Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

After 23 years and 267 issues, IDG's GamePro magazine and website officially went offline December 5. Kevin Gifford, who worked at GamePro in the early 2000s, reflects on the media franchise's evolutions over the years.

December 6, 2011

Author: by Kevin Gifford

[After 23 years and 267 issues, IDG's GamePro magazine and website officially went offline December 5. Kevin Gifford, who worked at GamePro in the early 2000s, reflects on the media franchise that hardcore gamers loved to hate, but seem oddly sorry for now that it's gone.]

Why does anyone care about the demise of GamePro? Didn't we, the internet echo-chamber collective, just spend the past decade dismissing the magazine and website as lazy, airheaded fluff? Isn't this the magazine that invented ProTips culled from the instruction booklet and slapped more day-glo '90s color on every page than Wired?

This is the magazine that thought the fake personas the edit staff wrote under were so wickedly cool that it released action figures of the most popular ones? I'm not trying to dance on the mag's grave -- it's always a sad thing when talented people in the game industry get laid off -- but isn't GamePro's closure a sign that game media is finally starting to gain some sorely-needed maturity and respect?

Maybe not. The sad, wistful response to last week's news that publisher IDG would fold the brand into PC World and concentrate instead on custom game-oriented content for vendors came as a surprise to many on the net -- and quite a shock to a lot of ex-GamePro staff.

It was a shock to me, at least. GamePro was my first non-retail job ever; I worked there for almost two years in 2002 to 2003 before jumping ship to 1UP, and my chief memory of the experience was that the closest thing to praise we ever received was akin to "Nice mag, but why don't you have any codes for Halo?"

And yet you have pages upon pages of fond nostalgia sprouting around all over the place. Maybe anything that lasts 23 years in this industry can't help but attract some fans. Maybe the vast print and online redesign engineered by former Ziff Davis editorial director John Davison attracted more attention than I thought.

But maybe there really was something about that GamePro formula, something that the Electronic Gaming Monthlys and the GameFans and even the Game Informers of the world couldn't duplicate.

But maybe there really was something about that GamePro formula, something that the Electronic Gaming Monthlys and the GameFans and even the Game Informers of the world couldn't duplicate.

GamePro may not have had hardcore passion, but somehow it's made a profound mark on the industry -- and on thirtysomethings nationwide, judging by how often you hear people sarcastically offering ProTips in daily conversation.

Some magazines, like Dave Halverson's GameFan or the mid-'80s Newsfield titles that still define UK game media today, were born out of the sheer enthusiasm of the editors that created it. GamePro is not one of those magazines. It was unabashedly corporate, founded by the ex-CFO of unlicensed NES game publisher Tengen, hoping to capitalize on the explosive popularity of the Nintendo Entertainment System.

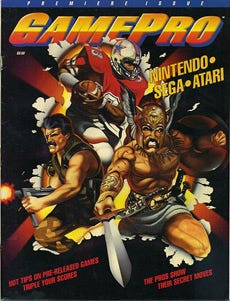

Patrick Ferrell's four-person team printed half a million copies of the first 60-page issue with their own money in 1989, shopping it around at the Consumer Electronics Show in hopes of attracting advertising.

"That was sort of a fake magazine," recalled Wes Nihei, who joined the edit staff with issue 2 and stuck around until 2004. "It was made to bring around to CES, this group of entrepreneurs going around the booths and saying 'Hey, we're GamePro, we got a magazine,' even though it wasn't really true."

The 500,000 issues wound up getting liquidated through Toys R Us in May of 1989. This had a dual effect: it attracted the attention of IDG, a massive computer-magazine publisher who purchased the title soon after, and it also netted GamePro the talents of Francis Mao, an artist who contributed to Eastman and Laird's black-and-white Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles comics in the '80s.

"I used to do spot art," Mao said last year, "just a couple short stories for Marvel and DC. Then I realized that I'd never make any money. So since I had Chinese parents, I went to college and got an English degree, which meant that I was going to be a lawyer."

