Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Gamasutra speaks to Tarn Adams, creator of the iconoclastic and unique simulation game, about his future plans, why he doesn't fraternize with developers, and why he resolutely refuses to sell out.

July 2, 2013

Author: by Mike Rose

This post has been highlighted as one of Gamasutra's best stories of 2013.

"What we've done is lay out a framework for version 1.0, and you just have a giant piece of paper with everything on it, and there's the stuff that's on the paper, and there's the stuff that's off the paper."

Tarn Adams and his brother Zach have been working on procedurally-generated fantasy game Dwarf Fortress for around 11 years now, although if you include the DragSlay and Slaves to Armok development work that preceded it -- and essentially molded the game's early beginnings -- it's more like 13 years.

Although you can download and play the game for free right now, version 1.0 is still a long time coming. Tarn Adams recently estimated that we can expect 1.0 in around 20 years' time, although he admits it'll probably take even longer than that, "because I always underestimate release times."

But the Adams brothers have a clear goal, regardless of timeframe. The duo recognize that they have gotten stuck in plenty of development ruts before, and their solution is to lay everything out in front of them, and decide on what will make the cut.

"We try to stay on the paper as much as possible," says Adams. "When we finish the paper, that's 1.0. And there's a whole lot more to do after that. I mean, obviously, if we're in our 50s, we'll have all kinds of life decisions we're making, so there's no reason to think that we'll stick with this plan for even another five years or whatever."

But that's the general idea -- sticking to the plan without getting too deep in the weeds. "Just kind of lay out a skeleton, flesh it out a bit, but not put the little curly hairs on it like we did in the first version of the game, where we had curly hairs on every part of the body, and measured their exact flash points and everything, and you could teleport someone's nose off and so on -- although we're pretty much there in Dwarf Fortress again."

What's so intriguing (and perhaps questionable) about Adams' 30-year-plus plan is how exactly the designer can stay focused and enthused about a project that may potentially take up his entire adult life.

I regularly talk to developers who tell me "I've really enjoyed working on this game, but I cannot wait to get it behind me and work on something new." How, then, does Adams keep up the enthusiasm for Dwarf Fortress? Isn't his attention starting to meander to other projects?

"Not really," he answers. "I mean, if we didn't have vents for things like that, then I think it'd be a realistic expectation. But having put in the years, I kinda know where I'm at. And I kinda know I've made time for myself to make side projects, even though I haven't released anything since Dwarf Fortress that wasn't related to Dwarf Fortress... like the Cobalt Quest, the Mac porting project, or whatever."

Zach and Tarn Adams

In fact, Adams says that he has around seven other big projects that are sort of in the works but not -- "they are all sort of large undertakings that I don't have large undertaking time for," he says. "There's time when we're watching stupid stuff on TV over at my brother's place where I have my other laptop, and I work on those games, just as kind of a break."

"We don't really talk about them that much, and don't say what they are," he continues. "We don't want to build any hype for them because it's not necessarily anything that's ever going to see the light of day. It helps, though, to know that we still have other ideas that we can work on, and there are lots of other interesting things to experiment with."

There's another reason why the Adams brothers don't believe they'll ever get bored of Dwarf Fortress development -- the sheer scope of the title, and the ridiculous number of avenues that they can potentially go down at any given point.

Adams says that whenever he becomes bored of a specific element of the game, he can simply go off and work on something else completely different instead. "Like, if I got sick of geology, I wouldn't have to look at geology again for 10 years, right?" he laughs. "You can just go do something else."

This is why Dwarf Fortress development is so completely different to, say, your average triple-A or mobile game design. A regular game development team might spend months and years refining a title and polishing it up, making it "ready for market," and this is where Adams believes the enthusiasm can be lost.

"You explore new ideas in the interative development process, so it's not completely stagnant, but I can see how you can wear down a bit more," he notes. "With me, I was like 'Ohh -- I get to look up all the medieval garden crops now and learn all about plants!' I learned a lot about bananas recently. It's just wherever the mind takes you, you can explore. It's like getting tried of learning is where Dwarf Fortress is at now."

But Adams isn't convinced that he'll make the 20 year deadline, regardless of dwindling enthusiasm or not. Sitting at his computer day-in, day-out (or night-in, night-out, as the case may be) is taking its toll on the developer -- plus it's not like he's able to control how the world will work in the coming decades.

"I'm sure there's going to come a point obviously where we're kinda fading out, not really from disinterest, but just because our bodies are falling apart," he says. "And at that point, I don't know if the game is still going to be viable -- what operating systems are like, what weird headbands people are going to be wearing that let them see weird stuff with their iPhones -- and Dwarf Fortress could just be totally dead by then."

