Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

In this extensive Gamasutra interview, we talk with MIT professor and author Henry Jenkins on the 'games as art' debate, Second Life's contribution to participatory culture, and how games are like bits of fur and silk in our desk drawers.

As one of the foremost academic commentators on contemporary media Henry Jenkins has made a major impact on discussions surrounding games and their place in our culture. His ideas suggest that by examining how people appropriate and recombine different media we learn much about the nature of those media forms within contemporary society. This, as well as much of Jenkins other work, focuses on the nature of interactivity, and that often means video games. He is an MIT professor, a contributor and speaker at media conferences, and an influential author. His latest book, Convergence Culture, articulates Jenkins' most recent theories of how individuals interact with modern media.

GS: What games do you regular play yourself? Are there any games you recommend to other people? (Do these games coincide?)

Henry Jenkins: As a gamer, my preferences tend to run towards casual and puzzle games (especially classics such as Tetris, Snood, and Super Collapse), simulation games (anything by Will Wright), and the classic sidescrollers (Shigeru Miyamoto's games were my first love). The more I get sucked into the world of games research, ironically enough, the less time I get to play games. These days, I am most likely to end up playing Guitar Hero, which is a favorite in the graduate student lounge here. I'm not particularly good at it, which means that students often want to play against me. Getting your head handed to you by one of your students is payback for all of the demands I make on them in the classroom.

GS: I first encountered your work with the 'Eight Myths Debunked' piece. Do you think any of those myths are likely to be dispelled any time soon?

HJ: Those of us who care about games are going to be confronting these particular myths for some time to come. Each myth is very deeply rooted in our culture and has become almost the established wisdom among those people who are not themselves gamers and have very little exposure to the medium. They are the things you think you know when you know nothing else about games and that makes them especially hard to combat. Keep in mind as well that there are all kinds of groups and individuals who have a vested interest in spreading fear and ignorance. They play upon these misconceptions and regularly reinforce them through their comments in the press.

HJ: Those of us who care about games are going to be confronting these particular myths for some time to come. Each myth is very deeply rooted in our culture and has become almost the established wisdom among those people who are not themselves gamers and have very little exposure to the medium. They are the things you think you know when you know nothing else about games and that makes them especially hard to combat. Keep in mind as well that there are all kinds of groups and individuals who have a vested interest in spreading fear and ignorance. They play upon these misconceptions and regularly reinforce them through their comments in the press.

Some of these issues are cyclical: they get battled back, there is a lull, and then some new activist emerges to exploit the ignorance and try once again to push through laws or score legal victories off of many of these issues. You don't hear much these days from David Grossman; Jack Thompson is the current poster child for this perspective, but I have the feeling that he will soon fade from view, and someone else will rise up to take his place. Each has depended upon a slightly different inflection of these myths and so we will see these things get reconfigured once again. Long term, some of these myths will be harder to sustain as more and more of the kids who grew up playing Super Mario Brothers step into adult roles as first time parents, starting teachers, members of the work force, staffers for government agencies, and journalists.

GS: Why do you think people keep raising the 'are games art' debate?

HJ: On the one hand, people keep raising this issue in the positive sense because they are fighting for appropriate recognition for the many men and women who do great work in this medium. Let's give credit where credit is due. Games as a medium has come of age and has produced work which would command our respect in any other medium.

For me, there are other things at stake. If games get considered as an art, then there may be greater respect for innovation, experimentation, diversity, and individual expression within the games industry. Through my blog, I have been promoting for some time the idea of independent games. In other media - comics, film, even television - there are prestige products which get made because they are important for artistic rather than purely technical reasons and there is room to reward the most gifted talent by allowing them to pursue certain dream projects which may or may not end up making huge return on investment. Yet, which game designers are getting to really push the medium or explore new territory right now?

