Elan Lee's Alternate Reality

42 Entertainment vice president and alternate reality game designer Elan Lee (I Love Bees, The Beast) discusses the future of this unique genre, 42's business strategies, and alternate reality's secret origins in a Beatles album.

Elan Lee is the vice president of alternate reality game powerhouse 42 Entertainment. His resume includes sensations like The Beast and I Love Bees, as well as new experiments like EDOC Laundry and Cathy’s Book.

At the 2006 Montreal International Games Summit, Lee led an introductory session on ARG’s. Afterwards, we sat down with him for a brief interview.

Gamasutra: The Beast is widely considered the very first ARG. Would you agree?

Elan Lee: No, I consider the first ARG The Beatles’ “Sgt. Pepper's” album. Of course, it depends how you define an ARG. My definition is very loose. An alternate reality game is anything that takes your life and converts it into an entertainment space. If you look at a typical video game, it’s really about turning you into a hero; a super hero, a secret agent. It’s your ability to step outside your life and be someone else. An ARG takes those same sensibilities and applies them to your actual life. It says, what if you actually were a super hero, what if you actually were a secret agent? Instead of living in the box that’s your television or your computer, why not use your actual life as a storytelling delivery platform?

GS: You mentioned “Sgt. Pepper's.” Was that one of your inspirations for The Beast?

I mentioned the album because that’s really, for me, where it started. They embedded a bizarre series of clues and mysteries into the cover, turning you into something more than you previously thought of you were. Look at this album: There’s a phone number hidden in the bushes over there. What would happen if I called it? Your superpower is simply that you notice this cool thing that most people don’t notice.

GS: Did the clues on the album cover actually lead somewhere?

GS: Did the clues on the album cover actually lead somewhere?

EL: There was no internet at the time, so people weren’t able to form large-scale teams, but a lot of people went through the experience, and there are rumors that they solved the mystery of whether or not Paul was dead, and they figured out this secret island that the Beatles created somewhere. It all lives in rumors, of course, and I wasn’t even alive at the time, so I have no actual idea, but it’s something that I read about and thought, there’s something here. There’s something very empowering about saying there’s a little bit of magic in this world, and if you pay attention you’ll find it.

GS: Yesterday, during your talk, you also mentioned the Michael Douglas movie The Game as an inspiration. Where does that fit in?

EL: That movie completely twisted my mind. I have this terrible lack of ability to predict the end of any movie. I sit there, completely gullible and taken in by the movie makers. Anyway, I got to the end of that movie, and I was blown away, because I didn’t see it coming, at all. And I thought, there’s something magical here in the ability to take someone’s life and transform it into an entertainment platform. The movie got really scary and creepy; we wouldn’t actually want to do that, but on a much smaller scale there are some really fun things there. What if you’re walking down the street and a payphone rings. This is something that has happened to me tons of times. I travel a lot, so I’m always walking through airports, and inevitably a phone will ring. I always run over to answer it, thinking, what adventure lies in store? And it’s always a wrong number, a telemarketer, but every time I have that little moment of hope: Is an adventure about to start?

Alternate reality games attempt to deliver on that potential. Everyone wants to believe that they have the capability to live that secret agent life. Oh my god, a phone’s ringing! Maybe it’s someone who needs to talk to me because only I can save them. So we try to say, yeah, only you can save the day, and that phone ringing is for you, so answer it.

GS: Yesterday you also talked about turning your players into heroes, but it seems that your games are more about discovery than heroism, maybe even self-discovery.

EL: I think maybe I should find a better word than “heroes.” With heroes, everyone imagines someone wearing a cape, and that’s so not what I mean. Anyway, most games are all about pushing a message, pushing a fiction, pushing a set of characters. It’s very aggressive. That sense of discovery is so important for ARG’s because if, instead of shouting, instead of pushing our message at people, if we whisper it, if we just embed a small flash of imagery in a TV commercial, if we do something subtle, it could be so much more powerful.

You, who discovers that bizarre frame that’s out of place on the TV, suddenly you own that experience. It’s yours. You feel this tremendous sense of pride, because you found it. And you’re so much more encouraged to tell your friends about this, because it isn’t something someone threw at you. This is something you pulled.

"Evan Chan was murdered. Jeanine was the key."

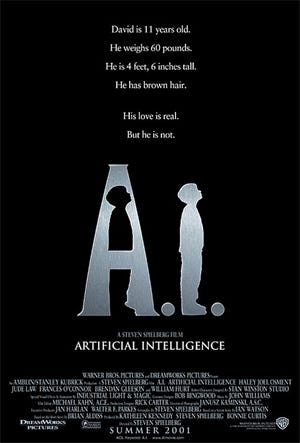

GS: When you first got started, before there was really any precedent for this kind of game, how did you know people would play it? For example, The Beast kicked off with notches in a date on an AI movie poster. How could you be sure anyone would catch on?