"But I was failing out of law school because I hated it, so I played video games to pass the time. In May of 1989 I went to Toys R Us to get Contra for the NES, and that copy of GamePro came with it. There was an art contest where if you sent in art of your favorite villain, you could win $100, so I did this big painting and sent it in. Two weeks later I get a call from the creative director, and he said 'I love your art, but you didn't win the contest because it's meant for little kids.'"

GamePro's trademark look -- the bright colors, the extensive original artwork found in and around the features, the editor personas -- was mostly the work of Mao. That, combined with the unique airbrushed pieces from Mark Erickson that adorned most covers in GamePro's early years, made the mag look like nothing else on the shelves.

Game Players and VideoGames & Computer Entertainment looked stodgy by comparison; EGM was small-time and amateurish; and the all-dominating Nintendo Power, while great for its exhaustive strategy guides, was still in its infancy and written in a weird translated English that it didn't really shed until the N64 era.

The magazine's standard style was pretty well set in stone toward the end of 1990, by which time the Mao-drawn editor portraits and the smiley face-oriented game rating system were both firmly in place. The personas, in particular, stuck around all the way to 2008, even though they were only created in order to disguise the fact that GamePro had a tiny staff when it launched.

"Within the first year that I was at GamePro," former senior editor Dan Amrich reflects, "I said, 'Do we really need these cartoon characters?' I was proud of the reputation I was building and I wanted to keep writing under my own name. But everybody said 'We all asked the same thing, and we've never gotten anywhere.' I thought they were silly and would get in the way of credibility, but it became clear that they were part of the GamePro brand, and the management had a very strong 'if it ain't broke, don't fix it' vibe -- to a fault, because even when we did feel things were broken and needed fixing, we couldn't make positive change."

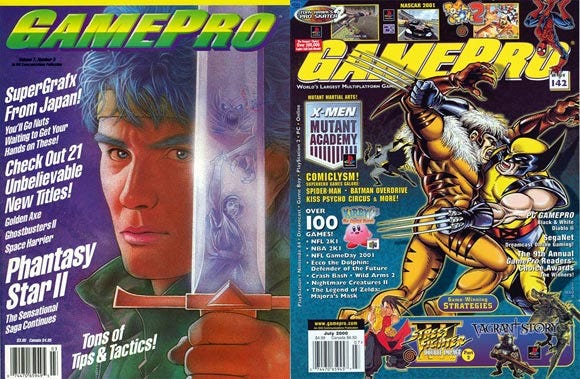

This struggle between GamePro's editors and IDG's management was plain to anyone working there in the early '00s, when I showed up. Years of tradition had led to a rigid, if largely unwritten, set of rules for writing and designing the magazine. Covers would often take the kitchen-sink approach, throwing tons of characters under the GamePro logo -- to the point where every magazine looked like a wrestling match.

Writers were forbidden from using the first-person pronoun in any article, the idea being that everything in the magazine was the unified opinion of "The GamePros." There was one lunch meeting I recall pretty vividly where we discussed the word "I" and its wondrous merits to the boss for an hour and a half, to no particular effect. GamePro.com, the website that originally launched as an America Online-exclusive "channel" in 1995, offered a lot more freedom, but (despite many redesigns and some well-received features, like Kat Bailey's Roleplayers' Realm podcast) it never attracted a critical mass of readers, always remaining firmly behind the first tier of game sites.

Even with a circulation that kissed a million in the late '90s and was still nearly 500,000 copies in 2004, GamePro seemed to be rudderless through most of its last decade of life. The publisher purchased Star Wars Insider magazine in 2004 in order to expand its entertainment portfolio, only to sell it again after 14 issues. That same year, IDG launched GameStar in the US, a multiplatform mag that aimed for a more "mature" audience by putting blonde models on the cover and Maxim-y lifestyle articles inside; that limped through three issues before closing, though it remains alive in Germany.

