Clone Wars: The Five Most Important Cases Every Game Developer Should Know

"How courts treat developers copying ideas for video games, however, has quietly but dramatically evolved over the past year," writes attorney Stephen McArthur, who takes a look at how the legal precedent on cloning has changed from Asteroids through Triple Town.

February 27, 2013

Author: by Stephen C. McArthur

"How courts treat developers copying ideas for video games, however, has quietly but dramatically evolved over the past year," writes attorney Stephen McArthur, who takes a look at how the legal precedent on cloning has changed over the years -- from Asteroids through Triple Town.

Nothing can be wholly original when every idea and expression is inspired by what came before it. In that sense, all of creativity is derivative. From the earliest days of the wave of Pong clones in 1976, copyright law has been rather ineffective for video game developers who have tried using it to protect their games from competition.

How courts treat developers copying ideas for video games, however, has quietly but dramatically evolved over the past year. Courts are suddenly more willing to aggressively apply the principles of copyright infringement to the age-old practice of borrowing the game mechanics from an already successful video game, changing the art and design, and presenting it as something new and different -- i.e., "cloning".

There has always been a fine line between innovation and shameless copying in the video game industry. On the one hand, a developer shouldn't retain a monopoly over an entire genre of games, since it can serve as a platform for third party creativity.

If the developers of Wolfenstein 3-D were able to monopolize the idea of the first person perspective of a protagonist winding through levels using guns and other weapons to destroy enemies, then we wouldn't have Halo or Call of Duty.

If too much copyright protection is awarded to a game developer, then it could end up owning an entire genre and shutting out creativity for decades. On the other hand, we want to award innovation at companies, big or small, that create new ideas rather than simply following the trend of cloning whatever game or idea is popular. Drawing the line is not an easy task.

Historically, the courts have been unavailing to video game developers bringing copyright infringement lawsuits against cloners. However, in May 2012, a federal court cracked down on a mobile game developer that created a game that had remarkably similar art to Tetris and identical gameplay.[1]

Going one step further, in August, a second federal court shut down 6Waves's attempt to ride off of Spryfox's Triple Town success with its own mobile game, Yeti Town.[2]

The Triple Town case is remarkable since the court used copyright law to protect Triple Town's hierarchical tile-matching gameplay, essentially granting copyright protection to the rules and functionality of a video game instead of strictly to its audiovisual display. Are these two recent cases simply an anomaly, or are they a reaction to a perceived trend of rampant copycatting in the gaming industry and do they portend a new era of courts protecting existing games with the copyright regime?

A Brief Overview of the Law

The raison d'être of copyright law is to encourage the production of new art by rewarding authors for their creative efforts. Copyright protects artistic and literary expression. A video game's underlying code is protectable as a literary work and its art, music, and sound effects are protectable as an audiovisual work.

Copyright law does not protect against the borrowing of the underlying idea in a creative work - only the specific expression of that idea.[3] The rules, game mechanics, and functionality of a video game are said to "merge" with the underlying idea.[4] This means that game mechanics and the rules are not entitled to protection. Only the "expressive elements" of the game are copyrightable.

In Defense of the Ancients, for example, the underlying idea might be described as a multiplayer online battle arena where players are on either of two teams. Each player controls one character for their team and uses teamwork to attempt to defeat other enemy player characters and ultimately destroy the opposing base. That underlying idea cannot be copyrighted and there are untold thousands of ways to express it. Any original expression of that underlying idea, such as Riot Games' League of Legends, is protected by copyright.

Once you have an understanding of what can and cannot be protected by copyright, the next step is to learn how a copyright might be "infringed." To establish copyright infringement, a plaintiff must prove that it owns a valid copyright and that the defendant copied its work. The plaintiff can prove the defendant copied by showing that the defendant had access to the copyrighted material, and that there is "substantial similarity" between the protectable elements of the two works. "Access" to the copyrighted work is usually uncontested, since video games are generally widely distributed. The key analysis to video game copyright infringement most often centers on substantial similarity.

All creativity is derivative, so copyright law cannot absolutely prohibit any copying from prior works. In fact, when Atari, the creator of Asteroids, sued Amusement World, the creator of Meteors, for copyright infringement, Amusement World admitted that it made its game because it was inspired to make a "better version" of Asteroids.[5] Nevertheless, Atari lost its copyright claim, since the two games were not considered substantially similar. Substantial similarity means that the degree of similarity between the works is so high that the similarities could only have been caused by copying.[6]

When comparing two video games for the substantial similarity analysis, the court will only consider the protectable elements of the copyrighted work, and will filter out all "unprotectable elements".[7] The most common unprotectable elements of a video game that cannot be used for a substantial similarity analysis are (1) elements that are not original to the copyrighted work, and (2) scènes à faire, French for "scenes that must be done." Scènes à faire are features that are necessary or common to a genre.

