Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

An experienced coin-op designer from Spain's Gaelco (Smashing Drive) moves into the world of free-to-play games, and notices eerie similarities between the new markets -- and in this article, shares his insights.

I worked in the coin-op video game industry for 13 years, as a graphic artist and game designer. I worked on and created several video games, some of them quite successful. (You can find more about these games at my personal website www.xavifradera.com.)

As my game development career moved forward, I shifted to mobile games, console games and, currently, am in production on a PC free-to-play shooter. I'm in charge of different tasks on this game (game design, production...) and we have just reached the beta testing phase.

The game is a classic F2P shooter, where you can play for free as long as you like, or play and buy some assets to customize your character, buy powerful weapons to better defeat your enemies, create a clan with your friends, customize it, and much more.

During the production and beta testing phase, I found some similarities between coin-op and F2P games regarding how the player approaches the game and how the game approaches the player. This article tries to explain these psychological and game dynamics.

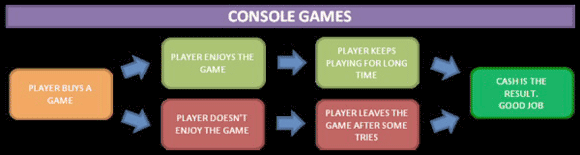

When the player buys a game and plays it for first time, two things can happen:

The player enjoys the game, so he will keep playing for a long time, maybe until completing it. That's perfect, as it's been a good investment for the player.

The player doesn't enjoy the game. His first experience is not what he thought it would be. He will give it another try -- sure he will, as he spent a lot of money on the game -- and another, and possibly another... until he realizes he has thrown away his money.

In both cases, the publisher has sold the game and gotten business -- good job, to the publisher!

Console game player reaction flow chart.

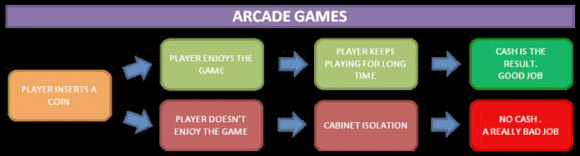

With coin-op and F2P games, the player's reaction during his first game experience is different. What happens if the player enjoys the game?

With coin-op games, he will keep playing and inserting coins for days, weeks or possibly months. Also, be certain that many people will be watching the way he enjoys the game, so when the player finishes playing, new players will give it a try. At the end of the day, the cabinet's coin box will surely be completely full.

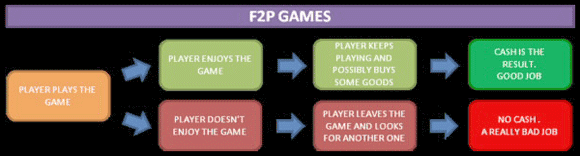

With F2P, the player will keep playing for free. In some cases -- it's said to be 3 to 5 percent -- he will buy some assets or virtual goods to better enjoy the game. At the end of the month, money is in the publisher or developer's bank account.

This is what happens if player's first experience is positive and enjoys the game. In both cases cash is the result. Good job.

But, what happens if the player does not enjoy the game, or maybe gets confused, or frustrated, and has a bad first game experience?

With coin-op games, the player will try the game two or three times before moving aside and waiting for another player to play. If other new players have the same bad experience, people in the arcade will move away from the cabinet, because news spreads like wildfire. At the end of the day, there won't be much money in the cabinet's coin box.

With F2P, a bad first experience makes the player immediately quit and search for another game, because there are so many choices out there. If the game cost the player money, he would have given it another try, but because he hasn't spent even a cent, he just quits.

In these two cases, cash is not the result for the publisher or developer. A really bad job.

Arcade game player reaction flow chart.

F2P game player reaction flow chart.

As you can easily understand, if the game costs money, the player will give it more of a chance, so the game has more time available to let the player get used to it and to convince him it's fun. If it doesn't cost any money, the game has to be fun and intuitive at the first try... or die.

That's why, especially with coin-op and F2P games, player's first experience needs to be absolutely great. It can't be confusing, annoying or frustrating. It has to be perfect at all costs, because if not, the player will quit the game -- the most catastrophic result.

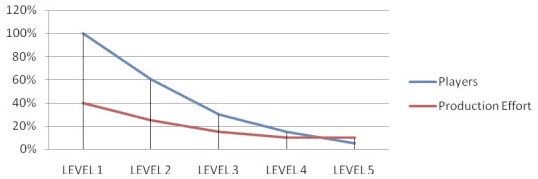

With most games you buy at a shop, replayability is not prioritized. The completely opposite happens with coin-op games; each level will be played hundreds of times by the same player. This is mainly the starting levels, since they are the ones the player has to master if he wants to progress in the game. These levels have then to be thoroughly designed, each centimeter has to be perfect, gameplay-wise. The bulk of the production effort has to be focused on these levels.