EL: Absolute luck. I wish I could say there was this science, this beautifully formulated equation, but, no, we just guessed, and we got lucky. There’s a lot of psychology involved in games like this. No one’s done this before, so we can’t go the library and check out a book or find a reference on the internet, we just have to say, I would think that’s cool.

GS: Have there ever been symbols that the players totally missed?

EL: We’ve had tons. On the AI project, we wanted to embed a puzzle inside a map, and so we said, all of the physical locations of everything we do in The Beast, if you blocked those out on a map, it would spell a word across the United States, and that would be really cool... Yeah, no one ever saw it. We had such high hopes. You know, I say whispering is more powerful than shouting. Well, sometimes it’s too quiet of a whisper.

GS: Are there certain kinds of messages that get picked up and kinds that go under the radar?

EL: We’re sort of learning as we go. I wish I could plot out this graph, because the way it actually works is the more subtle the message the longer it takes for people to discover it. So it all really depends on your time frame. If you have a year-long entertainment experience, then you can afford to be really subtle, because there’s this wonderful “a-hah” moment when somebody says, oh my god, this has been in front of us all along. If your project is two months long, two weeks long, you’ve got to a lot more obvious. It’s a balancing act.

GS: Playing your games often requires a lot of hard work and searching, but people seem more than willing. What do you think makes players so dedicated?

EL: When the Cloud Makers, the number one fan group for AI, formed, their mantra was “Lowering the productivity of the American workforce, one person at a time.” When you say people are constantly devoted though, you have to be really careful, because 95% of our players are not that way. They check in on the games very rarely. What we’ve found is that, there are too really appealing factors to immersive games, something that takes over your life. One is... that it takes over your life. The other way is, with the fanatics, their activities are almost more entertaining than the game itself. So it’s a circle of people who are willing to throw themselves at the experience and then the people who just like to watch.

GS: In the case of I Love Bees, players were getting phone calls from the game in the middle of the night. Especially for the fanatics, where do you draw the line between game and life?

EL: The last thing we want to do is to make an experience that’s indistinguishable from real life, because while it seems like that would be a good goal, it’s actually so scary that it becomes really unattractive. We’re very careful to always insert a small element of the fantastical into our games, because we want people to be able to make that distinction. You don’t want a game that takes over your life. You want to be able to opt into the experience, and control how much of your life is devoted to that game. It’s a fine line, and we’re very conscious of it.

GS: From your end, how do orchestrate some of the more elaborate game elements, for example calling payphones across the world?

EL: It’s a pretty massive effort. In I Love Bees, when we called up several thousand payphones, initially the thought was, hey, you know what we could do is we’ll just find an internet resource for payphone numbers, thinking, this will be easy. We found that there are such databases, except the payphones, no one maintains them. Half of them are non-working numbers; the other half don’t accept in-coming calls. A lot of them are physically disabled or torn out of the wall. Then we realized what we’ll do it call up the phone companies and say, hey, give us a list of phone numbers for all your payphones... Yeah, phone companies don’t want to give that information. What we had to do in the end was hire teams to hand verify every single phone that we called around the world. It turned into this massively time consuming project, but we just couldn’t find another way to do it. I think, if we had known that going into the project, we would have said, payphones, no way, let’s use something else. Again, no one’s done stuff like this before, so we either have to make up the rules as we go along, or make enough mistakes that the right answer eventually becomes apparent.

GS: What about the crop circles you executed for Hex 168? How do you even begin to arrange for something like that?

EL: We have a very, very talented team. They call themselves producers, but they’re kind of like little miracle workers. I am in this lovely sort of ivory tower, where I say, "you know what would be cool, is crop circles," and then this amazing team of producers says, "yeah, we’ll figure that one out." I couldn’t tell you how they do it. I know they have connections, and they make a zillion phone calls, and they’re really good at searching the internet. Amazingly, they always find a way to make it happen.

"HEX creates a monkey mogul," A winning Hex 168 entry.

To be fair, sometimes I ask for things that are just too hard. Back in AI, the challenge was, hey, let’s build the game in such a way that your life just gets weird. The producers came back to me and said, what does that mean? I said, I want you to look at the web, and suddenly nothing quite makes sense anymore. And they said, well, we could do a little pop-up window. I said, what I want is, after you visit this website, your car only drives in reverse and none of your friends remember your name and suddenly your mom doesn’t speak English. And they kind of gave me this blank look and I said, yeah, I’ll settle for a pop-up window. So sometimes imagination gets the best of me.

