Devs share real talk about surviving the latest 'indiepocalypse'

Indie devs from across the industry took the stage at GDC’s Independent Games Summit today to give their own answers to a simple question: what do we mean when we talk about the 'indiepocalypse'?

For many developers, last year was underscored by talk of an ongoing indiepocalypse. But that's a scary, unspecific buzzword -- what does it actually mean, for working game devs?

Indie game makers from across the industry took the stage at GDC’s Independent Games Summit today to give their own answers to that question.

“One thing we all agree on is..this word is super-crappy,” said Tiger Style’s Randy Smith, to open the talk. “It’s reductionist.”

Smith noted that many developers have heard horror stories of market overcrowding causing good games to go unnoticed (and unsold), stories that are still being shared here at GDC this week.

“We have some numbers that estimate the size of the indie games market,” said Smith, citing fresh stats provided by SteamSpy (and subject to the caveats that come with SteamSpy’s data.) “Valve [now] processes significant more than $1 billion in indie game sales every year, and it’s over one third of their total game market.”

Smith went on to show how free-to-play games outpaced premium games on the App Store around 2011, and have grown that lead since. However, he also reminds fellow indie devs that stats can be manipulated to suit arguments, and that what matters, in the end, is how each indie developer cuts their own path through a challenging market.

To share his story, longtime indie developer Jeff Vogel took the stage to talk about how Spiderweb Software (Avernum, Geneforge) have survived.

"Success should always surprise you; failure should never surprise you"

“I don’t make hits,” said Vogel. “I’m in the business of making respectable middle-class titles to make a respectable middle-class income.”

For Vogel, the "indiepocalypse" is a misnomer. “It’s basically inaccurate; there is no apocalypse. Indie games are awesome, people love to play them, they love what we do, so people will keep making them.”

Vogel recounted a quick summary of the not-at-all apocalyptic (but still problematic) way the indie business has changed in the last few years. Indie games became much more profitable around 2008 thanks to the launch of services like the Xbox Live and Steam, and the growing democratization of game tools. That led to a boom, then a bust, then a recession -- something Vogel compared to a very standard, predictable business cycle, though he admitted that making games is harder to quantify than making staplers.

“It’s hard to do research on this topic,” admitted Vogel. “It’s like comparing apples to oranges.”

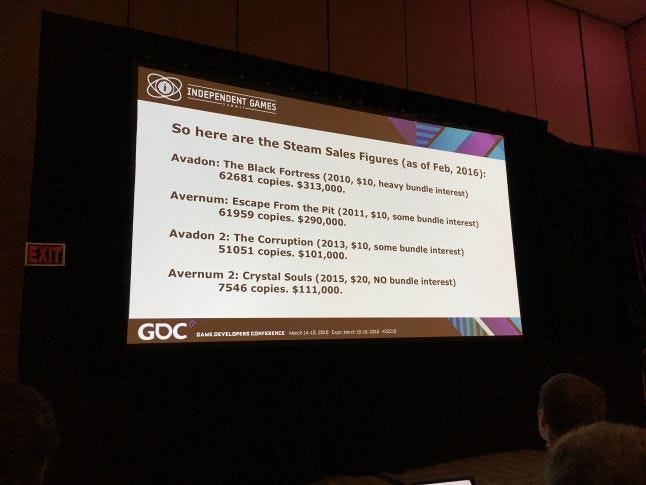

So he did his best by comparing sales of his own games through time, since he notes Spiderweb’s games tend to be very similar and thus cater to the same audience.

With the caveat that the "copies sold" numbers include sales outside of Steam (usually keys included in bundles) but the earnings numbers only include Steam, Vogel noted that Spiderweb’s Avadon: The Back Fortress, relased in 2010, sold 62,681 copies and brought in $313,000 to date. 2015’s Avernum 2: Crystal Souls sold 7,546 copies and brought in $111,000.

“The games business is hard,” said Vogel, who’s been making games since at least the ‘90s. It’s always been hard, in his estimation, and right now we’re just going through a predictably tough period.

“Success should always surprise you; failure should never surprise you,” said Vogel. “That’s the cost of following your dreams.”