Percentage of players playing each level, compared with its production effort.

Therefore, levels can't have bland areas, bad collision, a section which is not fun at all, or a lost opportunity (a good idea that has not been applied correctly), etc. If there's something that can be improved, something that's not fun at all, something wrong or missing... in the end, the player will get bored quickly, or even worse, annoyed, and that will be enough reason to stop playing the game.

A good tip for honing these levels is creating the game prototype for a level much later in the game, so when the first level is created later, all game features are already defined and well-polished, and it's easier to make a better design.

The same happens with game mechanics. If they are not perfect, they will quickly become annoying, and a strong reason for the player to leave the game, too. And remember, with coin-op games, cash does not come at the moment the player buys the game, but only after the player has been playing the game for a while.

With F2P games, the situation is very similar (specially for shooters). The player plays each level thousands and thousands of times in different game modes, so everything has to be perfect: each centimeter of the levels, each game mechanic, no lost opportunities... because, as we know, that means the player will leave the game and look for another one on which to spend his money.

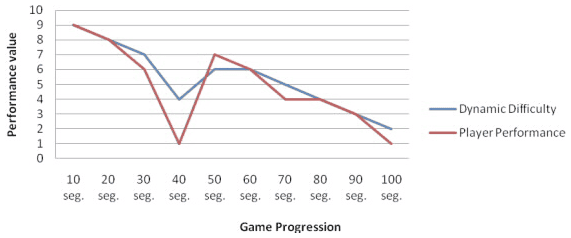

One of the features we added to coin-op games is that game difficulty automatically adjusts to the player's play level. That way, each player has a personalized challenge that makes the game neither too easy nor too difficult, and let the player fully enjoy the game.

Our method was quite simple. We constantly measured player's performance and compared the player's data with the data we got ourselves playing on a perfect match. This let us know the player's skill level after the first five to ten seconds of play. From there, we only had to adjust a few game parameters to match the game to the player's level. During the rest of the game, we kept doing the same: constantly measuring the player's skill and varying the game difficulty slightly up or down depending on his performance.

Game progression and its corresponding dynamic difficulty in an arcade game.

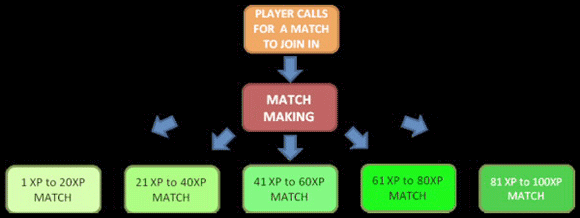

Online competitive games, especially shooters, do the same via matchmaking. Matchmaking software looks for players with a similar level of experience and automatically matches them together. This way, the game is neither too easy nor too difficult, and, as result, players get the best possible game experience.

Matchmaking joins similar experience level player into the same match.

There is also some similarity between "insert another coin to continue", which means progress on coin-op games, and "buy a powerful new weapon" on F2P games, just to take vengeance on a player who is beating you all time.

Both are cheap. With coin-op games, a credit costs around 1 dollar, and with F2P games you can find virtual goods between 50 cents to 6 dollars.

When I was working on coin-op games, I always had the idea that “if the credits were cheaper, the player would spend more money”. It was around the year 2000 when I designed a short coin-op game where each credit would only cost 20 euro cents. The game was an Old West duel game (with two screens and two guns, for two simultaneous players.)

For 20 euro cents, both players would shoot the gun at the same time, one against the other, until one of them died. The surviving player would play the next round for free, and the new player that joined the game would pay the next 20 cent credit (two players per credit).

It was a crazy idea, because movement sensors to detect the player's movement were needed and didn't exist yet. Also, the idea of a short, cheap game was new, too -- plus there was the high cost of the cabinet, so the project was abandoned. These days, it could be possible with the Kinect.

While the game was never made, it illustrates the idea that the right gameplay hook and a cheap entry price could lead people to spend more than the cost of a current generation console game -- and that's what is currently happening in all kinds of F2P games.

Both are impulsive. Imagine you are playing a racing coin-op game. You are about to cross the goal and get time extended, but you don't have much time to go through, 3... 2... 1... 0! When the game climax is at the max, a "Time Up" message appears on screen... You think, "Oh no, If I only had one more second!" The next message that appears is an invitation: “Continue Playing?” and a countdown, 9...8... 7... As fast as you can, you put your hand into your pocket to grab a coin and insert it before the countdown finishes. That's impulse.