There needs to be counter pressure placed on the games industry to ensure that these designers get greater creative freedom, and there needs to be a concerted effort to educate the games playing public about the value of groundbreaking and genre-bursting titles. I also think artists feel differently about their work than contract workers in an industrial mode of production do. Thinking of games as art may encourage designers to explore alternative aesthetics - rather than being locked into a world where photorealism is the only option - and it may push them to think more deeply about what they are saying through their games rather than simply how it works technically. So, this is a fight worth pursuing.

Addressing your question from the other side, we might ask where the resistance is coming from. It is coming from partisans of other arts. It comes from film critics who are worried that their preferred medium is going to be superseded. It is coming from literary critics who are concerned that young people are playing games rather than reading books. It comes from those whose notion of art is so narrow that very few works qualify as opposed to those of us who have a fairly expansive notion of art and are willing to welcome in new aesthetic experiences. It comes from gamers who worry that calling games art means that they are going to become too obscure and pretentious (small danger there, guys). It has to do with our totally messed up notion of what constitutes art.

But then keep in mind that there are still plenty of people who don't believe television can be an artform or that comics and graphic novels aren't, and there's a much longer history of accomplishments in these media than in games.

GS: I was interested to read the press release for the Game Innovation Lab in Singapore. What do you hope that the lab will achieve? (And have you visited the Tiger Balm Gardens in Singapore?)

HJ: The lab represents a real partnership between MIT and a range of Singaporean based institutions - a global collaboration to promote the growth and development of games as a medium of human expression. We envision the lab as a place which will support basic and applied research into games from every possible angle. We will have computer scientists and AI people looking into new games technologies, graphic artists thinking about new visual styles, cultural scholars looking for new cultural traditions or imagining ways to address the needs of under served populations, educators exploring the pedagogical potentials of the medium, musicians exploring new approaches to scoring games, and so forth. Our hope is to rapidly deploy this new research into the development of new games as testbeds for our new ideas.

Obviously, we aren't going to be developing multimillion dollar titles. Our focus is going to be on casual games which point the way towards innovative uses of the medium. What we want to do is to take advantage of the traditional roles university-based programs have performed in relation to other arts - supporting ideas which wouldn't get green-lighted in a fully corporate setting but which might allow us to explore some important aspect of this still emerging medium. Lots of details are still being worked out but it is certainly our goal to produce games that will go out in the world and be part of the larger games culture. We hope to create games people will want to play, think about, and talk about.

Tiger Balm Garden (Haw Par Villa)

As for Tiger Balm Gardens, I haven't been there yet. I've seen pictures. And man would that make for a truly memorable game experience!

GS: I've been reading work by a British psychologist (Richard Wood at Nottingham University) who has been researching what gamers think about their time spent playing games. Many gamers report that they feel like they have "wasted time" when playing a video game, yet are hard pressed to say what they should have been doing with their leisure time. Why do you think this is?

HJ: Well, for starters, we can't rule out the fact that a fair percentage of them probably were wasting time. Seriously, there are ways of engaging with any medium that are productive and ways that are nonproductive. There's nothing especially wrong with unproductive activities. Most of us are overscheduled and overburdened with other aspects of our lives and it ought to be a sacred thing to sometimes goof off with our mates. But I think the issue goes deeper than that. We lack ways of justifying or explaining the value of games as a meaningful form of activity. They are under fire from all sides. Most people treat them as debased and unproductive. And we start to feel guilty because we internalize some of those perceptions and descriptions.

This has long been the case with other forms of popular culture. Television fans often embrace metaphors of "addiction" or "zealotry" to describe their embrace of favorite programs, sometimes using these terms ironically, sometimes accepting the negative valuation of their activity. This is one reason why the debates about games as art or games as education gain so much interest - because right now, they represent ways of defending the meaningfulness of our engagement with games in terms which can be understood, if accepted, by nongamers. They give us a language for talking about the meaningfulness of game play.

GS: Do you think the games development industry needs change its ways? How would you like to see it develop?

