Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Gamasutra presents an annotated contract between Activision and Spark Unlimited for 2004's console title Call Of Duty: Finest Hour. This is the first time a major game development contract has been disclosed publicly, and it is presented here in its entirety.

January 12, 2007

Author: by Dave Spratley

[EDITOR'S NOTE: The following article reprints the entire development contract for Spark's November 2004-released console game Call Of Duty: Finest Hour, which debuted for PlayStation 2, Xbox, and Gamecube following Infinity Ward's first Call Of Duty for PC. We have asked three leading game attorneys - Tom Buscaglia, Chris Bennett, and Dave Spratley - to comment on the entire document, which even includes milestone payment specifics, and was released to the public as part of a legal battle between Spark and Activision.]

Tom Buscaglia: Los Angeles Superior Court judge Tricia Ann Bigelow recently unsealed the exhibits filed in a pending law suit that included a three-game development agreement between Activision and the then newly formed Spark studio.

Contracts such as these are rarely made public because they inevitably contain confidentiality provisions that prohibit the publication of or even talking about their terms. But once the contract was filed as an exhibit in the lawsuit, and then unsealed by the court, the contract became public information.

This was a just too good an opportunity to miss. So, when the editors of Gamasutra asked me to review and comment on the agreement, I jumped at it. I have done my best to summarize each section of the contract and to include comments where appropriate. I hope you find it both illuminating and educational.

Chris Bennett & Dave Spratley: Here’s a quick summary of the dispute. In August 2005, Spark sued Activision for breach of contract, fraud and misrepresentation. Spark claimed that:

Activision threatened to stop funding the games unless Spark agreed to accept fewer royalties and other less-favorable terms.

Activision charged Spark millions in assistance costs that Spark did not approve.

Activision did not negotiate in good faith regarding sequels.

Activision did not provide meaningful bridge funding.

Activision hired away some of Spark’s employees.

In October 2005, Activision counter-sued for fraud, breach of contract, misappropriation of trade secrets, trade-mark infringement, false designation of origin, and false advertising. Activision claimed that:

Spark misrepresented that it had the necessary talent, knowledge, skill and experience to develop the games.

Activision paid Spark’s legal fees to defend against Electronic Arts’ accusation that Spark stole trade secrets and confidential information from EA.

Spark repeatedly failed to meet its milestones, even when Activision provided substantial support.

Spark’s proposal for a sequel was half-hearted and deficient.

Spark failed to return development kits and computers containing source code to Activision.

Spark breached its confidentiality obligations when it filed the lawsuit.

Tom: This section identifies the parties (A. and B.) and the basic objective of the agreement and that it relates to a three-game deal (C.). There is also a reference to a preexisting Letter of Intent (LOI) entered into on July 22, 2002 (D.). I suspect that much of the interim time was probably expended on negotiating the details of this final agreement.

Products and Exclusivity - This is where the three AAA (1.1) titles to be developed by Spark under the contract are described. The second (1.2) game will either be a sequel (probably based on the success of the first one) or a new game based on either original IP or licensed content. The same for the third game covered under the agreement (1.3).

The three games are collectively referred to as “the Products” (1.4) and the general scope of work it set out (1.5) and the term “Sequel” is defined (1.6). Activision was to have an exclusive relationship with Spark through the completion of the second game in the series. After the delivery of the second title Spark could devote a part of their resources to other projects (1.7). The description of the first title, referred to under the working title of “Tour of Duty” is also set out (1.8).

Platforms and Formats - The target platforms are simple - PS2, Xbox and Gamecube (2.1).

Chris & Dave: The last few words of section 2.1 also require Spark to develop for the PS3, 360 and Wii (even though those consoles weren’t on the market in 2002)!

Tom: Ownership - It looks like Activision owns everything (3.1), the game assets (3.2), the technology (3.3) and even co-owns the tools (3.4), which are usually left for the developer. Considering the scope of the deal this could be reasonable. In effect, Spark is a captive third party studio during the term of the agreement.

Chris & Dave: In section 3.3, Spark grants Activision a “license” to exercise its moral rights. This won’t be effective in many countries (such as Canada) where moral rights are protected. Moral rights arise when a copyrightable work (such as game code, art, music, etc.) is created. Moral rights give the author of the work the right to have his or her name associated with the work and the right to prevent anyone from modifying the work in a harmful way.

