Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Gamasutra travels to Jonathan Blow's studio to take a look at The Witness and discuss the development of the game, in a wide-ranging conversation that covers everything from design to business considerations.

[Gamasutra travels to Jonathan Blow's studio to take a look at The Witness and discuss the development of the game, in a wide-ranging conversation that covers everything from design to business considerations.]

Braid. Though it was far from the first title to hit the service, it defined the Xbox Live Arcade game: original, thoughtful, and fundamentally unlike anything shipped on a disc.

It also defined the dream of the independent developer. It went on to be a tremendous success -- winning awards, moving to other platforms, and in the process of both, selling so many copies that developer Jonathan Blow has been able to assemble a small team to pursue the multi-year development of his latest title, The Witness.

The Witness is completely funded (at a budget Blow estimates at 2 million dollars) by Braid's success. It will be finished when Blow says it is, and has no firm target for release, no publisher, and no announced platforms.

Recently, Gamasutra was invited to Blow's new studio in Berkeley, California to play The Witness (on a Windows PC) and speak with Blow about development of the game.

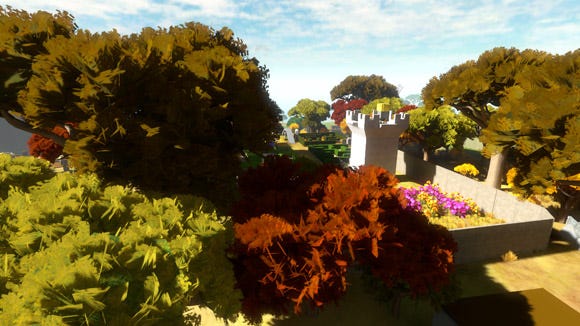

Unlike Braid, The Witness is a 3D adventure game, though it shares with its predecessor a fixation on challenging puzzles. It's also already -- even though it's far from finished -- quite atmospheric, a quality Blow says is "important" to him.

The game begins in a small room. A locked door has a blue panel on it; to open it, you solve a very simple puzzle by tracing a white line across the panel. Exit into a yard behind the building, and you'll have to solve three more to escape. At this point, the player is confronted with a large island covered in trees, small structures, and puzzle panels of varying complexity, all mazes of white lines on blue panels.

All of the game's puzzles are confined to these panels; you explore the island, where they dot the landscape, and solve them one-by-one. Some unlock doors, others power machinery, and some serve no purpose beyond teaching you how to solve more challenging puzzles. Every structure in The Witness has these panels in, on, or near it.

Changing rules, introduced gradually, force the player to make mental hops from concept to concept, gradually learning to think in different ways. Though the two games are quite different, you can tell that the mind behind Braid designed this game.

Though Blow doesn't like a lot of what the mainstream industry does with games -- as you'll soon read -- he does like how it makes core gameplay clear. It's one thing that he's taking from the FPS genre and applying to his adventure game.

While classic adventure games could be incredibly confusing, unintuitive, and ambiguous, The Witness stays readable. "As soon as you see [a panel], you know what it is," says Blow. "It's like, 'That is a puzzle, I know that. There's no ambiguity. I know that's a puzzle, I know how to solve it in general, I know I'm going to start tracing at one of the circles and go to one of the exits."

All the same, he says, "The point of the game is not really to have puzzles, which is going to sound stupid because this is a game full of puzzles, right? The point -- what the puzzles are about -- is each of these communicates a little thing." When Blow designs the game world, he says, "I actually sit there without necessarily designing puzzles at first; I just explore what the possibilities are. And then the puzzles are ways of illustrating those, or communicating those."

So what led Blow to follow up Braid with The Witness? The ideas for some of the panel puzzles came first, he says. In particular, two, which both have clues in objects that populate the world: apple trees and carved walls. "That was originally the concept for the game, and then I decided, well, I need to build more of a system, instead of a bunch of one-off random stuff." A world began to take shape.

That, then, had a natural consequence, says Blow: build a world, and you need more puzzles. "Eventually, I started adding the more logic-oriented puzzles too, and it makes a pretty interesting dichotomy between things. And the fact that it's located on an island -- it's just one of those things I knew as soon as I thought of the game. It just makes sense, in a lot of ways," he says.

