovative line-of-sight effect took forever to calculate, exacerbated by the frequent screen redraws as the player explored the dungeon, step by painful step.

But this newfangled ability to do just that -- stepping through the dungeon, bringing an invisible bow and sword to bear, dealing invisible wounds to nondescript enemies in featureless hallways -- was quite clearly compelling. The dungeons of Apshai would spring to memorable life on future Atari and Commodore hardware.

Eliza (1979)

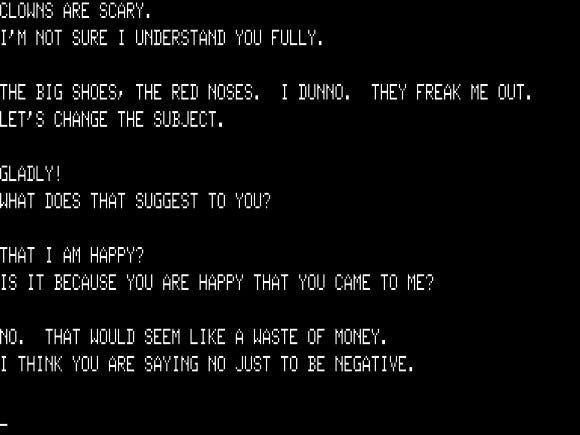

Joseph Weizenbaum's classic artificial intelligence fake-out originated on mainframe computers in the mid-1960s, but a wider audience was introduced to Eliza in the late 1970s on the humble TRS-80. Eliza's conversational abilities would never pass the Turing test -- the illusion was pretty convincing for a few minutes, but quickly faltered as her responses became more obviously repetitive and derivative. But Radio Shack clearly felt she had commercial potential as a technological novelty. Eliza was also one of the few programs designed to use the TRS-80's advanced phoneme-based speech synthesizer -- though a therapist that sounds like the Wizard of Wor may not have offered much comfort.

Scott Adams' Adventures (1978)

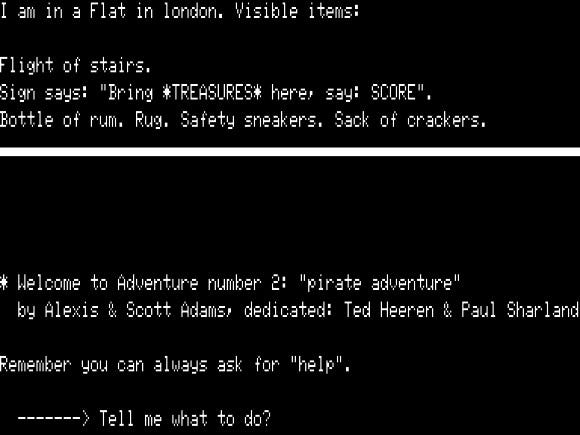

In sunny Florida, computer programmer Scott Adams encountered the classic Crowther and Woods Colossal Cave text adventure game on mainframe computers, and was inspired to bring the game home. His attempt to convert the code to the 16K cassette-based TRS-80 failed (his company would later publish a version for the disk-based Apple II), but Adams' efforts along the way led to his own wildly popular series of text adventure games.

It was the right type of game for the hardware of its day; Adams' parser was efficient, if limited, and his puzzles were clever and leavened with humor, featuring varied and innovative themes and plots. He also did the budding industry a great service by publishing an early BASIC version of his code in BYTE magazine.

Proceeds from Adams' first game, Adventureland, helped establish Adventure International as one of the first large-scale, multi-platform publishers, and he also pioneered the concept of the "game engine" -- with a standardized data format and no graphics to worry about, reaching a broader market was just a matter of porting the original TRS-80 engine to more machines.

The classic Scott Adams Adventure series eventually ran on just about every home computer on the market -- circa 1981, these games were available for the Apple II, Commodore PET, Atari 400/800, and the obscure Exidy Sorcerer. Adams' influence on the adventure game genre is visible throughout the early 1980s; many authors borrowed his characteristic phrasings ("Everything spins around and suddenly I'm elsewhere..."), and some even reverse-engineered his data format to create their own games and engines.

Zork (1980)

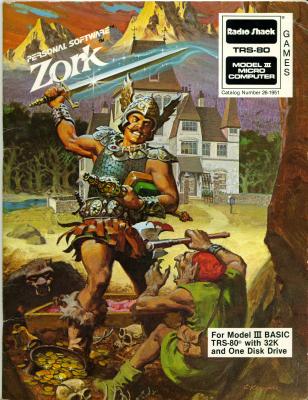

Everyone knows about Dungeon, a.k.a. Zork, the seminal work of interactive fiction created by Marc Blank, Dave Lebling, Bruce Daniels, and Tim Anderson on MIT mainframes, then cut down, rearranged and squeezed onto early home computer diskettes with impressive technical engineering. But few have played this original TRS-80 release, developed by Infocom but published in 1980 by Personal Software for sale through Radio Shack (an Apple II edition was marketed separately.)

