Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Titanic II: Orchestra for Dying at Sea takes players through a journey into the afterlife and the complicated, snarled feelings that surround death.

This interview is part of our Road to the IGF series. The IGF (Independent Games Festival) aims to encourage innovation in game development and to recognize independent game developers advancing the medium. Every year, Game Developer sits down with the finalists for the IGF ahead of GDC to explore the themes, design decisions, and tools behind each entry.

Nominated for the Nuovo Award, Titanic II: Orchestra for Dying at Sea takes players through a journey into the afterlife and the complicated, snarled feelings that surround death.

Game Developer sat down with Flan Falacci, the game's creator, to talk about what they wished to explore in this journey through the afterlife; digging into the connection among horror, wonder, and humor; and the strange process by which playing with fog and background colors lead to this compelling experience.

Who are you, and what was your role in developing Titanic II: Orchestra for Dying At Sea?

My name is Flan! I’m the designer and developer of Titanic II.

What's your background in making games?

I started making games in 2016 when I transferred into the NYU Game Center. I had no coding or dev experience before that. There, I learned a little bit of everything: programming, level design, 3D art, and how to play-test and iterate. I liked the jack-of-all-trades approach because it allowed me to build full experiences on my own. I’ve mostly stuck with Unity since I’m most comfortable in it.

I got exposed to a lot of interesting and cool games through people I met in school. Since graduating, I continue to make stuff on my own and collaborate with a few friends under the name Big Bag collective.

How did you come up with the concept for Titanic II: Orchestra for Dying At Sea?

I can’t really say that I came up with the concept for Titanic II as much as it kind of unfurled itself over time.

Originally, I actually just wanted to test out using the fog and background color to create the look of sinking into deep water. I realized you couldn’t tell there was any downward movement, so I grabbed a few 3D models to throw in the space for the player to sink past.

Around the same time I created the My Heart Will Go On edit on a whim. It was funny, but it also struck a real chord with me. I tried putting that audio over my sinking scene. From bringing those two elements together, things started clicking and I was driven to add more to the experience.

While I was working on the scene where the player watched the Titanic slowly sink down, I showed it to a composer friend Ben Andre who gave me an original song. When I added it to the scene it lined up eerily well, and from then on I purposefully choreographed that sequence to move with the music.

Making a "music video"-like interactive experience is challenging because you can�’t control the player’s timing, so instead you have to design your scene in ways that [make] the player feel like they’re driving the pace while you’re actually directing them.

The rest of the scenes that followed also came one piece at a time. I tried to not rush myself to finish the game and only work on it when I had a clear vision. About two years later I arrived at an ending.

I wanted to create an experience where music was central. It’s responsible for 90 percent of the emotional impact, and I listened to music while getting inspiration for where the game would go next. That’s also why I eventually decided to call it an orchestra.

What development tools were used to build your game?

It was all done in Unity 2019 and written in C#. There were some 3D models that I did end up making myself, and for those I used Maya. For editing the audio tracks, most importantly My Heart Will Go On, I used Audacity.

I think it’s fair to call Models-Resource a development tool in this project. That’s the website that I sourced most of the models from. It’s a treasure trove. Using Models-Resource allowed me to work quickly and focus my attention on lighting, pacing, tone, level design, and the other things I was interested in.

What appealed to you about exploring the watery aftermath of Titanic? What made you want to take players on this journey?

The interest in the aftermath of the Titanic started to appeal to me once I set the edited Celine Dion track to the sinking sequence.

I should probably note that I’d never actually seen the movie when I started, but I knew how it ended just because of how saturated it is into pop culture. I eventually did watch the last forty or so minutes of the movie when I was about two-thirds of the way done making the game just to make sure I didn’t mess up anything.

In the movie, Jack is an angel who doesn’t hesitate to give his life in exchange for Rose. But he’s a human, he must have some sense of self preservation and fear of dying. Was he struck by terror once his body began to fail? Did he feel betrayed that Rose allowed him to do this and for herself to be the one that survived?

While I hope that the arc of Titanic II can be open to interpretation and something that could apply to any situations involving tragedy, loss, transformation, etc. I also decided to lean into the narrative of a tragic end to romance.

I was also really into the themes of huge catastrophes and everything suddenly falling apart—of larger-than-life terror and how people try to cope with it. I liked how the Titanic offered tragedy on both the personal scale and the grand scale simultaneously.

What ideas go into creating a walk in the afterlife? Into making a meaningful wander through the moments after you've died?

I love media that explores the world of the mind, dreams, and manifesting emotional realities as physical ones. Games are a great medium to do this in.