The background of the character the player inhabits is unclear. The story is filled in by recordings in much the same style as BioShock's audio logs. A friendly-sounding narrator tells the player that it's natural that they don't remember coming to the island -- but not to fear, as they chose to be here.

The game is designed so that "there's just a great deal of freedom" for the player, says Blow. Players can choose to doggedly solve clusters of puzzles, walk around sampling the island in any order they choose, or the "whole spectrum in between that," says Blow. It's the same kind of freedom to pick and choose which players had in Braid, but in full 3D.

Says Blow, "It's just interesting to give players that choice. There's narrative stuff happening, but I don't know what order the player is going to listen to it in. Constructing something made for that level of freedom is actually a little bit challenging."

Most 3D games offer a "a tightly-controlled linear experience", says Blow, giving him few cues on how to design something that can be played in any order. "And so you have to abandon the influence of so many games in order to get back to a head space where it's like, 'No, let's just do something that makes sense in this kind of structure,'" he says.

While just about everybody has compared the game to Myst based on how it looks, there's a crucial difference between The Witness and the adventure games of old.

"With adventure games, [there's] this idea that you have a key/door puzzle. 'I need to go find the key' -- and maybe there's a puzzle to even get the key -- 'and then I can open the door.' So this game has that all over the place, but the key is just in your head," says Blow.

Once players learn the way a puzzle works, and become proficient at solving it, they can simply move on to the next. Most puzzles are freely accessible at any time, and few are gated by anything but the player's own knowledge and skill. Aside from a few locked buildings, the vast majority of the island is accessible from the get-go.

He's also been experimenting with how clear to make things: whether each puzzle should lead the player on to another. The landscape of The Witness is crisscrossed with power cables that you can trace to new destinations.

"My thinking has evolved over time," says Blow. "Originally the power cables were part of that extreme clarity. Like, you solve the panel, and there's not a question of where to go next. But what I've found as I work on the game a little more is that I like if there's some variability. So early in the game we can have a lot of clarity, but then later on maybe some are harder to follow."

Pacing can also be a challenge for him. Early versions of the game "felt grindy" for players, as they solved puzzle after puzzle without break, says Blow. To that end, he's changing the island's structure so that the areas offer clusters of different sorts of things -- exploration, puzzle-solving, and story. "So it's like a little bit of like a scavenger hunt or something, almost, and that's been kind of nice. I like it, actually."

However, he is aware that the "paradox of choice" can set in: "people just get grumpy" when they have no sense of what they should be doing. "But now we've got a lot more trees that sort of cloak areas and stuff, and there's more of a feeling of revealing new parts of the island as you walk around."

What's important to Blow is that players approach the game with a sense of curiosity. "The design of this game makes a great deal of assumption that you actually are going to proceed forward with that kind of game thinking... Because the game doesn't push you into anything."

While the island is interesting to explore, the panel puzzles form the core of The Witness. Generally, these puzzles look simple, but can be surprisingly challenging to solve. "Another fun thing to explore was [how] these things can get kind of hard sometimes, even just with this small number of elements," says Blow.

The early puzzles teach you how they work, and later ones add new elements, such as colored dots that must be separated by the line you trace. "And then on top of that, there's just a layer of ramping difficulty across all these puzzles," says Blow.

As a designer, Blow has become interested in the tension between logic and intuition in puzzle design. One puzzle, in which the player must observe apple trees in the environment, whose branches echo the maze on the panel, is "completely illogical," says Blow, but "nobody has ever, ever failed to get the apple trees, all three of them." That part of the game is "not about logic, it's just about intuition."

Blow's thinking about the game takes the sort of intuitive leaps he hopes the player will. When the player solves a puzzle, "there's that a-ha thing that happens," says Blow. But, he says, "what interests me is not that rush of like, 'Oh, I understand this now,' but it's the thing that the player understands now.

"I guess because of that, my design thought is focused on what's going through the player's head right now... now... now... all the time. And so, that's just kind of the way that I see stuff. And so I'll think about a puzzle. And I'll think about it like, 'Well, okay, when the player sees this -- before they understand what it means -- what are they going to be thinking?'"

Though Blow likes to think he can understand the player's frame of mind, he knows it's "impossible". "I have some ideal player, who I don't know who that is exactly, but it's somebody who likes the kind of games that I like, or something. And so I just think about, 'What would that ideal player do in this situation?' And that guides some decisions sometimes. I don't know. It's really an off-the-cuff kind of process," Blow admits.