Later, of course, Infocom became a publisher in its own right and renamed this original game Zork I, expanding on material left over from Dungeon to produce the famous Zork trilogy. Publisher Personal Software also produced Space Warp, an improved TRS-80 version of the unlicensed mainframe "Star Trek" games that also inspired Atari's Star Raiders.

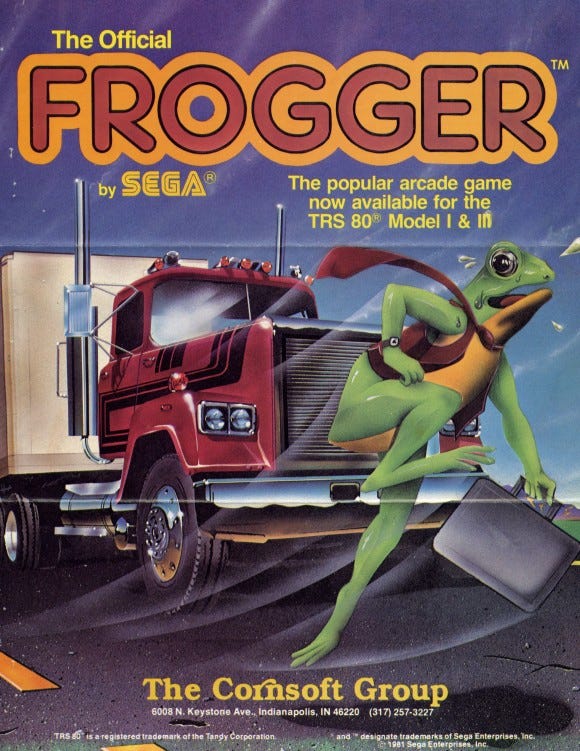

Frogger and Zaxxon (1981, 1983)

Early home computers hosted plenty of arcade action games "inspired by" the latest coin-op hits, without benefit of licensing (see below). This was mostly due to cost, paperwork considerations, and sheer naiveté-cum-chutzpah, but the small size of the market in dollar terms tended to keep the lawyers away.

This began to change when Sega took a more liberal approach with its licensing -- Atari was unable to tie up exclusive hits like Frogger and Zaxxon, and the TRS-80 was among several platforms hosting official, authorized ports (Frogger was created by Konami but controlled by Sega at the time.)

The Cornsoft Group's official TRS-80 version of Frogger was severely hampered by the system's 48-line vertical resolution, which forced the arcade game's vertical gameplay to be split across two screens -- after crossing the road on one screen, the display would flip to the river section. But the game did manage to render the game's familiar musical theme in three-part harmony, no mean feat on the TRS-80, and it certainly played enough like its namesake to merit the name.

Zaxxon, arriving late in the platform's life, is a truly impressive feat of TRS-80 programming -- the isometric display scrolls smoothly, it's not hard to see what's going on despite the blocky graphics, and all the gameplay elements are intact. The game was surprisingly well-suited to the TRS-80's display -- its fundamentally stair-stepped graphics made diagonal scrolling much smoother and less jarring than on other platforms. There are even parallax-scrolling stars in the background, lending visual depth to the action that the original Zaxxon arcade hardware couldn't match.

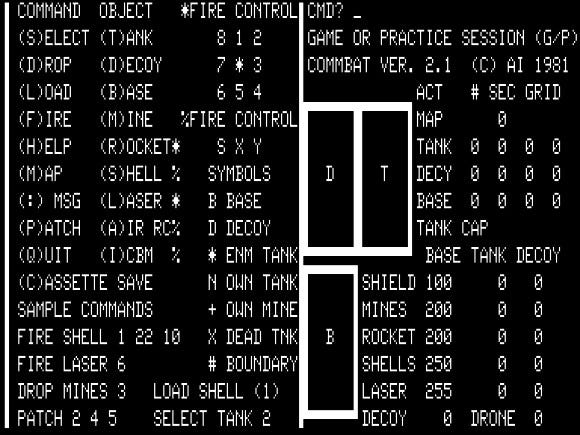

COMMBat (1981)

COMMBat was a very early online player-versus-player game for the TRS-80, so named because the system's COMM port was used to interface with the modem. The technology was extremely primitive by modern standards -- there was no lobby or server system, no way to find a stranger to battle. Arranging a match meant finding a friend with the same equipment and software, ideally within range of a cheap local phone call, and then setting up a time to connect to each other and play.

The game looks and feels like a mainframe exercise -- the command line-driven gameplay is methodical and slow, though its turn-based nature minimizes the painful lag one would otherwise expect at a 300 baud transfer rate.

There are no graphics to speak of, and the gameplay is essentially Battleship with tanks that can explore the playfield and fire at will. But in an era where computer AI was also in its infancy, allowing players to take on a fellow human being was a huge advance in terms of pure strategy gameplay. COMMBat didn't have to look good to inspire passionate battles.

