Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

The man behind Rez, Child of Eden, and Lumines discusses his picture of the future of games and human perception, and how the concept of synesthesia plays into that -- along with Lumines Electronic Symphony producer James Mielke.

When Tetsuya Mizuguchi followed up Space Channel 5 with Rez, he was putting an aesthetic line in the sand. Built around the concept of synesthesia, or a blending of the senses, the game has become influential and stood the test of a decade.

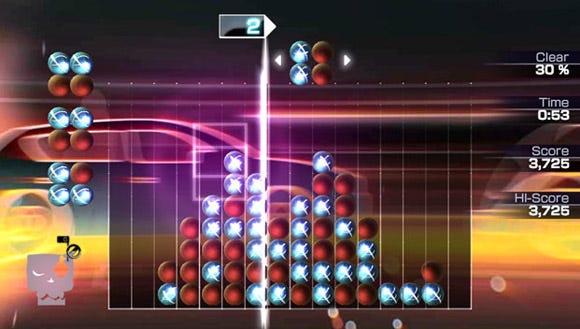

With the PlayStation Vita just launched, his company Q Entertainment has put out a new installment in its puzzle franchise, Lumines. Subtitled Electronic Symphony, it's a journey through decades of electronic music. The carefully-chosen tunes weave a story about the evolution of an artform.

In this interview, Mizuguchi and Electronic Symphony producer James Mielke lay out the creative manifesto of Q Entertainment, and discuss the future of games -- and the possibilities for their expansion into all aspects of life.

The original Lumines was the standout game of the launch of the original PSP, and now here we are again, so it seems like you've come full circle. Can you talk about the inspiration behind bringing out a new one for the launch of the Vita?

Tetsuya Mizuguchi: Lumines is a game we did from the first inspiration of PSP. I heard about the PSP announcement, first. "Oh, this is an interactive Walkman, and we should make a game for the launch of PlayStation Portable, anyway."

I can say that Lumines was a PSP game -- PSP DNA. And we heard about the announcement of PlayStation Vita. "There's no reason we shouldn't make the new Lumines for PS Vita." It's a very simple reason, a very simple reason. [laughs]

James Mielke: And the timing -- we've been bouncing the idea around of bringing Lumines back for a while, but we weren't sure when the time was right, until we heard about the Vita. When Sony first started telling us about that the Vita, was coming we naturally assumed -- like, "Oh, this is probably the best chance to do it."

Because even though Lumines has gone on to many other platforms, like Miz was saying, it was originally inspired and designed for PSP. So it really made sense, it really feels like a series that is supposed to be there with the launch of a Sony handheld.

The first Lumines had an array of music; the second one experimented with some licensed tracks. This seems to be a sonic journey through the history of electronic music. Can you talk about the idea of building a narrative through selection of music, rather than building a narrative through storytelling?

JM: Right. So the game, conceptually -- from when we first decided to do a new Lumines to what ultimately became Electronic Symphony, it went through a few conceptual changes.

JM: Right. So the game, conceptually -- from when we first decided to do a new Lumines to what ultimately became Electronic Symphony, it went through a few conceptual changes.

But the focus was always going to be around electronic music. What I really wanted to achieve with this game was what I was referring to as "Say Anything moments" -- like the John Cusack, boom box over the head.

So in that movie, when he pulls the boom box out and holds it over his head, that's a pivotal moment in that movie, and they're using Peter Gabriel's "In Your Eyes" to great emotional effect. It's a poignant moment in the film, and there's an emotional impact, and it's wordless. It's just the music that's doing all of that work.

So what I wanted to achieve in the course of this game, is I wanted to make something that meant a little bit more than "just" a puzzle game. I didn't want it to be just a game. I wanted it to be a little bit more emotional.

I wanted to put what I call "Say Anything moments" into the game. And so because of that, we were choosing our music very selectively. I think ultimately Electronic Symphony is a little bit less manipulative than we were originally going for, because we really had set pieces that we were going to put into the game. And we were going to put in some music that just would have really taken people by surprise.

