American In China: McGee On Making It Work In Shanghai

The ex-id and EA employee speaks out on how developing games in his Shanghai-based studio Spicy Horse has given him a new perspective on development process and teamwork, and whether or not those insights could work in Western studios.

Famous for his work with id Software and on EA-published cult classic Alice, American McGee set up shop in Shanghai, China, in 2007 with his new studio, Spicy Horse. Though the company's first game, Grimm, for the GameTap digital service didn't make a big splash, McGee maintains that developing the game was instrumental in setting up a tightly-run and efficient organization in China, one which has helped him reexamine the very process of developing games.

In fact, McGee suggests that most of what developers know about working in China is wrong. He suggests that process can lead to a crunch-free environment and great quality games -- his team is currently working on a sequel to Alice for EA, for Xbox 360, PlayStation 3, and PC.

Says McGee, "EA has talked about trying to figure out how it is we're doing what we're doing, because clearly they're looking at what we're doing and they're seeing us hit all the milestones and come in ahead of time, and come in high quality, and everything that they could ask for from a development team. [But] I don't know if you could export it."

Here, McGee talks about his short-lived career as an EA hatchet man, the way moving to China has opened his eyes, and some of the points raised in his GDC China presentation, which called for Westerners sent to Shanghai to stop living apart from their Chinese coworkers and get stuck in to the culture to really find success and satisfaction.

You have primarily Western leads right now?

American McGee: Leads-wise it's a mix. Like our tech lead, animation lead, they're both Chinese. The sound department guy is Malaysian. It depends. The lead level designers, some of those guys are Chinese. But then we do have our art director and creative director are both Westerners; they're both Australian actually. And there's no kind of hard and fast rule there.

I was talking to the CCP guys earlier, who are doing that game Dust 514 here. And we started talking about whether you can get to the meeting point, creatively, between Western developers and Eastern developers.

AM: Well, I have yet to figure out how to get to the meeting point between myself and the other Western guys. So I don't even know; the cultural thing doesn't even enter into it. I mean, we get into enough sort of fights; myself and an Australian guy or myself and a British guy. I don't think that the culture thing... not that part of it. I mean, an Australian guy can get into as much of an argument with this as can a Chinese guy about the creative stuff, right?

Yeah. It's interesting to see what things that people in this market, who've grown up with the games here and have a different background, can bring creatively. Have you been seeing that from the Chinese people you've been working with?

AM: Well, yeah. But they're brought up on Western media. I mean, that's one of the ironies of the Chinese gamer -- he's actually playing Western games to a huge degree, but no one's profiting from it.

I mean, when you go into a pirate game store, it's not like the shelves are full up with Chinese boxed product PC games, or Xbox, or PS2. They're playing Western games and they're playing a lot of Western games but it's just that they're not paying anybody.

Nobody back in the West has seen the money from them. I mean, most of the guys in our office, they're playing Western games. They're playing World of Warcraft if they're online. They're playing Call of Duty and Ghostbusters and whatever else. Batman. They're very, very much into those.

So asking them to bring something different, I think it's an issue of cultural expertise, right? They may be better able to bring a snapshot of a game set in China than, say a guy who was raised in Australia might bring one set in Australia. But since we're all consuming the same movies, games, music, for the most part, I think that they would just bring the same kind of cool stuff. A good creative guy's a good creative guy; it doesn't really matter where he's from.

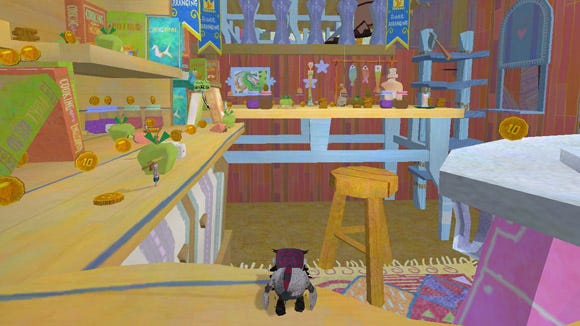

American McGee's Grimm

You discussed the idea of small innovations. Rather than push forward with large things, it's better to do small innovations. What taught you that lesson, or where did that come from as a philosophy?