GS: How did you end up in this position after working in game development for Microsoft?

EL: When I was at Microsoft, I was terribly miscast as a producer. I thought, hey, this is what I should be doing. Then I met Jordan Weisman, who was the creative director of the games group there. Jordan is my mentor. Jordan is the most creative, amazing person I’ve ever met. We sort of hit it off, and we had this discussion about the future of games one day. I remember we were sitting at this restaurant, eating sushi, and at that moment his phone rang. He looked at me and said, wouldn’t it be cool if that was a game calling me right now? And that’s kind of where it all started. When we started talking about that, Jordan realized, you suck at producing, and he moved me to the design role, and from there we met with Spielberg and created AI, and from there we created 42 Entertainment, and from there we started EDOC Laundry, the t-shirt company, and it’s just been this crazy snowball of events since then, finding this bizarre talent that I have that would be absolutely useless in any other field.

GS: A lot of the ARG’s you’ve worked on have promoted a product. What’s the relationship there? Do you feel the games have been successful as marketers?

EL: Our role for marketing is not a traditional one. Typically marketing tries to get more new eyeballs on a product. What we try to do is get a product into venues they wouldn’t normally have access to. For example, we did I Love Bees for Halo 2. Halo 2 was going to be huge, no doubt about it. But suddenly you saw crazy, fanatic people answer telephones in bee costumes in the middle of a hurricane; you saw that on CNN and you saw that in the New York Times. You saw stories about insane Halo fans interacting and creating entertainment in their lives in a way that no one had ever seen before. And while Halo 2 would have been huge anyway, there’s no way it would have gotten into venues like that.

GS: But did that big-name coverage mention “crazy Halo fans” or “crazy I Love Bees fans”?

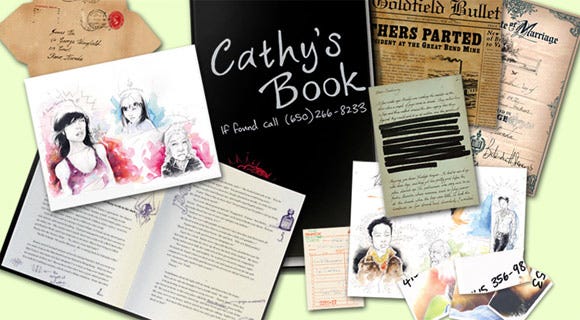

EL: Most of the articles I saw mentioned Halo 2, because it these bizarre statements that reporters have to make in order to cover the story. So in that sense we’re very valuable to our clients. But, while we’re getting very good at marketing, we’re really interested in branching off. And that’s what EDOC Laundry is--saying, hey, we don’t need to market anything but our own stuff. We just released a book, called Cathy’s Book. What if we did this for ourselves? Can we actually make games and stories that don’t promote anything else? Next year you’ll see a few more experiments leading toward that eventual goal of creating a new genre of entertainment that doesn’t have to support another genre.

"Decay," from EDOC Laundry

GS: But EDOC Laundry is still very much based on selling products.

EL: You’ve got to make money somehow. It seems that your options are sell a product, or charge a subscription–Majestic was a previous example of that, and it didn’t work so well. We are looking at more creative subscription models–or in-game advertising. No one’s really tried that last one yet, so that’s one thing you will definitely see some experimentation with in the future.

GS: How would in-game advertising work? Don’t you run an ethical risk in a game that’s already so subliminal?

EL: For our games, where people strive to make them real, the more things you can do to make them feel good about believing that they might be real, the better. We’re in this unique position where things like product placement are actually a good thing, because the more real-world examples that can fit into a game, the more comfortable users feel saying, I’m willing to take the leap of faith that maybe there is this alien invasion, because it’s grounded. We’re going to try to take as full advantage of that as possible.

GS: Back to EDOC Laundry for a sec, could you talk a bit about the structure of the game itself? Yesterday you explained how players find codes in the clothes they buy and then plug the codes into your site to see clips of a murder mystery, but how are players interactively involved?

EL: The current model of EDOC Laundry is exactly as you described. It’s a very passive experience. Initially, we just wanted to run the experiment: Can we create an internet portion of a clothing company? So we made this sort of hunt-and-click experience. You go out, you buy a shirt, you get the code, you punch it into the website, and you get rewarded immediately. The theory was, if you watch enough of the movies you’ll figure out “who done it.” In the next season, coming out this week with our new range of winter clothing, you’ll see a much more interactive process. You’re actively participating in the story, actively solving puzzles, with still the fun and rewarding goal of trying to figure out a murder mystery.