It wasn't purely all electronic music, either. I was talking about putting a Supertramp song in at a key point, where certain things would have happened in the game, but the concept transformed a little bit, so it didn't require us to do stuff like that -- but that was the original inspiration.

I know both of you well enough to know that you both feel very strongly about the power of music to emotionally effect people, so that's something I want to talk about. Have games been an effective medium for the emotional context of music? I know you've tried with Child of Eden and Rez, in particular, to make music effect people emotionally. Have you achieved what you wanted to achieve?

TM: That's a good question. That's a deep question. We listen to music in life, and watch music videos. But if you watch a music video five times in a day, and 10 times you listen to music -- the same music in one day -- that's getting boring. But the game is a really good art form, a really good medium. And if you feel the music interactively, and if you play the game and it feels fun, and you get the music, you not only use but feel the music.

And so our approach is not a timing game all the time. You play the game as a game, and as a result -- as a reward -- it's going to pay off. You get the music. I think that this approach, I think it's very unique, and it's a new way to enjoy music.

Technically, we can do that as the game. So I believe in that kind of power of the game, and the possibility of synesthesia. And it depends on the changing of technology, which is getting high. Ten years ago, we could just start to make synesthesia like Rez, but now we can make much more. We can put much more high resolution and get high synesthesia. I can make some much more rich storylines in Child of Eden.

And also the new Lumines, James Mielke, he made a really good music list, and this is also kind of a journey of music, and so I think, in the end, this game is better than the first Lumines.

JM: Yeah it means a lot to me to hear him say that. I think we won't be able to really say definitively what's the best one until maybe some years have passed, and it's really soaked in.

I think one of the things that we want to do with music is have it really matter. With Electronic Symphony, it's really a celebration of electronic music from the '80s to now. If you look at a typical licensed music scenario, like maybe a skateboarding game, whatever publisher or developer is making it, they'll probably license like 15 to 20 thrash metal tracks, and it's all just background noise.

But for us, our musical selections are much more integral, much more meaningful. We pored over the musical selections that we're putting into this Lumines for at least six months, and we went through a lot of trial and error, a lot of rearrangement, and we wanted to make sure that every song had a real meaning, and a real sense of context in the game. We put a lot of thought into what we're choosing, musically.

You started out, when you made Rez, with this core concept of synesthesia. How close have you gotten to achieving synesthesia in any of the games you've released so far?

TM: Original inspiration?

Yeah, your original concept of what synesthesia could mean in the context of a game.

TM: To be honest, in the case of Child of Eden, I had a much more organic, much more physics-based... Everything is moving with the sound and the music, every visual effect reacts by the sounds. I wanted to put much more physics elements into it.

I'm not satisfied yet. [laughs] So maybe in the future. I think we can make, much more, how can I say it... The physics, organic, audiovisual experience. Much more blended, and kind of a fusion. I want to make it, so...

JM: What do you think is holding it back? Is it the technology? It's not there yet?

TM: Technology, and if I can work with the new type of people. All programmers, but they have a sense of the arts and a synesthesia feeling, so maybe it is possible.

Do you think easier development tools that allow people who don't have a technical background to work on games could bring more to it?

TM: I see the future game of synesthesia made by the programmers and coding people, more than artists.

What makes you say that? Why would programmers have a better handle onto it than artists?

TM: Programmers who have the art sense.

People who can travel in both worlds, is what you're saying? People who understand both sides of the equation?

TM: Yeah, yeah.

JM: That's a rare programmer, too. This comes up at Q quite a lot, because the lead programmer on Child of Eden is a programmer who is able to think visually, [Osamu] Kodera-san. That's a rare exception in the programming field, generally speaking. Because most programmers, if we want to communicate something to them, if we say, "We want the end result to look like this," sometimes we'll have to do a proof of concept, we'll have to visualize it, we'll have to do illustrations, we'll have to do some kind of tech demo, sometimes, in order for the programmer to understand, "Oh, that's what you want me to achieve."