Tunnels of Fahad (1980)

Tunnels of Fahad isn't particularly notable as a game -- it's an "interpretation" of Atari's 2600 classic Dodge 'Em that simply replaces the original's racing cars with an explorer and a mummy, accounting for a visible drop in speed while adding a bit of atmosphere. But it's technically solid, and it's also one of the first commercially published computer games written by a female programmer, one Kathy Pfeiffer, who at the time was apparently obliged to bill herself as the gender-disguising "K. Pfeiffer." This is also an early example of today's publisher/developer division of labor, as Ms. Pfeiffer wrote the game on behalf of Micro-Fantastic Programming, for publication by Adventure International.

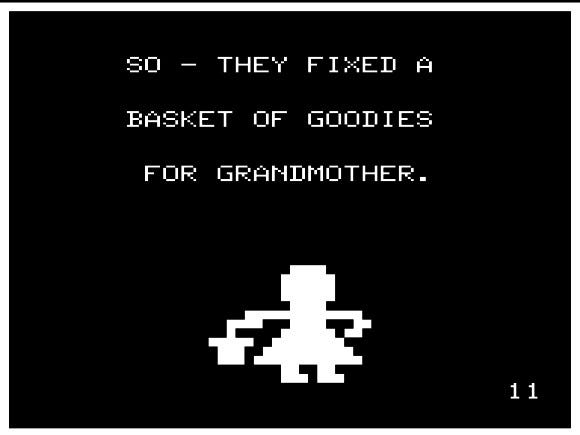

Kid-Venture #1 - Little Red Riding Hood (1980)

James Talley's Kid-Venture #1 - Little Red Riding Hood was an extremely early "multimedia" title, taking advantage of the low-end TRS-80's cassette storage system -- really just a consumer-grade Radio Shack tape recorder with an official TRS-80 logo on it.

The story mode presented the familiar tale of Little Red Riding Hood, with blocky graphics, text and simple computer-generated music. The visual presentation is augmented by read-along narration on audiotape, delivered with charming low-budget awkwardness by the programmer, James Talley. The audio is synchronized to the gameplay in simple book-and-record fashion -- we hit the space bar when the bell sounds.

The story is simple and remarkably conservative compared to modern children's entertainment -- the moral of the tale seems to be "do what your mother tells you" -- but it was an interesting technology experiment. One additional Kid-Venture was produced, but the sequel eschewed audio narration, perhaps because diskettes were growing in popularity, or because families hated rearranging the cassette recorder cables after loading the game in order to make the narration audible.

Death Dreadnaught (1980)

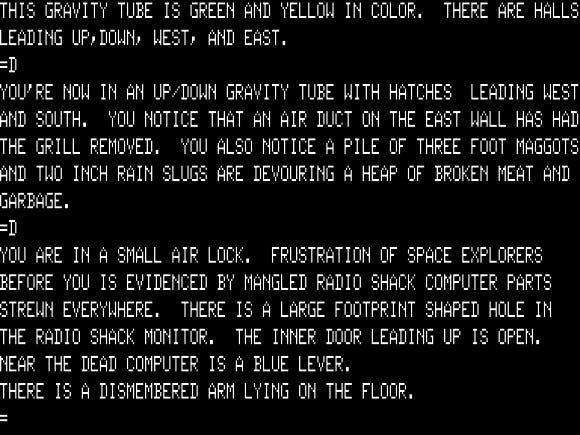

Death Dreadnaught's publisher, the Programmer's Guild, claims this was the first "rated" game -- computer magazines of the era were uncomfortable with proposed ads for this atmospheric and moderately gory text adventure set aboard an alien-ravaged starship. So the game sported a self-imposed "R rating", borrowing from the MPAA in a wholly unofficial manner, and thanks to the controversy, sales skyrocketed.

Buyers seeking something really nasty were likely disappointed -- there's very little actual violence in the game, though there's plenty of evidence of violence in the recent past. The TRS-80 itself even came in for a little pre-invasion abuse, as the deceased space explorers (and the authors billed only as the Mutt Brothers) have contributed frustration-mangled Radio Shack computer parts to the ship's pools of viscera and dismembered limbs.

The Wild and the Weird

The TRS-80 hosted a number of experimental games that didn't necessarily lead to greater things. It was the perfect platform for a lone programmer with a quirky idea, and some odd but interesting titles made it to market.