Moral rights can’t be transferred; they can only be waived. Also, a company (such as Spark) can’t have moral rights; only the people who worked on the game can have them. So the best way for a publisher to draft a moral rights clause is to require the developer to get moral rights waivers from every person who contributed to the game.

Section 3.4 gives Spark and Activision joint ownership over the games’ development tools. This is unusual (often the developer will solely own the tools). Joint ownership can cause problems in the future if the agreement does not specify what rights each party has in the jointly-owned property. For example, can Spark license the tools to a third party without Activision’s consent?

Tom: Of course, Spark has to make the game (4.1.1) in conformance with the TDD (Technical Design Document) and the GDD (Game Design Document). Delivery of the game in compliance with the milestone schedule for the first game (Exhibit A) and the following two games milestones will be done by subsequent amendment created later.

They also are obliged to provide demos (4.1.2), provide ongoing bug fixes to the games (4.1.3), return any software provided to it by Activision (4.1.4) and create any necessary installers (4.1.5).

Chris & Dave: Demos are critical to the success of a game, but they can also be time-consuming and expensive, so it’s a good idea for the agreement to contain more detail about what kind of demos are required, how many are required, and when they’re required. This will help with budgeting and sticking to the development timetable.

Section 4.1.3 requires Spark to provide free bug fixes “for a reasonable period of time”. This can only lead to future disputes: Spark might think six months is a reasonable period of time, but Activision might think 5 years is more reasonable. It’s better to use a specific time period instead.

Also, Spark is required to fix “Defects” which include “deviations from commonly accepted standards for normal and correct operation of computer programs.” It’s normal to require a developer to fix a deviation from the game specifications, but requiring a developer to comply with “commonly accepted standards” is vague and uncertain. Again, it just sets the stage for a future dispute about what these “commonly accepted standards” are.

Tom: Activision takes an active role in the development by providing “editorial feedback and substantial creative and technical input in all aspects of the Product design and development” (4.2.1). And you thought you have problems with your publisher’s producer! This provision guarantees Activision creative and technical control over the games, from start to finish.

Chris & Dave: Section 4.2.1 requires Activision to give Spark a game engine for the first game. However, the section doesn’t specifically give Spark a license to use the engine. This license is implied, but what are its terms?

Activision will also provide end user telephone support (4.2.2), handle packaging, including design, (4.2.3) and handle distribution and sales (4.2.4).

Section 4.2.2 only requires Activision to provide end user support in portions of the world where Activision makes that support available. In other words, Activision is only obligated to provide support if it decides to do so. This is a great way to draft your obligation clauses if you’re the publisher!

