Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

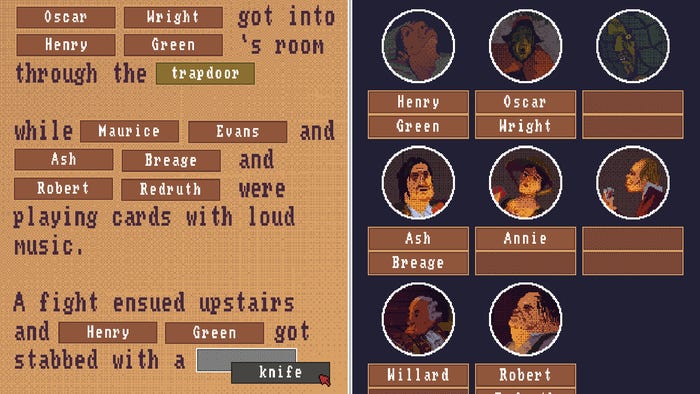

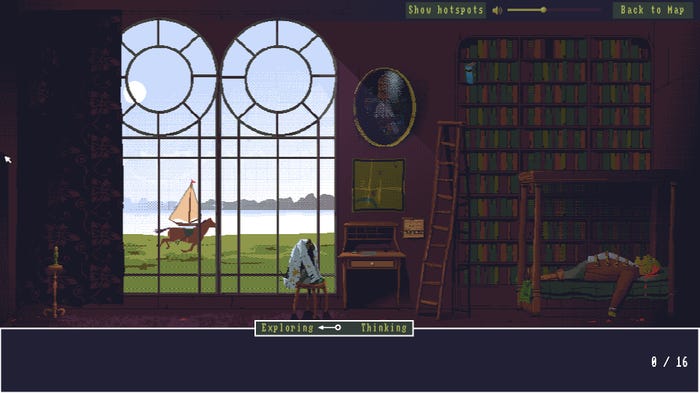

The Case of the Golden Idol trusts the player to solve a complex forty-year old mystery, asking them to piece together the culprits, tools, and locations involved.

This interview is part of our Road to the IGF series. The IGF (Independent Games Festival) aims to encourage innovation in game development and to recognize independent game developers advancing the medium. Every year, Game Developer sits down with the finalists for the IGF ahead of GDC to explore the themes, design decisions, and tools behind each entry.

The Case of the Golden Idol trusts the player to solve a complex forty-year old mystery, asking them to piece together the culprits, tools, and locations involved.

Game Developer caught up with game designer Andrejs Klavins, one of the creators behind the Excellence in Design and Seumas McNally Grand Prize-nominated work, to discuss the importance of tying puzzles to the narrative to make them feel satisfying and logical, how they brought in testers early and often to ensure the puzzles came together in ways that made the game feel satisfying, and the processes they used to analyze their puzzles to keep them from being too easy or hard.

Who are you, and what was your role in developing The Case of the Golden Idol?

I am Andrejs Klavins, game designer and manager of Color Gray Games. I developed the code and worked together with my brother, Ernests Klavins, on the game design, story, and puzzles.

What's your background in making games?

I have worked for more than 10 years in game design and IT product management. Even though I’m not a developer, I have developed some hobby game projects in the past.

How did you come up with the concept for The Case of the Golden Idol?

We felt that there were still unanswered problems in the point-and-click detective genre that had yet to be solved in a satisfying way. We wondered why there were so few successors to the Return of Obra Dinn, a boundary-pushing title that laid the foundations of a great framework on how to feel like a detective.

We identified three main issues; gameplay flow, disjointed narrative, and the communication of insights when the player is solving mysteries. After this, we prototyped a few versions of our own on how to deliver that experience until one of them stuck. This would become The Case of the Golden Idol.

What development tools were used to build your game?

For prototyping we used Construct and for development we used the Godot engine. Ernest worked on art using Aseprite.

In a past interview with us, you mentioned that it is difficult to test your own mystery game (since you know the answers). How did you find good testers to try the game out with? What data did you collect from them to get a feel for how your puzzles were working?

We just asked our friends! Luckily, we have quite a lot of gamer friends and many of them find deduction games interesting. We would have a regular [group of] four or five people with whom we would test each scenario. After Playstack became our publishing partner, the product and marketing team members gladly joined the testing efforts, making our lives much easier.

We did not rely on any hard quantitative data; for us, playtest interviews were much more important. During these, we would carefully monitor what players did and said in the game. From that, we made assumptions (sometimes that we could validate with the tester) of their thoughts and feelings during the playtest which would inform whether the scenario was working as we wanted it to.

When you receive data from testers, how do you decide if it's valuable or not? How did you decide on how to alter the game based on this data?

Data helped us build a vision of what a good experience of a scenario would be like. For example, if a player understands the main mystery immediately and then is stuck for thirty minutes on some technicality, that�’s bad. There were things that we didn't want to be too difficult and things that we didn’t want to be too easy. Balancing this, and in turn ensuring good pacing throughout the scenarios, is very important for us. If there were other, non-linear ways to discover insights, it was great, but not obligatory.

After we got the main pacing right (which is super easy to break at any moment) we went back to iron out smaller bugs (for example, people would have difficulty recognizing a visual of an apple, which would need redrawing).

Finally, after all the iterations, we’d have some final playtests, and if they were smooth, we’d consider the scenario done.

How early were you bringing in testers in development to check on your mysteries and puzzles? And why did you bring them in when you did?

