Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

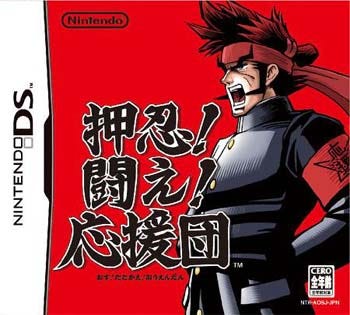

In this in-depth interview, iNiS co-founder Keiichi Yano (Elite Beat Agents) sat down with Gamasutra to talk about his work with Nintendo, the sudden rise of the rhythm game genre, and most vitally, how Japanese and American developers and technologies interact.

Microsoft's Gamefest event, held in August in Seattle, attracted large numbers of developers to come and learn more about Xbox 360 and Games for Windows. The vast majority, of course, were U.S.-based developers -- but a few foreign faces did show up.

One of those was Keiichi Yano, CCO, designer and co-founder of iNiS, creators of the iconic, Nintendo-published music game Elite Beat Agents for the Nintendo DS - and he shared his thoughts on the sudden popularity of the rhythm genre, issues in internationalizing game appeal, and the best places to get advice on development technique, among other topics.

So, the obvious question is, why are you at Gamefest?

Keiichi Yano: That's probably the biggest question I can't answer, but I guess there is an obvious answer, and a not-so-obvious answer. We've always been Xbox developers. A lot of people don't know this, but we've been doing graphics engines and game engines on 360 for awhile now.

You're talking about your rendering engine, nFactor2?

KY: Right, right. And we've been extending that all the time. It's cross-platform right now. It's just really continuing on that vector -- that was really the main reason I was here.

Could you go a little into what nFactor2 is about?

KY: Yeah, it's basically our rendering engine and our game development platform. It encompasses the main rendering engine, and the tools surrounding it. It's really our basis for creating all the games that we build.

You spoke to Gamasutra's Simon Carless before Tokyo Game Show last year. There was an allusion to a 360 project. Is that something that's still in the works and something you're still looking at?

KY: Yeah. We are currently working on a title. I can't really get into it more than, "Yes, we're working on something!"

Elite Beat Agents and its Japan-only predecessor Ouendan have a casual appeal -- they're easy to play. The casual market is a big deal right now. Is that where you guys want to focus, or are you doing a variety of different titles?

Elite Beat Agents and its Japan-only predecessor Ouendan have a casual appeal -- they're easy to play. The casual market is a big deal right now. Is that where you guys want to focus, or are you doing a variety of different titles?

KY: Since we're in the music games genre, music games lend themselves to a more casual market. The fact that we're doing that -- yeah, we're primarily already in that market, and a couple of things we're working on right now are definitely geared towards that market. I would say that in a nutshell -- yes.

Reggie Fils-Aime made a comment saying that Elite Beat Agents didn't perform as well as he'd personally hoped. But at the same time, if you look at the success of Guitar Hero, obviously music games have real mainstream potential. What do you think about the growth of the genre in the U.S.?

KY: I think with regards to the U.S. -- as well as Europe, actually -- music games will probably continue to be very big and will probably outgrow their current market status right now. Everybody's really looking forward to titles like Rock Band, and SingStar for PlayStation 3, and there are other titles in the works I'm sure that are probably fairly massive compared to what's been available for music games up until now. So yeah, I definitely think so.

But one of the things I would say to that, is that I'm very concerned about the quality of the music games that are coming out and will come out, because again, I do feel as though it's kind of a special genre that requires specific knowledge of music and what makes music fun. Hopefully, the games that come out that are in that genre can take advantage of all that and do all those things right, and make sure that it's a really fun experience so that the genre itself can stay strong and not have a lot of bad clutter in it.

Do you find that in the wake of the popularity of Guitar Hero, you're having to fend off more offers to develop games?

KY: Definitely, yes. We've been very lucky that a lot of publishers have really looked at us to do titles for them. We haven't unfortunately been able to cater to all the requests, but definitely it's been very good, and hopefully it'll lead to bigger and better things in the future, for everybody.

Is it easier for you guys to work with U.S.-based publishers, since you speak English with a native fluency?

