Time Bandit is an idle game that examines how employers steal your time

Time Bandit is an idle game about factory work that asks the player to examine how employers are stealing their time. And maybe they can steal a little time right back.

This interview is part of our Road to the IGF series. The IGF (Independent Games Festival) aims to encourage innovation in game development and to recognize independent game developers advancing the medium. Every year, Game Developer sits down with the finalists for the IGF ahead of GDC to explore the themes, design decisions, and tools behind each entry.

Time Bandit is an idle game about factory work that asks the player to examine how employers are stealing their time. And maybe they can steal a little time right back.

Joel Jordon, creator of the Nuovo Award-nominated game, spoke with Game Developer about creating a game that explores how social and historical forces affect our perception of time, the challenges that come from creating a game that changes in so many ways in real time, and the design decisions that would help reinforce the game's message that player should be mindful about who is stealing their time.

Who are you, and what was your role in developing Time Bandit?

I’m Joel Jordon, and I’m the creator of Time Bandit. I developed it "on my own," but while I didn’t contract out anything, to say this would still fail to give credit to all of the people who built the tools that I used and the countless friends who playtested the game.

I just think it’s important to emphasize that no one ever actually works on their own. This becomes a much bigger problem when it comes to mythologizing the bosses of game studios—even the smaller indie ones��—as great artists while failing to give credit to all the workers and contractors that they relied on. I just want to point this out because Time Bandit is really concerned with how things are actually produced and I strive to be as transparent as possible about my own process and even to unveil it through the game itself.

Everything about videogame production and capitalist production in general demands that someone take overall ownership of the product in order to maintain the claim over a piece of property that can be profited from (also to build a valuable brand, nowadays) and artistic production deserves better than that.

What's your background in making games?

I have been working on Time Bandit for so long that it now makes up, by far, the largest part of my background in making games. I know that this means I’m doing the thing that everyone knows you’re not supposed to do—work on a huge project for a really long time. But a large part of what I’ve enjoyed about making Time Bandit has been learning so many skills, and to some extent, I don’t see the difference between doing that with one large eclectic project and a bunch of small ones. I think I probably would have learned even more doing the latter, but still, a lot of that advice seems to be concerned with efficiency and it’s not worth overthinking what you "should" be doing if you’re doing what you want anyway.

I also just enjoy really living with a project—getting lost in it and coming out different on the other end. With all that said, I’m definitely going to rein things in a bit next time around. I just didn’t quite know what I was getting into when I started this.

I have worked on some smaller, hybrid digital/physical works for festivals, always with a focus on the experimental and political. My most successful project (and I define success by the effect that it had on people) is Boss Battle, a work of interactive theatre that I originally made for the Come Out & Play Festival in New York City. It’s a game about negotiating with your boss and unionizing with your coworkers. I designed the rules contained in the game’s work contract to be ambiguous and negotiable, and I was so happy with the game because players discovered all kinds of ways to break them that went beyond what I even expected. The rules don’t say anything about going on strike, for example, but most games ended with the workers going on strike. I was also really happy with the spontaneous discussions it prompted the players to have afterwards about the problems of a capitalist economic system.

How did you come up with the concept for Time Bandit?

The time mechanics in Time Bandit were originally inspired by Michael Brough’s VESPER.5 and, believe it or not, Animal Crossing. I was surprised to have this really meaningful experience with VESPER.5 where the moment each day when I played it became important to me. Then, I was searching for a replacement for that feeling once I finished the game, and I started playing Animal Crossing. I quickly found all of the more work-y parts of the game tedious and didn’t want to engage with them, and so I started to check in on my town every day for no more than 10-15 minutes just to talk to my villagers, listen to the music, and do small things like water my flowers and walk along the beach.

That made me start to think about how the real radical potential contained in Animal Crossing lies in the way that it entices you with all the traditional kinds of game loops but at the same time offers significant alternative aesthetic points of interest. To me, the fact that all that stuff is there makes the choice of not engaging with it much more powerful than in a game that only treats you to a more relaxing experience. This is because, at some point, the game poses the question to you with alarming force: how do you want to spend your time?