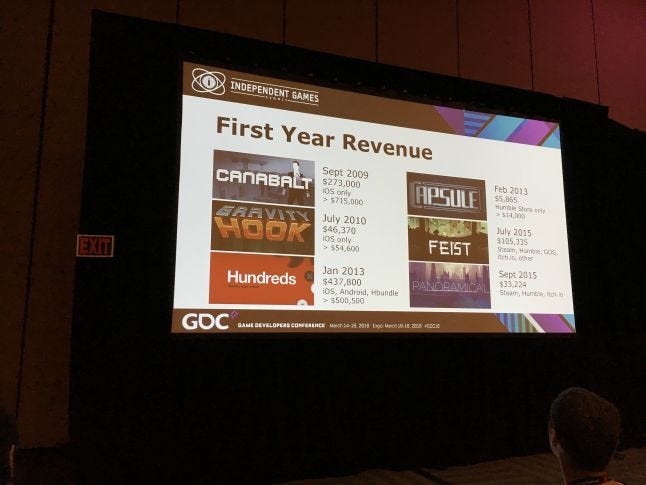

To keep the stats-sharing train going, Finji chief and cofounder Rebekah Saltsman took the stage to share some sales numbers for games in Finji’s catalog, noting that the majority of Finji’s income comes from Steam (for PC games) and iOS (on mobile).

"We're streamer-friendly now"

She went on to advise fellow indie devs that, even after making games for years, Finji has a tough time predicting what games will do well, and how well they’ll do. Hundreds, for example, had incredible first-year sales and an equally incredible drop-off shortly thereafter.

First-year revenue is the first number alongside every game, total revenue to date is listed beneath it

“We expected a long tail after a high launch, and it dropped off significantly after 14 months,” said Saltsman. “There was a race to the bottom; people didn’t want to pay that much for games.”

Layer that atop the fact that its production time ran long, and Saltsman says it didn’t actually make enough to fund Finji’s next project despite its seemingly huge success.

If you can pick it out in the slide (badly) photographed above, you can see that Finji's recently-released music visualizer game Panoramical also had a rough launch, and Saltsman notes it was for a few reasons: Finji didn’t grasp the importance of streamers for driving sales, for example, and they couldn’t find the right words to talk cogently about what the game IS to the public.

“We’re streamer-friendly now,” said Saltsman. For example, one of the studio’s current projects, Overland, has thus been explicitly designed to be streamed and to be as replayable as possible. The studio also makes a point of reaching out to The Internet to talk about the project, and to talk about life in general.

“We think project vulnerability is an asset,” said Saltsman, noting that the studio finds it valuable to push its staff to not censor themselves online. “We talk about our funding problems, we talk about our kids...we’re real people.”

"As a developer, you get pissed off"

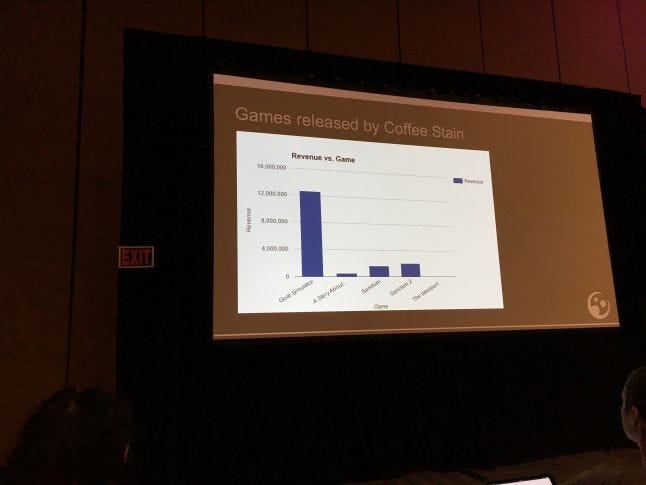

Coffee Stain Studio’s Armin Ibrisagic noted that the studio was already seeing discoverability issues between releasing Sanctum and Sanctum 2 in 2011 and 2013, respectively. He even noticed people on the Internet talking about how they’d enjoyed Sanctum and put dozens of hours into it, so they just couldn’t wait to pick up Sanctum 2 -- for a song, during a Steam Sale.

“As a developer, you get pissed off,” said Ibrisagic. “Is there a competition I don’t know about, to try and give as litte money as possible to the developers you love?”

When the made Sanctum 2, Ibrisagic said Coffee Stain wanted to make “the coolest indie game we could make.” They focused on quality and quantity of content, trying to make the “most AAA” game they possibly could.

By contrast, the design philosophy of Coffee Stain’s more well-known project, Goat Simulator, was simply to make something..weird.

“And well, you know what happened,” said Ibrisagic. Goat Simulator went on to more than triple the sales of the rest of Coffee Stain’s games combined. His big takeaway was that more content -- more levels, more characters, more “quality” -- doesn’t translate to more sales. What translates to sales is uniqueness.

