Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Demiurge Studios has gained a reputation as a reliable developer doing work-for-hire for larger studios like BioWare and Harmonix, but now the company has plans to break out -- studio director Albert Reed explains how it reached that juncture.

Demiurge Studios has, in recent years, gained something of fame as being a reliable studio -- for working on other studios' properties, an odd position to be in as work-for-hire doesn't usually get you any notice. Bin this case, the fame may be hard-won, but it's unclear what it says about the studio as a creative force.

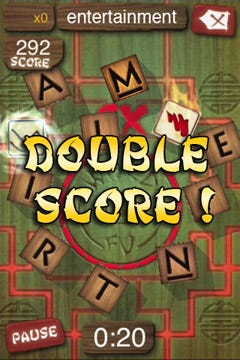

Over the last few years, the studio has developed the PC version of BioWare's Mass Effect, worked on Borderlands with Gearbox, and most recently completed development on Green Day Rock Band for Harmonix and MTV Games. The only original title the studio has released in the last few years was WordFu for the iPhone, which was published by ngmoco.

However, Albert Reed, the company's studio director, hopes to see that change very soon. The studio is set to debut an original title in the near future -- and while Reed wasn't quite ready to talk specifics, just yet, he spoke in great depth about why it's taken the team so long to put together an original project.

His insights on process and pragmatism run against the grain of much of what you hear about behind-the-scenes decision-making at studios.

I'm familiar with the titles you've worked on in the past, primarily working with other studios on existing properties, but it sounds like you're ready to move forward with your own stuff.

Albert Reed: Yeah. Over the past eight years of being in business, I think we've always had our eyes on working on big licenses, because it's super rewarding and we have a lot to learn from the other great developers we've had the chance to work with... but we want to pair that business with original property development as well, sort of mixing big-risk, big-reward in original property versus the safer shores of licenses. It nicely stabilizes the business.

How have you navigated those waters? Some studios find it a struggle to keep things going while working on licenses -- to keep their reputation, to keep getting work.

AR: I think we've chosen our projects really carefully, right? We have always tried to sign up for titles where quality will have an impact on sales, so basically where our work ends up mattering, and the quality of the work ends up mattering.

That helps our employees be proud of the work they generate, rather than thinking that they're working on something that you have to get on store shelves and get it to sell. If you look at the licenses we've tried to work on, they have been products where quality is the hallmark of the brand.

How did you establish your reputation and get involved in projects that are a cut above?

AR: From the very beginning, we tried to work with companies that we looked up to. Epic Games gave us our break many years ago, and from there, we started at a pretty high level, and if you deliver on the work, then the other studios that play at that level start asking you to help out with their projects. That's how we ended up working with Gearbox, Harmonix, and BioWare.

Green Day Rock Band

With all these projects, you haven't had a shortage of stuff to work on, but how did you find the time to develop something internally, knowing that you're going to have to cover the costs -- I'm presuming -- of the initial stages, at least, of that effort?

AR: One of the benefits of working on those higher-end licenses is that the people you're working with know you have to spend money to make money, and when we are working on that caliber of titles, we are able to charge a premium for the work that we do.

And we're very frugal. I'm known around the office for being downright cheap, and we save our pennies. The founders and the owners have never been interested in taking money out of the company; we're in it to build a studio we want to work at forever, so that's been our focus.

You're not going to talk about the details of the title just yet, but looking out at the market, how did you decide this was the right time for you to start really pushing forward with this project?

AR: I don't think the market forces were the driver. I think it was the studio becoming mature enough to be able to do it, and having the financial wherewithal to do it.

We certainly have been, as we began the path of IP creation -- which has been a learning experience to say the least -- we looked very closely at what's playing well in the market and where we think things are going to be in two years, and what's going to be popular and what's going to be cool, and trying to dissect that, looking for vacancies that we think won't be filled in the next couple of years, and designing our products around that for sure.

I think more than anything else, it's the right time for the studio more than it's the right time for the marketplace, and we'll build a product that is then well-timed in the marketplace.

Speaking of your upcoming game, you said now is about when you guys realized that the time had come, from a studio perspective. How did you develop that self-awareness and control over your destiny, rather than saying, "Let's just take a chance! We'll pitch people"?

AR: Well, we did pitch people. We've done that, for sure, before. We take some idea we have.

Our first pitch, year one, I swear to God, the name of the game was Hubris. I think the other people who worked at Demiurge realized the irony in that, but it was just lost on me.

It's been something we've always wanted to do; the difference is, then, we had a sort of doe-eyed ignorance. It's almost good that we didn't get that gig, we didn't land that project, because we probably would have flubbed it in the end -- because you don't really get second chances in the game industry.

We started thinking about the right size for a project for a studio of our size, and our shape, and our experience. In addition to picking original properties, and thinking about the marketplace also, thinking about what was right for our studio right now. Then we worked with the design team to bear that out. And it helps you find financing partners too.