He's not worried, however, by getting off-track as the game expands in scope and starts to grow beyond its initial design space. "This game has something in common with Braid, where the design process was first. I go find some interesting things, and then I try to curate them, and illustrate them in the form of these puzzles.

"But the fact that I found those interesting things -- those are there," says Blow, referring to different real-world phenomena, such as the fact that colored glass affects what you see through it. Colored dots shift tone when seen through yellow or blue windows, and an impossible puzzle can suddenly be solved.

"Because that stuff is at the core of the game. That stuff is not bullshit. That's the universe we live in, right? And because of that it's just kind of interesting. As a game designer, sometimes I can do a better job of building a puzzle to illustrate that, and sometimes I can do a worse job. I could build a bad puzzle. Hopefully I don't. Hopefully I catch it, and make it better. But let's suppose I still build bad puzzles. The game is still good, at some level, because it's got that stuff at the core," says Blow.

"This is not about me trying to impress people with my game design. I'm trying to make a really interesting and nice game design, but it's for something. It's utilitarian. It's trying to get at these ideas that are in there."

It's little surprise that Blow doesn't have much time for the design ideas that populate mainstream games these days, given that his game embraces concepts that are increasingly ignored by major studios, such as uncertainty.

"That's one thing that really disheartens me about mainstream games. There's a joy of discovery that is gone from a lot of games," says Blow. "And that gets very tedious to me." The voiceovers in The Witness will never instruct the player on how to solve the game's puzzles.

"Original Nintendo games, like Metroid and stuff, were extremely like, you just had to find your way through that game," he says. "Somehow that turned into 'we focus test the hell out of everything and any time anybody has a single problem with anything, we kind of iron that out.' And I feel like it makes games kind of flat."

Games today often constantly reward the player, or strive to provide novel experience after novel experience. Short attention spans are expected.

"And this is definitely a long attention span game, right? You have to not be playing a game for achievements, or for power ups, right? And that's kind of what interests me as a game designer, is creating experiences where the experience itself is interesting enough that you don't need those other trappings to keep people motivated," says Blow.

"I do think that there's an audience out there who appreciates this kind of thing, that's game-literate, that treats the player as someone who's intelligent, first of all, and who's thoughtful and who wants to have some choices to make."

He's making a game that's slow and thoughtful -- that, in itself, is becoming unusual. Many games concentrate on delivering an excess of stimulus in simple environments, quickly navigated. With The Witness, he says, it's the opposite.

"Just given minimal interactivity -- like, 'Hey, I can move and look around and I have a simple interact button,' -- how much can I do to make everything in the world matter? So that if you notice something is there, or if you notice a tree is shaped in a certain way, or you notice a building is oriented a certain way, that actually matters in this game. And the more that you notice, the more the player can get out of that, right? So it's kind of the anti-FPS that way."

He's considered and discarded the current drive to constantly reward the player. "I almost fell into that trap when I was designing this game," says Blow. "My assumption for this game was going to be, any time there's a sequence of like say three things... you go one, two, three, and then the last one there's a little box that you open, and you get a reward," like a recording or other item to collect. The player has no inventory in the current version of The Witness.

"And thankfully, I questioned that again later, and was like, 'Why am I doing this? I'm doing it because somebody thinks that that's what you need to make a game.' And I'm just like, 'You know, no. That's kind of bullshit. That's not what this game is about.'"

He's not a fan of achievements, either -- in fact, he'd love to not have to implement them in The Witness at all.

"These two games that I've made so far have a lot to do with focusing the player's attention, or creating an atmosphere of focus, and having a very intentional design. The game knows what it's about, and knows what it wants you to do. And when you give somebody a bunch of achievements that they can do, it's like, well, maybe I don't really know what I want you to do," says Blow. "Adding this other stuff just defocuses the game."

Well, PlayStation Network and Xbox Live Arcade require them. "Fuck that, man. That's so stupid."

And it's not just about how achievements can warp the design. "It's trying to be a long attention span game. Creating quiet atmosphere. If you solve a puzzle and it's going to go, 'Bloop! Achievement Unlocked,' it pulls you out of the game. It pulls you out of the mood."