"Who knows how this stuff will work out," he adds. "But if we're still around, and we need to pass it on, then we'll probably think of some open-source solution that just gets passed along, and lets people do whatever the heck they want with it. We'll put up all our dev notes, etcetera. But that's just idle speculation, right? That's the general idea."

He sees the future life of Dwarf Fortress going the same way that the likes of Nethack or Dungeon Crawl have, with new devs teams picking them up and pushing them along.

"We've just had our mitts on this one for a long time without passing it along," he says, "but that's not going to be a forever thing, obviously. It's only going to stay afloat as long as people keep it afloat, right?"

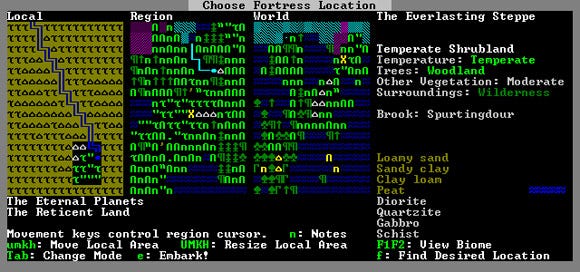

Dwarf Fortress was rather tricky to get into from the get-go, thanks to its ASCII art style and general lack of tutorials. But to an outsider looking in on this game so many years into development, with such a wide scope of features and potential play styles, it's fair to say that getting into Dwarf Fortress is perhaps one of the most daunting tasks the video game industry as a whole can provide.

"I think the game has actually gotten easier compared to what it was in 2006," Adams reasons. "It's not really the mechanics that matter so much, since a lot of the mechanics in DF are under the table. A lot of the updates don't matter either -- I mean, I spent a month on beekeeping, but you're not confronted with beekeeping, and you don't need to learn how to do it, but if you want to make wax crafts and honey, then it's an avenue you can explore."

The designer argues that there are different types of impenetrability, and that it all depends on what a player focuses on.

"There's the basic interface problems, such as not using consistent keys," he explains. "Then there's using graphics that aren't graphics, that kind of thing [laughs]. And those have gotten slightly better, rather than worse."

"But when it comes to things like indecision -- like not being goal-orientated, or requiring people to set their own goals -- I guess you could argue more features make that worse. Really, the fundamentals of staying alive haven't really changed much at all.

"So I think the more time that goes on, the better the Wiki is, the better the tutorials are, the more videos get put out, the larger and more helpful the community is. So I think it's probably easier to get into Dwarf Fortress now than it ever has been. Not that it is!"

When the game reaches the aforementioned version 1.0, Adams envisions tutorials, a more consistent interface, some context-sensitive help -- all these things are on his piece of paper, although he has no intention of including isometric, supported or packed-in tiles or 3D interfaces, given the great job that the Dwarf Fortress community has done on the visual side of things already.

In fact, Adams has already attempted to start work on tutorials for the game, but has found that this is an element of design that can really impede development progress.

"We talk about the graphics slowing down development, and it's one of the main reasons why we don't have them," he says. "Tutorials are sort of the same way, in that they are an anchor that you need to keep updated. But that's definitely a sacrifice that I'm willing to make, just because I think they would make a big difference just to get people started."

For now, he's happy to let the Dwarf Fortress community do the job for him. "There's a lot of people dedicated to helping others get into the game now, and if I were to become one of them, that would be even better," he laughs, adding, "I'm not laughing at people's pain -- it is hard, and it is all my fault. It's just when you've been talking about something for years, you start to get flippant, sometimes."

I asked Adams whether he believes it would be possible to build a game with the insane depth of Dwarf Fortress, that would feel more accessible to the average gamer.

"Surely," he answers. "It would be about delivering depth quickly. I mean, think of something like The Sims -- how many copies did that sell, right? That's not an uncomplicated game, and yet it's still played by millions of people. The Sims is a really good example of a game that is complicated yet accessible."

"And I mean, I've never played Minecraft, but I assume there's some depth to the game, if you wanna have it, right?" he adds. "Yet the base game itself is playable by an eight year old. So I think it's already here."

It's a godsend for the Adams brothers that they have such a dedicated fanbase that is not only happy to keep playing the game and help newer players out, but also donate tens of thousands of dollars simply to keep the brothers afloat. But what happens if, in the years to come, the player numbers begin to fall away and the income is no longer sustainable?

