Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

An examination of the introduction of Kwedit, a kid-centric service to allow gamers to promise to pay for virtual items and then deliver on it later may be the start of an important way to boost free-to-play revenues... or a mere blip.

Gamers of a certain age may recall the catchphrase of Popeye's pal Wimpy: "I would gladly pay you Tuesday for a hamburger today." Borrowing money for something so trivial seems a bit silly -- but as of this year, virtual items can be bought on credit thanks to a Mountain View, CA-based upstart called Kwedit Inc. whose catchphrase is "Play now, pay later."

But in an age of easy credit and a troubled economy, some observers wonder whether extending credit -- or "kwedit" -- to gamers as young as 13 is appropriate.

Launched just last month, Kwedit's goal is to solve what it says is the number one problem for publishers in the free-to-play space - the fact that the vast majority of gamers, perhaps 98 percent of them, never spend a penny on the virtual items offered to them.

"One of the reasons why the typical conversion rate is 2 percent or lower," says Danny Shader, Kwedit's CEO, "isn't because the gamers don't have the resources or aren't willing to pay. There is a group of people who just lack the mechanism to do so.

"Picture someone with a $10 bill who wants to shove it into their screen but can't. They are the 'unbanked', or those who prefer to pay with cash. Or perhaps they just didn't think to buy a pre-paid card earlier in the day or they are unwilling to purchase one by phone.

"And so we needed to come up with a way to let those people who have the will and the resources make a payment. We only have to do that for a very small percentage of the 98 percent who aren't paying to generate a huge increase in the amount of revenue a publisher can earn."

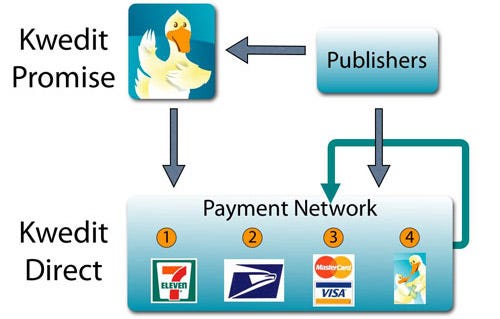

Here's how Kwedit works: On websites that accept Kwedit Promises, gamers get to buy virtual items now by promising to pay up in a week or two. At that time, they can hand over cash at a store, like 7-Eleven, that takes Kwedit payments or they can "snail mail" cash in a pre-paid Kwedit envelope that can be printed right off the web.

The amount they can "promise" in the future grows -- as previous promises are paid up. This increases their Kwedit score, a virtual version of a FICO credit score. The initial Kwedit limit is determined by the game publisher and might typically be just a few dollars.

The amount they can "promise" in the future grows -- as previous promises are paid up. This increases their Kwedit score, a virtual version of a FICO credit score. The initial Kwedit limit is determined by the game publisher and might typically be just a few dollars.

Unlike using a "real world" credit card, there are no serious repercussions if a gamer reneges on their promise other than the fact that their Kwedit score falls -- which may adversely impact their ability to use the system in the future.

"It's a completely virtual simulation of credit," says Shader, "in a completely safe environment."

But observers anticipate parents feeling uncomfortable with their children making promises when perhaps they are unable or unwilling to pay.

Shader minimizes the problem, observing that while Kwedit accounts are for gamers 13 and older, "the largest demographic of people who play free-to-play games are 18 to 34-year olds. Why would these people use Kwedit? Not only do 25 percent of American households not have a credit or debit card, but a non-trivial number of people who do have credit cards are unwilling to use them online due to concerns of privacy, security, or just for budgetary reasons."

In addition, says Shader, Kwedit gives parents an "incredible teaching moment" to talk to their teenagers about credit, what it means, and what will "ultimately be the most important financial skill they will have to develop when they get older. That's why we're putting a tremendous amount of material on our web site explaining what this is all about."

Because Kwedit is so new, it's impossible to predict whether it will appeal to enough publishers to make it a success; to date, only two have signed on -- FooMojo for its FooPets and Three Rings Design for its Puzzle Pirates. All the others that Kwedit has approached, recalls Shader, are either taking a wait-and-see attitude... "or are so cynical they don't believe anyone will pay up on their promises."

Daniel James, CEO of Three Rings Design, is more optimistic, calling Kwedit's proposition "an interesting one," and he looks forward to Kwedit becoming a solution to the conversion problem that plagues him -- and all the other free-to-play publishers.