While Blow is considering ways to de-emphasize achievements if the game comes to consoles which require them, he'd rather avoid them entirely. "I'm kind of hoping that I don't have to do achievements, one way or another," says Blow, "but we would like to release on one of those consoles. There's quite an audience there, so we'll have to deal with that when the time comes."

Braid deviated from the mainstream in another way. It was a game with secrets -- things which could only be discovered through careful, experimental play (or, soon after release, watching YouTube, Blow laments.) Few games these days still have secrets, however. It was once a foundation of mainstream game design (think back to Super Mario Bros. and The Legend of Zelda.)

"If you're making a triple-A game and it's very expensive," says Blow, "and you're competing with other games that are also very expensive, so the stakes are very high, every dollar you spend, you want it to be there on the screen, and in the player's face. Because if it isn't, then your game is going to seem like it didn't have as much money spent on it as the other one. And that didn't used to be the case, or didn't used to be the mentality."

This doesn't affect just secrets, but also the fundamental design of the games. "You go to some GDC lectures, and there are talks about, 'Well, we had this big dramatic event happening, and players didn't notice it, so here's how we redesigned the level to ensure that they see the thing that we made happen.'"

Blow doesn't like the contemporary "urge to control the player experience very tightly" much.

Current games are, he says, "all about getting every hour of work there on the screen for every player. And I think you do lose something in that. Like the Castlevania game that has the inverted castle [Symphony of the Night]. That's a huge, giant secret that everybody freaked out about, and it was cool!

"It's not just the budget thing, but it's like there's this idea that every player has to have this certain kind of experience, and if they don't, the game's broken somehow... I don't know how that happened, but that became mainstream design thought."

Another place he deviates from the mainstream is focus testing -- he derides it as "like letting people tell you what the game should be." But he's leery of even playtesting the game, although he has done it.

"Even non-focus testing is very dangerous," he says. "For me, it is very important in a way, because I have some abstract idea of how some puzzle is going to play, but I don't really know if my guess about how that's going to play is correct in reality. So it's a reality check."

But while he's seen players stumble over his puzzles "quite a number of times," he says, "I haven't changed the nature of the game or anything. But the danger -- even if I'm just using it as that reality check -- is that any time anyone has an experience that's even slightly different from my ideal version of what I would want, I'm like, 'Oh, I've got to fix that,' but I think that that's wrong."

When you're too reactive to playtests, says Blow, "You get this totally featureless game out of doing that. No game ever made by man provides a perfect experience to anybody. And attempting to do so can easily -- speaking for me -- carry me away from what's really important about the game. So I try to rein myself in about that."

That said, he hasn't abandoned the idea totally. "It's still something that I'm figuring out. Like, when do you decide to act on something and when do you not? I couldn't exactly tell you what my rule is. I don't know."

It's clear that, given his description of how the very fabric of the game is in flux -- some of the puzzles aren't even hooked up to anything right now, because "we keep moving stuff around the map", the structures are "just kind of plopped in the terrain", and the buildings are, so far, "for the most part, just blocks that I kind of just build in the editor. A few of them are a little more designed" -- Blow has set upon a specific, iterative production process which he believes in.

He says that it's hard to exactly define when The Witness is in "production." He's planning to recruit a few developers later this year, which may mark the beginning of production. But then again, he says, "we're kind of in production now. Sort of. I don't know. We're just doing whatever makes sense."

He looks at the mainstream industry's inflexibility as incompatible with his design sensibility as expressed in Braid and The Witness. "If they think they're being cautious, they'll build a vertical slice. And they'll be like, 'Okay, this is one level of our game, and now let's go into production, and crank it all out.'"

There is no section of The Witness that is yet "done". "I've reworked a lot of these puzzles a number of times, and they get better every time. Because I can't quite see, sometimes, what the best approach to a puzzle is. And sometimes it's like, 'Well, this thing that's up here on the second floor, it needs to be on a ground floor. And the top of this building needs to be open instead of closed. Oh, you know what? It needs to be a totally different shape of building.'"

It's well known that traditional production -- particularly asset generation -- can kill the ability to iterate. "And so for me the quality of this kind of game that I design so far -- this being the second one -- depends a lot on iteration like that. I'll make something and I'll not know how to make it better right now. It's kind of a cool puzzle, but I'm not totally happy with it. And then six months later. I'll wake up one day, and I'll be like, 'You know what? I know exactly how to make that puzzle better,' and I go over and I tweak it, and it's better."