KY: Definitely it's one of the things that I'm really pushing for. To answer your question, it's definitely easier to do, not to mention that it's something that I would want to do personally, and will probably do sometime in the future very soon. Yeah, it's all a good thing.

There's another element to this -- and Gamefest ties into this -- where the development houses in Japan are very closed in. Companies don't share tech, don't use a lot of middleware, and they do a lot of custom stuff for a title. Do you think iNiS is more able to take advantage of the Gamefest-style environment and this information because you can personally come here and participate? And also, do you think that this mentality is spreading in Japan during the next generation?

KY: Well, I definitely think that we have an advantage, especially for me. I'm kind of used to this. It's more alien to me sometimes when we can't talk about stuff, like in Japan. At the same time, I think that Japanese developers are starting to feel the pressure, and there is definitely a need for quicker speed, in terms of getting an idea and getting games up, and getting them up at a certain quality level right now. So yeah, I think that more and more developers will be looking to middleware. I don't know if you know, but the Unreal Engine is starting to get licensed to a lot of developers in Japan.

There are some real high-profile Unreal Engine games -- The Last Remnant from Square Enix, and of course Microsoft's Lost Odyssey. There are some more, but those are probably the highest-profile.

KY: Definitely. And as you know, the RPG genre is very big in Japan, so it's very important to have RPG developers on that middleware bandwagon. It'll definitely help those companies.

Microsoft's Unreal Engine powered Xbox 360 exclusive, Lost Odyssey

Xbox Live Arcade is also a very hot topic here, and in general the download services are taking off. What do you think about that market?

KY: Well, first of all, from a development standpoint, I really love it, just to be able to say, "Oh, I have this cool idea. I couldn't sell it for a retail box, but it might be really cool for a five-dollar download." So you can get a lot of interesting and neat ideas that otherwise wouldn't be realized. At the same time, I'm looking at the performance figures, and there is definitely a cap to what you can do. As long as you can work within those confines, I think it's a really great platform that'll continue to grow, definitely.

Do you think it's sort of a problem that the download services for the three consoles all kind of have their own quirks? Does that limit them?

KY: From my perspective, it's cool if we could create one game and share it across platforms and download services, that's one thing. I think that'll be the future, definitely. But at the same time, for us especially, we build games that really take advantage of the hardware that we're targeting, whether it be PlayStation or the DS or Wii. So it doesn't really make sense for us to want cross-platform capability there, because we always just tune to the hardware, not just in performance, but in the IO -- the input and the output, definitely, I think, is very custom, clearly. It doesn't match for us, but I can see where that would become very important in the future. You'd probably want to do more of that, going out.

Another thing that's interesting about your development is that Ouendan came out in Japan, and it didn't perform particularly well, let's be honest. But it got a lot of notice from the tastemakers in America, because it had a lot of interesting qualities. Thanks to that, it evolved into Elite Beat Agents, and then that sort of evolved back into Ouendan 2. It raised its profile across sequels. That's a unique scenario, in which there's one series that's got multiple entries that are territory-specific and it keeps going a little bit better as the process evolves.

KY: Well, when we first created Ouendan, we wanted to do something different with the music genre that people can relate to maybe a little bit more. When we first got the idea, I didn't even think about releasing the game in the States, obviously. And you're right -- the first batch didn't do that great. But the same thing I guess happened in Japan. A lot of the opinion leaders picked it up and spread the word for us.

Obviously, that can only go so far, but as we started doing Elite Beat Agents and Ouendan 2, it was interesting. We sat down with Nintendo and knew that we had to create another universe for [Elite Beat Agents], otherwise we have no chance. But yeah, we did that, and that was just the natural progression of wanting to bring the series and that game system over here. There's not really anything more to say than that.

What's interesting is that a lot of things that we did for Elite Beat Agents and a lot of things that we put into the thinking behind Elite Beat Agents really trickled down into Ouendan 2, in terms of minor things like the gameplay and whatnot. But at the same time, a lot of things that people don't consciously realize, but a lot of things we made conscious decisions about to make the game more accessible, really came down, and came down well.

What's interesting is that a lot of things that we did for Elite Beat Agents and a lot of things that we put into the thinking behind Elite Beat Agents really trickled down into Ouendan 2, in terms of minor things like the gameplay and whatnot. But at the same time, a lot of things that people don't consciously realize, but a lot of things we made conscious decisions about to make the game more accessible, really came down, and came down well.