Consider a video game based around vampires -- stakes through the heart, coffins, garlic, and an antagonist who sucks blood from his victims and avoids the sunlight are all standard to the vampire genre, and thus are scènes à faire, unprotectable elements of a video game.

When the unprotectable elements are "filtered" out, what's left is the author's particular expression of an idea, and that is what is compared to the accused copycat work through the eyes of a theoretical "ordinary reasonable observer."

The key to remember is that it is the plaintiff's burden to prove that a defendant's alleged copying is improper by demonstrating substantial similarity of the protected creative elements of each game. The underlying idea of the video game, including the rules and game mechanics, are not copyrightable. Only the original expressive aspects, including the code, artwork, and sound, are protected by copyrightable law.

A History of Courts Allowing Video Game Clones

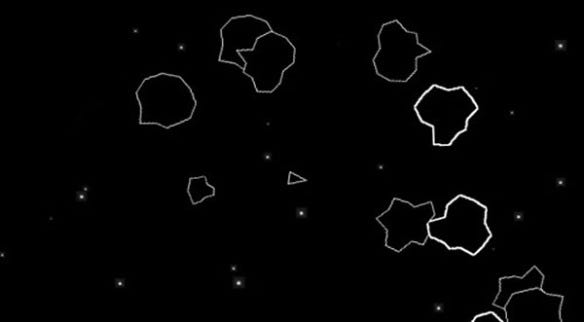

Asteroids and Meteors

The predominant pattern in video game cloning cases has been for the court to rule definitively for the defendant. Illustrative of this long history is Atari's 1982 lawsuit against Amusement World, a decision that paved the way for developers to create games closely resembling established and successful games first created by other companies.[8]

Atari released the groundbreaking game, Asteroids, in 1979. In Asteroids, the player controls a triangle-shaped spaceship that must shoot and destroy opposing asteroids and enemy spaceships until it is hit and destroyed. Asteroids was an instant hit. Two years later, Stephen Holniker of Amusement World played Asteroids and said to himself, "I can do better". [9]

In 1981, Holniker released Meteors, what most would describe today as a "clone" of Asteroids. Atari sued the smaller company for copyright infringement.

Asteroids.

Meteors. (Gameplay footage begins around 2:00)

The court easily identified twenty-two similarities between the two games and acknowledged that Amusement World had intentionally based Meteors off of the idea of Asteroids. Both were 2D games involving a spaceship shooting its way through waves of larger and larger rocks that split into smaller ones when shot.

They shared seemingly arbitrary numerical qualities: there were exactly three sizes of space rocks in both games, the largest rocks always split into two medium rocks which would each always split into two small rocks. A player received an extra life in each game as soon as he scored 10,000 points. The player's spaceship was destroyed from only a single hit of any rock.

The rocks appeared in progressively larger waves and new waves would appear as soon as the final rock of the previous wave was destroyed. Large rocks moved slower than smaller ones. The controls for moving the spaceships were functionally identical. Both games even included a "thrust" function that moved the spaceship forward but then gradually slowed the spaceship down when the button was released.

Despite all of those similarities, the court held that there was no "substantial similarity." Most of the apparent similarities between the games were necessary if one was going to develop a game with the basic, unprotectable idea of shooting down space rocks with a spaceship. The similarities were thus scènes à faire and a necessity of the genre. The remaining similarities were functional game mechanics and rules, which are not copyrightable and thus could be copied by anyone. As the first case to apply these principles of copyright law to a video game, Atari's loss was a watershed event in the history of video game cloning.

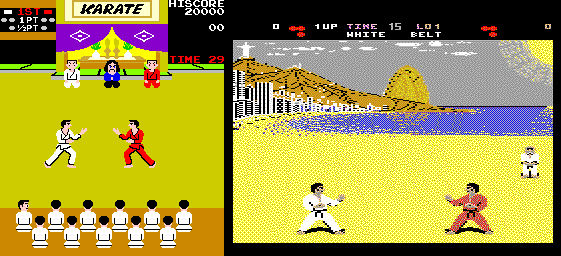

Karate Champ and World Karate Championship

Six years after Atari's failed lawsuit, Data East sued Epyx for copying its successful karate fighting simulation game, Karate Champ.[10] The court wrote that Karate Champ and Epyx's World Karate Championship had 15 noteworthy features in common, many of which were martial-arts moves.

Left: Karate Champ. Right: World Karate Championship.