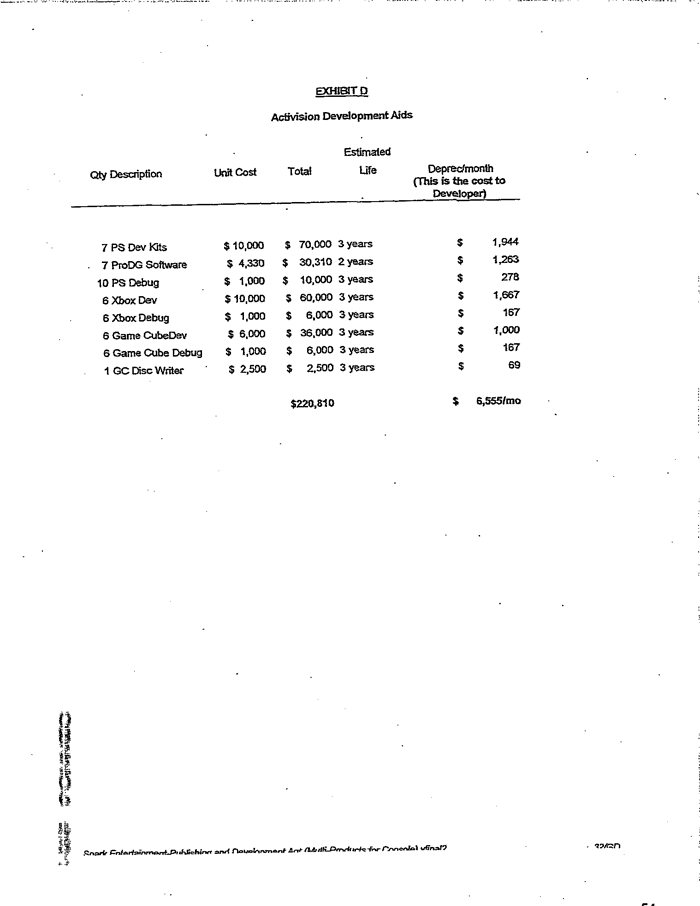

Tom: Here, Activision agrees to provide Spark with certain Development Aids (4.3.1) that are set out in detail in Exhibit D to the Agreement. But they charge the developer for the depreciation on these assets. The “Activision Development Aids” are defined (4.3.2) to include both Activision’s and Third Party development tools and services, including the console dev kit and debuggers (4.3.2). Of course, Spark is prohibited from using any of these “Aids” for anything other than the Games developed under the contract (4.3.3).

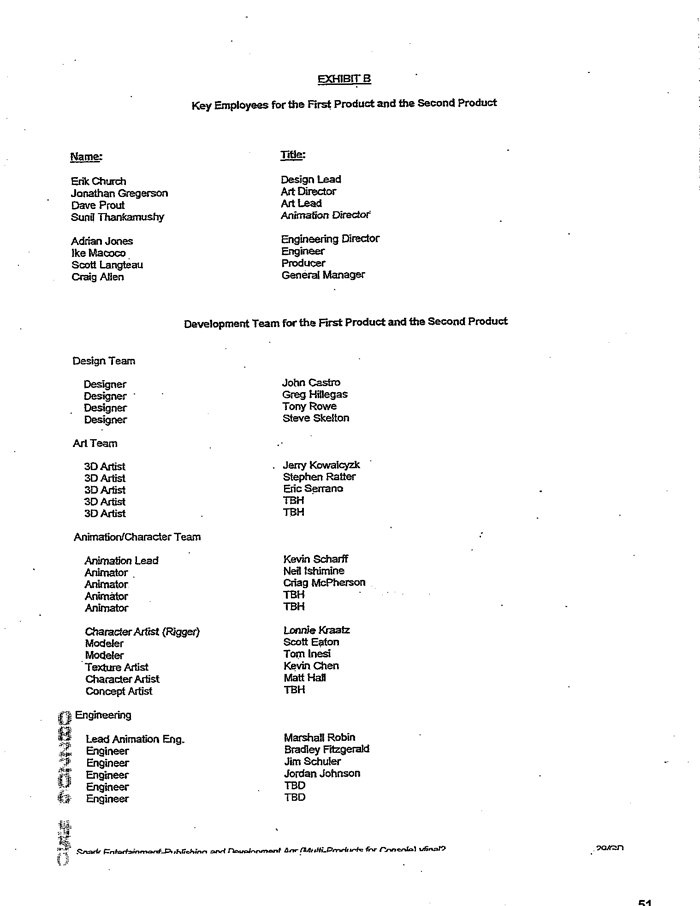

Development Team and Updates - In a situation like this one, where the development team is experienced, but the company is new, it makes sense for Activision to require the developer to retail its leads throughout the term of the contract (5.1). These leads, listed in Exhibit B as Key Employees, were required to work exclusively on the first two games.

Activision also required that these Key Employees sign employment agreements with Spark sufficient to keep them on board for the projects. And Activision has the right to approve the terms of these minimum four year contracts, so you can bet they had non-competes in them.

Chris & Dave: Requiring the Key Employees to sign long-term employment contracts might give Activision some comfort, but there’s nothing stopping an employee from quitting at any time. Non-competition clauses are one way to convince employees to stay, but these clauses are controversial and difficult to enforce in many jurisdictions. More on this in a bit.

Tom: Similar restrictions are placed on the entire “Development Team,” also listed in Exhibit B (5.2). They are also required to work on the initial two games exclusively and not work on any other games after the first two are finished that can interfere with their work on Game three. The Developer also has to provide weekly progress reports to Activision and allow Activision access to the development team throughout the development (5.3, below) and provide periodic builds of the games (5.4).