As early as possible. This was to avoid putting effort into something that didn’t work. We’d test early puzzle prototypes with basic visuals or excel tables on each other. Then, we’d make (with placeholder art) an early prototype of a scenario and have some forgiving relative (usually my wife) play it to see what parts needed simplification and what needed obfuscation.

Was there anything you did to the game to make it easier for testers to check on certain things? To focus them on what you wanted to know about?

Not really, because testing the difficulty of the scenarios for players is one of the key purposes of testing. However, we did realize that the scenario felt harder for our testers as they were playing the game only in one specific scenario each time, therefore they would forget or simply not know about the context of previous scenarios.

In a previous interview with Game Developer, you mentioned developing a 'Thought Path' to see if players had enough clues (or too many) to solve a mystery. Can you walk us through one of the puzzles and how this thought path worked to help you improve it?

SPOILERS AHEAD

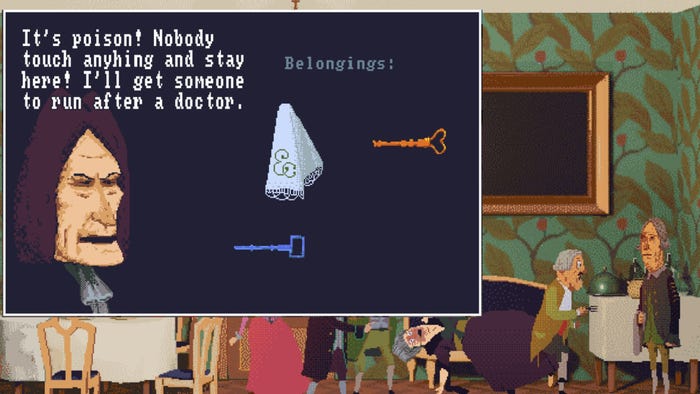

The 5th Scenario "Intoxicating Dinner Party" is a riff on the classical salon mystery—a lady Rose Cubert has been poisoned at a posh dinner party. So, there are a number of things players have to understand to solve it:

Where did Rose sit at the dinner table?

Which unique substance she had consumed? The stomach tonic.

Where is this substance stored? In a safe.

Who has access to this safe? The butler and the owner of the house. A copy of the key hangs from one of the servant rooms.

Which servant resided in that room? The recently hired maid: Ada Baker.

In the suspicious room are instructions "Take fourth from every line." If applied to a text in Ada’s pocket, you can decode secret instructions to poison the owner of the house.

Some of these can only be figured out sequentially, but some in parallel. During the testing, if players would suddenly bypass many of these steps with some other clue, we knew that we had to remove that clue because it was making parts of the game superfluous.

Doing actual deduction in games is incredibly compelling. What do you feel makes it so exciting for the player to feel like they figured things out without help (or without much help)?

I already knew that people love problem-solving. Games in general are problem-solving with the purpose of entertainment. However, to be more precise, we knew that people loved Escape Room games in which you solve small portions of puzzles to progress in the room. It’s fueled by intrigue, a sense of progress, and being smart by solving a series of brain teasers.

I felt that what these games were lacking was a coherent narrative to discover. These experiences are often very arbitrary—you solve a Sudoku and a secret stash opens behind the shelf. Why? Nobody lives like that. The moment you introduce that narrative, I think it elevates the puzzle-solving, grounding it in reality and making it more purposeful.

At the same time, sharing a story as clues for puzzles makes the narrative much more engaging because nobody is attacking you with a wall of exposition text. I think only a very few games can make walls of text work (like Disco Elysium) and most of the time I just try to skip them. The game has not earned enough of my attention to undertake all that reading. You have to lure in players that care about the narrative. This is something Portal did brilliantly, where you just get scraps of some shadowy mystery—the more you play, the more hungry you get for those scraps.

What thoughts go into creating a good, long mystery? What ideas went into making a mystery that spanned forty years and many deaths? Into tying it all together in a satisfying way?

We started with a sort of archetype of a narrative which delivered a certain message. Creating that archetype requires certain narrative beats as well as a protagonist and antagonists. We started by understanding which of the narrative beats a single scenario fulfils, and then we would work on it as an individual story with its own mystery.

You don’t need to figure out all the details, but you should know where your story is going and how you want it to end. If you fail to do this, you’ll suffer the fate of many TV shows where an intriguing premise gets messed up by an unsatisfying ending.

The way Golden Idol ends was absolutely intentional and planned from the very beginning.

What challenges did you face in keeping this complex story straight yourselves? How do you keep up with your own story when it's very complicated?

I feel like we didn’t have any moments where we confused ourselves by the complexities of the narrative. This might be because the main storyline is relatively simple and can be kept in mind easily. It could also be because, before working on each scenario, we would have at least a week of just brainstorming and having detailed discussions about this scenario and how it would fit into the bigger narrative arc. This eventually lead us to memorize all the key events and every character, as well as their motivations.

Of course, we methodically document timelines and characters to avoid messing up smaller details.

For us, a bigger challenge was to align on things that we believed because we are both quite demanding of what we wanted to deliver. At any moment, either of us could challenge that something didn’t make sense from a character’s motivation point of view, real-life logic point of view, or the needs of the narrative beat. Therefore, we’d spend numerous hours quarrelling about it, which I think is a great method for creative work.

Read more about:

[EDITORIAL] Road to IGF 2023You May Also Like