HJ: I am saying nothing here that I have not heard from many others working in and around the games industry. Games are moving from an artisanal based economy to one grounded in major studios and that shift brings both advantages and disadvantages. Let's use Hollywood as a parallel case. The studio era in American film is one which many remember with great fondness for the outstanding quality of production overall. The floor is very high. There is a consistent quality to the films produced which is maintained across pretty much every title that was shipped. It is hard to find a bad film - at least a really bad film - made in 1939. But, if the floor is very high, the ceiling is surprisingly low. There is almost no room for individual expression. Even gifted filmmakers are making seven to ten feature films per year at the height of the studio era. They have almost no control over the titles they produce.

Now, we can compare this with what has happened to American film with the collapse of the studio mode of production and the emergence of independent films or simply of a package system where each film is conceived on its own terms. There is much more room for stylistic innovation, much greater diversity, and more opportunities for distinctive artists to do their own kind of work. Yet, there are a great number of bad films made - maybe not in a technical sense, since the technical standards have continued to rise over all, but in terms of the quality of the scripts and performances, certainly. So, the floor dropped and the ceiling rose. Right now, we need to develop at least some greater space for independent or creator-controlled game projects which will bring about greater innovation, expression, and diversity. And we need to create more space at the center of the games industry for at least the best designers to do work that is uniquely their own.

GS: Games are increasingly being regarded as teaching tools. Does the label of 'learning tool' offer video games an opportunity to clean up their act in the eyes of mainstream culture?

HJ: Right now, if we look at the way the games industry defends itself against its critics, it's core argument seems to be "hey, we're not as bad as you think we are." All of the energy, by and large, gets spent arguing a negative - trying to prove that games do not cause real world violence -- and very little time gets spent making an affirmative case for games - that the world is a better place because we have games in it. There are plenty of very good reasons why we should be promoting the educational value of games - after all, they are the preferred medium for the current generation that is working their way through schools; there is more and more compelling research showing the pedagogical value of many different aspects of current game designs. By now, we can all make the argument but so far, the games industry is running scared of the L Word.

Civilization IV

But your question here cuts to one of the two key rationales for why the industry should care about the education and games debate. The first is that educational video games sell. When people ask me these days for examples of serious games? I usually point to Sim City, The Sims, Civilization, Age of Empires, Railroad Tycoon, Flight Simulators - a list which includes some of the top selling games of all time. Look at that list and you can see that nonfictional works - games that model real world processes - perform as well or better in games than they do in any other commercial medium. Second, helping to support the educational value of games may be the single best PR move which the games industry could take in light of the public's continued linking of games to school violence. That's a purely cynical rationale, I suppose, but if that's what it takes to get game companies over the hump in this space, so be it.

From the 1920s on, Hollywood recognized that school based outreach was key to overcoming its own negative public perception problem. They began to produce a certain number of films which were going to be valuable for schools - documentaries, adaptations of literary classics, historical dramas - and developing teacher's guides and supporting materials around them. They gave teachers the tools they needed to incorporate those films into their classes; they offered discounted tickets for school field trips; they talked at educational conferences. They courted the schools as a major market for their films once their commercial run was over.

These are the kinds of things that the games industry should be doing as well - to help people to recognize the pedagogical value of the games they are already producing. So far, with the exception of the work Firaxis has done around its Civilization franchise, I see very little effort by game companies to support the pedagogical uses of their titles. Surely this is an important first step towards getting greater social recognition of the value of game play.

GS: Could violent video games be a good thing?

Yes, absolutely. Every artform, every storytelling tradition needs the ability to represent violence because aggression, trauma, and loss are a fundamental aspect of the human condition. The idea that game violence is in and of itself bad is an absurdity. At the end of the day, I might push further and say that there is no such thing as game violence - at least the way that it is understood in the popular press. Game violence is not one unified thing which we can label, count, and study in the laboratory. There are various representations of violence in specific games. The issue shouldn't be how much violence is in the game but rather what the violence in a game means.

