Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

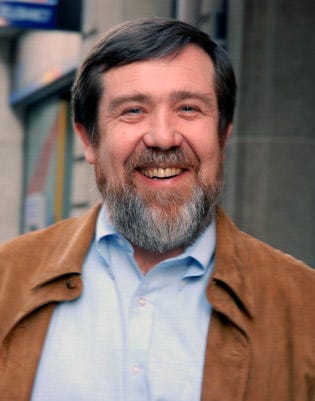

The original creator of Tetris looks back on the game's original creation and ahead to the future of game design, envisioning a world where technology and creativity fuse to exceed the current bounds of today's video game market.

Alexey Pajitnov is, of course, the creator of Tetris -- a game he originally developed while working at the Academy of Sciences in Moscow in 1985. Of course, during the late '80s the game's popularity exploded internationally. It essentially founded the casual puzzle genre thanks to its appeal to a very wide audience, and made dropping-block puzzles a staple of game design.

These days, Pajitnov is not just one of the principles of The Tetris Company, which manages the rights to the game in its many current incarnations; he's also still an active developer, as he discusses in this interview, working on a new multiplayer iteration of Tetris that's been underway for over 10 years.

Gamasutra spoke to Pajitnov at the conclusion of the game's 25th anniversary festivities, and discussed with him his current views on the industry, his memories of the game's initial development, and what he's currently working on. This interview touches on everything from basic tenets of multiplayer design to the potential future of the game industry -- as per Pajitnov's vision.

The 25th anniversary of Tetris is coming to a close.

Alexey Pajitnov: Yes. Yes.

You can't have anticipated the celebration of the 25th anniversary of Tetris when you were originally working on it, I'm sure.

AP: [laughs] Absolutely not!

We're all familiar with the story of you sort of working on it in the then-Soviet Union as a personal project. There was no anticipation that it would even be a commercial product, when you first started it, right?

AP: Exactly, yes. Well, when the game started just breeding, you know, the very first version, the very first prototype, I did realize that it might be a very good game because it was very addictive even in the early stage, but I never could have imagined anything like the history it actually had.

At that time, while there were a lot of home computers in the West, there weren't really home computers in the USSR, were there? Not for average people.

AP: Not really. That's right. All the computers were used mainly for scientific and research [purposes]. They weren't even seriously used in any commercial purposes.

And the computers that you used at the time, were they imported from the West? Or were they homegrown technology?

AP: Actually both. We had several kinds of Russian-produced computers, and I used to work on them. But my computer server was one of a small number of not-secret organizations because it was Academy of Science. That's why many of Western kind of companies just exchanged with us, with hardware as well. So, basically, we did see some Western computers as well.

When you were originally working on Tetris, what kind of computer was it that you used to produce the first version?

AP: It was Russian computer called Elektronika 60. It was a clone of LSI-11computer like PDP-11. It was kind of a mini machine. [laughs] It was very ancient, and it didn't have any graphics on the screen, just letters and numbers.

It's interesting the whole story about how Tetris came out in the West, it was very convoluted at the time as well, the original releases. We've spoken to Henk Rogers recently, and everyone knows the history there, but it was quite an interesting process.

It's interesting the whole story about how Tetris came out in the West, it was very convoluted at the time as well, the original releases. We've spoken to Henk Rogers recently, and everyone knows the history there, but it was quite an interesting process.

AP: Yes. That was fun.

It's not just that it was a game that was very good for the time; it was foundational. It defined a genre. It defined a new genre, which is something that game developers have struggled with. Even at the time, when the medium was more ripe for exploration, it was still hard to define that new way of looking at gameplay.

AP: Yes. Well, most of the games which were popular at that time were like was like mostly like a kid-ish game with animated characters like Pac-Man or Q*bert. Tetris was obviously appealing to everybody, not just for children.

Did you have any access to other Western games on the computers that you had there? Were you able to play things?

AP: I had seen them and tried them, but they weren't available for me for all time, you know. At that time I didn't work on PC; I could just come to my colleagues and ask to look at them, but it wasn't in my possession.

Were you actually interested in games as such as something to move forward in at the time, or were you just doing this just because you had the idea?

AP: Well, I was very interested in games. I liked to play every game. I like board games and everything. Tetris wasn't my first game, I wrote several other puzzles at that time. They weren't very interesting, but I did it. So, basically, yes, I did have a certain interest in games at that time.

Whatever happened to the predecessors to Tetris? Do they still exist, or are they lost?

AP: Well, I did publish a couple of them later, something based on those early prototypes. But most of them were lost, of course. In my profession, as I became a game designer after that, it's about no more than 15 percent of your original ideas came to even the project, you know. As far as product is concerned, I think it's about 10 percent, so it's kind of natural.

Do you find that that's still the case? What are you working on today that you can talk about?