Chris & Dave: The agreement does not specifically prohibit the parties from soliciting or hiring each other’s employees. If it did, it would have helped Spark’s case against Activision.

Spark might also have a case against the employees who left. Spark could sue them for breaching any non-competition provisions that might have been in their employment agreements, but this would be controversial. Electronic Arts and Ubisoft have publicly debated whether employee non-competition provisions are appropriate and legally enforceable. Last year EA's Montreal GM sent a letter to Ubi's GM condemning Ubi's practice of requiring employees to sign non-competition agreements. This followed a lawsuit between EA and Ubi in 2003 regarding EA's hiring of former Ubi employees.

Tom: Milestone deliverables, as set out in Exhibit A, are due in accordance with the delivery schedule in Exhibit A with a written notice of delivery is required and, if the deliverable is late, a written notice is still required. Seven days late and Activision can terminate the contract for cause.

Chris & Dave: Typically a developer will want an exception for late milestone delivery caused by the publisher. This exception isn’t in the Spark contract, so Spark is required to deliver on time even if Activision caused development delays. Section 6.2 does deal with Activision’s delays, but it only applies to delays which occur after a milestone has been delivered.

Tom: Fortunately, the delivery schedule can be modified by a subsequent written agreement between Activision and Spark (6.1). Activision has ten days to accept or reject the deliverable.

Chris & Dave: Activision can reject a milestone if the milestone doesn’t conform to the specifications, or if it is “unacceptable for some other reason” (section 6.2(c)). In effect, this means that Activision can re-write the specifications throughout the development process. Publishers generally given themselves this ability to ensure they get the game they want. The problem for developers is that changing specifications can cause delays and can add expenses, so a fair “change order” process should be included in the agreement to deal with this.

Tom: The delay in acceptance by Activision beyond 15 days automatically extends all delivery deadlines. Once Spark is notified of the deficiencies in the deliverable Spark has no more than 10 days to correct them (6.2). This procedure iterates until either the deliverable is accepted or, at its option, Activision can cancel the contract with Spark and have another developer complete the milestone or assign the Game to another developer and deduct that developer’s fees from the payments due Spark (6.3).

Activision retains final editorial control over the games, with adjustments to the payments and deliverable schedule (6.4). The drop date for the first game was set as June 1, 2004 (6.5). A comprehensively documented deliverable also had to be delivered on ten working days' notice with the final, and pretty much any time Activision asked for one (6.6).

Activision retained the right to accept or reject any milestone and acceptance had to be in writing. Even if Activision paid a milestone was not deemed accepted unless the acceptance was in writing, with the payment due ten days after the written acceptance. Of course, any payment or late acceptance was not considered a waiver of he requirements of the agreement or of constitute any extension of the preset milestones (6.7).

Tom: Spark was required to produce any additional enhancements to the game to keep it competitive, and agreed to negotiate any changes to the milestones and payment schedule or Activision could hand off the enhancement or the project to another developer (7.1). Activision also retained all rights to port the game to other platforms (7.2).

Sequels - Activision retains the rights to all sequels. But Spark had a right of first negotiation which required them to accept a deal within ten days.

Chris & Dave: The right of negotiation is the most common sequel right granted in a development agreement, but there are other possibilities such as a right of first refusal (the publisher must offer the deal to the developer first) and a right of last refusal (the publisher must give the developer the right to match any existing offer involving another developer).

Tom: If Activision offered any sequels to another developer on more favorable terms than those offered to Spark, then Spark was given another ten-day period to accept the revised deal.

Chris & Dave: This is the matching right, or the right of last refusal.

Tom: Spark was also required to assist any developer making a sequel and would be compensated for any such work (8.1).

Chris & Dave: Spark will only get compensated for this assistance if it “reaches a material level.” Spark will likely think that any work is material, but Activision might not agree. This could lead to future disputes.

Tom: Foreign Language Translations - The games were to be delivered in English and also in eight foreign languages, with Activision supplying the translated voice and text and the developer incorporating them into the games for the localized versions (9.1). Additional localizations would be paid for by Activision at a negotiated price not to exceed $10,000 each (9.2).

