Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

In this bonus Gamasutra design article, academic Tolino introduces his own classification for player-generated content, explaining what makes game player-created content special -- from new levels through cosplay, glitching, and beyond.

[In this bonus Gamasutra design article, academic Tolino introduces his own classification for player-generated content, explaining what makes game player-created content special -- from new levels through cosplay, glitching, and beyond.]

In October 2007, Valve released the video game Portal. The game was a huge success and was praised for its innovative game play and stunning atmosphere. Throughout Portal, a computer named GLaDOS directs the players and repeatedly promises a cake to those who succeed.

Shortly after the game's release, Portal players, inspired by the game, began posting photos of cakes (link) they had baked using an original recipe hidden in an "Easter egg" within the game. In June 2006, a video was posted on YouTube in which a person is dressed as a block from the classic video game, Tetris (link).

In the video, the person runs around in a city and tries to fit the block costume into the corners of houses and different objects, as if performing a real-life game of Tetris. In both of these examples, players used elements of the video game to create their own projects. How can these player-created phenomena be explained and classified for the benefit of game designers?

The player-baked cakes and the real-life Tetris game are examples of "ludic artifacts," player-created objects (e.g. videos or costumes) inspired by video games and posted on the internet. Analyzing these ludic artifacts can be useful for game designers, and this article will present a model for better understanding player-created content and the motivation for players to creatively expand on their gaming experience. This article will also discuss methods for designing games in a way which encourages players to not only play the game, but to transcend the video game itself and invent their own game-based creations.

First, it is important to understand what ludic artifacts are, or more importantly, what they are not. In many video games, such as Unreal Tournament or LittleBigPlanet, players are given the opportunity to create custom levels or maps. These maps, and all other forms of game content, are not considered ludic artifacts. They are confined to the game and can be described as "user-generated game content."

In contrast to that, the experience of playing a game can of course lead to the creation of ludic artifacts. A player who completes all levels of Half-Life in 45 minutes and records a video of the impressive feat could decide to share his run and distribute it over the internet. Hereto, the architecture of the game world and the player's gameplay is transformed into a ludic artifact.

The clear distinction between user-generated game content and ludic artifacts then is the location or use of the content ("non-trivial" use), ludic artifacts being generated or used "outside" the confines of the game itself. Other examples of ludic artifacts include game-related graffiti, reenactments of game scenes, costumes inspired by game characters, paper reproductions of game objects, maps of game locations, video documentation of game glitches, machinima films and music videos, comics made with the help of game engines, in-game performances and even game-related Wikipedia sites (Examples).

All these artifacts may seem to have little in common, but an in-depth study of ludic artifacts, their differences, and, more importantly, their similarities, reveals their ability to be categorized and explained. The findings of this study are especially relevant for game developers, for whom it is important to incorporate basic principles of user-generated content into their game design process.

With these basic principles in mind, the design of games would not only focus on the perfection of the gameplay itself. In addition, the game design would focus on the motivation of the players to generate their own media products by transcending the borders of these games. This would strengthen the game's community and increase the lifecycle of the game -- as well as its popularity.

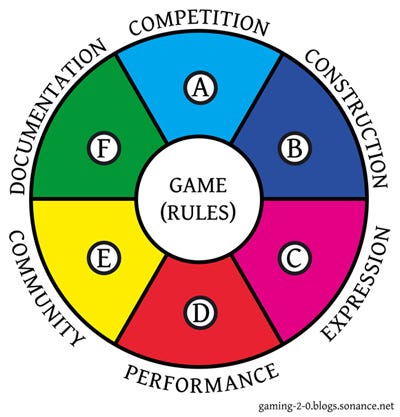

The questions we need to answer are, how can different ludic artifacts be described and the motivation to create them be explained, so that game-designers can incorporate this knowledge into their work? To understand ludic artifacts and map them into an understandable diagram, we need a classification, a taxonomy of ludic artifacts. Some of the artifacts created are videos, while others are drawings or even edibles. To categorize by the numerous product types (e.g. "videos" or "objects") would make comparison difficult, but a broader scope shows that artifacts can be organized easily according to motivation, into the following six categories:

A. Competition

B. Construction

C. Expression

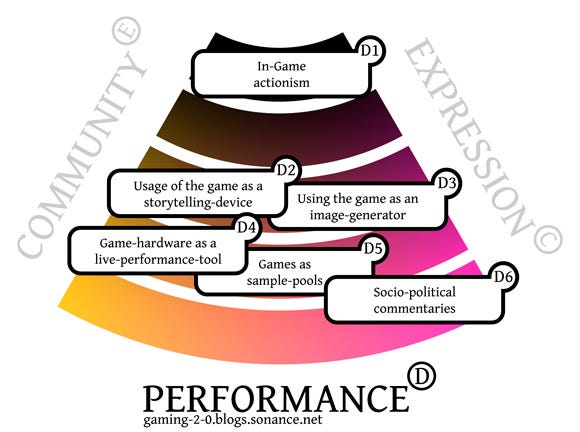

D. Performance

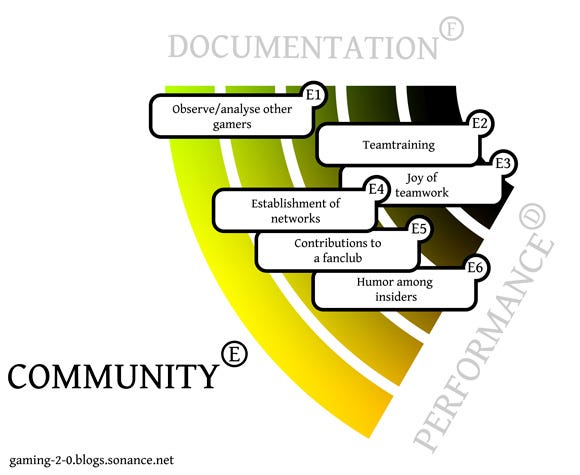

E. Community

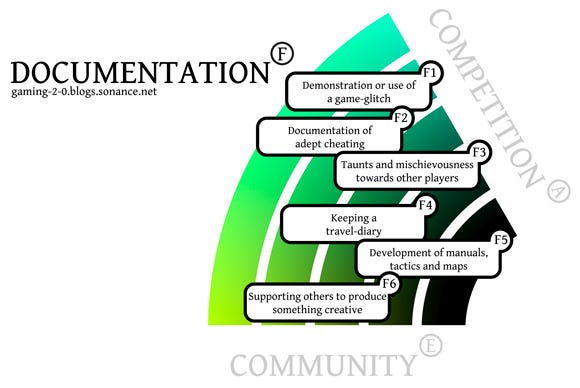

F. Documentation

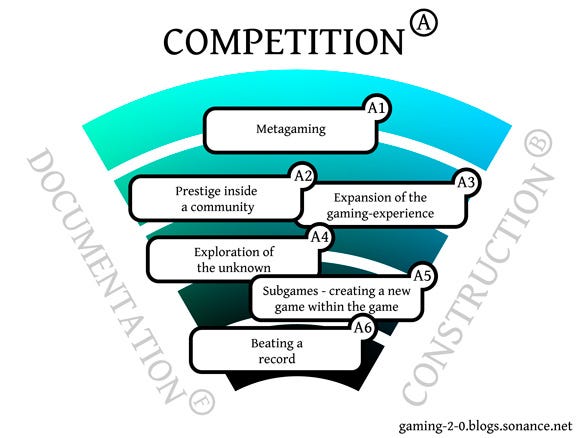

The first of six categories of motivation is Competition, and includes all ludic artifacts created out of a motivation to compete with other players, or against a computer. Ludic artifacts which aim to break or set records, such as "speed runs" (Example), or which compare game results with others fall into this category.

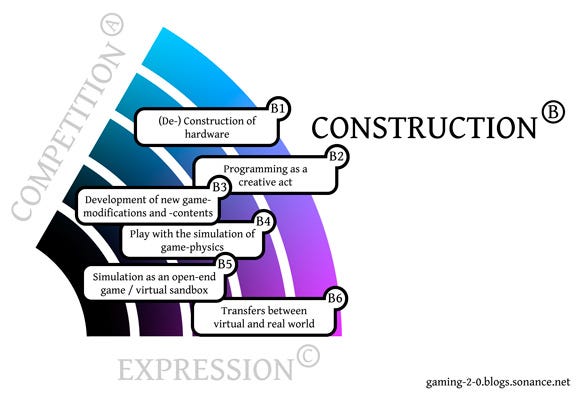

Construction is the category, which includes all real-life ludic artifacts, or objects created by players based on an element of the game. Tangible objects, such as portal guns like those in Portal (Link), but also virtual objects, like a set for a machinima film in a level editor, are included in the Construction category.