"I'll probably have to join that group of people who can't get a job," laughs Adams -- although he's well aware that that most likely wouldn't be the case. "I think we probably are at the point where if we started hyping a new project, people would pay attention."

"We could always trade in our reputation on a Kickstarter," he adds. "There's all kinds of choices these days, so it's not like I feel that I'd need to go and immediately do Dwarf Fortress part-time while I seek a job. There's alternatives. We'd still want to do Dwarf Fortress."

It's not really something that Adams likes to think about too often, given how incredibly depressing the thought is -- that people would just stop caring about your life's work.

"But it's also a foregone conclusion, right?" he says. "That's how these things always work. There are some things with staying power, like if you look at these roguelike games. But those communities are fractured a million times over. So who knows."

It helps the long-term reality of Dwarf Fortress that the game was recently chosen as one of the Museum of Modern Art's historial video games -- an event that really spurred Adams and his brother onwards.

"It made us feel like it's not like the floor is going to suddenly drop out behind us, even if support for the game dries out," he notes. "It also makes you feel like maybe support for the game won't dry out. It was a good milestone. And we've hit these milestones along the way, all of these things were stepping stones up to a feeling of confidence in our continued existence, and that's been nice."

Of course, there are methods by which the Adams brothers could potentially make their future more secure. One would be to get Dwarf Fortress on Steam, putting it front and center before millions of potentially new pairs of eyes. That process would involve going through Steam Greenlight.

"It's things like Steam Greenlight that have made the world a little weirder for us," Adams reasons. "Our policy is like well, it's like Field of Dreams, the Kevin Costner movie -- if you build it, they will come. Everything has been coming to us, all the press -- we've never placed an advertisement, never gone to a conference, or expo, or whatever."

Adams notes that he's not trying to make himself out to be selfish or arrogant -- it's simply that he didn't care about getting publicity when he first started developing the game, so when the hits began to roll in, he just sort of accepted what was happening.

This is where he isn't too sure whether Greenlight would be a good idea for Dwarf Fortress. "When you have things like Steam Greenlight -- I don't know if it's to that point where we're like, is this a low-hanging fruit that you should just reach out and say 'Okay, we'll be distributed on Steam,'" he says.

"I don't know enough about it, and it's the kind of thing that, from the years of inertia, we don't have these business instincts that kick in and say, 'Yes, we need to get on that.' So it's sort of the thing where, if enough people bug us because they want Steam to track their user hours or whatever... if our current fan base wants it on there, it'd be more of the kind of thing we'd be interested in, rather than increasing our audience."

So getting Dwarf Fortress on Steam would be more of a fan service move than one aimed at pulling in new players?

"I guess so, yeah," he answers. "I don't know if I sound incredibly selfish when I say that, because people work to get their games put up on Steam and work really hard on getting people to see their games. I wouldn't say we got that stuff for free, because there was a lot of work put into the game to get it to the point where people would start talking about it. But now that I'm not concerned about that, I just don't know if it's a total waste, or whatever."

While the topic of getting the game out to more people is up in the air, I ask Adams whether he has considered porting the game to other platforms, such as mobile or the PS Vita.

Mobile hasn't really been a possibility up to now, since Dwarf Fortress is a pretty intense game CPU-wise -- even ignoring the potential interface problems, mobile devices simply haven't been powerful enough to keep up with the vast number of calculations that the game is constantly doing. However, Adams acknowledges that "the specs are starting to get into line," so the possibility of Dwarf Fortress on a tablet is definitely closer to reality now.

As for PS Vita, he notes that "if someone approached us, we're not giving the code to anybody for any reason, so it would have to be something we could compile ourselves."

"It would also need to make sense to put it on the Vita," he adds. "Right now I've got a process that I do myself, where I compile it on Windows, compile it on Linux, and compile it on the Mac manually over here. The guy that ported it had to go through a pretty hellish process of my not giving him the full source code. He didn't get it, despite working with me for years, and basically having my complete trust. I mean, one mistake and we're in a lot of trouble with the code being out there."

Potentially signing an NDA to counter this possibility wouldn't matter to Adams. "I need to have a way to compile it, and I just have no idea how that works on [other] platforms," he adds. "I guess you download these developer SDKs. If Sony was willing to bear with me through that kind of nonsense, which I don't think they would be, to get one more game... it would take that kind of dedication. Which is why it usually comes from fans who care, and people who are willing to volunteer and go through the nightmare with me."

"So we're not against other systems, but it has to fit into the pipeline we've got, because of our restrictions," he says.