But when you get a programmer like Kodera-san, you can just tell him the idea, and he already can visualize it in his mind, and he just goes to work. So that, I think, is what you're really looking for. Those kinds of visually-minded programmers.

Especially with a relatively small company like Q, I would imagine it's very important to be really selective about the people you bring in, and that they understand the vision and the mission of your company. Has that been a challenge? Getting the right people?

TM: Yeah, always. It's a challenge. It's not so easy.

JM: Yeah, for those exact reasons. Trying to find that kind of programmer, who thinks like that -- those are the best programmers. Those are the ones that are hard to find. Because once they do emerge, there are so many game development teams out there, so they're in high demand. So finding those kinds of guys... they're out there. But Japan is not a huge country. Sometimes you have to look overseas to find the right talent.

TM: We need to find a new way to work together. Using the cloud. This is the new style of development. I think so. Definitely, yes.

You said you wanted to bring more storyline into games, along with synesthesia. Child of Eden had the whole story of Lumi, for example. How do you feel about cinematic narrative? Do you think that that is something you want to pursue, and how far do you want to pursue it?

TM: The game is game -- so a fun game doesn't need a story, if the game is fun. But this is old-style. This our challenge, always. Okay, let's combine the new -- combine the puzzle game with some kind of a narrative. This is kind of a really ridiculous thing -- why the puzzle game needs a story. We want to do that all the time -- this is a challenge.

So the first Lumines put the narrative with music, and the music video kind of explained it. We could do that. This is a fresh combination for us, and a new challenge. It's not easy, but we need challenges all the time.

Rez is a very strong experience, stimulation. And we wanted to try another challenge, blending the story into that kind of experience. So finally, if you play the ending of Child of Eden, what do you feel? So all the time, we have that kind of challenge, and we want to go farther. What is the future of games? And people need a story all the time.

JM: But at the same time, we always have to think about the balance of things, because why do people watch movies? Because they want to relax, and they want to see an interesting story -- they want to watch special effects, cool action scenes, whatever. You get emotionally evolved, but it's still kind of a passive entertainment. Why do people play games? Because they actually want to play something.

So just because we can start doing Hollywood-level cinematics, does that mean we should, at all times? Would it be prudent for us to interrupt the game flow of Lumines Electronic Symphony with a 45 minute cutscene in which you can't do anything but watch, and it's unskippable? No, because then we're starting to impose an obnoxious vision on people, so we have to maintain the balance as well.

Like I said, for Lumines, we have a bit of a narrative going on, and a theme, but it's not something that hits you over the head, or it's immediately apparent. But the more you play, maybe you start to feel something. Maybe you feel homesick by the time you get to the end of the Voyage Mode. You start feeling homesick for the beginning.

So then you feel like you've taken some kind of emotional journey and it's a story -- it's almost like reading a book in a way. You read the book, and you imagine it -- versus seeing a movie and having it literally spelled out for you, where you can't even imagine it any other way. Storytelling takes on lots of different forms.

We've definitely seen with music video that you can tell stories and have music at the same time, and you can do it in a way that doesn't involve dialogue, that doesn't involve a full application of movie storytelling technique. Is that something that interests you?

TM: Every piece, we design, in the game. So, for example, Lumines -- every element, every moment has sound effects, visual effects, some video effects, and every piece has a meaning, and this is like a poem. Something full and raw will take, and disappear, and every moment, you get some meaning. This kind of meaning is making a chemistry, that's like pieces of words. It's like a poem. So making something that has chemistry, I love this kind of form.

So some people say, "Oh, Lumines. How amazing is this game? It's not the one I want to play from the beginning to the end." But some people are disappointed.