Jack kind of becomes a vengeful ghost—an embodiment of everything he felt as he died, which builds up under pressure as he descends, and then as he ascends, lightens, until his rage eventually melts and evaporates in the sun.

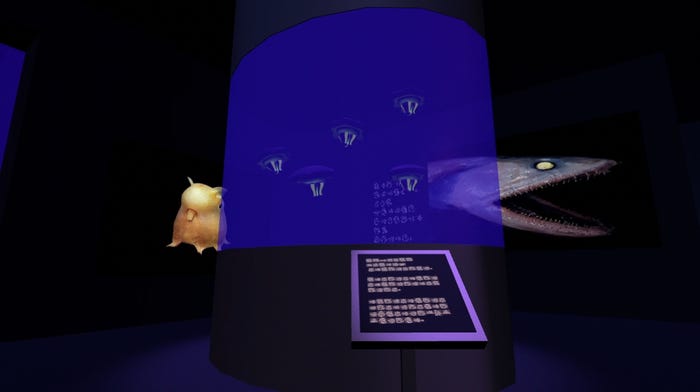

The illegible text is also a part of this. I was inspired by the manga and animation of Cat Soup in which one of the two main characters dies, and as a god of death is pulling them away, it speaks in a similar illegible language which starts to melt the character’s memories.

There are lots of different types of death. I think all of us experience inner deaths and rebirths. To continue living after losing something, a part of you also has to die. In Titanic II I wanted the player to maybe not embody a whole person, but the part that dies as someone mourns.

Or maybe they’re also a person who is dying in the ocean after the Titanic sunk. Or maybe something else. I don’t want to be prescriptive about it. I think of it more as a shape of something.

What thoughts and research went into creating the underwater world players would explore through the sunken ship?

It would be generous to say that I did actual research for this game, but I was surrounded by ocean-themed sources of knowledge. During the first year of COVID, I spent a lot of time watching Twitch streams by the Monterey Bay Aquarium. I just kept being saturated with interesting facts about the ocean and ocean life.

Some of the creatures that I was learning about found their way into the game, like the barrel-eye fish whose transparent head houses the ballroom sequences. I also learned about nitrogen narcosis, a phenomenon where divers can begin to hallucinate and experience powerful emotional changes as they descend into deep water.

I’d always had a fascination with the deep. I’m genuinely terrified of it, even though I love the alien-looking animals that live there. It took me a while to be able to go into the ocean without feeling anxious, and even then, I still feel a sense of dread when I think about what’s below me in the water.

In horror media we usually circle around the same set of fears and types of suspense: ghosts, murderers, being chased, rounding corners, etc. Even in Jaws, which is maybe the closest to capturing this specific ocean fear, it boils down to "big shark," and they never go to the deep waters. I love horror, and I wanted to try and push the bounds of it. I wanted to take something that I was really afraid of, and see if I could make other people feel afraid in the same way.

The game seems to dance between grieving, humorous, and wondrous in its exploration of this underwater afterlife. What drew you to explore so many feelings with your game?

I guess I would say that these feelings are not so different from one another. Grief, humor, fear and wonder are all extremes. They’re larger-than-life emotions that are hard for us to fit into our reality, so all of them come with a sense of absurdity. We’re also pretty powerless in most of these emotions; even the good ones. Horror usually focuses on powerlessness via fear, but I think because of that similarity, horror can weave nicely into wonder, humor, and other big feelings too.

Titanic II also touches on all of these different states because it follows an arc. Since I didn’t really try to plan the arc in advance, I just infused scenes with the emotions that I had at the time. Those feelings naturally evolved as I moved through my own experience.

What challenges did you face in weaving a story and place out of so many tones and emotions?

I was always really worried that I wasn’t going to get the tone right. When I first sent the prototype to friends, I wrote

"The Titanic is weird because it was a tragic thing but it’s been a long time and it’s kinda a joke now. This might feel a bit meme-y. I'm trying to get somewhere inside that space of horrible and funny like the Titanic. That being said, I don't want to make a meme game."

The first person to respond said something along the lines of, "I don’t see how you meant this to be anything other than a joke."

So yeah, I was really worried I couldn’t communicate the tone that I wanted to [laughs] but I just kept at it and, to my surprise, it ended up landing with people in the end.

Humor about disastrous things could seem insensitive, or like it’s just for shock value. But I think anyone who’s lived through something that shook them deeply understands how prying at the connection between humor and disaster not only comes naturally, but is sometimes the only way of looking at the world that makes sense.

How did you decide what moments and discoveries to put in the game? What effect did you want them to have on the player?

For the beginning sinking sequence, I wanted to crank up the fear of seeing weird and big things underwater more and more as you get deeper. It starts off with little fish, then scarier ones, then the giant squid, etc. I just picked things that I knew I would be terrified to see.