It's obvious that at this point in Dwarf Fortress' development, Adams and his brother must have received plenty of offers from publishers -- both to publish the game, and to offer the duo jobs. Adams tells me while he would never consider working for someone else ("we want to work on our own stuff, and the money doesn't matter"), he has considered signing Dwarf Fortress up with a publisher before.

"There was an offer to use the Dwarf Fortress name - sort of 'Dwarf Fortress: Subtitle' or whatever -- they wanted to brand one of their other games," he tells me. "And the amount of money on the table was six figures."

He adds, "When you look at that you think well, there's trade-offs. Does the brand get cheapened? Are you deceiving people? As long as they're clear this is not Dwarf Fortress or whatever, and this is not Dwarf Fortress with graphics, as people call a lot of things that are coming out these days. As long as you're upfront and honest, there's not technically a problem with that -- it's our brand to piss all over if we want."

Signing up with a publisher or giving Dwarf Fortress rights to another developer wouldn't necessarily be bad for the current fans either, he reasons. "I mean, if we had enough money suddenly to become independently wealthy and not worry about our health insurance anymore, then we're working on Dwarf Fortress even more than before -- who should complain about that?"

He muses, "It would take a very philosophical person interested in way down in the details of ethical behavior, I think, to find points of concern there. I mean, I wouldn't necessarily disagree with that person. But we've certainly talked about it, and considered some ramifications of that."

Those ramifications are what has held the Adams brothers back from such a deal -- namely, the pair believes that they were actually end up losing money in such a deal, rather than making more.

"If people saw that there was this other thing out there, we considered in the worst case scenario, then the contributions from people would just dry up, and we'd be sitting with this lump sum that would not have added up to 10 years' salary or whatever. So do we want the stress of having to search for a new IP, or a new angle all of a sudden? We have some name recognition to be able to do that kind of thing perhaps, although it's a very chancy thing."

Of course, the flipside is that it's not like Dwarf Fortress isn't risky enough as it is -- as Adams notes, "putting all your eggs in one basket like we have is a very chancy thing, right? I mean, it just takes a superior game to blow it all out of the water. There are no rules when it comes to copyright, or whatever."

With Adams touching on the idea of another similar game taking Dwarf Fortress to town, I asked him why he thinks no one has managed to successfully clone the game yet. There have been plenty of notable games inspired by Dwarf Fortress, of course, but none that really copied both the depth and the visual style of the title.

Adams believes that one of the main reasons his game has held its own is that other developers who are keen to create a similar product realize very quickly just as much of an undertaking it will be.

"We can't really know whether they were discouraged at the size of the undertaking, or whether it was never their intention to begin with," he adds of projects like Town, Dwarves?, and Game of Dwarves.

"Things like Clockwork Empires coming up are more ambitious. It seems to be doing a bunch of stuff, that'll be an interesting one to watch. But I'm just not sure if there's a point to emulating Dwarf Fortress completely, because it's not like we're a big market. It's not like people see our $50,000 a year and think 'Hey, I want a piece of that pie.' They'd much rather look towards things like Minecraft, where there are hundreds of millions of dollars."

On the topic of Minecraft, Adams is hugely grateful whenever Markus Persson and co. says that the game is inspired by Dwarf Fortress -- "that's probably where half of our fans come from!" he laughs.

Going back to potential cloning, or perhaps even a Dwarf Fortress-like game that does the job better, Adams says it's bound to happen sooner or later.

"We're happy we've managed to stay afloat for so long," he says. "I'm surprised that we haven't had our wings clipped by somebody. It just hasn't happened yet."

"I was reading on Gamasutra about 'Is free-to-play ethical?' and all that kind of thing, talking about monetization and Skinner Boxes," Adams tells me. "We're very fortunate that we've escaped from having those concerns, and managed to make a living somehow."

Indeed, the way in which Dwarf Fortress is funded -- a completely free game that survives via donations from players -- is a far cry from the various business models that are carted around in the modern video game industry.

Adams reckons he knows exactly why his business model works for him, but wouldn't work for many others.

"We're not searching for a million-dollar hit, which is the feeling I get from other people -- what they are searching for when they release on iPhone and so on," he notes. "That's not everybody, of course. But we don't have to work that hard anymore, thinking about exactly how we're going to monetize."

"I've seen what people go through," he continues. "Rocketcat Games (Punch Quest) lives out here, and we meet up with him sometimes. And it's just a struggle, right? To decide how you wanna set up your free-to-play model. His was, what, too generous? So it didn't work out. Those kind of decisions, we've been very fortunate to have enough wiggle-room to bobble the ball completely, which is what we're doing."