Do you feel that had an effect on the creative direction you guys took your project? I'm sure that after all these years, as with everyone who works in a creative field, you had plenty of ideas, right?

AR: Yeah, absolutely. We're very pragmatic. I mean, the nature of the work we do, being in the work-for-hire business, meant we've had to be a bit more careful and a bit more professional. We're not really a "work hard, play hard" kind of place, and that pragmatism and professionalism has led the pitches for properties, and that process comes from the employees.

We've tried to instill a culture here where people don't just think about their super quirky project, but also what they think will play well and what will be sellable. We do a "game of the week" contest where everybody writes a title on a whiteboard -- well not everybody, we have five titles, and we're trying to pick which one we're going to buy that we're going to play at lunch for the following week.

We all vote on them at the weekly staff meeting, and people have to pitch the game in one or two sentences. Even that little cultural feature of the studio gets people thinking about, "Well, my game, that is going to sit on the shelves, or be a downloadable title, has to be able to sell itself in a couple of sentences." It's interesting to see the dynamic, when people realize how hard it is to capture an idea in two sentences, and I think that finds its way into their own design.

Do you think that pragmatism is the key to making something that, in the end, could be a success from a publishing perspective?

Do you think that pragmatism is the key to making something that, in the end, could be a success from a publishing perspective?

AR: I think in the game industry, we are short on pragmatism, for sure. I don't think that it's more essential than being especially creative, or having brilliant, distinctive artwork, but I think in the game industry, especially in smaller studios, people are not practical.

They sometimes need to be more realistic about what the marketplace wants, not what their little dream game is. I think we have been able to marry what the market wants with what our dream game is nicely; I'm excited about that.

I think what's disappointing is when people's dream game is really boring, which happens a lot.

AR: (laughs) It's interesting. When people pitch ideas, it takes place at lunch, so you have to stand up in front of the studio and say, "here's my idea for a game." People do little PowerPoint stacks, or sometimes just a piece of artwork.

When getting up in front of people to talk about your title, it's amazing how quick the people giving the pitches realize the flaws in their ideas, and what is really a home run in their ideas, based on having to stand up in front of their peers and talking about it. It works incredibly well.

Does that lead to refinement or rejection of ideas, do you think?

AR: Oh, refinement, for sure. It causes people to extract the little gems in this bigger idea that they have that will really resonate and push back the stuff that didn't sit well with people. It's pretty rare for somebody to make a pitch here and then have it be D.O.A. Almost always, there are follow-up discussions in the design department about what's working and what isn't.

It sounds like you take pitches from people no matter what discipline they're working under, but then design takes a look at them.

AR: Yeah, definitely. We treat designers here as -- it's a professional skill, like engineering, like artwork. For the whole studio, there's a wonderful talent pool there and a lot of brilliant thinking, but design is a job and we hire people with that title who are designers for a reason; it's because they're able to design games. We want to make sure they're involved in the process as early as possible.

There's always a back and forth -- I talk to a lot of people who work at a lot of different studios, and it seems like that design is still... not 100 percent nailed down, shall we say?

AR: Sure. One of the things I've learned personally, in particular, over the past few years, working with the designers we have here, is I thought -- as recent as two or three years ago -- "Well, anybody can be a designer, and it's something you do in addition to engineering, or production, or artwork, or whatever it is."

But working with the design team here, that we've managed to bring to the studio, I've learned very much that it's a professional skill, and there are people who are so much better at it than I ever imagined. Working with them is super humbling.

The founders and I, we started butting out of the design process, because these people are professionals, they know what they're doing, and we should have them design our games. That's why we hired them. There are plenty of studio heads that have that design instinct, but I am not one of them.

I think to a point, everyone thinks they can design a game in their head, right? We all play games, the industry is full of people who love games, so...

AR: Well, it's like writing. Anybody who is literate can write, but that doesn't make you a writer. I think a lot of people make that mistake. Like I can design, but that doesn't make me a designer.

I remember when you announced you were doing the PC version of Mass Effect, there was a real emphasis of your studio's understanding of actually creating a unique interface for the PC audience and that was recognized by the players. Is that something that is a part of your studio's DNA?

AR: Sure. Well, I think all the great developers understand their audiences. With Mass Effect, that's another example of a project where quality was a priority. There may have been other studios that walked from that project, because they're like, "Well, it's the PC SKU of a BioWare game, but it's just the PC SKU." And we looked at that as an opportunity.

What we always touted around the office was the idea was: "We are making a game for the PC and the content has been done for us. What do we need to do?" -- and just trying to look at the project from a fresh perspective.

And BioWare gave us -- maybe a longer leash than they wished they had in the end -- but they gave us the creative freedom that was needed to make Mass Effect on the PC phenomenal, rather than making Mass Effect for the 360 work on the PC. It was a long project too; I think we took 15 or 16 months to put that together.

Mass Effect

That's a long time for a quote-unquote "port."

AR: Oh! Evil word! (laughs)

That's why I put it in air quotes! You don't like that word, though?