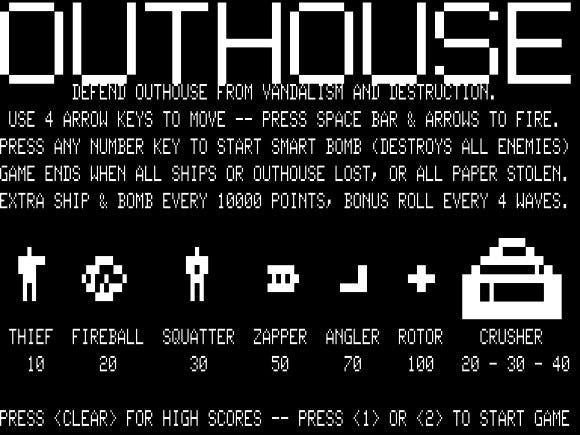

Outhouse (1982)

"The aliens are coming! And they're stealing our toilet paper!" That's pretty much the concept in this original arcade action game by John Weaver. The player's laser-equipped spaceship has to protect the local privy from alien creatures that fly through the sky, and, closer to home, zombie-like vandals who walk in from the sides of the screen, violate the sacred outhouse, and begin unspooling the precious TP as the remaining footage counts down.

It plays like any number of arcade shooters, with elements of Space Zap and Stratovox, but it's not exactly like anything else out there.

Dancing Demon (1979)

Leo Christopherson was one of the most talented animators working on the TRS-80, adapting to the system's limited graphics to create appealing characters with fluid movement and considerable personality.

Dancing Demon was not really a game, but a fun creativity tool -- users could enter music, note by note, and arrange choreography to go along with it, stringing together a series of canned dance steps to put a tap-dancing demon through his paces. A wacky and unique entry in the annals of early computer gaming, Dancing Demon stayed in active release for years, issued by three different publishers -- including a stint as an official Radio Shack release.

Paddle Pinball (1981)

What do you get when you combine pinball and Pong? Well, you get Eric Quintana's Paddle Pinball, a not-entirely-successful hybrid. The single-pixel rectangular ball behaves according to something like physics, with a certain amount of randomness built-in and a touch too much gravity.

The game's most notable feature is the playfield editor that preceded Bill Budge's Pinball Construction Set by a couple of years, allowing players to modify and save the layout to cassette. The feature is well-hidden and not likely to be found without reading the manual, and the editor also does nothing to prevent the player from creating board layouts that interfere with paddle movement or are prone to stuck balls. But it was an innovation at the time -- though it still feels odd playing pinball with a paddle.

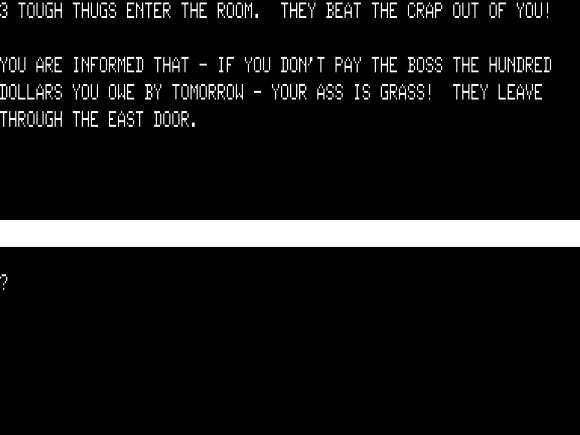

Misadventure #2: Wet T-Shirt Contest (1982)

There weren't a lot of "adult" games released during the TRS-80 era, but Softcore Software's series of text Misadventures, created by "Dirty" Bob Krotts, were a good deal saucier than Leisure Suit Larry could ever be.

This second game in the series was a fairly standard text adventure, but in addition to its uncensored use of mild profanity, it featured one pioneering mechanic: the player starts out as a male, but must switch genders to enter the title competition. Whether intentional or not, the end result allowed the player to feel exploited as a woman and guilty as a man, likely disappointing its target demographic but reinforcing the emotional power of simple, text-based interactive fiction.

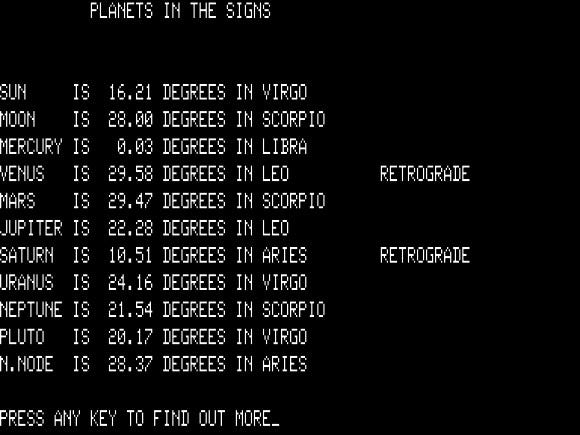

Astrology (1979)

I'm not quite sure where the 1970s astrology craze and the TRS-80 met, but their woebegone stepchild was Radio Shack's Astrology program. Given the user's birth date, time and location in latitude and longitude, the program would compute where all of the heavenly bodies were at that moment in history, as defined by the standards of this age-old art of codswallop. It might have been entertaining if it had been able to generate actual newspaper-style horoscopes, but 16K of cassette-based code wasn't about to pull that off; the TRS-80 struggled quite enough just doing the basic solar system calculations the exercise required.