The same happens with F2P shooters. Imagine you are fed up that you keep getting killed by the same player... so you want vengeance at any cost. We can be assured that, at the end of the battle, you will be enraged and will enter the shop to buy a more powerful weapon just to kill your rivals.

Both are satisfying to the player. After the coin insertion, which means progress, or after buying a powerful new weapon, which means revenge, the player gets a feeling of satisfaction, as he instantly gets what he wants and needs. And that's good, because playing our game makes the player feel better. That helps us fulfill our desire of keeping the player playing and, therefore, spending money.

Coin-op and F2P games also have similar beta testing phases.

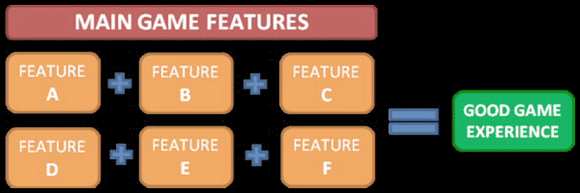

All main features in the game lead to a good game experience, so the player keeps playing.

You have to keep in mind above all that, when beta testing a game, almost all game features must be in. If you test a game that's missing important features, the result you get will be completely different than if you test the same game when it's feature complete.

An example can better explain what I mean:

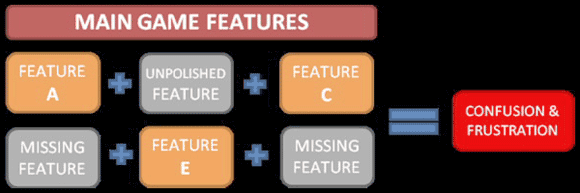

"This shooter game is boring," says the player. "The first 10 minutes are fine, but after a couple of hours playing it becomes repetitive."

Of course it's repetitive and boring! You haven't added the experience-based weapon unlocking system, so progression has no reward. The weapons improvements and weapon add-ons features are not in the game yet, so weapons are not too impressive at the moment.

The awards feature is still missing, so the player doesn't get performance feedback at the end of the match. There are still some unpolished features which can confuse or frustrate the player. The HUD still doesn't give all the information the player needs to have a good game experience. Spawn immunity doesn't have any feedback yet, so the player doesn't know about its existence... And so on.

You can't expect something to be fun when you know there are important missing elements. The game you want to test has to be almost complete, and ready to be tweaked if necessary.

Missing or unpolished features lead to frustration and the player leaving the game.

Normally, with video games, playtests are performed before the game is released. It's important to ensure that all in-game features are clear and players understand the gameplay. After beta testing is done, and once you have players' feedback, the final tweaks can be done. Then, the game can be considered finished. If you think it's necessary, you can organize another focus group just to ensure the game will provide perfect gameplay.

With coin-op games, we beta tested our games by placing a cabinet in a selected arcade for a few weeks. As I said before, you cannot beta test a game which is not almost feature complete, or not polished enough -- otherwise it can create confusion or frustration. In that case, players will simply stop playing the game and the cabinet won't get much traffic. If this happens, the solution is not too difficult: just tweak the game, and look for another arcade to attempt a new beta test.

With F2P games, beta testing conditions are similar to coin-op games, but you have to take into account that now the arcade is the entire world -- so you can't go looking for another world if you mess up your test. Well, you can limit the number of beta testers, but you only have one real opportunity to beta test the game before opening it to the entire world.

If the audience does not like the game (keeping in mind what I said about the quality of the first play experience), players will leave the game. And for the players who don't leave, making big changes can be dangerous, because people can easily react in a bad way to these changes -- just because the game is different than what they are used to, even if the changes you've applied have been good.

The most valuable information from the beta test phase is the player's first impression of the game. After the first week of play, people get used to playing your game, and, even without realizing it, they skip or avoid those uncomfortable or unfavorable situations. We said that the player gets "intoxicated" by the game, and, therefore, the results you get after a week get also "intoxicated". Remember, the most valuable info is always the first impression.

This article is just some thoughts based on my past experiences in the games industry. They were real sensations I had during the production of Freak Wars: Torrente Online 2, as I was constantly having deja vu moments of my splendid days working at Gaelco.

This article probably misses some similarities between these two types of games, and even similarities with other game types I didn't refer to, but maybe you can think of some and add them to the comments!

Special thanks to Abel Bascuñana for his guidance and help.

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like