Making a game that’s completely “crazy”, unique or different is a good idea, advises Ibrisagic, because it catches people’s attention and offers them something unlike anything they already have in their Steam backlog. They’re more likely to want to play it right now, and thus more likely to buy it right now.

The Magic Circle studio Question only has one indie title under its belt, so studio cofounder Jordan Thomas chose to try and solve the “murder mystery” of the game's underwhelming performance in lieu of having a lengthy history of indie game sales data to share.

"I'm just hoping that if we go through another one of these boom-bust cycles, we can pick a better name"

So what happened to The Magic Circle? “We sold about 16 and a half thousand copies, and we’re on about 44 thousand wishlists,” said Thomas, even after the game got better-than-expected preview coverage, good review scores, and an IGF award nomination. “This is unsustainable for us.”

So what did Question learn from the game’s underwhelming performance? Where did they go wrong?

“We had no marketing budget,” admitted Thomas “We focused on making a great game, and hoped the rest would self-align -- that was the wisdom of 2013.”

He also believes the games’ tongue-in-cheek lampooning of game development put a lot of reviewers off ("'this game is so ANGRY,'" quoted Thomas) and believes its lack of a clear genre actually hurt it in the market.

“We could have had a more clear genre for a debut title, “said thomas. “Steam players do respond well to your game being like….anything. [They like] some kind of touchstone!”

Thomas wanted fellow devs not to rely on Steam to make their fortune, and to keep alternate options in mind.

“The time we spent on The Magic Circle has claimed our innocence,” said Thomas. That might be healthy, but it still feels like kind of a loss right now.”

“Relying solely on Steam was our mistake,” said Thomas. Now, the studio is hoping to pick up more sales by bringing the game to console and is working on a newer, “safer” project that’s multiplayer-focused.

“All of this, we kind of went through this arleady,” said Thomas. “I’m just hoping that if we go through another one of these boom-bust cycles, we can pick a better name than ‘indiepocalypse.’”

"We got everything we wanted, the list of stuff we talked about in the '90s"

Tiger Style's Randy Smith hopped up on stage to close out the conversation (for now) by explaining how he believes the indie game market has become a treacherous place to try and launch sequels -- most notably, Tiger Style's recent sequel Spider: Rite of the Shrouded Moon.

“We had every reason to believe Spider 2 was a better commercial project than Spider 1,” said Smith. It was launching on multiple platforms, instead of just mobile, and "we did a bunch of the things indies do when they’re promoting a game.”

The two games reviewed about the same, as generally good games, and Spider 2 had “tons more content and lots more features” than Spider 2. New concepts, new features, new levels….

“Despite that, Spider 2 did all the work but Spider 1 got all the glory,” said Smith. “Obviously Spider 2 is a better product,” but Smith believes Spider: Rite of the Shrouded Moon suffered for being multiplatform; he believes the game didn’t get as much promotion from Apple because of that, and recommends that fellow developers target a specific platform to have the best chance of cutting through the crowd and reaching an audience.

“This is an audience that’s interested in cool, new things” said Smith. “Even if your design and art is objectively better than your prior game, which earned a game of the year award, that attention is being focused on fresh new games.”

Smith believes the current indie market likes unique, high-concept games -- like Downwell, or Goat Simulator.

Those are good examples of small “indiepocalypse-retardant games”, games which are, according to Smith, either very big (in terms of scope and budget) or very small. If your game is sort of medium -- like, say, a polished, expanded, expensive sequel to a breakout indie hit -- it’s probably going to flounder in today’s market.

Console ports are also a good idea, in Smith’s eyes -- but not on launch day, when it could distract or complicate the lauch. Instead, Smith advises that indie devs consider launching their games on Steam and porting them to consoles later to pick up new audiences (and sales) -- much like Question is doing with The Magic Circle.

Still, the veteran game maker tried to close out the discussion on a positive note.

“I’m old enough to remember what it was like to make games in the '90s, and it was fucking awful,” said Smith. “We got everything we wanted, the list of stuff we talked about in the ‘90s; now we just have a much bigger marketplace filled with creative people. I think that’s a good thing; I’m happy to have them here.”

"I hope every single one of you moves to VR," added Vogel later, in response to a question about whether indie devs should get into VR while the getting's good. "'Cuz then, more candy for Jeff!"

Read more about:

event gdcAbout the Author(s)

You May Also Like

.jpeg?width=700&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)