I am not opposed to game violence per se but I would like to see game designers make more meaningful choices about how they represent violence through their games. There is too much repetitive, banal, thoughtless violence which exists simply because people think it will sell more units. There is not enough violence which has been thought through, which is part of the logic of the game, which makes some kind of statement. You can't really call it gratuitous when the whole purpose of some games is to display violence, but it is certainly a wasted opportunity. Game violence is often so formulaic that it betrays the medium within which these designers are working.

Game designers need to stop thinking about violence as an ethical lapse and start thinking about it as a creative challenge. What can we do that will get designers and players to really think about the role of violence in their work? It is easy enough to defend the role of violence in the work of Scorsese or Tarantino. It is much harder to defend the role of violence in most video games. But this goes hand and hand with what we have been saying about game as art: with creative freedom must come creative responsibility.

GS: We're seeing a lot of coverage of Second Life, but how important do you think The Linden's project really is?

HJ: I think what is going on in Second Life is profoundly important on several levels. At the most basic level, it probably represents the furthest the game industry has gone in the direction of user-generated content. It is utterly fascinating to see what people are choosing to do within the context it provides for them to create stuff, make stuff happen, and share stuff with other people. (I am using stuff here because it signals just how diverse the range of materials and activities these communities are generating are.)

Second Life

Second Life ranks alongside YouTube as perhaps the most visible example of the kinds of participatory culture I discuss in my new book, Convergence Culture. It is a powerful example of consumers taking media in their own hands. Will every person want to build things? No - most of us don't build things in real life. But a world where any one of us could potentially build something and get it into cultural distribution feels different than one where creativity rests in the hands of a talented few and the power of distribution

resides purely with an ever smaller number of major media companies. I suspect most of us will want to consume rather than produce media. But I am sure glad that there are people out there making media for no other reason than because they can.

And like YouTube, Second Life represents a meeting point between different subcultural communities - and now, increasingly, commercial, educational, nonprofit, and governmental institutions as well. Last week, I participated in a major press conference hosted by the MacArthur Foundation. On one hand, we were speaking to key civic leaders from the Manhattan area - directors of school systems, museums, libraries, and other public institutions - inside the Museum of Natural History. On the other hand, we were speaking to people who levitated or had feathers growing out of their heads who were listening to the event via Second Life. All kinds of groups are using Second Life as a platform for what one might call thought experiments - trying things out in a virtual world that they would not be able to do in the real world - and as this happens, we are seeing Harvard try to teach law courses, therapists doing group sessions, advertisers testing brand strategies, and sexual minorities trying new kinds of practices, all in the confines of this virtual world. Some of the things people are doing right now will turn out to be dead-ends, but I love the generative nature of Second Life and I am convinced that some major discoveries will emerge through this outburst of bottom-up energy.

GS: Do you think that preconceptions about 'gaming' are hindering the development of online worlds into a genuine of a 3D-web or 'metaverse'? (I'm thinking about Prokofy Neva's comments in this comments thread):

HJ: I have long felt that the term, game, is both enabling and crippling. We have a tendency right now to describe all forms of digital entertainment as games. In the real world, we might maintain meaningful distinctions between games, sports, toys, playgrounds, theaters, artistic tools, community halls, and so forth, all of them become games when computers are involved. This can be seen in an elastic sense - the word just keeps expanding to include all new play experiences - but it can also be done in a very constricting sense - creating a hierarchy of experiences based on how much they do or do not look like a prototypical game. So, the argument that "this isn't really a game" gets used to shut down games for girls or educational games or serious games or anything that doesn't look like something a hardcore gamer might want to play.

I think it is unfortunate that these online worlds are being hijacked by the term, game, so that we are now hearing Second Life isn't really a game - as if this is a bad thing - and there are people out there who don't play games who won't visit Second Life because they think it is a game. Part of the problem is that we go to games expecting to be entertained, anticipating predetermined roles and goals and rules and all of that stuff, and that may or may not be the best way to think about how a metaverse might work. There are things designers of online worlds can learn from games but there are also things they should be learning from MUDS or chat rooms or all kinds of other communities online and off.