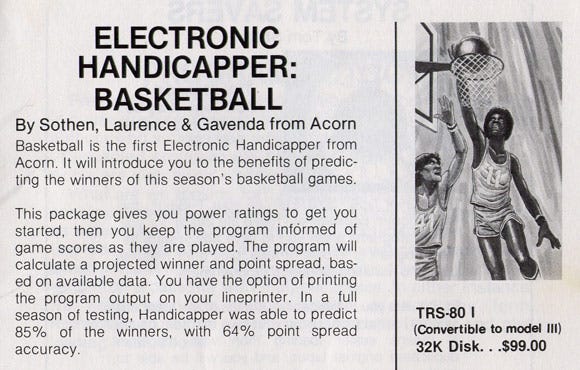

Electronic Handicapper: Basketball (1981)

What kind of entertainment software package retailed for $99.00 in 1981? Acorn Software's Electronic Handicapper: Basketball was not a game, really, but a slyly disguised business proposition. It promised a way to beat the odds with "sophisticated" computer analysis, and while this catalog advertisement doesn't explicitly mention anything as uncouth as sports betting in any way, shape or form, the selling price alone implies a certain you-scratch-my-back ethos.

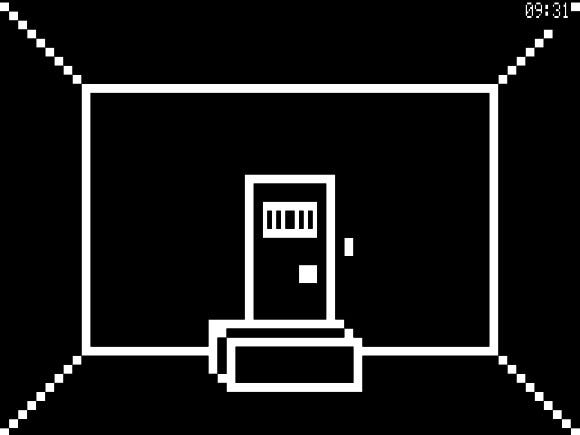

Asylum (1981)

The first person shooter as we know it was still a few generations off, but Med Systems' early first-person escape adventure Asylum managed to capture a little of that heart-in-throat feeling. While the TRS-80 couldn't handle animated 3D in real-time, the machine-language program runs quickly as the perspective shifts from one straight-on view to another, and never dampens the tension. Navigating an unfamiliar space, with no idea what might lie around the next corner, made for an engrossing experience despite the limited technology.

The Bootleg Arcade

Frogger and Zaxxon were the exceptions in these early years -- most TRS-80 "adaptations" of coin-op games casually ignored minor concerns like proper licensing. But when there was no official alternative -- that is, just about everywhere -- players made do with a number of recognizable, albeit illegitimate, ports.

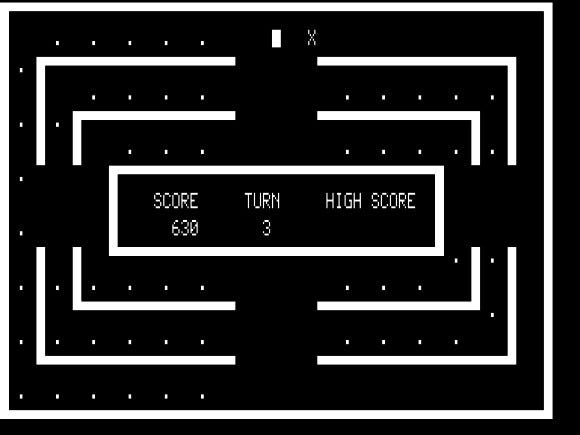

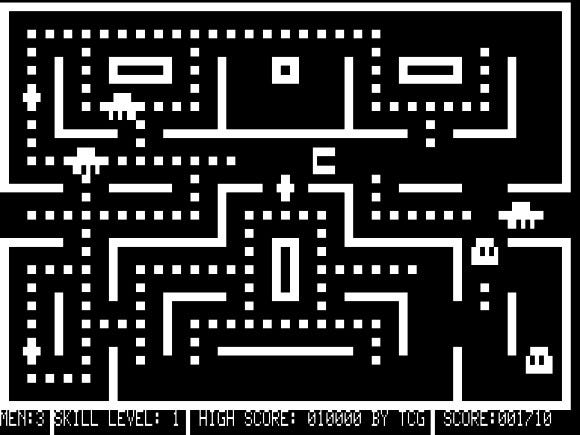

Scarfman

Before The Cornsoft Group went legit with its Frogger conversion, the company had its greatest success blatantly ripping off Namco and Midway's Pac-Man.

The player's avatar is reduced to a blocky C shape locked into position like a pipe wrench; the five (innovation!) ghosts can't turn blue, so they are forced to shamefacedly cast their eyes downward instead; and the game's chirp-chirp-chirp chomping sound effect is maddening. But it does play like Pac-Man, more or less, especially when using one of the aftermarket Atari joysticks.