AM: Well, you understand, it's more about the taking the less risky innovation. It doesn't necessarily mean that we're always doing small ones but when we do a big one, it's one that we're very comfortable with, right? So, we may innovate a lot in terms of an art style but then that's because we're really comfortable with making that new art style.

Whereas we wouldn't take our current [Unreal Engine 3] technology and really build a new engine and try to suddenly start innovating that. I mean, that's what people would call it -- trying to change that to be something that's going to make a big, massive open world game, right?

Which people have done.

AM: They do, but then their heads explode. I mean, you see the teams that do that, they're not a happy lot. And so really the small innovation thing is more about being wise in where we take those risks. It's not to say we don't innovate, or that we only do small things, but it's just being very wise about how we operate.

It makes sense. In fact, I think people don't necessarily figure out the right places to add the personality or add the touch. That's the question, right?

AM: Yeah. I don't know; it's just been a kind of rule that's been with me, I don't know since when. I mean, I think a part of it was when I was at EA, they gave me a job for some time that was to go out and to look at teams that were in trouble...

So I had this job which turned into basically, executioner, because what they were trying to do is ask me to take what I knew about making games and then go and visit these teams that were in trouble, and then work with the teams to try and resolve their problems or kill the team.

It got to a point where when I would come in the door of a studio, guys in the studio would start crying because they knew that I was there to uncover what was wrong, and then kill the team.

And what I saw was, so many times over and over again, decisions made in design, or in the tech, or in creative, that were these giant, unreasonable attempts at some kind of innovation that the technology, or the hardware, or team, or somebody wasn't ready for.

I just saw it so many times, again and again. And a lot of times you'd see what was a good core idea messed up by something like, say 10 years ago, a team trying to make a completely destructible environment.

And you're like, "Guys, give it another 10 years." And even now, 10 years later it's still hard to say anybody has done that, right? But 10 years ago, you'd see guys that set out on a mission to build a game and their core idea was a fully destructible environment.

That's the kind of like innovation for the sake of innovation, but taking too big a bite. And I just saw it too many times; I guess that's where that came from.

How long did you do that at EA?

AM: Until I got really depressed and threatened to quit. It was actually the first thing that I did. They brought me on to work. It was really this weird, mysterious thing. I got flown out, mysteriously, to North Carolina and told that I had to be quiet -- "You can't talk about what you're going to see."

And they walked me in and there was Michael Crichton. Michael Crichton wanted to make a game. They said, "We want you to work with Michael Crichton on this thing." And I signed on to it and I almost immediately started telling EA, "You've got to kill this thing. You can't make this game; it's really bad."

And so I fought so hard to get my first project killed that they then said, "Wow, you're really good at this." That game subsequently went out and sold one copy, literally. It's called Timeline. They did a really bad movie based on it as well.

It does not ring a bell.

AM: Yeah, so they were like, "Wow, you're quite good at this identifying and killing problem teams." So I think I ended up doing that for maybe six or eight months and then I finally said, "No more." And they were flying me all over the world to do this and I just was like, "I can't, I can't."

Timeline

Wow, that's amazing. What year was that?

AM: Well, I'd left, or been fired from, id. I would've been starting EA [around] 2000...

That's crazy. I could always look up Timeline on GameFAQs...

AM: Oh yeah. It ended up being published by Eidos. It's funny. He's actually got a history of making really bad games that sink developers, Crichton does. But nobody really knows about it. Now he's dead, so I guess we'll never find out. His secret will go to the grave with him. He was an exceptionally cool guy; really nice guy to work with. I felt bad to be the guy that killed the project at EA.

It was just a disaster.

AM: It was really bad. It was really, really bad.

It seems like there still hasn't been a lot of opportunity for outside creatives to come in and really actually capitalize properly on the possibilities of games. Is it because they don't understand the medium, do you think? Or have you not worked with anybody else?