GS: What about Cathy’s Book? Where does that project fit into this question of game vs. product?

EL: Cathy’s Book is another wild experiment. It’s on the New York Times bestseller list right now, which is very exciting for us. That sort of validates a lot of the assumptions that we made about the product. It’s a very, very early step. You buy the book, and it serves the absolute goal of being a book. It’s entertaining to sit down and read the thing. When someone says, I called Joe to see what the deal was with blah, well, there’s his phone number, you can call Joe yourself and see what the deal is with blah. It’s kind of like fiction enhancements–just a little bit more real. When we talk about a photograph that Cathy grabbed and tore up, as you flip through the book, there is that photograph, torn up in pieces, and the fun part is you can put them back to together and flip it over and see a phone number on the back, which you can call, which leads to the next part. But the interactive model kind of ends there. There’s no mystery that you can solve that the book won’t on it’s own.

GS: So the story is an end in itself?

EL: Exactly. But again, this was just version one. We wanted to try, can we create real world examples to enhance the storytelling process in a way that people are comfortable with? You’re comfortable sitting down, reading a book. Future versions will build more on that. We don’t want to abandon the concept that, hey, a book is fun just to read start to finish, but we’ll be able to provide more interaction, and make that interaction more relevant, and more important, without which, things will not happen, parts of the book will actually not resolve themselves until you take action to resolve them.

Cathy's Book

GS: How will that work? A book is there, in your hands. You can’t block off certain sections.

EL: We look at it as, there’s the plot, and then there are subplots. The main plot is something we’ll always lock down. It’ll always come to a satisfying conclusion by the time you get to the end of the book. But those subplots are things that we can really experiment with, and that’s what you’ll see in version two. Version three will be far more experimental.

GS: How important is writing in your games? Even beyond Cathy’s Book, there seems to be a narrative behind all the work you’ve done.

EL: One of the partners of our company is a guy named Sean Stewart, an award-winning science fiction/fantasy novelist who is, in a very real sense, the backbone of most of our projects. Without the narrative, we have really good delivery platforms, but no story to deliver. Sean pushes our stories forward in a way that brings them to life. Fifty percent of our players are female, which is unheard of for video games, and I would argue that the main reason for that is our stories rock. That’s Sean Stewart working his magic.

GS: Is that fifty percent of all players, or of the hardcore fanatics?

EL: It’s hard to say exactly. We don’t actively pole our users. What we do instead is we find out what communities already exist, and we monitor them very closely. Even in the core, like the hardcore gamers, when they run their own self-poling, they’re fifty percent women. It’s really unexpected. But it makes us very happy to see because it means we’re firing on cylinders that most games leave idle.

GS: You had mentioned the Lost ARG as an example of an unsuccessful ARG. What do you think went wrong with the experience?

EL: It’s not that I disliked the experience, I disliked the implementation of it, and I think the distinction is very important. I personally monitored Lost very, very closely, and was watching the community and watching the players and playing it myself and trying to be thorough in my analysis of what went well and what went poorly. Lost made an assumption that I know I personally am guilty of time and time again, that a given activity that is fun will continue to be fun when it’s repeated a large number of times. It’s something that you need to course correct from.

In the case I Love Bees, when people got bored answering pay phones over and over again, we started making live phone calls, and we did actual games online, and changed up the game model because we didn’t want it to get stale. Lost never quite captured that. While their story was good, their delivery never changed, and people got bored of it. Just looking at the people contributing actively, it seems clear that their numbers took a steep fall.

GS: Lost itself seems to have an ARG-like quality. Do you see a connection between shows like Lost and the rescent rise of ARG’s? Maybe something in the air?

EL: Absolutely. A lot of this has to do with the internet. Because communities form and talk, television producers and game producers now have access to these discussions, and they see that their audience is a lot smarter than in the past they’ve been given credit for. As a result, people are willing to take a lot more risks. Lost is a great example. They’re constantly forcing the audience to make speculations. I’ve been watching Heroes lately, and finding the little half DNA symbol all over the place is a fun, engaging activity. If you look at the communities hypothesizing about it, you can tell in the script writing, there are producers watching those conversations, because storylines and the characters react to exactly what the community is talking about. Because of that access, there’s a lot more trust, and a lot more experimentation.

Read more about:

FeaturesAbout the Author(s)

You May Also Like

.jpeg?width=700&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)