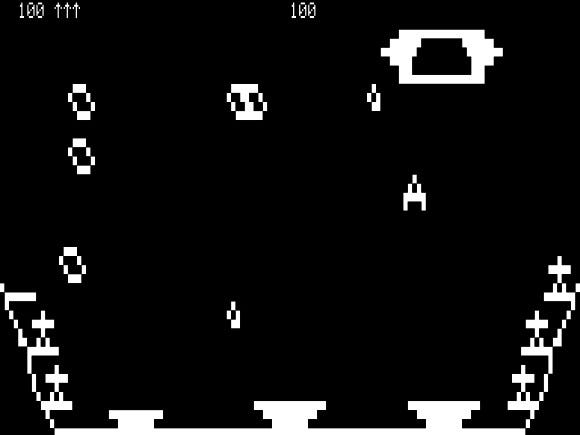

Meteor Mission II

"Inspired by" the early Taito classic Lunar Rescue, this Big Five Software effort remains a compelling gameplay experience. The player's tiny pod has to maneuver to the planet's surface through a scrolling asteroid field, rescue a stranded astronaut, then make its way back up to dock with the mother ship. Fuel is limited, and the pod can only fire its puny weapon upward, making the landing very different from the return trip.

Big Five also produced a solid version of Exidy's maze chase Targ, under the title Attack Force, with smart enemies and well-implemented acceleration and deceleration.

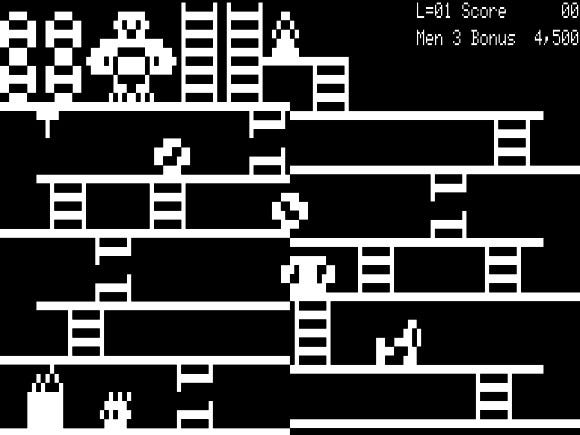

Donkey Kong

This one is a lost classic -- Wayne Westmoreland and Terry Gilman wanted to adapt Nintendo's hit to the TRS-80, and so they went ahead and did so. But Nintendo was unwilling to officially license the game, and so this title went unpublished, languishing in the authors' archives until long after the TRS-80 was commercially dead. While the visuals retain little of Shigeru Miyamoto's cartoon charm -- Mario has no hat or overalls, and his love interest resembles a fire hydrant -- the game is very playable, and just as faithful to the coin-op as the same team's Zaxxon. Like many TRS-80 games, it looks a lot better in motion, with movement helping to distinguish sprites from the background.

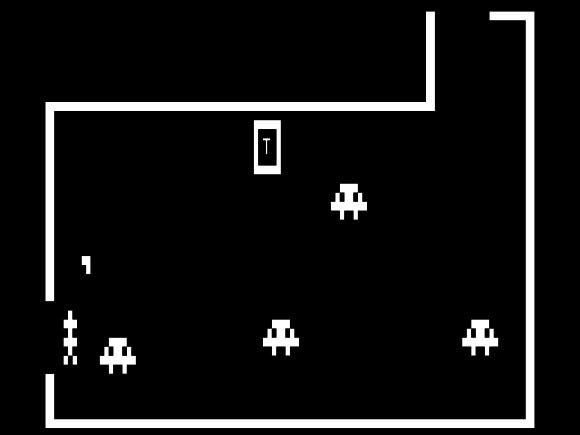

Venture (1982)

Why bother to even invent a sound-alike name, when you can just use the arcade game's title and cross your fingers in case the lawyers show up? Horizon Software's adaptation of Exidy's Venture is so difficult as to be almost unplayable -- for all the wrong reasons. The TRS-80's limited vertical resolution makes the main screen's maze difficult to navigate without getting trapped between encroaching spiders, and if our hero actually manages to enter a room in search of treasure, his shots crawl across the screen, taking one enemy creature out while the others close in to seal his fate.

Crazy Painter (1982)

The whole family could enjoy The Cornsoft Group's Jackson Pollock Simulator... no, wait, that's not right. Does anybody remember one of Williams Electronics' lesser-known coin-op games, Make Trax? Anyone? Well, the Cornsoft Group's Roger Pappas (Frogger) adapted it to the TRS-80 as Crazy Painter. Without the benefit of color and the arcade game's maze structure, the player's paintbrush, the enemies who threaten to destroy the paint job, and the very object of the game vanish into a morass of random pixels.