AM: Well, in that instance, there was a sort of basic misunderstanding about what was attractive in an interactive entertainment product, right? But then you've got game creators that struggled with that problem as well. So it's not to say that...

Apparently Steven Spielberg did okay with Boom Blox and maybe had something to do with Medal of Honor. And there are people out there that can bring something of an idea. I wouldn't preclude other entertainment people from being able to make games but...

No, I wouldn't say it's not possible, I just haven't seen it. Even Boom Blox is a limited success given the creative potential, I guess. It's a good game and it sold well. But I can't think of a great really "this is it!" moment for an external creative.

AM: No, I'm sure it'll happen. I mean, I think the tools are getting to be ubiquitous enough and close enough to what Hollywood people understand in terms of building sets.

I would guess also, as younger Hollywood people are more conversant in the medium, they will probably get involved, and it's going to be a lot better fit.

AM: There's something I read, a Chinese saying: "You can make a pig run but it doesn't mean you know what one tastes like." Which is a way of saying anybody can make a pig run away but not everyone can eat one.

It's some weird Chinese way of saying that anybody can watch a movie and kind of think they get how it works but not everybody can sit down and make one. And that same thing goes with films and writing books and whatever. I mean, it's a disappointment.

You often hear developers complaining that management will step in and start making creative decisions, and they don't really get it, and that's a similar situation.

AM: It's true.

Well, one thing you talked about is that you don't crunch, which is exceedingly rare. And how did you arrive at that?

AM: Just process. It's crazy. I mean, I wish more people knew about Grimm, because for us it was a phenomenal success, but because of GameTap and their distribution and monetization model, no one really ever heard of it, and it never made a dime for them, or for us.

But what it did do was build us into a studio capable of really rock solid, on-time production, because we had such unbelievably short timelines. I mean, when I came to China, we signed the deal. The clock started ticking at 12 months from myself, the guy Adam that just walked by, and my art director. So we had three guys. We had to build a team, in China, and get our first episode of this game out 12 months from the day that everything started up.

And that was why I brought up Conway's Law. What it did was, the mandate was 24 episodes, each a half hour in length, going to be released this kind of boom, boom, boom fashion of one every eight weeks. So, I reversed the product requirement into that production structure.

And that's what I saying; it kind of ended up looking like, [what] I later learned, is called "Scrum". But I didn't know what Scrum was, because I was out here. I mean, everybody else was going nuts about Scrum back in the States. It wasn't until one of my Western friends came out mid-way through Grimm and said, "Oh, your production looks like Scrum." I'm like, "What the hell is Scrum?"

But it did something really strange -- again, because of the outsourcing as well -- it made us really break the whole project down into these little chunks. And that was one of the cool things about Grimm, was that we shipped 24 individual games. It wasn't one big game. Each episode was completely standalone, and disconnected from the rest.

So as a result we broke the production into 24 discreet timelines and we broke the team up in this way where these little pods were each attacking, and they were cycling. You would have one group doing the concept to Alpha and another group would take their work and do the Alpha to Beta and another group would take their work and do the Beta to final.

It was very much like a sort of TV production model, of you shoot it, and then you send it to editors, and you go to post. We were doing that exact same thing... and it just worked. And that combined with the outsourcing stuff, and how much planning had to go into that, it just emerged and it was really cool.

I think there's still some argument over how much process can help these situations.

AM: So that's the thing I knew from the States, was people, or really Westerners... I try really hard to avoid any kind of Western or Chinese things... because I don't want to sound like a shithead.

But I'll sound like shithead towards Westerns right now, because I think one of the big differences you get between a Chinese and a Western team is that the Western team, it's not holistic; you get a bunch of individuals. And the individuals have their own agendas, and they have their own ideas about what the game should be, and they're very prone to running off and trying to prove something on their own. The John Wayne way of getting something done.

And so for that type of a team, process is looked at like the enemy, right? People see process as a barrier to doing the John Wayne style of making games and owning something and just going off and doing it.