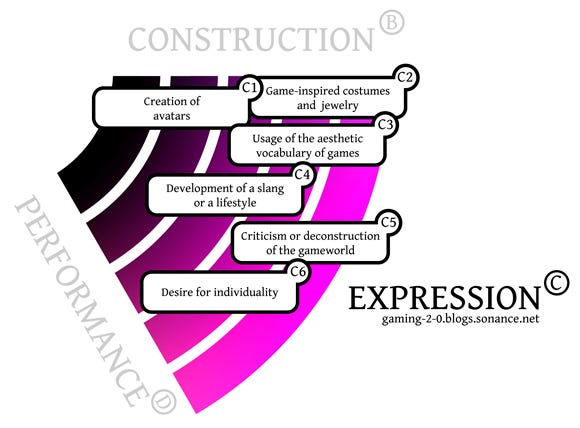

Expression refers to all ludic artifacts through which players seek to express their own personality or moods. Many gamers create objects from games for costume play (known as "cosplay") or as everyday fashion. Expression artifacts aim to underline the individuality of their creator (Example).

The fourth category, Performance, explains all ludic artifacts in which the player uses the game for any kind of performance. Game Boys can be used as sound generators in audio performances, visual material from games can be used for live visuals, or game engines could be used to make machinima films or narrate a story (Example).

Community includes all ludic artifacts with the purpose of strengthening or supporting a community of players. Networking among players, training and support of other gamers or the benefits of a belonging to a group and sharing its humor are motivations explained by the Community category (Example).

The sixth and last category, Documentation, includes all ludic artifacts that aim to track, detail, or guide something. Diaries, details about the game character's adventures, maps, tactic guides, walk-troughs, and documentation of glitches are included under Documentation (Example).

This basic, six-category taxonomy enables us to discuss ludic artifacts more easily, and makes it easier to distinguish between the motivations behind their creation. Going further, we can arrange these categories on a diagram like the one shown above, and use the two orientations of the concentric circles to map the ludic artifacts with more detail and meaning.

A more complex, second-order model for comparing ludic artifacts places the six basic categories on the ring-diagram in a way that their position tells us something about their relation to the whole diagram. This second order is in addition to the basic six categories and includes two new directions, "immersion" and "transcend." Our diagram now includes two axes. Artifacts belonging to one of the six original categories move along the circle, and towards the center according to their content.

For example, an artifact, which possesses Expression attributes and is also related to Performance lies between the fields Expression and Performance and would be placed between these two. However, the subcategories have different distances from the center of the diagram. Thus, the closer subcategories are placed to center of the circle, the more the generated ludic artifacts are "following the rules of the game". The further the subcategories are placed away from the center of the circle, the more the ludic artifact is trying to "transcend the game."

For example, a hand-drawn map of a dungeon would support the game, or help other players, and therefore be positioned close to the center of the circle. On the other hand, a player could create a sword inspired by the game and take it to a convention. In this case the sword is quite far from being played or used for the game itself, so the ludic artifact would be positioned quite far away from the center.

The examination of many case studies and ludic artifacts has shown that almost any ludic artifact can be mapped onto this taxonomy. In addition, for every basic category, six subcategories can be found and described, for a total taxonomy of 36 subcategories. The taxonomy of each subcategory consists of a letter and a number, wherein the letter stands for the main category, and the number stands for the subcategory. In the case of the subcategory "beating a record" (A6) for example, the category "Competition" is classified as "A" and the number "6" describes the subcategory. To describe each one of these 36 subcategories would go beyond the scope of this article, so instead I will focus on the subcategories that are most interesting and relevant for game designers.

(click image for full size)

From a game designer's point of view, the categorization "A5 -- Subgames -- Creating a Game within a Game," for example, is a useful tool to start examining ludic artifacts, such as the subgame "Cat and Mouse" within the game Project Gotham Racing 3. With "Cat and Mouse," players developed their own set of rules without changing the rules of the main game.

First, players divide into two teams, and in each team, one player must drive a very slow car. The teammates of the slower car must constantly ram the slow car, and the team who manages to push its own slow car over the finishing line first wins. The "Cat and Mouse" subgame even has its own Wikipedia entry (Link).