Maintaining momentum on the development, however, is not a problem for Blow, because "there is just a lot to do, and everyone's aware of that," he says.

"I've certainly lost momentum on a lot of projects in my life," Blow admits -- recently among them, mainstream games he has consulted on. "But for me personally it tends to happen when I don't believe enough in what I'm doing. If I think something's really good, I can work on it for quite a long time."

Still, sometimes he does hit creative blocks. "I had a problem with the story. The version of the story that's in the game now is version three, and I was just writing it a couple weeks ago, really, and we recorded it in a rush," he says.

"I feel good about the story now. Like when people play it, and I overhear them playing it, I don't cringe. Whereas I did before, with the first two versions of the story," admits Blow. Given the surprising ambition of the narrative in Braid, the potential pitfalls for The Witness' writing are understandable, too.

"It was sort of a little bit a little bit posture-y, right? Like, this is a game about philosophical stuff, and so here's a recording talking about philosophical stuff. And it just was kind of dreadful. But I didn't think it was going to be kind of dreadful when I wrote it."

Those first recordings Blow got back, however, proved otherwise -- but at first he wasn't sure. "I thought it was just the same kind of thing like, well, nobody likes the way their voice sounds when they record it and play it back. I'm feeling weird about voice actors who are not that good actors, or maybe I'm feeling weird about seeing something I wrote."

It taught him to follow his instincts: "And in reality it was none of that. In reality it was some part of me knew that this story was not right for the game and I was uncomfortable with it, and that was coming to the surface as just this cringing."

So far, The Witness is completely self-funded. "Even if we sign it with a publisher I don't think that we would sign a funding deal," says Blow. He'd be signing only for distribution on platforms where self-publishing is difficult or impossible.

"If we wanted to be on XBLA, we would end up signing with a publisher, but it wouldn't be them giving us money, I don't think. It would be more like, 'Hey look, we've got this game, it's going to be a little bit of free money for you if you sign it,'" he says.

But working with publishers may be difficult for Blow. "I mean, I don't know if that would work out, honestly, because my first rule that I put in the contract is going to say, 'No, you're not allowed to put your publisher splash screen on the front of the game, because I hate that stuff, period.'"

Fortunately, given the success of Braid -- both in terms of the reputation it garnered with gamers and its sales, which have allowed Blow to self-fund -- he's in a good place.

"Compared to Braid, this is a really high budget game. My estimate of the budget for this game is like 2 million dollars, and that's ten times Braid. We're not through development -- you know, games have a way of spiraling out of control. But it's a little bit of a bigger game, so let's say it's a $20 sale price," he says.

"And let's say we get like 70 percent, 60 percent. Then making 2 million dollars is at 150,000 copies -- which is way less than what Braid sold. So even though Braid was at a lower price point -- so it's not a direct comparison -- but you know, it's in that neighborhood, where it doesn't feel super risky," says Blow.

"I guess what I'm trying to say is, the tactic is, 'Yes, spend a bunch to make it good, but don't spend enough that you need to start either doing risky things to make back that amount of money, or needing it to be a hit. Or even that you have this very strong temptation to change the game design to sell it to more people."

This is crucial to Blow, who wants to make sure that he doesn't start making games for the wrong reasons. "I hate the word 'product'," he says, though he's aware that Valve, a developer he respects, uses it internally.

"As an art game company, we're trying to make things that are different from what other people do, and the surest way to make sure that you're not different from other people is to have the same goals as them. And the goal of Activision, or EA, or whatever, is like, 'Well, we're going to sell our game to the maximum number of people.' And the reason their games are the way they are is because they're doing that, and so if we adopt that as our goal, too, then our games are going to start looking a lot like their games."

In the end, then, The Witness is, in many ways, exactly what you'd expect from the man behind Braid. While it's surprising -- even to Blow -- that the game is a 3D adventure in a rich world, peel back the layers and examine the philosophy that underpins it, and you'll find something surprisingly familiar. Play the game and you'll realize that the same mind is once again working on crafting puzzles that look simple but aren't. And he's confident in his creative process, confident in his vision, and clearly confident that he can be successful even if he breaks the rules that so many in the industry assume are inflexible.

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like