It took the circulation to drop below a tenth of its high point before IDG finally took action. Management acted boldly, hiring former Ziff Davis editorial director John Davison and essentially handing him the keys to the Ferrari.

"When I began talking to them, it was unlike any discussion I'd ever had with any other media brand," he recalls. "My last conversation before signing on the dotted line was with IDG president Bob Carrigan. Given that the brand had recently passed its 20th anniversary, I asked him what the company felt GamePro really stood for, and what I should try and build around. I was expecting an infuriating list of company mandates that would make effecting any kind of change really difficult, but instead he said 'That's why we're talking to you -- things need to change; you tell us what that should be.' That kind of freedom is really rare for someone in my position, so I pounced on it."

The new GamePro of 2010, while maybe a third as thick as the monster issues of the mid-'90s, was a massive improvement. Gone were ProTips, strategy content, and cartoon editors; in its place were massively in-depth features, interviews, and reviews that concentrated on writing quality over covering all the PR lines.

"I spent a lot of time talking to readers, to the staff, and to people in the industry," Davison said, "and the feedback on the brand's image was pretty much the same across the board -- that it was a great brand from 20 years ago, but which had lost any real sense of identity in recent years. It needed a reason for being, so that's what we set about trying to give it."

"We quickly realized that our best chance was to try and appeal to folks that remember it when they were younger, but who had grown up and now wanted something more mature and in-depth. We didn't really stand a chance of appealing to a younger audience, so we put our energy into focusing on people that felt the nostalgia, loved games, and were old enough to still hold a candle for print."

The problem with that was, as is plain to see given that you're reading this on a website, the audience has not only graduated from old-style GamePro -- they've graduated from print media, period.

"The old model of putting print product out into the market and hoping people will buy it is totally screwed," declared Davison. "The gaming audience is impatient, and it's used to getting information around the clock for free. If you want them to both wait and pay for something, it has to be pretty special -- and it has to be totally justified."

Recently, under the leadership of its last editor in chief, Julian Rignall, the magazine switched to a quarterly publishing schedule, but this did no good -- the staff only managed to ship one issue before it closed.

Rignall told Gamasutra this August that the change was made to make the magazine "economically viable" -- a comment that obviously did not bear out. "I get the fact that there are a lot of people who don't want to read magazines anymore, but there are people that do," he said, at the time.

In the end, it was a situation that IDG could no longer make money off of. Thus GamePro is dead. It wasn't for lack of talent. Perhaps more than any other NES-era mag's staff, most GP alumni are still in the creative side of the biz, landing in companies from Sony and Capcom to Activision and Blizzard. It wasn't for lack of devotion to the brand, either, as this past week's online outpouring of emotion for the magazine has shown.

Instead, it's the latest signpost along the very long, winding road that game media's been forced to take since the turn of the millennium -- transforming itself from that classic authoritarian "We are the GamePros" stance to one where the users -- the people posting on forums and shooting YouTube rants about whatever pissed them off on Xbox Live last night -- have become far more important than any paid staffer could ever be.

The GamePro staff in 2003 (Kevin Gifford, author of this article, fifth from left)

To Dan Amrich, who (as head of social media for Activision) works in all the forms of online communication that are hammering the final few bolts into print media's coffin right now, it's a necessary, if bittersweet, transition to make.

"I invested a lot of myself while I was there," he wrote. "It was not my first job, but it was a place that I really felt I belonged. I worked on the website way back in 1997. I worked on the print mag. I wrote news and reviews and previews and cover stories. I created two meta-puzzles, huge hidden contests in two issues. I worked like crazy and loved it. I won Employee of the Year. I have a leather jacket with the GamePro logo on it to prove it. I still stay in contact with many of my coworkers from that time. It was a family."

It's a sentiment that, even though I was writing as an anthropomorphic fox in warlock robes who spoke Japanese, I can't find myself disagreeing with.

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like