Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

An experienced producer at Sony Computer Entertainment Europe shares the secrets he's learned from years of seeing developers fail to learn from the mistakes they've made on projects in the past, and offers suggestions on the key learnings to integrate into your production process.

April 3, 2012

Author: by David Manuel

[Experienced Sony Computer Entertainment Europe producer David Manuel shares the secrets he's learned from years of seeing developers fail to learn from the mistakes they've made on projects in the past, and offers suggestions on the key learnings to integrate into your production process.]

Last year, in Brisbane, Australia, where I used to live, there were the worst floods for over 30 years. And yet over the last few centuries there have been several such floods that have hit the city.

After each flood, there has been a commission to look at ways to mitigate flooding in the future. And yet most of the recommendations are ignored and building continued on the flood plains. This seems to be true with a lot of events around the world -- whether it's floods, fires, or riots. A commission is set up, recommendations are made, and then we shelve it and forget about it until it happens again.

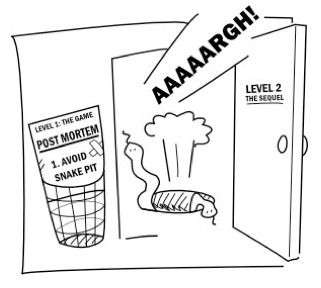

The same thing happens in video game production, too. We often spend time writing up postmortems -- but are these lessons heeded? It's depressing to see the same old issues, such as feature creep, aggressive crunching, low morale, lack of focus and direction, communication issues within the team or/and between developer and publisher, and poor technology and pipelines crop up again and again.

We, as an industry, often fail to act on what we learn.

Over the last decade, we have heard a lot about agile production methodologies and the need to embrace change, which makes sense. However, even when agile is used, similar sorts of problems arise, and in some cases are exacerbated.

The goal of this article is to discuss ways of minimizing these issues at the start of new projects, primarily by creating solid foundations and planning ahead. In other words, even with unpredictable weather, building a dam and avoiding building on flood plains is far cheaper, and better, than waiting for the next flood to hit.

Not all teams write up a postmortem at the end of a project, either due to apathy or because they see no point. However, if we are going to even begin to learn from our mistakes, then all projects, especially the ones which were canned, need to have a postmortem.

It also needs to be a fair process which is diplomatic but at the same time doesn't pull its punches in terms of what went right, what went wrong and what can be improved next time.

Once a postmortem has been written up and agreed by those involved, it needs to be available to all members of the studio -- preferably through the company's intranet, so it can be referenced at any time with ease rather than lost in email or hidden away in archived folders.

When starting a new project, ensure that all relevant recommendations from the postmortem are implemented and checked at regular intervals by the company to avoid these recommendations being forgotten and the same issues constantly recurring.

One of the biggest impacts on finances is managing the peaks and troughs of development team sizes, especially between projects. All too often it appears the next project only really gets going when the current project has ended. Unfortunately, this creates the problem of having too many staff twiddling their thumbs whilst those designing the project are only just beginning to lay down the foundations of the game and its overall vision.

Instead, it would be much better to develop the next game, if possible, well in advance during the current project, with a skeleton crew of staff numbering around 10 percent or so of the eventual team size.

Personally, I would include in that group the following: a full time lead designer to work on the basic vision, research, and game design; a producer to map out the deadlines, the budget, the potential scope, and work closely with the clients on the brief; and a concept artist to visualize initial ideas. Naturally, they would need to regularly liaise with key staff who are due to join the team later -- e.g. the lead programmer and lead artist.

It is also advisable to keep everyone who is earmarked to move onto a new project informed of its progress via presentations, etc. Otherwise, if people are kept in the dark, they may feel resentment or detachment towards the new project. If people are simply slapped onto a project mid-development, they may feel more like a jobbing resource than a valued member of the team.

The idea is that when a number of production staff comes across to work on prototyping, a lot of the foundational work is already in place. Note -- this does not prevent iteration, flexibility or the continuation of creativity at or beyond the concept stage. It is primarily there to initiate what the game and the prototyping should focus on rather than having too many development staff stumbling in the dark looking for ideas without having the luxury of time to research and to simply think. There shouldn't be a massive amount of game development documentation awaiting them at this stage.

The problem with having a lead designer and producer starting early on a new project is that there is a high chance they are also working on another project in mid- or postproduction. To get around this, I would advocate staggering lead designers and producers on projects -- meaning that there would always be an available lead Designer and producer not in full production, even if it's a one project studio. The additional expense would be cost effective, because the rewards are so much greater than the risks.