But people play Lumines. Everybody knows "Oh, that's not just one time -- I want to play many times, and play, play, play, play, play, and then, finally, I feel something, emotionally." And that kind of emotional something changing -- I think the first 10 times, maybe 400 times, and then you can get something. So yeah, I love that -- that kind of feeling.

JM: Yeah there's a take-away. You know you're only a puzzle game, if you want to really dress it down. Seven years later, people are still talking about Shinin' from Lumines 1. They're always saying, "Oh, is Shinin' in Electronic Symphony?" And when we say, "No, it's not," a lot of people are disappointed, because they want to play that. Why do they want to play it? Because they remember it. They walked away from that game with something. So we're trying to create new memories with this, in our own particular way.

Famously, you originally started out at Sega, and you worked on Sega Rally, among other games. You have an arcade background, and this really sounds like the continuation of that. Arcade games are games where you play the same game repeatedly, and the play same thing, and you get caught up in it, and you get caught up in that feeling.

Speaking from a game design perspective, are you still carrying that legacy forward in your designs? Because I feel that Rez and Child of Eden are the same way. Like yeah, they're quote-unquote "short" games, but I can't tell you how many times I've played Rez in the last 10 years. It came out on Xbox Live, and I bought it again, and played it again. Even though it's short.

TM: It's the same DNA, all the time. Yeah, my DNA never changed. But it's impossible to bring Child of Eden into the game center, because it's too long for the game center, location-based.

[Ed. note: "game center" is the Japanese term for "arcade."]

But yeah, I can understand what you're saying. Yeah, I got experience with those games. All the time, we're watching the people playing the game by one coin, and three minutes, and watching their reaction. And it's like, "Yeah!" [pumps fist in victory] or it's like, "Ngh!" [mimics someone reacting badly to a defeat]. Like that. That was a really good experience for me. How can we design an emotional current? Feeding the people's tension. Excitement.

Tension and release. Is that something you designed for very deliberately?

JM: We're always talking about cause and effect, so there's a feedback. Call and response.

TM: Call and response, yes. For the last 10 years, I've been focusing on music-based games --music is call and response all the time. They're playing instruments together, all together, and when they're making a group, somebody starts the beat, and they follow the beat, and together become one.

So that kind of process is very organic, but if we watch the detail, everybody doing call and response -- a beat, and somebody hits the response, and reacts with something. If you're making some interactive coding, we need to cut, divide everything.

You mean divide everything into like musical notation, essentially? Or beat structure?

TM: Yeah. And that kind of process, I found, the call and response in the music can merge with the gameplay. The game is also call and response. That's the similarity in music and games. So this game is our style: Rez, Space Channel 5, Lumines, Child of Eden.

JM: For you, it really started with Space Channel 5. Ulala or the Morolians would make the sounds like "Up, up, down, down, chu, chu, chu, chu," and then you'd have to press the appropriate buttons.

But with Rez, and Child of Eden, and Lumines, it's much more subtle than that. When you press a button, you get a sound immediately, so the payoff is there, so you constantly feel involved. With Lumines, every time you rotate the block, there's a sound effect custom-designed per song to accompany that rotation. When the timeline passes and clears blocks, there's a custom sound designed for that. There's been such a focus on that in Q Entertainment that it informs every element of our design now.

Do you think people are thinking musically when they play your games?

TM: Child of Eden and Rez, this is a playing music feeling. Space Channel 5, this is a musical. The player's enjoying the narrative dance, and, I think, the much more wider wave of call and response. It's got a totally different mechanism, essentially.

JM: But is the feeling of player feedback, is the call and response greater in games like Child of Eden because the interaction is very fast?

TM: Yeah, Child of Eden, yeah, that style of game is speed gaming, and so it's like magic. Connecting my hands, my body, connecting to the game itself. If I do this [moves hand] I get sounds. That kind of feeling is very important, to immerse people.

Since the original Lumines came out, I think game culture has changed a lot. There's a lot of different people playing games now. How has that affected your company, and how does that affect the way you approach games?