"I'll tell you very honestly that our average conversion rate for someone turning into a paying customer is about 5 percent," he explains. "So we've got a large population of players who are enthusiastically enjoying our game who have not transacted with us which is, of course, part of the free-to-play business model.

"Those people contribute to the game, we want them around, they are part of the community, but if there were a way of getting them to become customers, that would be worthwhile. And so we've signed up with Kwedit."

James confesses that initially he was reluctant to do so until he "got his head around the concept."

Says James, "People ask me, how am I going to be sure that gamers who promise to pay me, pay me? Well, the key thing with Kwedit is you aren't sure. Although you hope they'll pay you, you basically have to assume they won't. This isn't credit, it's Kwedit.

"There's no enforcement. No one is going to show up at your house and say, 'Hey, give us the money, kid!' But since they weren't going to spend money with you anyway, the risk is minimal. On the other hand, if they do pay, the upside could be very large."

If James is able to move his conversion rate from 5 percent to, say, 7.5 percent, he says, that would make a huge material difference to his business. "It is worth taking a risk in order to see if we can do that," he adds.

What enables him to shrug off non-payments, of course, is that the cost of creating the virtual goods that he sells is essentially zero. "We are like the Fed," he explains. "When they need more money, they print it. We do the same."

One risk for publishers is that gamers who might have legitimately bought virtual items with a credit card may now see the advantage of promising to pay instead -- and then reneging.

"That is a key question mark," says James, "and it's one that we will definitely keep an eye on although I like to think that the number of people who would do such a thing is exceedingly small."

Meanwhile, James has no results to report given the fact that Three Rings just began participating in the fledgling Kwedit program.

"People are making Kwedit Promises but I don't have data yet on how many or how quickly they're paying up or even whether they are keeping their promises," reports James. "It's too new. We are basically testing it with a significant number of players to see how they behave and, if the results are good, perhaps we'll roll it out more widely in a few months to some of our other games as well."

Kwedit's Shader looks forward to more publishers joining the system with additional games. With increased participation, the Kwedit score becomes more significant; a gamer whose score dips because they didn't repay a promise on one game will find themselves unable to get additional credit on any of the games in the system. Therefore, the more publishers adopt the program, the more weight a Kwedit Promise will carry.

At the same time, publishers have other payment options in addition to Kwedit Promises, currently the most popular being the pre-paid game card. In existence for four years now, it has proven itself to be a good alternative to credit cards. Three Rings utilizes such a card -- as does Nexon America, widely considered to be one of the concept's innovators with its Nexon Game Card.

"The pre-paid game card fits very well with our audience, most of whom are teens and college students, who don't own credit cards," explains Min Kim, VP at Nexon America.

Their card, which can be used for such games as MapleStory, Mabinogi, and Combat Arms, is currently sold at 40,000 locations nationwide of such retailers as 7-Eleven, Toys 'R' Us, Blockbuster, CVS Pharmacy, Rite Aid, and Duane Reed.

But what Nexon America hasn't built, Kim admits, is "the functionality to extend credit, which is the biggest weakness of the pre-paid card.

"If a gamer gets the urge to play one of our games in the middle of the night but they don't have a pre-paid card and they can't go out to the store to buy one, there's no way for them to spend anything with us -- even if we know they're good for it because they have a really stellar purchasing history and shell out $25 or $50 a month with us."

For that reason, Nexon America says it has been evaluating for over six months now the idea of extending credit based on a credit score -- a plan that sounds a lot like what Kwedit is doing.

"These are just ideas that are going back and forth inside the office and haven't seen functionality," says Kim, "mainly because we've been evaluating a couple of different initiatives, and everything seems to be a priority these days."

Despite the fact that Kwedit has beaten Nexon America to the "credit punch," Kim recalls that his reaction to the Kwedit Promise program was that he "thought it was pretty cool mainly because it allows publishers to create impulse buys while people are online, so it should work for a lot of companies, especially those without game cards. I mean, if you look at the retail space for pre-paid cards, there's not a lot of room for everyone.

"But because we have such a great relationship already with all the retailers who carry our pre-paid cards, I'm not so sure there's as much value for us," he adds. "If we adopt a credit program, it will be for people who want to transact when they can't, just to tide them over until they can get to the store the next day to buy a game card."

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like