Featured Blog | This community-written post highlights the best of what the game industry has to offer. Read more like it on the Game Developer Blogs.

Double-Fined: Selling Overhead to Fans

"I do know that as long as players are willing to pay for overhead like they have been so far, the industry will find new and creative ways of selling it to them – and even elicit heartfelt, teary-eyed thanks in the process, because Stockholm Syndrome."

(Note: This article was originally posted on http://odiousrepeater.wordpress.com. I'm reposting it here in part because of this news article on Mighty No. 9's second crowd-funding drive.)

---

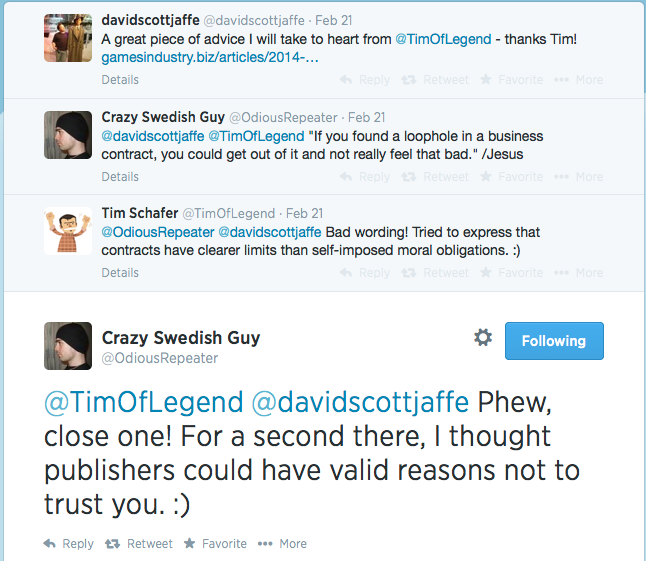

A few days ago, the following good-natured exchange happened on Twitter between myself, David Jaffe (Twisted Metal etc.) and Tim Schafer (Grim Fandango etc.):

[Full disclosure: that was the end of the conversation. Must've been something I said.]

I recommend reading the article linked to in the David Jaffe’s original tweet, it’s quite good. But for the sake of what I’m about to write in this post, the Twitter exchange should be sufficient.

Actually, it’s not really the contents of the back-and-forth in itself that’s interesting. We have the original text, and we have Tim Schafer’s clarification in < 140 characters. Whether you believe him or think he’s just whitewashing a gaffe is up to you. His real attitude toward his work, his fans, publishers and the industry at large is probably only truly known to him, and I’m not interested in pretending to know his intentions. I’m more interested in knowing what you, the readers think – and how that will influence your actions.

Let’s take Tim’s original statements at face value for a second. Let’s say that development agreements with publishers are completely cold, calculated business endeavors. The only bad thing that can happen is that they stop funding the project and/or sue the developer, and that’s the only thing the developer needs to care about. Ethics or morals don’t factor into it; even if you are interacting with people on the publisher side, they are just cogs in the machine and don’t really need to be respected as stakeholders or even human beings. They are there to fund Tim Schafer [or Ken Levine or Warren Spector or Shigeru Miyamoto – I’m not calling anyone out in particular] games, and passive, silent partnership is the only thing their financial sponsorship buys them.

That’s not all Tim’s saying though. He’s also making it clear that being crowdfunded – getting money directly from his fans – has put him in a position of having made a moral contract with players. And that the fulfillment of that moral contract is about making people happy. “But here, if the backers were happy, we succeeded. And if they weren't happy, we didn't”, he is quoted as saying.

So with all of this established, I would like to ask you, dear reader, something important:

What do you think?

Are you leaning more towards believing what Tim says or not believing it? Most importantly, do you think he feels more obliged to deliver on his promises for a crowdfunded project than a publisher-funded one?

Now, the reason I asked that you consider your initial gut reaction at first is because I want to add a bit more nuance to the thought-exercise once you’d done that. So now let’s step back and consider the following questions:

For as long as Tim has been working with publishers, how many of them do you think he told, to their faces, “we have no moral or ethical obligation towards you, and if we find a loophole in the contract then we can use it and not feel so bad”?

If “keeping backers happy” leads to “success” that is in some way analogous to the success one would have in a developer-publisher relationship, how can one quantify such success? (Hint: MONEY)

If a developer wants to finance their game through crowdfunding, which phase of development is the most important?