Ouendan 2 for us did very well, and it continues to do very well right now. To that extent, yeah, even Nintendo told us, "Look, this is not a scenario that easily happens." What was really great for us was that the fact that Ouendan 2 is doing really well now, kind of drove Ouendan 1 sales now. So if you go to game shops in Japan, usually you'll see Ouendan 1 right next to Ouendan 2. We got a pretty sizable amount of sales after Ouendan 2 released, of Ouendan 1. I know they're making more copies right now and everything.

When I bought Ouendan 1, it was back when it was like super-underground, and I bought it for 2,000 yen [about $17] on the clearance rack. That was a couple of years ago, but now it's back.

KY: It's actually at retail price now, and it's easier to find now because a lot of retailers have gotten more.

That's not really a typical release pattern, in the sense that games do not usually come back into print.

KY: Yeah. We almost gave up! Again, I can say that we're very lucky that Nintendo made the decision to let us do the sequel despite the fact that sales were not that great. But I think they realized that having a fanbase like this doesn't come around every day. You get these things that people like and sell well, but to have a solid fanbase is a great thing, and I really thank the fans for that and for supporting us.

I went to a couple of community panels here, and it's come up a lot in terms of, for example, Forza 2's integrated community functions. The developers say that they feel community really drives continued interest in the title, and it drove interest for people to buy it who wouldn't have bought it. Is that something you're thinking about more directly integrating into future titles?

KY: Oh, definitely, definitely. I think the community aspect is something that you can't ignore now. It's something that'll be very important going out, and I think that games will be less boxed objects more than they are services. I tend to think of the projects that we'll be working on here on out more as services more than boxed games. It's definitely very, very important.

Elite Beat Agents was for Europe and North America, and the Ouendan series is for Japan. They're the same game, essentially, but with very different graphics and song choices. There are very few games that perform globally. You look at what Capcom's doing right now -- Devil May Cry is a global title, but Lost Planet is very obviously a Western-targeted title, even though it's developed in Japan. This also goes with Western developers wanting to sell their games in Japan: do you think that people are going to have to radically change a game's face to appeal globally?

KY: Well, I think it really depends on the game. I think the more that you take time to build a very detailed universe, you think -- there might be some things that you need to do. On the same token, you have to think that... for example, movies. Western movies come to Japan all the time. They're major hits, and all they do is subtitle them. I think going out, as we get away from the deficiencies of the boxes that we're confined to, and we go to more mainstream ways of telling our stories, I think that'll be less and less of a problem. Just going back to the community thing -- that'll be something that I think will start being very universal. Like with our titles -- a lot of people wanted to play the Japanese songs. On the same token, Elite Beat Agents actually did pretty well in Japan, because they sell Elite Beat Agents in some mainstream stores.

Yeah, I've seen it in [hardcore-beloved Tokyo district] Akihabara.

KY: Like in Sofmap.

They have it at Sofmap? [Note: Sofmap is a large electronics chain, akin to Best Buy in the U.S.]

KY: They have it in Sofmap all over Japan. If you go to Sofmap, you can buy EBA no problem. There's definitely a market for that. But once you have a community aspect in your game, it starts to become international, by the fact that you're already networked, and for us, once we're networked, a lot of the restrictions that we would have had are really kind of blown away. For example, we wouldn't be restricted on song selection, or even the country of the songs that they originated from. It's just a lot of things that we can take out.

I think with Ouendan, many of the songs weren't suited to the American mass market, but on the other hand, you had the opening theme song from Fullmetal Alchemist, which is on TV here. They broadcast it with the same Japanese L'Arc-en-Ciel song in the U.S., and it developed an actual fanbase that probably crosses over well with the game's fans. So it's like these decisions get murkier.

I think with Ouendan, many of the songs weren't suited to the American mass market, but on the other hand, you had the opening theme song from Fullmetal Alchemist, which is on TV here. They broadcast it with the same Japanese L'Arc-en-Ciel song in the U.S., and it developed an actual fanbase that probably crosses over well with the game's fans. So it's like these decisions get murkier.