If we skimp on a resource, particularly one that is needed up front, then the impact can be severe. If you are unsure of someone's ability in a key role at the start, then it will be far more costly to change them later during mid-production, as it is likely their work will be redone.

Make sure you have utmost confidence in those key personnel. If there are any obvious skill shortages, then start the recruitment push with plenty of time to fill the position for when it's needed, or implement a training program.

Whether it's stakeholders within a company and/or external clients such as publishers and licensors, it's vital that those leading a production team meet face-to-face and understand the brief, gain agreement on direction, and establish a working relationship.

This may seem obvious, but many times this doesn't happen early enough, or even at all. We have serious milestones such as Alpha, Beta, and Master with their definitions, and yet there isn't the equivalent early default milestone which includes this. It's kind of assumed it will happen.

How many times are issues caused which can be traced back to poor relationships between companies, initial misunderstandings, and fuzzy starts to production?

I strongly advocate these early face-to-face meetings. I know of a studio who wouldn't allow any of its production staff to fly to meet the licensor because of budgetary travel restrictions. And yet the cost of a few thousand dollars would easily be outweighed by the benefits of saved development work on projects with budgets that run into the millions.

Working with someone you have already met face-to-face -- even just once -- makes a big difference compared to only dealing with them via email and conference calls, as you have a better understanding of them, their mannerisms, and what makes them tick.

It's important that it's the key production staff (particularly the producer) who are working on the project 100 percent meet the stakeholders, and not just those higher up in the development studio. This is so a direct relationship can be formed, and communication is not filtered through a long, inefficient chain of command.

On any team, it is important that the members know their responsibilities and how they fit into the team. Don’t take this for granted, because if a role is vague, then people won’t know what is expected of them, and how the team structure works. Things will get missed, and other roles may be unnecessarily diluted, or even fought over between two people. Identify who’s responsible for the game direction, who’s responsible for line reviews, etc.

During the period of inevitable change that happens when moving from one project to another, it’s best to consult with team members and set up opportunities, as much as can reasonably be expected. If there are any vacancies, have these positions open, so anyone can apply and make their case.

I would also highly recommend implementing 360 degree reviews, where people are able to appraise their peers, those they report to, and those who report to them. This is an excellent way of getting a more rounded picture of the abilities of team members and management, which leads to self-improvement.

Having clarity and structure doesn’t dull initiative and flexibility. Like a football (that is to say, soccer) team, people need to know their role and the expectations that go along with it. Are they a striker and expected to score goals, or a mid-fielder and expected to set up goals?

Of course, a job specification doesn’t capture all the tasks people do, and people will naturally help out above and beyond it -- mid-fielders can also score goals -- but a free-for-all can cause many unnecessary problems.

This is particularly important for stakeholders outside of the team -- senior development management, publishers, licensors, etc. There is a danger of having too many people involved in the approval process, which creates uncertainty about who is responsible for sign off and/or dealing with conflicting feedback. Instead, agree to the roles, the feedback process, and turnaround times at the very start.

At the beginning of a project there are many unknowns, but right from the start there needs to be a long-term plan. Initially, this will be very high-level with key dates -- such as the official start of the project, when pre-dev is due to start, when production begins, Alpha, Beta, and Submission.

At this point, the budget, the milestone dates and the brief for the game need to be established. When the concept of the game has been established, then more things can be estimated. And if dates change -- so can the plan.

It is important that a long-term schedule isn't just an overview knocked up to please the stakeholders and then isn't looked at again until well into production when it has become woefully out of date. It is possible to be agile and to keep an updated long-term plan running alongside. This is particularly important for dependencies, because if features are only looked at milestone by milestone, then key aspects will be missed.

With your stakeholders, formally agree on key milestone definitions -- particularly the early ones such as documentation, end of pre-dev, prototyping, and vertical slice. Now, it might seem a bit odd doing all of this before the design has been finished. But if you know your brief, your budget, your timescale, and overall game idea, then it's possible to do a high-level definition.

For example, if the game is 18 months from start to master, then you may have five months for pre-development. But what can the client expect after five months? Will it be a 100 page Game Design Document? Will it be proof that the gameplay is fun in a grey box prototype, combined with another demo which shows the art style? Will it provide a playable demo that is a vertical slice of the game to a level of final polish in all areas, including art and audio?