Those who have followed the Dwarf Fortress story will know that Adams sends out crayon drawings to people who donate money, and adds them to a "Champions' List" -- a rather different proposition to what game developers offer nowadays.

"I mean, that's just completely weird, right?" he laughs. "But fortunately we don't have high demands, we don't need a lot of money, and we're making just enough to tread water. $50,000 for two people a year."

"I guess it's like shareware," he says of his own monetization technique. "We didn't really take inspiration from anything. Someone said to us, 'Why don't you put up a PayPal button for your birthday so I can send you $50?' And then over the next four or five months, we made around $300. I was still working then, and Dwarf Fortress wasn't even out. Then we released the game, and started making $800, $1000 in the subsequent months. And we were like, 'Maybe we actually have a shot.' Now we're averaging $4000 a month, baseline, which is crazy."

With Dwarf Fortress making $50,000 a year from donations alone, I questioned what sort of spread of donations Adams received. I'd assumed (correctly, as it turned out) that it isn't simply a bunch of people paying small amounts, but rather, Dwarf Fortress has its own "whales" -- people paying silly, unnecessary amounts.

"There's a subscriber system now, just because people asked for it," he tells me. "There's people who have given four-figure amounts. But these are not people who we necessarily haven't talked to before -- all of them send in their regards ahead of time, and they all know exactly what they're getting, because they've all been playing the game for ages -- years, in some cases -- before they send anything. They're not getting any sort of compensation for it besides some sort of story."

"I guess there are lots of parallels to be drawn between the whale system," he continues, "but there are people who give recurring money and large amounts. Some people have donated computers. Some people have donated their time -- there's a lot of volunteers handling the bug tracker and answering questions for people. There's the guy who did the port for Mac and Linux -- that was all free."

Everyone just wants to see Dwarf Fortress development continue, he reasons, so if they like the game, it's in their best interest to throw some money his way.

"I guess you could say the whale has an interest in receiving their present," he adds. "It's obviously a spectrum of giving -- a spectrum of ethical behavior. I don't know enough about what goes on in other markets to pass judgment offhand, but I know people talk about that."

While the Adams brothers are very clearly indie developers, it's notable that the pair rarely converses with other indie devs, or gets involved with the "indie scene" at all.

"It's not a deliberate thing," Adams tells me. "It's part of a personality thing, if anything. I didn't have many friends growing up, and didn't feel the need to hang out with anybody. So with Dwarf Fortress, I don't really see the upside. I've never really been a Twitter/Facebook kind of guy. I mean, it's fun to watch people talk to each other, but it's never the sort of conversation I would participate in."

That's not to say that the brothers don't ever participate. As previously mentioned, they've met up with Rocketcat Games and sampled a wide variety of mobile games that they wouldn't ordinarily have tried. Plus, the pair went to the EVE Fanfest earlier this year in Iceland, with Adams as a speaker -- "we accepted it because, you know, it was cool!"

But in general, Adams isn't so keen on socializing with other devs. "Things like GDC to us, were not a place we were invited to go," he says. "It was a place that you paid to go. And all the expos too. And networking never made sense to us, because of the nature of our situation."

"It's not like we're going to look for a job if this doesn't pan out -- we're not going to go and work for another studio or something," he continues. "We're just not interested in doing that. So there just hasn't been a need for it, even though I'm sure we'd benefit from it a lot. We don't feel like talking about the craft of game design or whatever. We kind of have a mature process, I guess, since we've been doing it for 13 years."

Although Adams has a PhD in mathematics from Stanford University, and taught mathematics for a short while, he says that his lack of drive to socialize stunted his mathematics PhD work somewhat. As he points out, mathematics is a very social field, at times.

"As much as you imagine people in closets working out theorems in the dark or whatever, it's all about co-authoring papers and not stepping on each other's toes, and working together on things because it's so complicated," he says. "I'm just not a socially-constituted person, I guess."

But despite his lack of social skills and his hiding himself away while he works on the game of his life, Adams is perfectly happy with where he is, and how the future is looking.

"I'm really satisfied with how things have turned out," he explains. "Having spent 13 years, you can kind of talk about 20 years without seeming like a total prat [laughs]. But we fully recognize that when you're talking about two decades in the future, who knows what the heck's going to be going on, right? Anything could happen. We'll be entering the age of health problems. Economic this and that."

"But I feel more at ease," he adds. It was something I never felt in mathematics when I was working on that stuff. I never reached a milestone like that. But who knows what's going to happen next."

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like