TM: In these seven years? So many more people playing now?

Yeah.

TM: Like on their iPhones.

Because I know that you know when you made Rez, you threw parties in Tokyo, and as I recall, you were talking about how you wanted to bring in people who understood music and aesthetics to games. Do you see that as an opportunity now?

TM: Yeah, games are expanding. Six, seven years ago we had just a few platforms: PS2 and Nintendo, Xbox, and PSP, DS. That's it. No mobile phone yet -- no smartphones.

And now, so many people are playing mobile phone social games, and free games with unknown people. So no stimulation, but they've enjoying some social connection, and this is also a game. And it's all chaos now. It's chaos.

JM: It's hard to know what the right thing to do is nowadays, because traditional game development is nice and all, but you're seeing companies, the resources they devote to games is so small, but the payoff is potentially so large. A lot of companies want to make 10 games in the time it takes to create one old school game, and any one of those ten games could make 10 times as much as that old school game. Especially for the amount of money invested.

TM: I'm teaching at the university in Japan, and I'm asking the students, "Do you play games?" And even if they're the core gamers, now they're playing social games on a mobile phone. They play both. I think the time to play console games is reducing.

I think that we can say, "Oh, the game industry is expanding." We can say that. It's that many people are getting a kind of cheap variation -- everything is getting cheap. It's like free games, and microtransactions.

People feel all the time, "Oh, we are busy, and I don't have time to play a game anymore like that," and then they want to play the game, so they think, "Okay, I will play a mobile phone game, just five minutes, now." And this is free-to-play, and just 10 percent of people pay the money. And that's a new business structure, and so that's a big change -- a big change.

But all the time we have answered the consumers. So they want to play high resolution games, or high-end games... but if they have a very cheap free game, now, they can play 10 minutes and they will be satisfied. So this is a big dilemma in this industry.

But this not the final form, and this is not the answer yet. This is a transition. But I don't know the future. But all the time, this is a kind of a mirror of human instincts, and wants, and desires.

Well you can cater to your impulses if you play on a phone. It's like eating a candy bar instead of eating dinner, right?

TM: Yeah, right.

You make games that speak to a wider audience than just hardcore gamers, but these games that you're talking about are even further from the kind of games you make. If you make a game for Mobage or GREE, you're not going to be able to make something like Lumines, let alone Child of Eden. You can't make something that demands attention from the player.

TM: What do you mean?

Because they can't sit down -- they can't get into it. Lumines requires an investment.

JM: Yeah. Time.

Time and...

TM: Concentration. Yeah. Yeah, you're right. I've head that some young people in Japan can't keep up with a two hour movie. [laughs]

JM: That's sad. That's disturbing. They can't sit still for a two hour movie.

TM: Yeah. The same thing in the United States?

I don't know about young people, but I do know that if I'm watching a Blu-ray at home, without thinking about it, I'll grab my iPhone after half an hour, and I'll pick it up. And then I go, "I'm an asshole," and I put it down. And then about half an hour later, without thinking again, I grab my iPhone.

JM: We're so distracted, and we're so hungry for constant information input. We want to see what's happening on Twitter, or whatever.

People can't put that kind of concentration into a web browser-based game, it's true. I wouldn't say it's completely passive, because you are actively clicking on the button, but there's very little there worth clicking on, so it's practically a passive thing.

Even with something like Lumines, we put so much work into the audiovisual presentation, and there's a reason for it -- because we want people to look at it. We want people to listen to it. So therefore, I guess, just by default, we are expecting a certain level of attention when you play that game. And of course, if you're not playing attention while you're playing Lumines, you're going to Game Over yourself real soon. So that's probably part of it.

We attempt to make high quality products. You can't passively play Child of Eden, especially on Kinect. You've got to be in it to win it or else you're going to be looking at the retry screen pretty soon. So yeah, different games for different types of people. That bored secretary working in a dentist's office staring at Angry Birds, or FarmVille, or whatever, that's totally designed for that need. So it's a case-by-case basis, but as Miz was saying, it is chaos.