Left: Karate Champ. Right: World Karate Championship.

Nevertheless, the court held that each of those features were unprotectable, reasoning that certain karate moves, the presence of a referee, and the scoring system resulted from either constraints inherent in the sport of karate or from the existing technology. Once the court filtered all of the unprotectable elements (scenes à faire, unoriginal concepts, and functional gameplay rules) what was left of Karate World was not substantially similar to World Karate Championship.

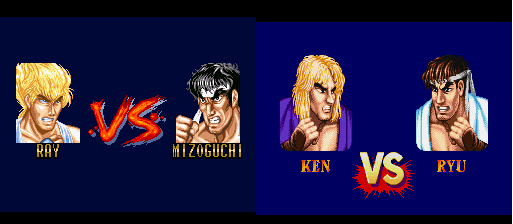

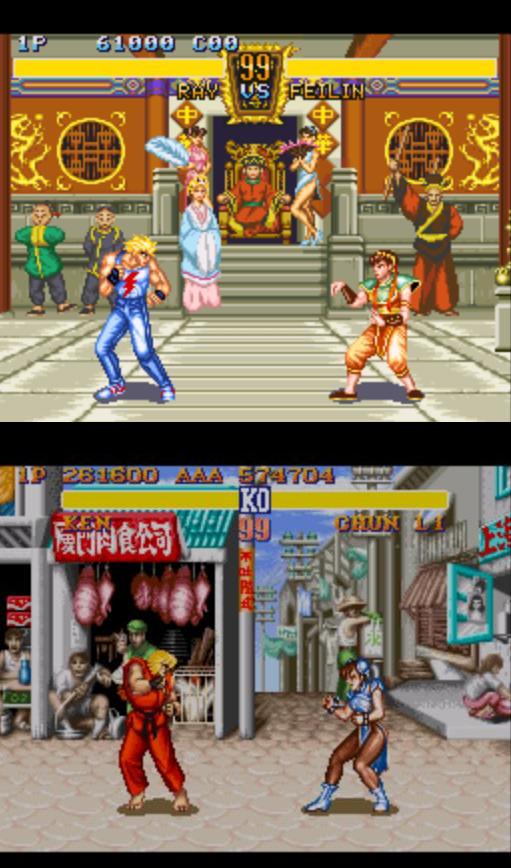

Street Fighter and Fighter's History

Ironically, Data East found itself on the opposite side of a copyright lawsuit six years later. Data East developed and released a six-button fighting game called Fighter's History in 1993.[11] In Fighter's History, two players chose a fighter to square off in a side-view battle with punches, kicks, and special moves until they reduced their opponent's health bar to zero. Each fighter had three different punch buttons and three different kick buttons, one for each of light, medium, and heavy strength levels. If this sounds familiar to you, that may be because you have played Capcom's Street Fighter II, released two years earlier in 1991.

The two games claimed the same genre and had similar functionality and gameplay. But we've learned from the earlier cases that what matters is the "expression" of those underlying ideas and whether the protectable elements of the games are substantially similar. In support of Capcom's case of copyright infringement, though, the games did look strikingly alike:

Left: Fighter's History. Right: Street Fighter II.

Top: Fighter's History. Bottom: Street Fighter II.

The court even acknowledged that Data East had deliberately imitated Street Fighter II in hopes of capturing its success. Once again though, none of this was good enough for the court to be convinced of copyright infringement. In fact, the court ruled that Capcom failed to demonstrate a likelihood of success on the merits and denied its request for a preliminary injunction.

The court found that Street Fighter II was itself based on stereotypical characters (scènes à faire) and hundreds of fighting techniques that were already part of the public domain before Capcom appropriated them for Street Fighter II and were thus not copyrightable.

In fact, Data East had been creating games in the fighting genre (like the aforementioned Karate Champ) years before Street Fighter II was released. The unrealistic fighting maneuvers, such as the ability in each game to shoot fireballs from a character's hands were not substantially similar, because expressive details such as color and iconography were different.

What the Street Fighter case demonstrates is that even if a defendant creates a game that is incredibly similar to another very popular, antecedent game, that defendant can help avoid copyright infringement if it has already established an earlier practice of creating games in that genre.

Two Recent Cases Suddenly Limit the Practice of Cloning

The Asteroids, Karate Champ, and Street Fighter II cases are simply a few representative examples of about a dozen cases resulting in favorable rulings for developers accused of "cloning," even where those developers had purposefully imitated the original work.

In 2012, however, two federal courts cracked down on accused video game clones, extending the principles of copyright law more aggressively than cases of the past thirty years.