AR: It's a naughty word here because of that project. We want to do what's right for the platform. It is what it is, but it definitely has a negative connotation now, so we try to avoid using it.

I think it has a negative connotation outside of your studio too, which is why people were so gratified by that version.

AR: Right. And to BioWare's credit, we told them, "This is what we want to do." And they said, "Yes, that's absolutely what we want!" And their roots are, of course, as a PC developer, so they have their fans in mind, and they trusted us with their fans, which was an honor, frankly.

I don't think I became aware of your studio personally until probably Mass Effect, and that's probably because you guys are a bit behind-the-scenes.

AR: Yeah, for sure. That's been really tough with us. That's why we work with [PR] Tracie. When you're working with big brands, like Rock Band, you're working with big studios, like Harmonix, who is owned by MTV, who is owned by Viacom -- these huge corporations -- it's easy to get lost in their shadow.

And that's part of our role, right? They are the stars, and we're working with their brand, hoping it shines brighter than it was before. That's a real challenge for us.

That's one of the things that is super exciting about working on our own property, is brainstorming how we're going to do the marketing ourselves, if that ends up being the right thing to do, and what the angle for that is going to be. It's a lot of fun; it's re-kindled my entrepreneurial spirit that got Demiurge started in the first place. That's easy to forget about when you get big and you're dealing with the day-to-day.

There have been some examples this generation of some studios stepping out with their own IP after having a history of working with a specific IP, and kind of hitting the wall. Have you been really observant of some of those games? What do you think about that issue? You said there aren't that many second chances.

AR: I can't actually think of an example of what you're talking about, but --

Okay, Mirror's Edge, Dark Sector are two really good examples of, "Whoops!"

AR: [incredulously] Mirror's Edge?

Yeah. It's good, but --

AR: Oh my goodness, I love that game!

I'm not saying it's not a good game --

AR: But I understand it was not a sales success.

Yeah.

AR: The game that we're working on right now, it's not our first original property idea, but I think it will be the first one that consumers will be able to buy. We've been trying and failing at this for a very long time now, and it's hard.

It's hard in a way that was totally unexpected to me. In all respects, when working with someone else's license, the hard work is done for us. We don't have to ask ourselves when working with Mass Effect, "What color should the spaceships be?" because BioWare gives us the art style guide and says, "These are the colors of our spaceships."

Trying to figure that stuff out is immensely time consuming, and it is really tough work. The creative people around here are writing off that blank sheet of paper over and over and over again until the project finds its voice.

By "failing," do you mean that these projects were ones where the stars didn't come together?

AR: Well, I think you make mistakes and you learn from them, is my point. We would, either in the path of creating intellectual property, get too far down the road when it had some fatal flaw that we had to go all the way back and undo, or you learn from heading down the wrong path, a particular design, a particular art style, so...

Things that hit the market tend to resemble other things that hit the market. Some of that probably has to do with the safety of that, but it also has to do with that blank sheet of paper you just alluded to, right? Filling it up is not the easiest task, to say the least.

AR: Well, also, great minds think alike. You see it in the film industry too, obviously. It's very difficult, it's heart wrenching, it's time consuming, and it's expensive, but we had a taste of it. Our first year, we put out an Unreal Tournament 2004 mod called Clone Bandits.

It was like a little mod we made with vehicles, and it had a cool soundtrack, and it was free, and it was nights' and weekends' work. But that project had tone, and soul, and voice. It took a long time, but then all at once it fell together and we're like, "Ah, this is great!" So that's what we've been trying to duplicate ever since.

We've succeeded a couple times, but we haven't been able to marry that with a studio that was ready for it, or a financial situation that was ready for it, or a marketplace that was ready for it. I think now all those pieces have fallen together for us for this project.

Borderlands

The weakness of some game concepts that you see make it to market -- I'm not speaking specifically about anything here -- is that you can tell there's a sort of vagueness, where you can tell they let the dots connect themselves without doing the hard thinking about what goes in there.

AR: But -- Mirror's Edge was a great example -- that had heart. Maybe not everybody agrees with me, but I thought it was beautiful, and it had rich style, and this really cool personality, and it knew what it wanted to be and it was that. That is actually harder, I think, than making a marketable game. That was DICE, right? So they know what they're doing and then some. If you can take that and marry it with something that's marketable, that's gold.

Working on Borderlands was really neat. We watched that project, pretty far into development -- you can compare the old trailers and the new trailers, the very first trailers and the very first magazine covers with what the game became and what its tone was; you can see a progression there. Gearbox found its way. It was an incredible learning experience for us to watch that happen. It's tough. It was hard for them, and they worked their asses off, but it totally came together in the end.

That game is well-known for being a good example of something that's left-of-center, but you're not so far out to the left... You're far enough away that it's got its own spirit, but you're close enough to the goal that it's comprehensible, right?

AR: Gearbox is a studio that knows their audience, and they work so hard at thinking about what their customers want. They think about their customer; you'll hear that when you meet with them.

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like