I also happened to be replaying the old Metal Gear Solid (MGS) games at the time—an influence on Time Bandit that’s more obvious. MGS (the original trilogy mainly) has always been formative for me in a whole variety of ways, but perhaps the most important for Time Bandit is the way that it plays with and breaks down Triple A realist videogame forms to express its politics. I honestly think MGS is more formally successful at conveying its politics than it usually gets credit for. It’s almost a cliché that people like those games "in spite of" the pacing and overly-long cutscenes, but I think it’s precisely through the much-maligned disjunction between its gameplay and story that it creates an unusual space for players to reflect.

And just to mention one small specific thing that I took a lot of inspiration from for Time Bandit, I love the way the codec blends a hint system and details about the in-game world with encyclopedic details about the real world. The line between reality and the game is always blurry, and that extends to the wider treatment of Cold War history in the game. And, at least in my personal experience, I have to give MGS credit for originally teaching me about American imperialism and probably for eventually inspiring a lot of my other political convictions.

How many other videogames, especially big-budget ones, can take credit for doing something like that? Maybe Pikmin’s not quite as explicit about its politics as MGS, but this great, dark comedy anti-colonialist satire is another Nintendo game that you might be surprised to hear was an influence on Time Bandit. Among other things, I actually got the overall game loop of resource management and setting various things in motion in order to open up access to the things you need to collect from Pikmin. The difference is that you’re playing as a powerless worker in Time Bandit rather than as the boss controlling workers.

What development tools were used to build your game?

I used Unity, Aseprite for some pixel art, sound effects from freesound.org, etc. In the spirit of what I was saying before about how no one is ever working "on their own," really all the innumerable people who have ever worked on these tools and made them accessible to people like me deserve credit. We live in a time of unprecedented accessibility of tools, which is the result of the work of so many people.

Real time is an important element of the game. What interested you in exploring the use of real time and connecting it with labor?

It started from the idea of making a more goal-driven and story-driven adventure game using the real-time mechanics of Animal Crossing. At the time, I was also quite obsessed with thinking about my own experience of time and trying to make good habits for myself while breaking bad ones. However, while I was doing my best and making some progress, I couldn’t help thinking about the limitations of making these changes in my life.

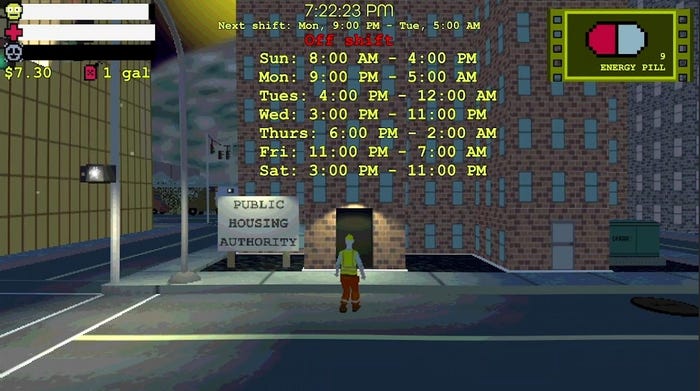

So, Time Bandit isn’t really about making individual changes, like practicing meditation or mindfulness, in order to alter your experience of time. The anti-capitalist story about a company trying to take control of time in order to make you work for them forever instead makes it clear that this is about how historical and social forces shape our experience of time. Individual changes aren’t enough if you have to give so much of your time to doing work you don’t care about to make someone else rich. As it goes on, the game tells a story of taking collective action to change our society’s whole mode of production in order to have the time to do the work that we value at our own pace and to take care of ourselves and others.

What thoughts went into designing the tasks players would have to do for work? Then, how did you decide how much real time they would take?