When you come to China, people latch onto process like nothing I've ever seen before. It's a requirement; it's like it's a necessity. They thirst for it. And so it's done this amazing thing where we've got so addicted to process that, like I said, we end up giving days off because we're so far ahead schedule. And then the sky is blue and I'm like, "Fuck it, go outside and play."

So, it's really worked out. And I've got to say, I'm not sure that if I went back to the States and we tried to apply a lot of what we're doing here there, it would necessarily work. So I think it's something very specific to this location.

That was going to be my next question. Could you fire up a consulting business teaching the American McGee way to do process, and get blue sky days?

AM: I don't know. I really don't know. EA has talked about trying to figure out how it is we're doing what we're doing, because clearly they're looking at what we're doing and they're seeing us hit all the milestones and come in ahead of time, and come in high quality, and everything that they could ask for from a development team.

I don't know if you could export it. I really think that another big part of it is that things are so figuratively blue sky here, that people don't bring with them... I don't know. I think there's a sort of taint in the expectation that older Western developers bring as a virtue of the development culture, of a distrust of management, a distrust of process.

That's why I was saying, "Burn it down." I mean, for me, I burned my life down and moved to China. I just washed it all away; I started over from scratch.

And I think that to try to go back to the West and say, "here's a new way of doing games," you're always going to be dragging along with you all the history that those guys brought. One of the great things about our team is that so many people have never made games in our company. Their first game ever was Grimm.

I mean, think about that. We build a company in China, build a team, and half the guys that were on our team had never made a game before, and we still got the thing done. So I think that freshness and the attitudes have a large part to play in all that.

I have an American friend who was in Japan for some time working on games and then he moved. He's now in North America working on a title. And he said that one thing he really liked about Japan was that he would go to people who were below him on the food chain and tell them, "This is what has to get done, please do it." And they would do it.

But in the West, people have to weigh in before they'll do anything. And while he appreciates that creative tension that you get out of the weighing process, that sometimes he would just like people to just do it.

AM: I totally agree. We don't get that automatic resistance here. The team, they've really bought into the process; they trust the process. They saw it work the first time around. I mean, honestly we had a couple times where during Grimm there were people who kind of doubted, and they worried, was it going to work or not?

Once we nailed that, now everybody in the company is like, "Yeah, this fucking works." And like this [national] holiday, we just gave them off a day on each end of the holiday as testament to that. They see it; they go home and tell their families, "This is great, I work eight hours a day, five days a week. I never work on the weekends."

That means that they're actually invested in the process because they know so long as they continue to work with it, they don't have to crunch. So they're all really bought in.

Is there a lot of crunch in Chinese studios typically, the way there is in the West?

AM: Oh yeah. That's the thing is we hear people coming from -- I won't name their names -- but the other big Western studios and publishers out here, the other Chinese big operation houses where they're building MMOs and stuff like that.

They're all working ridiculous hours, just like you do in the West. They're all working crunch, overtime, weekends, you name it. And in the West, before, in California, before there was that ea_spouse situation. I mean, the employers here take advantage of it.

They hire somebody for 40- or whatever-hour work week and then they get 60 to 80 hours out of them and they don't compensate them any more for it. Actually China, they're trying to crack down on labor laws and that stuff now. But it's a similar abuse. You get people who are passionate of games and then you take advantage of them.

So that's one of the reasons why I had on that slide "development paradise". You literally had people come to the studios for interviews and say, "I don't care if you pay me more money. I don't care if you give me a higher title. I just want to come because all of my friends that work here tell me this is development paradise." And that's just awesome.

Do you want to integrate more Western talent in the studio? How do you see it?

AM: There's no plan. I mean it's not like we think there's a magic... it's not about the ratio. It's about the individuals, right? We entertain the idea of hiring anybody, but if you're a Westerner who's coming to work in China for us, we immediately set the expectation that we're a Chinese company.

We pay a Chinese salary. I tell a lot of these guys coming in that they should understand that there are some guys in the company that are really senior Chinese guys that I pay more money then I pay myself on a monthly basis. These Westerners are coming in and saying, "Well I worked on Call of Duty, you should pay me a huge amount of money every month because I'm worth it." And I say to them, "Dude, you're in China!"