The seafloor exploration part is similar. I wanted to capture that sinking terror of suddenly coming upon a giant thing that you couldn’t see the shape of just a moment ago. Water has that really scary capability of hiding things from you until you’re right up next to them.

With the ancient text, I also wanted to hammer in this feeling of being cursed.

Throughout the experience, I wanted to pace things out so that the player has little breaks between moments of intensity. Things build up to crescendos and then go quiet again, then build back up.

I wanted to push against expectations with the pacing. Often, the player is made to wait and watch as large objects sink, float, and swim by. It’s a really tough balance to strike though—to push players beyond a typical, fast-paced experience without breaking their engagement too much. I’m really inspired by film directors who do experimental things with pacing.

The things you discover inside the ship are less scary but try to communicate feelings and narrative. Approaching and entering the ship is like giving into a nostalgic memory of something that’s gone and getting lost in it. Kind of a ghost ship.

The ballroom is the height of nostalgia, but that’s also the moment where it all comes crashing down again and the memory shifts as you get close to the silhouette.

Then it’s quiet again, and from there is the turnaround where the player stops descending and starts ascending again. Everything goes from black to blue, the opposite of the beginning. After beating the player down with two really intense and loud sequences, I wanted to randomly and unexpectedly give them a quiet, redemptive turn, as if a power larger than [themselves] intervened.

Instead of building to another point of intensity, the player is spit out into the aquarium. This sequence notably does not have music. The room chatter sounds and the educational environment have this sterile quality. There’s a distance between the player and the water, suddenly. They’re observing everything scientifically, through glass. We’re able to look at the ocean and the creatures without being swept into it.

Finally there’s the final scene outside the aquarium. This part took the longest out of any of the scenes for me to feel solid about, but I did always know I wanted the player to melt and evaporate.

For some reason, the bright sunlight always felt like a really important piece of this. Probably as a contrast to the lack of light in the rest of the game.

The player has been so shaped and compressed by the deep, but the pain and rage that felt so huge and powerful down in the sea now looks awkward and desperate on land, like a blobfish. You part ways again without saying a word to Rose about what you went through.

Titanic II: Orchestra for Dying At Sea dances between reality and fiction by taking a real place that's drawn from a movie. What do you think this strange mixture does to the player as they explore the ship and their afterlife?

I think it’s kind of like listening to a pop song and putting your own experience on top of it. We process our emotions through stories about other people or fictional people a lot of the time.

Our own experiences are always intermixed with the stories that surround us. In dreams, sometimes we’re hanging out with our real life friends and fictional characters at the same time. They’re like a symbol system that we can borrow from.

I’ve had some people tell me how they see the game as a comment on media, nostalgia, and capitalism because of the characters that I used. Honestly, I wasn’t trying to reference any of the things that the models are from. I just wanted to use the models as if they were actors and props in a new context, but I also can’t ignore the fact that they will inevitably be tied to the media they’re originally from.

What feelings do you hope to evoke in the player with Titanic II: Orchestra for Dying At Sea?

I think I wasn’t so intentional about evoking feelings in the player as much as I just ended up putting my own feelings into it, and then later realized that there was an arc.

The beginning has that rage, sorrow, fear, and humor because that’s what I could bring at the time. I think it would have been impossible for me to plan out the entire arc of the game at the beginning because a lot of those feelings in the later parts were ones that I didn’t have access to yet.

The game took me about two years to make and it grew with me as I moved through my own experience. This is a huge part of why the game had to be made gradually.

I think I touched on a lot of the emotional arc of the game earlier when I talked about what moments and discoveries I wanted to take the player through, so I won’t go through all of those here again. Ultimately, I wanted to create a shrine to the pain, grief, everything that I was experiencing at the time. It felt important to remember it. I didn’t know that it would also end up housing a lot more feelings as it grew.

Getting the emotions right was really important to me, and music was always a huge part of that. For the ending scene outside the aquarium, I agonized over the tone for a while because it wasn’t having the impact that I wanted. I’d been trying to make the end of an arc that went down, then up again, and I’d even asked for another original piece for the ending.

But I eventually realized that the end needed sadness, exhaustion, and weight. I didn’t realize how heavy it could be to let something go. So in the end, I didn’t use the original track and went with Sleepwalk, because it captured that sadness and that tiredness so well.

I think I was successful in enshrining the emotions that I didn’t want to forget. I hope that people who play can get something out of it. Especially if they’re feeling anything like the way I was when I started making it.

Read more about:

[EDITORIAL] Road to IGF 2023You May Also Like