Even within a game with a fixed set of rules, multiple subgames are possible. Therefore, game designers could analyze their games before release and suggest various subgames to players without altering the original game at all. Game variants could be explained via text in a submenu of the game.

Another interesting ludic artifact from a game designer's point of view could be the category A6 - Beating a record. Many games are divided into levels, and when finishing a level, players have the opportunity to view a summary of their performance. Let's take the first version of Doom as an example. After finishing a single map, the player is shown a short summary, including percentage of monsters killed, percentage of secrets found, and most interestingly, a par time (Screenshot).

While most players do not manage to play the levels of Doom in par time on the first run, this little number can be very motivating to players to play the level again and again. This type of feedback at the end of a level can be extended to many other actions in the gameplay. Bearing these motivating factors in mind, and without changing the game engine, game designers can develop record sets for various game actions. By doing so, game designers can inspire and motivate players to generate ludic artifacts from their gameplay, and to share these artifacts with other players.

The second main category, Construction, also explains many motivations for ludic artifacts, which can be relevant when designing games. For example, Category B4 is called "Play with the simulation of game-physics," and many modern 3D games incorporate some kind of physics simulation into gameplay.

For the game Half-Life 2 a modification called "Garry's Mod" is available (Link). The modification to the original game makes it possible for users to edit the contents of the game: all objects of the game can be imported and the gamer is enabled to alter the physics of the game world. Some gamers even constructed very complex Rube-Goldberg machines and made videos of the machines' complex physical interactions (Example).

For game designers, it would be possible to incorporate "free form editors," in which all components of the game could be used, not only for constructing levels, but also for creating sets for machinima movies or other applications game designers can't even imagine. In the case of Half-Life 2, the release of Garry's Mod resulted in a large variety of comic strips being produced (Example). With Garry's Mod, players were able to use the game to pose puppets, and screenshots of the posed scenes were altered in Photoshop and transformed into comics.

The third category, Expression, also offers many opportunities for game designers to examine ludic artifacts. The subcategory C2 -- "Game-inspired Costumes and Jewelry" is closely connected to the category B6 -- "Transfers between Virtual and Real." The basic motivation behind both categories is the player's interest in realizing virtual objects (Example).

Ludic artifacts in these two categories often include objects from a game, which are reproduced out of simple materials and geometric shapes, which are easy for players to fabricate. Costumes and jewelry based on those of game characters are very popular ludic artifacts, which players can fabricate themselves (Example).

From a game designer's standpoint, it would be easy to provide guidance in the production of such objects. For example, the game's website could provide sewing patterns for game costumes, or PDF files with instructions on how to craft objects out of paper. Paper objects are especially popular among gamers for creating ludic artifacts, because paper is cheap and color printers are widely accessible.

Game language can also help players express their identity and their affiliation to a specific game. During gameplay, players must apply many different skills, including orientation in the vast landscape of a level and the quick combination of keys. Categorization C4 -- "Development of a unique language or slang" describes the phenomenon of players who communicate with other players within a game in a self-made, game-based language, and who teach it to new players.

A prominent, not game-related example could here be the book and movie Clockwork Orange, where the author coined a unique language. The language, "Nadsat" is a mixture between Russian and slang English (Link) and became as popular as the Klingon language from Star Trek. There are few examples of ludic artifacts, where game slang is used to transport a very special kind of humor (Example), but the language used here isn't a specially developed one.

When games that originally come in English language are played in other countries by gamers that have different languages (e.g. German or Italian), in most cases, players continue to use the English terms of the original game (e.g. the term "raid" in World of Warcraft is also used among German-speaking players).

By developing a unique game-slang for a game, this language could transcend language-barriers and support the feeling of unity among players around the world. Players could fulfill their desire for individuality (category C6) and self-expression within and outside of the game, based on this special game-slang.

The Performance category offers many opportunities for game designers to support players in their desire for expression. The subcategory D2 -- "Usage of the Game as a Storytelling Device" defines a game as the basis for the production of machinima films (Example).

The game Battlefield, for instance, has spurred many players to produce machinima movies that are impressively well made. The player group "Snoken" involved up to 64 players to join together simultaneously to produce movies where the roles of each player were exactly planned. Some players acted as cameramen, and others as directors or actors (Videolink). Using Voice over IP, the whole group coordinated to produce the video.

Game designers could support this complex teamwork by making it possible for players to render sequences of gameplay to their local hard drive without the use of external capturing software. The files could then be shared among the team members via a special in-game file browser to transfer the video files among the team players.