Assuming that the fans who are crowdfunding the game have little to no understanding of game development, does that incentivize the developer to be more or less transparent than they would toward a publisher?

In light of your answer to the last point, what do you think the purpose is of development diaries and similar means of “updating” people on the game’s progress? And can you think of any reason why one would restrict access to such materials to backers only?

What’s the worst that can happen to you and/or your company if you fail to deliver on your promises after the pledged money has traded hands?

If you agree that the company’s reputation, or indeed the Auteur front figure’s reputation, becomes the most important commodity in trying to secure future funding, how should you handle public-facing interviews?

Is there any simple way to mitigate failures to deliver? Can it be glossed over? Whitewashed? And if you do decide to bullshit your backers, what level of bullshittery are they capable of seeing through? Is it a higher or a lower level than a publisher would accept? And with that said, what is the average net loss of goodwill that would result from failing to deliver, but then mitigating it, for example by doing interviews like the one we began by quoting? What does it equate to in actual money pledged to future projects, if one were to make an educated guess?

Now, if you’ve made a sincere and honest effort to think all of these questions through, let’s revisit the original one again: are you leaning toward believing Tim or not when he claims to feel responsible for your being happy with his work? Do you think that he and his team, or indeed developers in general, respect you?

If the answer to that last one is “yes”, then at least some small part of the industry has done its job. Because these days it seems more lucrative than ever to pretend to take players seriously while in fact not giving a crap.

Funnily, this image made the rounds as I was writing this post:

… and it’s quite poignant. But if we allow ourselves to set aside wit and brevity for a moment, we can add a bit more nuance to our picture of what games are these days. Thing is, there have always been different business models, some stingier than others, and the perceived value for money has always varied massively. Someone complaining about Free-to-Play these days should remember the days of arcade machines and what a minute of sustained play time could cost back then. Over time it became increasingly difficult to justify such prices, to a large degree because of the improvements seen on the home console front – but that’s the whole point. Companies have always tried to find different ways to compete with each other for customers’ hard-earned time and money. What’s been happening recently, however, represents a paradigm shift in what the customers are being sold: overhead.

For those who might not know, here’s one common definition of the word: “The term overhead is usually used when grouping expenses that are necessary to the continued functioning of the business but cannot be immediately associated with the products or services being offered (i.e., do not directly generate profits).” [Wikipedia article]

Now don’t get me wrong; there’s always a degree of overhead involved in any product you buy. But certain developers have recently found ways to commodify (verb: “to turn into a commodity”, I just made it up) their overhead. Kind of like when butchers figured out that the kind of meat that was unfit for human consumption could still be sold as animal feed. Or maybe ground up into sausages.

The point is that there are now plenty of opportunities for an end user to not only buy into games that have yet to be finished, but to purchase the stuff that would otherwise end up on the cutting room floor. Sticking with Tim Schafer and Double Fine studios, their Amnesia Fortnight fundraisers provide a great example of what I’m talking about. For Amnesia Fortnight, the Double Fine developers split up into a bunch of teams and then proceed to build small game prototypes that the players can then pay to access. Basically, they are selling their in-house prototyping sessions to end users. In fairness, the player can influence both the sum of the donation and how much of it goes to charity – but the idea is still to monetize an exercise that otherwise would have just been considered overhead. Now, is this intrinsically a bad thing? No, absolutely not – if it’s done in earnest and players are informed of what they are getting for their contributions. I’m not approaching this from a moralizing standpoint (though it might make sense to remember the bullet points from earlier in this case also – what’s the angle here?). I am, above all, trying to illustrate a trend.

Another example can be found in the splitting up of Metal Gear Solid V into two separate products. Now, there’s been a lot written about the amount of content available in the “prequel”, called “Ground Zeroes”, and the artistic considerations at the root of those decisions. And sure, I don’t really know what’s going on, not to the extent where I can prove it. But… who are we kidding? Does anyone think that it’s not a money-making exercise? Everything from the statements made by Kojima to the length of the game's main story to the “open world” nature of it makes it obvious to me that Ground Zeroes is Konami’s way of monetizing Metal Gear Solid V’s pre-production phase, including the expensive Fox Engine. As an added bonus they will get sales and metrics data that they can use to influence the content and feature design of the actual Metal Gear Solid V: The Phantom Pain.