AP: I have a couple... I do a couple of projects just for my own kind of fun, but they are really slow and in the very early stage. But mainly, I am working on next Tetris versions.

So, you still actively work on the Tetris property at this stage?

AP: I can't say it's very actively, but yes, I do spend some time on versions. First of all, we need to approve of the versions which we license out. So, that's part of the job. I need some time to review the versions.

And basically, while we have some discussions on "what should we do next?" and "what is important for Tetris next?" I am not involved in any real projects in development, but strategically, yes, I am involved.

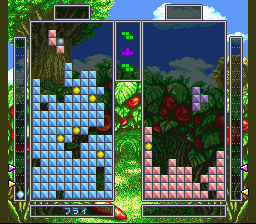

One of the things about Tetris that I think is really interesting is that once it became popular, all the companies that had the rights to it started creating evolutions of it. So, if you look back to the early '90s, you'll have things like Nintendo had Tetris 2, which wasn't really Tetris. One of my favorites is the really obscure Tetris Battle Gaiden for the Japanese Super Famicom.

AP: That was a wonderful game. Yeah, I really loved it.

Did you find it interesting when you started to see these evolutions of Tetris, building on your ideas and coming out? Was that surprising?

Did you find it interesting when you started to see these evolutions of Tetris, building on your ideas and coming out? Was that surprising?

AP: Oh, absolutely. Besides those, I saw lots of pirate versions and lots of kind of amateur versions. Some of them had some kind of promising ideas inside, but I don't know... Unfortunately, none of those versions come close to the original. I don't know what the reasons were. [laughs]

That's something really hard in general -- when a game is simple but deep. To add onto that foundation, I think, is really hard. I think it's something difficult with the puzzle genre in general, even when the original creators are working with their own game, if you look at sequels to puzzle games.

AP: Yeah. Usually, it's really hard to seriously improve an original idea, but that's the phenomena which are hard to explain. But yes. That's what happened. But I think in other genres, like in movies, I could barely remember a good sequel to a good original movie, as well.

I think with more complicated games, it's a lot easier to make a sequel because you've got a lot more elements to work with. I mean, look at what PopCap does what Bejeweled.

AP: Well, I don't know how, but the very original version was demonstrated a brilliant idea of the game, but it had really bad implementation. So, I really enjoy the later implementation of Bejeweled. They had really good improvement, but they didn't improve the original concept, of course.

I was thinking back to the old versions of Tetris, and the Atari Games one, that arcade one, really capitalized on the Russian theme. You know, and it also had the backwards R, which is supposed to look like Cyrillic. Do you think that the Cold War mentality of the era, right around the softening of the Cold War, do you think that helped the popularity -- that people had an interest in Russia?

AP: Yeah. Yeah, that was kind of a coincidence at that time. The interest in Russia was really high, and the fact that they decorated it in kind of a Russian style really helped to the marketing of the game. But it wasn't essentially... I didn't really care [laughs] what kind of decoration they put on it.

At the time, you didn't have any sort of oversight. Now, you say, you definitely evaluate the versions, but at the same time, you didn't have any control, I'm guessing.

AP: Well, if something was obviously wrong, I could object, but yeah, that's right. I didn't participate in any of those kinds of developments.

Well, I mean, communication was, I'm sure, very hard to get out especially before the actual dissolution of the USSR.

AP: Yes. Yes, but... the version was okay, the design was pretty good, so people... the designers, they liked the game and they did their best for the decoration of it, so most of the time I was satisfied with their work.

I think it's probably because they had a fundamental respect for the game.

AP: Yes. I agree with you. So, generally, I noticed through my career that if the game is good, the concept of the game is good, and if the people who work on it like it, they are doing a really amazing job from their part, and that's how the good games are coming out.

The game industry has changed tremendously since the game was originally released, and we're at the point now where there's a huge proliferation of platforms -- mobile, online, consoles, handhelds. From your perspective as a creator, how do you see the market today?

AP: I am very pleased with what's going on because I love games, and I'm very pleased that human beings are playing much more these days than it was in days of my young years, you know. So, I feel that gaming is much better entertainment that movies, television, and reading because it's really active.

Still, though, the industry is not in a very mature stage, and I'm pretty sure it will be a really great future in the nearest time when the more serious kind of creators will get involved, and more engineering and software achievements will be applied to games. But still, it's tremendous progress with the industry, and it's very pleasant for me to observe it.

When it comes to your personal taste and interest in games, are you mostly interested in puzzle games like Tetris, or do you look at the wide variety of stuff that's out there right now? Because there's a huge range of stuff available.

AP: Well, I'm not very involved in the kind of heavy action games. I never was, so it's not my genre. I'm still in love with all the puzzles and casual games. That's my favorite genre for all the time. I really enjoy what's going on there. But it's very interesting stuff in multiplayer as well. So, finally games start to be a medium which joins people together, which is a very important social role of the game. I'm playing World of Warcraft and enjoy it. [laughs]

Speaking of multiplayer, obviously the original version of Tetris wasn't multiplayer. Other people came up with ways to make Tetris multiplayer through new versions. Some were good, some were not. Did you ever give that thought yourself?