Another possibility for game designers could be to offer a pre-designed visual vocabulary of cut scenes apart from the main game storyline, so that players could cut their own version of the game, a tactic which is called "Re-Cut" in cinematography. The goal here is to make it as easy as possible for players to create and share their expressions and performances outside of the game.

Game audio, like the soundtracks from Super Mario or Tetris, offer still more options, like making game soundtracks available to artists in high quality and in loops (D5 -- "games as sample-pools") for easy integration into remixes and DJ live sets. Websites devoted to the soundtracks of retro games from the Commodore Amiga computer already exist, and there, gamers and audio producers exchange their game based music (Link).

The Community category incorporates ludic artifacts, such as team projects, which demand strong social skills and organization among players. Blizzard and Xfire organized huge machinima contests among World of Warcraft players (Link), giving away large cash prizes for the winners. Convincing gamers to team up and organizing complex projects not only supports the establishment of networks (E4) but also gives players the feeling of being part of a something and unique (E3 -- "joy of teamwork").

But the reward for such prizes must not necessarily be real cash. When rating user-generated videos or audio productions using some kind of voting system, it would also be possible to reward players within the game, with game items or ladder points, for instance. The support of other players could also be rewarded; by creating some kind of tutor mode, players could collect points or credits when they help new players get oriented or learn new tactics in the game world (E2 -- "Teamtraining").

The last category, Documentation, aims to explain the desires of players to document skills, achievements or performances. It can be compared to taking photographs on a journey. The subcategory F4 --"Keeping a Travel Diary" incorporates ludic artifacts because of the player's strong desire to keep memories of his or her achievements within the game.

An opportunity for Documentation exists for players of the game The Sims, since players can share a diary with others, publish screenshots from the game, and keep a diary of social interactions that are going on in that particular game world.

Most games offer a screenshot function, but the user is usually responsible for manually uploading the screenshots to some kind of forum. With an online user account it would be possible to publish screenshots directly from the game onto the net.

There are different approaches to cross social networks and gaming communities (Example) but most of them exist outside of the game. From a game design standpoint, it could be worthwhile to implement these social sharing possibilities into games and make them compatible with web services like Twitter and Facebook, so that the exchange of ludic artifacts from within games is easier for the player.

Another important point is the subcategory F5 -- "Development of Manuals, Tactics and Maps." The desire to discover and reveal something hidden is strong in many players (Example). Since the early days of computer gaming, people have drawn maps of game landscapes and shared their findings with other players. Many of the riddles and mazes in modern computer games are far too easy for the players, and most importantly, not designed for collective intelligence.

Games that are designed to be played with the help of the vast internet community are alternate reality games (ARGs). In such games, players must analyze small clues and then share their findings with others, thereby feeding a Wiki site, for example, organized by the players of the game. Game designers constantly update and expand the hints in the game, and players continuously solve the puzzles through their teamwork and cooperation with other players.

The ARG The Beast was created for promotional reasons for the film Artificial Intelligence: A.I., but turned out to be much more appealing and challenging than the film itself (Link). From a game designer's point of view here it would be possible to connect in-game storytelling and a collective online mission.

This way games could become more challenging. To find the right balance is no easy task, but many players would appreciate and benefit from a transition to more online teamwork beyond the actual gameplay itself.

For game designers, the taxonomy of ludic artifacts also offers a reverse approach to determining player motivations and behaviors. One possibility would be to place points on the empty diagram and then construct possibilities for ludic artifacts by considering the distance to the center and the position of the points between the main fields: competition, construction, expression, performance, community and documentation.

This article aimed to introduce a different approach to the topic "user-generated content" and tried to look beyond the well-known concepts of "machinima" and "gamic." With the taxonomy of ludic artifacts in mind, it is easier for game designers to prepare games for players' game-related creations.

By encouraging players to transcend the game and take gameplay one step further, game designers could attract more players, better satisfy current players, and increase the lifespan of a game.

The taxonomy introduced in this text is the result of a dissertation on the topic of user- generated game artifacts entitled, "Gaming 2.0 -- Computer Games and Cultural Production -- Participation Analysis of Computer Gamers in a Convergent Media Culture and Taxonomy of Ludic Artifacts." The thesis is written in the German language, and the full text is available as PDF file here: http://gaming-2-0.blogs.sonance.net/a-download-gaming-20

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like