One way of looking at is that they are taking the full game + DLC model that we’ve gotten used to and turning it on its head. And why wouldn’t they do that? I mean, think about it: the standard model relies on you shoveling loads of people in at one end, and those that like the game for its story (if it’s something like The Last of Us) or emergent gameplay (in something like Battlefield) or whatever else will want to buy the new stuff that you release for the game, post-launch. The problem there is that you’re monetizing an increasingly hardcore fan base. On the one hand the player base is getting smaller and smaller as time goes by, which means that you’re supposed to be making the cost of each DLC pack back from an ever-shrinking group of players, even if the development cost of each DLC pack may be static. Another problem is that the player you will milk for the longest length of time are your staunchest fans, and you should take care not to piss them off and have them lose patience with you.

In light of this, the Metal Gear Solid V model is absolutely brilliant. You mitigate any backlash from the hardcore fans by calling it a “prologue”, and pretending that the reason you are doing it is to throw them a bone before the full game arrives. Then you charge something like €30 for it which isn’t as much as a full game, admittedly. But when you consider that Ground Zeroes was originally meant to be part of the Metal Gear Solid V experience and only later excised, it becomes obvious that you’ll be paying for at least the engine + the majority of the features twice. Indeed, I expect quite a bit of content to reappear in The Phantom Pain once that’s released. But what unique content you may find in the game (probably not all that much, considering how Kojima said that the game wouldn’t feature lengthy cutscenes because they were “outdated”, which sounds like a whitewash to me) is most likely there just to gloss over the fact that you are essentially being asked to pay for what would otherwise have sufficed as a demo in years past. Oh, and the “open world” structure is really convenient in that regard too. It makes it easy to add loads of padded, modular content to the game world for relatively little, and obfuscate the fact that you’ll end up up paying about €90 for the full Metal Gear Solid V experience. Yes, buying games at launch + all the DLC can also end up in that same price range, but that’s not really the point. The point is that instead of making the core game good so that they can sell the higher-markup DLC to still-hungry fans later, Konami has flipped the value proposition on its head, to make as much money off of as many people as possible for the smallest amount of investment possible. Sell the Vertical Slice, profit, and then sell it again as part of the actual game. As a bonus, you’ll lower the barrier to entry for all those people who may not be fans of the franchise already, but who wouldn’t mind paying a small sum just to see what the fuss is all about. It's kind of like focusing on appetizers rather than desserts. And also deriving the appetizers from the main course. Genius.

Finally, there’s Steam Early Access (and, I suppose, similar programs if they exist), where players are allowed to volunteer, and in some cases pay to volunteer work on a game that they find interesting. This may be one of the sneakiest ways of having people pay for your overhead, in that players really do get access to a playable (well, executable) game. Thing is though, just as with Kickstarter:ed projects, this model bypasses all fail-safes you’d have if you were a publisher rather than a consumer. But it’s even worse than that. Because not only are you handing over a no-strings-attached investment to the developer, you are probably happily investing your time and energy too (and they probably even managed to make you feel privileged in the process). So you’re not only paying for their overhead with money, but with your sweat, patience and (hopefully) innocence and naïveté too.

It’s said that the more things change, the more they stay the same. That’s as true here as anywhere else. All of this is just a continuation of the same root policy as always: try to get the biggest possible return on investment. Even trying to sell different modules off is nothing new. Developers have been licensing middleware and whole game engines since basically forever.

So the big paradigm shift here isn’t really so much on the supply side of things, as they – we – have always been willing to do something like this. In a sense, making sequel after sequel is another way of accomplishing a similar thing; the first installment in a franchise is usually the one with most of the overhead, and hence the one you sell at a relative loss that you expect to recoup with low-risk “content sequels”. No, the big shift is on the demand side, and to some extent in the technology we use to reach the players (in the cartridge days splitting a game up in fractions like those of Metal Gear Solid V would’ve been unthinkable). I’m not sure exactly how we ended up here, and I’m in no mood to retrace every step. But I do know that as long as players are willing to pay for overhead like they have been so far, the industry will find new and creative ways of selling it to them – and even elicit heartfelt, teary-eyed thanks in the process, because Stockholm Syndrome. And if overhead is ultimately the only thing that players end up paying for, if the product itself doesn’t materialize in its polished, shelf-worthy and most importantly promised form, well... I suppose that’s when we’ll see if any developer truly thinks that fulfillment of the “moral contract”, as an incentive to deliver on one’s promise, is even remotely comparable to the threat of a lawsuit.

What do you think?

Read more about:

Featured BlogsAbout the Author(s)

You May Also Like