AP: Oh, absolutely. We are working on multiplayer versions for more than 10 years -- I've been trying to design it. I should admit that we are not quite there yet.

It's interesting because it's such a simple game in terms of its mechanics.

AP: Yeah. It was quite a problem with Tetris that... the game is very intense, you know? If you play on the high level -- and that's where you want to play usually. So, you play on the edge of your abilities, in terms of the speed and reaction, and everything. So, you kind of have no brain resources to observe what the other people are doing.

AP: Yeah. That's the kind of measured theoretical problem which we need to resolve with multiplayer Tetris. So, if we lower the intensity of personal game playing, we, a little bit, lower the excitement of the game. But if we keep it at the same level, the players don't have resources to really do some kind of multiplayer actions, to observe, to analyze what's going on in the big picture, and adjust their strategy.

So, we have been seated on this problem for a while; that's the brief description of it. But there are still very promising ways to do it, so the version we have now is pretty good. I mean, when you send the garbage in the multiplayer to the other player, it kind of works.

But unfortunately, my dream would be the game, when you could really see what the other people do and take their gameplay and their achievement and their status in the game really in account. That's what the main joy of a multiplayer game is, in my opinion.

I was reading an interview with David Jaffe, the original creator of God of War, in the new EGM. He's talking about the fact that, while there's a great proliferation of multiplayer games right now -- to simplify what he's saying -- they all tend to be very similar. They only touch one aspect of multiplayer, and there's room to grow. So, I get the sense that you'd like to open up a new avenue, maybe, a new way for people to look at multiplayer, with the mode that you'd like to make.

AP: Exactly, because it should be not the mechanical or formal kind of joy for people in the game; they should really share the joy of the game, and really help each other or really find each other. I mean, not just doing what they do but look at what the opponents do. That's my point.

I think that social games like Facebook are sort of working on that, but I think the interaction is pretty shallow still.

AP: Well, we have no rush, I think. Eventually, we'll move to there. [laughs]

It's not so much about technical limitations as it is about evolution of design, do you think?

AP: Absolutely. Games are much more psychological product rather than technical. I knew it for my entire life. That's what helped me to stay in the industry. [laughs]

[laughs] Now, are you working on this with your own studio? Or is it just you working on it?

AP: Well, for the last five years, I am not engaging in work very intentionally, in staff. I am kind of on early retirement. [laughs] I just do it for my own joy, time to time.

That's kind of cool, though. Does it free you up to do it at your own pace and to sort of just make the logical leaps rather than feel the pressure?

AP: Yes, exactly. That was my goal. For many, many years of intensive work, and finally, I got to that point.

Do you think that having more freedom to explore concepts would allow the evolution of games? Having more time? Usually things are made on a product cycle -- 18 months, typically.

AP: Well, yes. it really liberates your mind and probably... I will be able to come up with something really cool in the future, yes. [laughs]

I have Tetris on my iPhone, and I bought the original Game Boy in 1989 with Tetris. Everyone has bought multiple versions of Tetris in their life, I think, at this point, over the years. It's kind of a must-have.

I have Tetris on my iPhone, and I bought the original Game Boy in 1989 with Tetris. Everyone has bought multiple versions of Tetris in their life, I think, at this point, over the years. It's kind of a must-have.

AP: [laughs] Good! Do you enjoy playing with your finger, without a keyboard?

I like it better with the regular control, honestly, than the touch control.

AP: You're much more safe with your movement.

Well, you know, because you're moving in the cardinal directions.

AP: I feel like the iPhone is a really good version. They did a great job. But I still have some [reservations]. I'm not certain that with my tap, the piece will be turned, you know? [laughs] It was a little bit more slow than when I play with the regular keyboard.

I think we're learning as the iPhone sort of takes off, while the touchscreen interface is great, it's not 100 percent suited to everything.

AP: Well, yes. I feel the version is great. I really enjoy it. But still, if you ask me, what platform I would prefer to play, I'm still on computer.

Not Game Boy?

AP: No, mostly on computer. Game Boy is fine, but you know, I lost it many, many years ago.

I have the DS version as well, so that's kind of the same area. For me, Tetris was always synonymous with the Game Boy. It stayed with it all the time.

AP: I agree, yes.

Do you have a good relationship with Nintendo, still?

AP: Absolutely. Yes. We do, and recently, we had a very good Wii version of Tetris. What's really overwhelming was the different variety of the game, and the core game is very good. So, yes, we're fine.

---

Image of Alexey Pajitnov on page 1 taken from Wikipedia, originally created by Flickr user Eunice Szpillman. Used under Creative Commons license.

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like