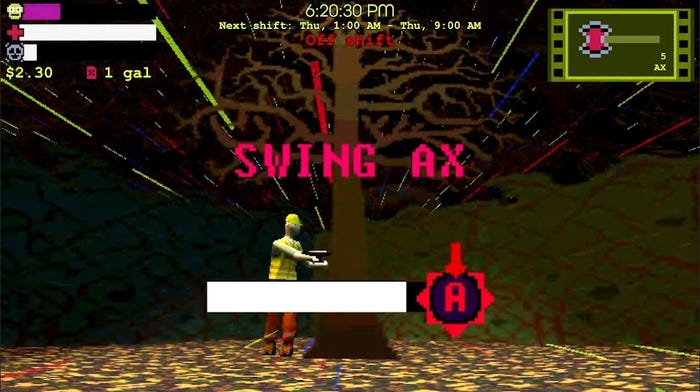

I originally thought about the tasks from a game design perspective of what would work best to create level design that worked with the puzzles and stealth and real-time mechanics, so they are pretty abstract and not very realistic. For some reason, there are all these boxes in the way and they are all arranged in a grid. There are also heaps of trash that you have to compact in order to turn them into movable boxes. I was thinking about the prevalence of industrial waste when I first came up with the idea to put so much trash in the game. It also happens to work well with the real-time gameplay: trash takes longer to get out of the way due to the compacting, so you may want to avoid moving it as much as possible. And I just think it’s pretty funny to make players play with garbage.

The fact that this is largely a Sokoban game also mainly came about as a game design decision, and it only occurred to me retrospectively that the fact that you are doing something so mundane as moving boxes around is appropriate to the story.

The time that these things take also isn’t realistic, of course. For some reason forklifts take a half hour to finish moving. In the first part of the game, these timers are just designed to ensure that players can make one or two moves before setting the game aside and coming back later. I don’t want to spoil too much, but as the game goes on, the lengths of the timers are going to fluctuate significantly.

I’m doing this in order to play with game loops. Time Bandit actually has, believe it or not, a quite traditional and, judging by the reactions of some of my playtesters, compelling game loop. The game basically involves slowly solving puzzles over time, sneaking out the time crystals once you’ve gained access to them, and then selling them for money in order to buy fuel to solve more puzzles and collect more crystals.

And I would push back against the suggestion that just because you’ve extended a game loop in time you’re doing a better job of respecting the player’s time—it seems to me that you might just be increasing the player’s anticipation by making them wait (look at free-to-play games or Animal Crossing). So, I want to intensify this game loop at times. Not too much, since you can get this experience from just about any other game, but to try to place it in the context of labor before I begin to break down the loop with some dramatically different experiences of time. I want to get the player to ask themselves how they want to experience time and what changes in the world that would take.

What ideas went into the creation of the workplace?

The level design, like the work tasks, is pretty abstract. It looks more like a puzzle box than a real workplace. But I focused on putting a lot of industrial waste everywhere. I was brainstorming while walking around the city when I decided to make that a large part of the aesthetic. It would be nice to be able to make a more colorful game next time, but I feel like I would need to live in a more colorful world to do that.

What challenges did you face in creating a game that is always changing in real time? That is affected by the time of day?

Testing was a huge problem. I had to move my system clock forward all the time. And when you tie things to real time, there are also just so many possibilities of overlapping events and I can’t account for them all, so it produces a lot of bugs. The save system is complicated, since every time you load the game it has to check the original state that it was left in and then update it based on the amount of time that has passed. I tended to have to program everything in the game in two ways: one for updating it progressively while you are playing it and can see it changing and the other to update the state of everything when you return.

I also spent a lot of time on small details that you will only see if you’re playing at a specific time under specific circumstances. A large amount of it is unlikely to be seen by most players, but when it’s real time, you kind of have to work on all these details, and I hope that they’ll help make the game feel like something you are really living with.

How did you work to combine a daily job and stealth? Weave your average workplace into someplace to sneak through using the people and objects that were already on-site on a job?

The real-time puzzles and the stealth are actually going to become more interwoven than is apparent from the first part of the game, and I’m really excited about that. Again, I designed this in a more abstract way rather than to create an especially real-feeling place, but basically the levels are designed to be moved through repeatedly because you’re constantly going back into the same spaces to steal different time crystals and then sneaking them back out.

It’s inspired by the way you return to the same level to open up pathways and collect different things in Pikmin, which derives from how you return to the same level to get different stars in Super Mario 64. I feel that players might complain about how returning to the same level so many times gets repetitive, but I think this kind of reaction is probably due to the game making it overly transparent how you are spending your time, since these are video games we’re talking about and players are otherwise accepting of nearly unending amounts of repetition.

In any case, it’s a big part of the game’s overall structure and design, so no compromises. Your choices early on in opening up shortcuts through the space (or creating obstacles for yourself) will have a big impact, because you’ll be retracing your steps through these spaces often. Later on, the guard rotations will change and become more difficult, and it will be significantly safer to sneak time crystals out from deeper in the world if you’ve spent the time to open up alternative paths and not made things harder for yourself. It’s a game about thinking ahead and making commitments with consequences that can be permanent.