I'm in China too. I actually see the importance in keeping the balance, to the degree that I'm willing to sacrifice of my own salary so those Chinese employees in the company know we're not out here just to take advantage of them. It's a really big deal. Actually, when we were inside just now, one guy walked up to me and said, "How do you do it?"

Because he was saying he does what all the other Western companies do: they keep two separate pay scales. They get ex-pats out here they pay some exorbitant amount of money, because this is considered a hardship post by most Western big corporations. Then they keep their Chinese salaries down here. [gestures low] Of course the Chinese guys find out. And what happens? They go, "Fuck you! You're getting paid all the money. You do all the work!" So it doesn't work.

You talked about how personal you are with all your employees, learning their stories and everything. Here's my question: the benefits of that are obvious, but I sat there wondering if you would have the same attitude if you were still an American developer in American development studio. Would you sit down and talk to everyone?

AM: I don't know, but I can tell you that part of what drove that when I got here was finally having the realization that I was out of my place. I was out of my comfort zone. I was really in a strange place. And realizing that what I was investing in was people, the people that are working inside the company.

That was the only thing that was going to work for me in China. And that's what started to drive me to really dig into the who and the what, the how and the why these people joined the company. I don't know. It just happened naturally.

I can say part of it was curiosity and fear that I don't necessarily know if I would have experienced in the States. Because in the States you kind of sense: "Look, I know who you are just by looking at you." But here, as a foreigner, you don't immediately pick up on who someone is by just looking at them.

That's what I was feeling. On one hand you have the cultural curiosity, coming here as an American, to get some insight, right? And also, in America, you're right. When you meet people you very quickly size someone up, I think.

AM: That's right.

Especially other gamers and other game industry people. You talk to them for five minutes and you think you know what they're about.

AM: That's right. I think that's a fallacy as well. We often times make that mistake about people, and that's something that I actually was learning back in the States. I was learning it in large part because a lot of people would make assumptions about me, who I was and what I was about. I tried to turn that around by getting to know people better.

By the I time I came out here, it really became a necessity, because you don't get those immediate cues, and you really have to spend more time to know people.

I find it interesting that you talked about how people expect you to have a whole bunch of slides about how to learn to work in China, and "Here's my breakdown of what you need to know." But your breakdown was more like, "Go live in China, and learn how to live in China, and you'll figure it out."

AM: Exactly. I don't think that the lessons I learned can be taught in a book, because it's a very individual, personal thing. I've seen people come out here that maybe last a month and they freak out. Their brain crashes and they have to flee, and run back home.

This came out of the early version of the talk because I was thinking I was going to highlight cultural differences. I was going to talk about the differences in the cognitive mechanics that go into why we decide to do act in certain ways. And some of the research I was doing in these books, the guys were talking about this. They had these formal scientific studies to back up why they could say that the thought processes were different between the two cultures.

But one of those books, as I was reading through it -- and I kept sensing that this wasn't the right thing to talk about -- one of the guys said that there was this study about Japanese people going to live in the U.S., and the U.S. people going to live in Japan, that said that after they've been there for some time they would take all the mannerisms and behaviors of those cultures. And when I read that, that's when I realized that's really the key.

And if you come out to China with a big long list of all of the things to watch out for and avoid and, "here's what you should expect from China," you've screwed it up right there, because you have all of these expectations on your list, in your pocket, and you're going to subscribe to that and be like, "Oh, he's behaving that way because of X."

When in fact when you sit down with him and say, "Are you being all quiet and not coming to work on time because this book says it's because of this?" And in fact he'll say, "No, actually my daughter is sick." Or, "No, actually that Western designer pissed me off, because he asked me to do something without following the process."

There's a story behind it all. And when you've got that list, it's an excuse to not ask what any of the questions about it are. That is why I was just, "Forget this. Throw it out the window."

Read more about:

FeaturesAbout the Author(s)

You May Also Like

.jpeg?width=700&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)