The danger I'm trying to highlight in particular is when a team burns many months creating a polished vertical slice, eating into main production time, and causes severe delays. The client may give extensive feedback, and the team then gets caught in a "demo hell".

It is better, instead, to agree with the client what is desirable at the start of pre-production in terms of quality, time, and budget for each section, and for all the production. This sets up reasonable expectations and provides foresight.

Generally, it's best to avoid spending a lot of time and effort developing the first idea that pops into someone's head without looking at the alternative possibilities. It might be a great idea, but there may be better ideas, and without weighing up the alternative possibilities, the weaknesses of one idea may be brushed under the carpet until they become all too apparent -- far into production, when it's too late to change the fundamentals.

At the start, allow any team members and stakeholders to contribute ideas. This is not design by committee, as the design still squarely falls under the responsibility and authority of the lead designer, who should filter these ideas.

This process allows a great deal of buy-in and collaboration from the team. Politically, it is astute to involve the stakeholders -- particularly the client, whether publisher or licensor -- because they are more likely to approve a direction if they were involved in this process.

Sometimes a client might choose not be involved at this level -- however I would recommend that they are presented with a few limited options rather than just one idea for a game direction. This is to avoid a client later going cold on a game direction that they weren't too keen with in the first place. If they demand significant changes later in production, this is likely to cause a lot of problems. Instead, make sure they are involved, excited, and fully onboard.

Imagine sitting a one hour exam where there are six questions which are each worth one sixth of your final grade. It is unlikely you'll spend the first 30 minutes just trying answer the first question. However, in game development, we sometimes spend too long on our preproduction and keep pushing deadlines back to accommodate the slippage. Sometimes we hope we can catch up time later, or we don't even think about the financial impact of missing the ship date, because it's so far away.

This is particularly important for games which are tied into movie releases. If an internal pre-dev deadline continually gets pushed back because the focus is on getting one level polished and complete, then it is likely the rest of the subsequent level design for all the other levels and the polish for the rest of the game will be rushed and suffer.

Adding more time doesn't automatically equate to better quality. We all know of games which have taken an extraordinary amount of time -- primarily due to delays in production -- only to flop because, creatively and technically, they have been surpassed by other games. Being stuck in production doldrums with constant delays and a likely high turnover of staff is a good way to have morale plummet and quality to nosedive.

So whilst it's not always possible to meet deadlines, we do need to be better at hitting them. Along with better planning, one way is to make sure the team is fully aware of the deadline dates. In the past, I have stuck up the dates on the wall and the milestone deliverables on the team wiki, so no one could say they didn't know when Alpha was, etc. It gives everyone a better appreciation of how valuable time is.

Another issue which I find impacts schedules, even at the start of preproduction, is indecision. Whilst pre-dev starts with research, ideas, alternatives etc -- the clock is still ticking away at a constant rate and there needs to be progress on the development of the game. This means key decisions need to be made in a timely fashion. Sometimes trying to get people together to make a relatively straightforward decision can be like herding cats. Decisions can be sat on, deferred, delegated, and forgotten.

However deferring a decision for no apparent good reason can be a worse mistake than making a bad decision. This is not encouraging rash decision-making, but rather after investigating the alternatives and weighing up the pros and cons, having the confidence to make a timely decision and move forward.

Constantly changing decisions is also a type of indecision, which wears down the production team's morale and wastes time. It's important to be flexible, but when decisions are continually reversed, it is counterproductive. Instead, it's better to make the big, high-level decisions, and use these as foundation stones. This is so that as the game progresses, things which have yet to be developed can be changed without altering the fundamentals, unless there is compelling reason to do so, and the impact on the schedules have been looked into.

All the above may seem idealistic, and for certain projects these ideas may well be. However, based on my experience, I believe if we make a conscious effort to strive for better ideals at the start of a project, then this will help us get the game done on time, on budget, and to a high quality. I have seen and have been involved with projects -- even taking into account circumstances outside the studio's control -- where simple decisions taken upstream could have really minimized a lot of pain later.

So whatever methodology a project chooses to use, I would urge that as well as having flexibility, there needs to be a degree of stability. As well as relying on iteration, there needs to be plenty of long-term planning. A producer can put things in place to aid stability and can organize long-term planning. But without the support of the key stakeholders -- especially executives of the developer, the publisher, and the licensor -- it can quickly fall apart. These ideas really need to be embraced by all those involved at the beginning.

In other words, there is no point trying to build a flood defense by yourself if no one gives a damn.

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like