Lumines: Electronic Symphony

Do you think that something good is going to come out of the chaos. or do you think that something bad is coming out of the chaos -- or neither good nor bad, just a new reality?

TM: I suppose no good, no bad. This is reality, yeah. We need to face that reality, and we have to think about what is the next reality. And we need to design, we need to make, and we need to pull the people to the new future vision.

JM: We're forced to react to it because, a lot of the traditional console game development dollars are being rerouted en masse to social gaming, because it's a gold rush right now, so everybody wants to be in that space. Some people are really innovative about it. Some people are horribly slavish to the conventions that have been established by Zynga, GREE, and Mobage. All those Evony clones out there. So the challenge is to be successful in that space, but to try and innovate at the same time.

TM: And also, we can see everything moving to the cloud. It's kind of the world of Google. Everything in the network. And this is a very logical state, and it's not so physical yet, but our brains, ourselves, all the time, we need the balance of the physical and mental states.

I think that in the future, we need to bring a synesthesia feeling into it. If we are using the tablet, and if you touch something, there's a much more synesthesia feeling you can get. I think there's a balance. So maybe many, many things we can control by gestures, the camera watching you. But we need that kind of a physical something. How? This is our challenge.

JM: Miz and I were talking a lot about this recently. When we say "synesthesia", it's not just in that trippy, conceptual manner. For us, synesthesia is giving people pleasurable feedback. We're not doing it through force feedback -- this thing [indicates the PlayStation Vita] doesn't have force feedback. So how do we reward people, and their senses? We do it with visuals; we do it with sound.

This concept stands in the real world as well -- like if we were to take our philosophies, and try and design a refrigerator. What if there was this refrigerator handle, every time you touched the handle it glows warmly? What if there's like a certain sound if you touch the handle to open it? What if you hold the handle up at the top, maybe the sound's a little bit different? What about when you open the refrigerator door, what if there's a synthetic sound that sounds something like a sigh, so it's like a welcoming sound, when you open the refrigerator? What if when you close the refrigerator door, where there is that seal, what if there's a warm neon orange glow, that's subtle, or it changes depending on the time of day? We were talking about that.

So these things are all just ways to make people enjoy what they do, what they interact with. If things that you take for granted every day -- like a light switch, when you go into the room and you flip on the light switch, what if when you touch the light panel, it glows gently in response to your touch? There's a feedback there. So when we talk about synesthesia, we're thinking about those kinds of things.

That makes me think of Toshio Iwai.

TM: Oh, yeah.

Doesn't it make you think about his stuff?

TM: Yeah, he's really good. My friend.

Are you really good friends with him?

TM: Yeah.

I'm not surprised to hear that.

TM: Yeah. We've been forover 20 years. Yeah, he's a really good friend. He's a true artist. A media artist. I have kind of a similar concept -- but my stage is the interactive game. But we need that kind of elements to go into the network. And as James mentioned -- it's like how he mentioned about the refrigerator. [laughs]

In life, we need that kind of thing more and more. I believe, that kind of concept, we can expand to life -- all life. I think the game, itself, may be expanding. Some people mentioned about game education. This is not the final concept, but games are getting changed, and blending through the whole life as water, air, kind of things. It's a very natural thing, in the future.

That makes me think about Area 5 in Rez. Evolution. You're talking about games expanding into the network, and our perceptions expanding into the network, and of course that immediately makes me think of the story of Rez, and the story of Child of Eden.

TM: Yeah. Mm-hmm.

It's the same concept.

TM: Yeah.

Do you see those stories as actually maybe being more true to the future you envision than maybe people thought when they played the games?

TM: I don't know. [laughs] This is one of my...

JM: Prophecies.

TM: My story. All of them, I hope. We want to go the positive way, not the negative way.

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like