TRS-80 Roots: Publishers and Trends of Later Note

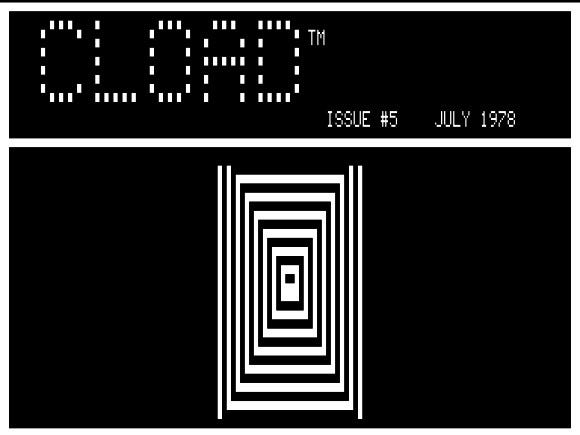

SoftSide Publications and CLOAD Magazine (1978)

As the fledgling home computer market struggled to find its audience, software was hard to come by and largely self-published. The market wasn't yet large enough to support software stores, and there was no internet to facilitate download of freeware or shareware.

But there was a hungry audience out there, so necessity led to innovation in the form of cassette (and later disk) magazines. CLOAD Magazine and SoftSide Publications both debuted in 1978, providing subscribers with ready-made utilities and simple games at a reasonable per-issue cost.

Most were written in easily-customizable BASIC, satisfying the early market's do-it-yourself ethos while providing a leg up for the novice computer users, and the modern downloadable indie game scene owes a certain debt to these pioneers.

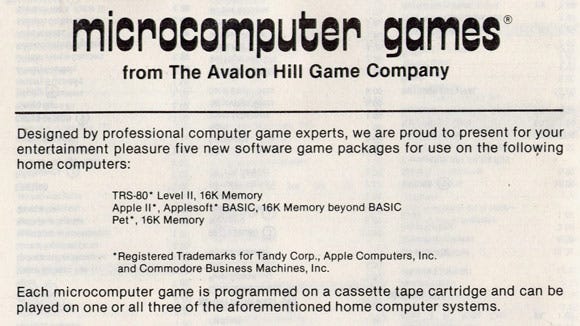

Avalon Hill Microcomputer Games (1980)

Wargame and pencil-and-paper RPG publisher Avalon Hill was among the first to venture into computer games in 1980, producing hex-map wargames and strategy titles for the TRS-80 and its contemporary platforms. These turn-based, graphically sparse games were a long way from X-Com or Civilization, but they provided a counterpoint to the "TV games" of the era and paved the way for more sophisticated gaming on PCs.

While the chief attraction was that these games could be played without the hours of setup and lengthy group commitments required by their tabletop forerunners, Avalon Hill also innovated with its multi-platform releases -- even though there was no common engine and games had to be coded specifically for each machine, multiple versions were released on the same cassette tape.

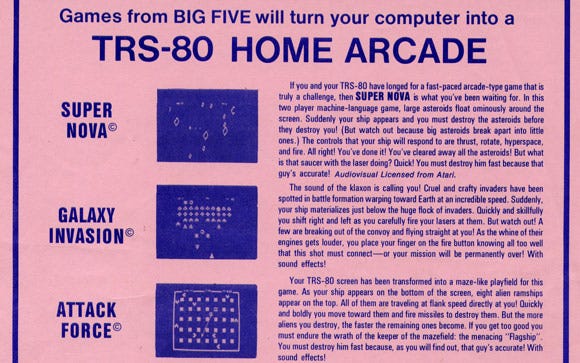

Big Five Software (1980)

Big Five's founders, Bill Hogue and Jeff Konyu, were bound and determined to make arcade games viable on the TRS-80. They borrowed heavily from the coin-op scene, with releases like Super Nova (an Asteroids clone) and Robot Attack (a copy of Stern's Berzerk, featuring another technical innovation with digitized voice samples), and they engineered the TRISSTICK, modifying standard Atari joysticks to work on the TRS-80.

The company is best known today for following its TRS-80 line with Bill Hogue's breakthrough hit, Miner 2049er, debuting on the Atari 400/800 and still around in cell phone form today. A TRS-80 version of Miner 2049er was advertised in the mid-1980s when the title went broadly multi-platform, but despite the nostalgic appeal, it was apparently never published or even developed.

Brøderbund (1980)

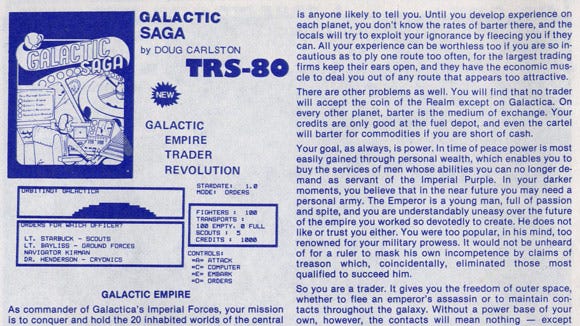

(Click for larger version)

Brøderbund became a major software publisher in later years, with game hits including the Carmen Sandiego series and a series of cartridges for the Nintendo Entertainment System. But founding brother Doug Carlston's elaborate Galactic Saga space strategy/trading trilogy was originally published by Adventure International, before the brothers Carlston started publishing on their own.