Tetris v. Mino

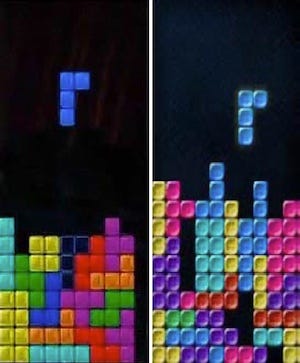

In May 2009, Xio released Mino, a game wholly inspired by Tetris.[12] Apparently banking on the three-decade history of courts dismissing copyright lawsuits against accused cloners, Xio brazenly copied the rules and functionality of Tetris, and then swapped out Tetris's artwork and sound for its own originally created, yet strikingly similar, artwork. Below are side-by-side screenshots of Tetris and Mino. Can you tell which one is Tetris?

Left: Tetris. Right: Mino.

Xio relied on the fact that there was no patent or copyright covering the rules and gameplay functionality of Tetris. Since Xio had technically replaced Tetris's artwork with its own, it argued that its otherwise "wholesale copying" was perfectly legal.

The court disagreed and ruled against the cloner, Xio. The court found that Tetris and Mino looked virtually identical and that a player might not know which one of them was the real Tetris. It granted summary judgment in favor of Tetris.

The court was troubled by the fact that not only had Xio strictly copied the exact rules and functionality of the game, but its own version of the artwork and audiovisual display was so similar as to be easily confused with Tetris even by those familiar with both games.

The court wrote that it was "the wholesale copying of the Tetris look that the Court finds troubling more than the individual similarities each considered in isolation."

The Xio case demonstrates that a developer cannot avoid copyright liability with only trivial alterations to a game's artwork.[13] Xio could have made any number of puzzle games that were inspired by Tetris, had they not been carbon copies.

Triple Town v. Yeti Town

In 2012, Spry Fox accused 6Waves' game Yeti Town of copying its own successful game, Triple Town.[14]

Both Triple Town and Yeti Town are games in the general "tile matching" genre. The underlying idea of the two games is that the player matches three or more tiles of the same object. As the tiles are matched, they transform into a single tile of an object of greater hierarchy. Those new tiles can themselves be matched to create tiles of even greater hierarchy. Frustrating the player's efforts are antagonist objects. Spry Fox's copyright of Triple Town gave it no monopoly for this underlying idea.

In Triple Town, the matched objects progress from bushes to trees to houses to churches and beyond. The antagonist frustrating the player's efforts takes the shape of a bear, and the game includes a "bot" the player can use to destroy any tiles. Triple Town takes place in a woodland setting.

6Waves expressed the underlying idea in its game, Yeti Town, a little differently. Instead of a woodland setting, it was an Arctic setting. The antagonist was a yeti instead of a bear. It used a campfire instead of a robot to destroy tiles. The object hierarchy progressed from saplings to trees to tents to cabins and so on.

Left: Triple Town. Right: Yeti Town.

However, the rules and functionality of the games, especially the object of matching tiles to create the greatest hierarchy, were nearly identical. The court seemed to be troubled by the fact that Yeti Town copied the exact gameplay and rules of the successful Triple Town. Even though Yeti Town's artwork, sound, and underlying code were readily distinguishable from Triple Town's, the court ruled that Spry Fox had in fact stated a plausible case for copyright infringement against 6Waves.

To determine whether the two games were substantially similar, the court performed an "extrinsic test", objectively comparing Triple Town's protectable elements to Yeti Town. Then, it performed an "intrinsic test", a subjective comparison of the protected elements of Triple Town, but through the eyes of a theoretical "ordinary observer" instead of the judge, focusing on the "total concept and feel" of the two works. Relying on the reactions of video game bloggers that called Yeti Town a clone of Triple Town, the court decided that an ordinary observer would plausibly have found that Triple Town and Yeti Town are substantially similar in total concept and feel.

As a result, 6Waves quickly settled and granted all of Yeti Town's intellectual property to Spry Fox. Thus, Triple Town is a momentous case -- since, for the first time, a court has looked far beyond the superficial artwork and audiovisual display, and appears to grant copyright protection to the actual rules and gameplay itself.

In each of the cases we had previously discussed, the video game accused of copyright infringement shared many artwork and other audiovisual similarities with the earlier game it was accused of copying. Yet the courts were still reluctant to find substantial similarity or copyright infringement. Only in the Tetris case did the court find substantial similarity, and in that case the clone was so artistically identical that even an avid Tetris fan would be momentarily confused. But Yeti Town does not share the same striking visual similarities that we saw in the Tetris case.