KY: They do, they do. Well, what is the network all about? It's all about choice, right? It's all about trying to cater to very specific needs in a more powerful way. So that's why I keep referring to the fact that our games have to become more service-oriented in the end, because we're telling our stories, but at the same time, we are confined to a box, and we expect the user to play our performance from these boxes. We have to give them some type of an outlet.

If you go to a movie theater, the theater is your outlet. You have a lot of people there, and you already know that you're a part of a community -- the community that's watching that movie. With games, it's a lot harder to do that, unless you're doing some outside committees or groups or whatever to talk about their experiences with the games. I think more and more the integration above that will really help the internationalization of titles that we do, and it just happens to help a lot of things, and a lot of problems and stuff. Actually, for me, personally, as a developer, I think going out in the future, we'll have less problems, because we can take advantage.

At GDC, there is an increasing number of Japanese developers speaking, and Japanese attendees. Do you feel like things are globalizing more for the Japanese community? Is it just a reaction to the downturn in the Japanese domestic market?

KY: That's a very difficult question. I don't really know the answer to that. My feelings, first of all, are that we realize in Japan that a lot of the technology that we build our games off of originated either from the United States or Europe. There are very few things that are really created from scratch in terms of technology in Japan. So, in order to create a viable next-gen title, there are some things you can't ignore. I think definitely there is a reaction to that.

There needs to be more insight from a technical vantage, and just more of a game design sampling, I think. I know that Western developers are interested in Japanese thinking in terms of game design, so that's why I think a lot of game designers are called to GDC this year, including myself. I think it's really several things, but those two are probably the major reasons, I think. Hopefully, that'll continue to grow and Japanese developers come to the States or Europe more to gain information that we wouldn't be able to gain just being in Japan.

We did an interview with Ray Nakazato. He works for FeelPlus. They're doing Lost Odyssey. He said that the one problem they're struggling with is that much good info from the Unreal Engine is discussed by the users on the Unreal Engine forums and mailing list.

KY: In English.

By developers, in English. What does that mean, for you as a developer? Not that you're using Unreal Engine necessarily, but you've got to stay abreast of technology. What does that mean for you guys?

KY: Well, I think that you can't expect all of the information to come out from the source. The great thing about coming to the U.S. is that developers talk to each other. There's a lot of good parallel information exchange that can happen over here that usually doesn't happen at all in Japan. The developers, again, as you know, are very closed there. So yeah, this willingness to share information amongst developers, and I think just a lack of fear -- because a lot of times, people don't want to ask the wrong question in Japan, you know? But over here, it doesn't matter. You might ask the wrong question, but you might not, so people keep asking, and it'll get answered.

I think if anything, that requires support. [Speaking to other developers is] really the main venue for getting a lot of information, because a lot of times, the source doesn't understand what [it is that] you don't know. So unless you ask those questions, they go, "Oh, is that what you don't understand?" I think that's one of the key reasons why tools in general tend to be able to grow in the United States, where in Japan, tools don't really have the way to make it, because there's a lack of support and a lack of developers going in and saying, "Hey, I don't understand this," or whatever. It's getting the developers of that software to think about what they need to do to better support their users.

As an example, Okami -- the Capcom and Clover Studio game -- definitely got more attention in the U.S., and I think part of that is because of its Japanese aesthetic. It almost feels like an advantage, here. There's a certain interest now in this kind of an exoticism; people are really into that sort of stuff. Western developers can't credibly do that stuff. Do you think that's an advantage for Japanese developers moving forward?

KY: Obviously it is an advantage, but to what extent in terms of market value, is a different thing. If Okami sold like millions of copies, I could say that we have a great advantage, but again, if we're only catering to Japanophiles or whatever, that's one thing. We have the same thing with Ouendan -- people that are interested in Japan kind of like that "Oooh," exotic Oriental kind of, "Hey, that's cool."

I think the reason why it's interesting is the reason why it's not mainstream. I would've wanted to take advantage of that, but then that would lessen the exoticism of it, which is why it's kind of cool to begin with. Especially with titles like Okami or Ouendan or whatever, I think it's important to just really drive it hard, and let the people make a judgment call on that. As to whether it's an advantage for us, it's an advantage in the fact that it's something that we can present that's culturally very close to us, so we can present a lot of the details and have those details come out in a presentation that would not come out otherwise.

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like