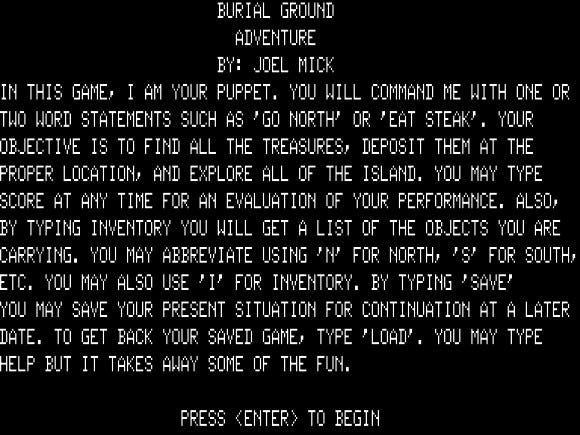

Joel Mick Text Adventures (1979)

13-year-old Joel Mick's story is not particularly unusual, but he's one of the few early TRS-80 game coders whose career can be traced over the longer term. He got his start in the game industry developing and marketing his own text adventures for fun, via mail order, at nominal cost. Although the first wave of computer gaming went bust in the mid-1980s, forcing many early game coders to seek more traditional IT employment, Mr. Mick stayed in the field of game design after college. He went on to design numerous games in more traditional formats, and was notably part of the original Magic: The Gathering team.

The End of the TRS-80 Era

Hardware cycles are a recognized and predictable challenge for the game industry today -- a successful platform has five or six years of solid success, an unsuccessful format a briefer existence. TRS-80 publishers catering to gamers were generally small and on the edge of solvency, and as the system aged, it became clear that most were tied too closely to Radio Shack's flagship machine. Activision and EA were young too, but they supported multiple newer platforms and managed to weather the storm.

Most TRS-80 publishers did not survive the era, and many blamed software piracy for the end of the ride -- modems and illicit BBSes had become popular, and by 1983, it was hardly worth advertising a new game for more than a month, as once it was released it would almost immediately become available through underground channels.

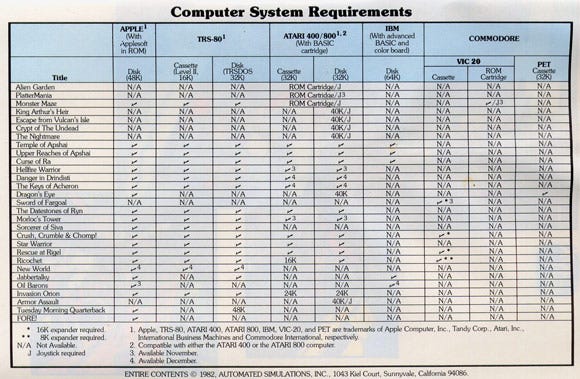

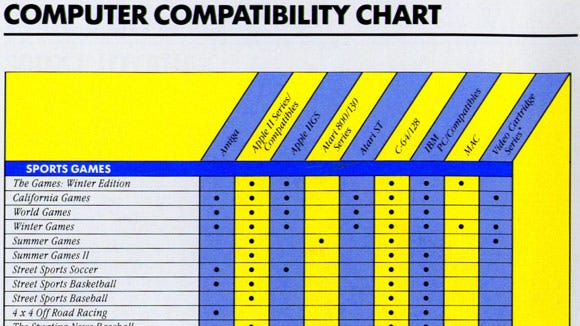

But the TRS-80 had other problems -- it was clearly more technically limited than its primary competitor, the Apple II, and software support for Tandy's little gray box dropped off as technical standards and gamers' expectations rose. In 1982, Epyx was still supporting the TRS-80 alongside the Apple II, which was just starting to pull ahead in the race for market share:

(Click for larger version)

But while this mid-1980s Epyx catalog still features a wide range of Apple II titles, the TRS-80, so popular a little bit earlier, is now nowhere to be seen:

(Click for larger version)

This was not a reversible trend -- while the TRS-80 Model III and IV computers cleaned up some of the original's aesthetics, the system's basic capabilities were clearly being outstripped by its new competitors, especially in the game arena. Concepts that just barely worked on the TRS-80 were becoming fully realized experiences on the newer 8-bit machines, and Radio Shack's aging machine became less and less able to compete. Gamers didn't suffer, but they did move on, and they did so more suddenly than an industry unaccustomed to platform shifts had anticipated.

The TRS-80 occupies a unique position in gaming history -- it enjoyed early success because it was early to the party, cheaper than its competition, and easy to find at the local Radio Shack. It bridged the gap between the hobbyist kit computing era and today's all-purpose consumer computer. And it dominated the home computer market just long enough to provide fertile ground for many early games, and concepts that still inform interactive entertainment today.

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like

.jpeg?width=700&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)