So, where did 6Waves go wrong in its development of Yeti Town? Why wasn't it able to avoid copyright infringement for its clone when so many others had? If we dig a little deeper in to the facts, we can identify several things that may have turned the tide against it:

Yeti Town mimicked Triple Town's name. The court did not like the fact that 6Waves used the word "town" in its game's title. Even though the game's names aren't technically copyrighted, the court still said it was relevant to the question of substantial similarity.

6Waves may have been involved in some corporate skullduggery. Prior to the public launch of Triple Town, 6Waves and Spry Fox allegedly signed a non-disclosure agreement granting 6Waves confidential access to the Triple Town beta so that it might publish it on social networking sites like Facebook.[15] Negotiations eventually broke down and Spry Fox decided to self-publish Triple Town in October 2011. Two months later, in December 2011, 6Waves released Yeti Town. 6Waves denied copying Triple Town and claimed that Yeti Town had been independently developed by a third party.

Bloggers can make a difference. The court relied heavily on video game bloggers' reactions to Yeti Town, many of whom called the games similar and pointed out that it was obviously inspired by Triple Town. The court anointed bloggers to be quintessential "ordinary observers" and wrote that they had found the two games "substantially similar."

The judge never actually played either game. The judge even complained that "it is difficult to compare two video games by looking at a few screen shots and reading written descriptions of game play".[16] Without actually playing either game, it might be difficult for someone to understand more nuanced differences between the two, especially for most judges who probably did not grow up playing video games and aren't as familiar with them. It is possible that the judge's conclusions derived from a lack of familiarity rather than a misappropriation of the protected expression.

The court did not consider what was different about the two games. It may come as a surprise to learn that whether a developer has added features or even made the game better in his "clone" is not relevant to copyright infringement.[17] For example, it was not relevant to the court that Yeti Town had added a "3D tilt" feature to its game. You cannot shield yourself from misappropriation liability by adding features and improving the game.

The recent Tetris and Triple Town cases have nudged copyright closer to protecting game mechanics and may demonstrate a shift in the attitude of courts to cloned games. But are they enough to counteract a three-decade long pattern of victories in favor of alleged cloners? Ultimately, it's up to the courts to strike an equilibrium between shutting down the most egregious of clones without extending copyright protection to rules and game mechanics, which could create monopolies in entire genres of games.

Stephen McArthur is an attorney that focuses on intellectual property and privacy law and litigation at The McArthur Law Practice. You can read more about his practice at www.thevideogamelawyer.com. This article is for general information purposes and is not intended to be and should not be taken as legal advice.

---

[1] Tetris Holding, LLC v. XIO Interactive, LLC, 2012 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 74463 (D. N.J., May 30, 2012).

[2] Spry Fox LLC v. Lolapps, Inc., 2:12-cv-00147-RAJ (W.D. Wash. Sept. 18, 2012).

[3] § 102(b) of the Copyright Act codifies this rule, known as the "idea/expression" dichotomy.

[4] Allen v. Academic Games League of America, Inc., 89 F.3d 614, 617-618 (9th Cir. 1996).

[5] Atari v. Amusement World Inc., 547 F.Supp. 222 (D. Md. Nov. 27, 1981).

[6] Ringgold v. Black Entertainment Television, Inc., 126 F.3d 70 (2nd Cir., 1997).

[7] Cavalier v. Random House, Inc., 297 F.3d 815, 822 (9th Cir. 2002).

[8] Atari v. Amusement World Inc., 547 F.Supp. 222 (D. Md. Nov. 27, 1981)

[9] http://www.substance-tv.com/return-of-meteors/

[10] Data East USA, Inc. v. Epyx, Inc., 862 F.2d 204, 209 (9th Cir. 1988).

[11] Capcom U.S.A. Inc. v. Data East Corp., 1994 WL 1751482 (N.D. Cal. 1994).

[12] Tetris Holding, LLC v. XIO Interactive, LLC, at 3 (D. N.J., May 30, 2012).

[13] Tetris Holding is not the first case where a court has found copyright infringement in a video game, but it is a recent and representative example of the reasoning courts use when they do crack down on alleged cloners.

[14] Spry Fox LLC v. Lolapps, Inc., 2:12-cv-00147-RAJ (W.D. Wash. Sept. 18, 2012).

[15] Spryfox Complaint, p. 2.

[16] Spry Fox LLC v. Lolapps, Inc., 2:12-cv-00147-RAJ, at 11 (W.D. Wash. Sept. 18, 2012).

[17] "There are apparent differences between games (for example, yetis are not bears and 'bots' are not campfires), but a court must focus on what is similar, not what is different, when comparing two works." Spry Fox v. 6Waves, at 11.

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like

.jpeg?width=700&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)