GS: What other media do you think video games can learn most from? Are there any film-makers, sculptors, or architects whose concepts you think should be incorporated in game worlds? (I realize this is an absurdly broad question, but folks often come up with "Hell yes, I want to see a video game of Warren Ellis' Authority, which always makes me smile...)

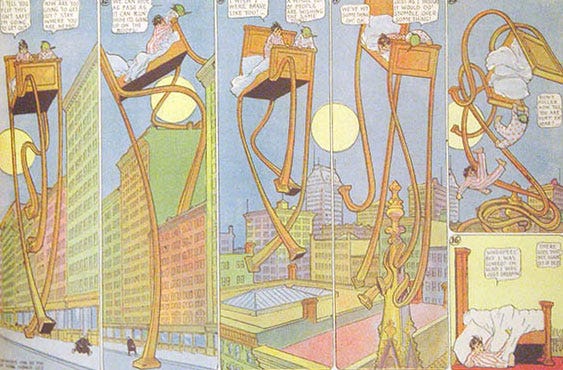

HJ: That's the wrong way to think about it. I'd love to see a game world that worked like Winsor McCay's Little Nemo, like Einstein's Dreams, like Salvador Dali, like Doctor Seuss, like Matthew Barney, like.. We can make a laundry list of our favorite artists, many of which might inform and inspire the right designer under the right circumstances to create something really incredible. But just as I don't think the best films are adapted from stage plays, I doubt the best games will come from slavishly imitating work from another medium. What I really want to do is see more game designers given the creative freedom to do expressive experiments in this medium, to take it places we never thought it could go and make it do things we never would have imagined possible.

What all of the examples that came to me first have in common is that they have nothing in common. They represent radically different ways of representing the world. Well, that's not true - they have in common the fact that none of them represent photorealism. In every other art, realism is an aesthetic choice. In games, it has become a technological imperative. But I would still argue that many of my favorite games - the work of Miyamoto comes to mind - don't look or act like the world we live in. The brilliance of Super Mario Brothers, and the reason it made me fall in love with this medium, was that it represented a fully realized yet totally idiosyncratic microworld. I loved the imagination and whimsy that went into its design. I want to see games find their way back to that place.

Little Nemo in Slumberland

GS: Lars Svendsen's 'The Philosophy of Boredom' identifies boredom as a peculiarly modern problem. JG Ballard meanwhile predicts that "the future will be boring" and that psychopathological experiments will fill the void. Could it be that in fact video games (themselves often experiments in strange and violent activities) will fill that void, and be a peculiarly modern antidote to the peculiarly modern problem of boredom?

HJ: I am the wrong person to ask this question. Boredom isn't part of my day to day experience. Exhaustion is. And unfortunately, real exhaustion is not a problem which can be addressed through games. When I am really exhausted, I just want to collapse on the couch and be entertained. Exhaustion drives me to television far more than it pushes me to games. But games can address fatigue - which is one or two levels before you get to exhaustion. They are a true recreational medium.

We've lost a sense of the original meaning of recreation as in to re-create, to re-vitalize, to re-fresh. At the turn of the last century, people were convinced that the drabness of modern life, the repetition of the workplace was going to grind down our sensory apparatus to the point that we would be incapable of responding to new stimuli. Reformers advocated all kinds of crazy ideas - like keeping fabrics of different textures in your desk drawer to fondle during odd moments during the workday - as remedies to this problem and our modern value on recreation grew out of this idea that we needed to recreate ourselves and refresh our senses from time to time.

Today, we don't keep bits of fur and silk in our desk drawers. We simply can boot up a casual game during our break times and go off into a fantasy world during our lunch hour. But the function is the same. I suppose I am saying that this is not a peculiarly contemporary problem - there's a long history of this notion of refreshing our perceptual apparatus and today's casual games fit into a much older discourse about how we can gain some personal fulfillment between the demands of our jobs.

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like