What work went into creating a narrative that would unfold over days and weeks? How did you put your story together?

The value that I found in this type of narrative was that I had an unusual amount of control over the pacing of the story. Basically, the way it works is radio conversations are used for a lot of the main plot points, and they act like real-life phone calls in the sense that characters will pay you these calls on the basis of the number of real-time days you’ve checked in on the game. So, this allows me to introduce something and know that it will be, for example, at least another 2 real-time days before the player will receive the next phone call.

This is important to me because I wanted to create space for the player to reflect on the story’s ideas, and I can even have some sense of how much time they’re being given for each idea. I think this shows some of the expressive power you can get out of noninteractivity, not just in taking control away from the player but even when they’re not playing the game at all. I’ve taken a lot of other narrative techniques from Brechtian theatre, but real time is a pretty unique tool that I had for getting players to integrate the game into their life and remind them of the real world all the time.

It also struck me that players are already pretty accepting of being spoken to directly by video games. To bring up MGS just one more time, I love the way that characters will, without missing a beat, just nonchalantly drop what buttons you have to press to perform an action in the middle of an otherwise totally normal conversation. And I find games like The Beginner’s Guide, Getting Over It with Bennett Foddy, and Jack King-Spooner’s Blues for Mittavinda really inspiring for going further and holding a direct dialogue with the player to a dramatic and sometimes radical effect.

Aside from doing what I could to directly remind the player of the real world, I also developed all of the characters as representatives of their precarious economic situation and how they respond to it. There’s a lonely, debt-ridden office worker, an overzealous revolutionary, a complacent middle manager who sucks up to power, etc. Some of the characters will have more reactionary or more radical responses to their situations, but the important thing is that they’re all directly shaped by a context much like our own.

What drew you to have a choice where players could turn in the fruits of their labor to their bosses or try to "steal" them to sell for themselves? To connect that with your bosses stealing your time?

I can’t really answer this question without getting polemical, so I apologize but it can’t be helped. The whole capitalist economy depends on the exploitation of labor. And by "exploitation" I mean something very precise: companies pay less for labor than they make from selling the products of the labor. The company is taking a portion of the value that was created only by workers. So, all capitalist companies are stealing from their workers.

The typical counterargument to this is that companies provide the means of production, without which workers couldn’t make the products, which is true. But our economic system doesn’t need to be organized like this. The only reason that some people and not others own the means of production is because they have the capital to invest in it. And this whole thing is predicated on the ownership of property, which was originally obtained by violence and is sustained by labor exploitation.

I think most workers basically know how this works from experience, but I hope that allowing players to turn the tables and steal back in Time Bandit gives them the opportunity to feel subversive and reflect more on—and hopefully act in the real world to help bring about—a society that would be organized differently along the lines of shared resources and not the theft of that which is most valuable to everyone in their limited lifetimes: their time.

There is a special appeal to a game where things happen in real time—a sense of concreteness to the place, or a feeling that these unique moments you've seen are truly special. What did you feel in creating such an experience in working in real time?

Let me give one example (my favorite). Programming this game’s sunsets was some of the most fun I have had programming. It felt like painting in code because I had an uncommonly direct relation to the results, which was also helped along by the fact that it was a fairly painless process that couldn’t produce too many bugs. So it was special to me, and it’s also something I hope is special to players. If you play the game during sunset, I hope you notice it and stop to watch. Or, better yet, that it reminds you to go outside and watch the sunset—which you can do, because the game’s day-and-night cycle and weather are tied to your real-life location.

I think things like this really help to remind players to think about the time they’re spending with the game and maybe to relax and take a break from making progress.

What do you hope the player takes away from Time Bandit?

I’ve probably already run the risk throughout my answers to the other questions of making this game sound like it’s way too didactic. I think it’s clear that it is really important to me that the game does deal with big, serious things. The first part focuses on things like labor exploitation and technological automation, while later parts deal with the violence of colonialism and environmental and economic crisis. But I’ll end by saying that the game explores all of this through over-the-top, absurd and darkly-comic conspiracies and character drama, and I do hope it’s pretty fun to play.

Read more about:

[EDITORIAL] Road to IGF 2023About the Author(s)

You May Also Like

.jpeg?width=700&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)