Chris & Dave: Developing eight language localizations in double-byte enabled code is expensive. Spark is required to provide these localizations at no extra cost, so presumably Spark factored in this expense when it was negotiating the advances.

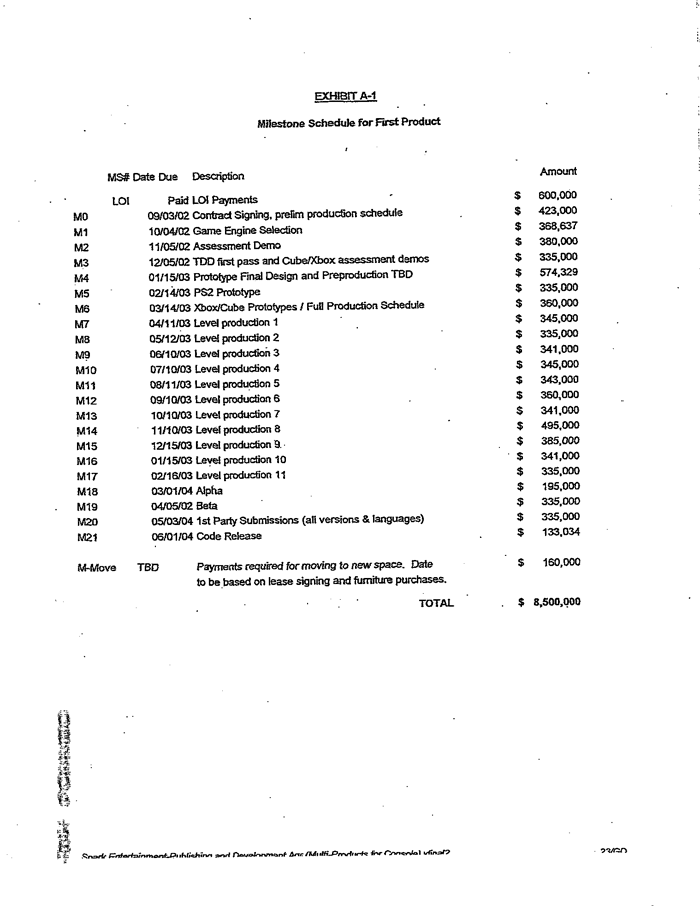

Tom: Advance Payments - Activision was to pay a total non refundable, fully recoupable advance of $8.5M US for the initial game, as set out in Exhibit A., the Milestone Schedule, and then negotiate in good faith the advances for the second and third games. But the advances for each of the second and third games would not exceed the advance paid on the initial game (10.1).

Chris & Dave: Section 10.1 sets a maximum on the advances, but no minimum. If the parties have a good relationship, then this is not a problem. But if the relationship is rocky, negotiating a large advance for the next game could be more difficult.

Tom: Additional advances could be added to the recoupable advances to be deducted from the Developer’s royalties if Activision had to pay another developer to provide work on the Games (10.2). The negotiation for the advances for the second and third Games will commence eight weeks prior to the completion date for the game then in development.

If the negotiations can not be completed in time, Activision agreed to make “bridge funding” payments, deemed Additional Advances on the future games, to allow Spark to retain its key personnel and maintain operations through the negotiation period (10.3). All Advances were fully recoupable from developer’s royalties and cross-collateralized across all platforms for each Game. But Advances can only be recouped from the royalties from the Game for which they are advanced (10.4).

Chris & Dave: The definition of “Advance” includes licensing fees paid by Activision to license third-party software and all of Activision’s costs to complete development. Part of Spark’s complaint is that these costs were substantial, and in Sprark’s view, excessive.

Tom: Royalty Rates - There are escalating royalties for each sold, or licensed, Game units from 20% up to 35% with 5% increase at 1,000,000 units and each 1,000,000 unit level thereafter up to 3,000,000+ (11.1). The “Adjusted Gross Invoice” amount is defined as the gross amount from sales and licenses, less the usual taxes, customer reimbursements, promotional amounts for discounts, rebates ad promotional allowances known at DFI (Deductions from Invoices) and coop (Cooperating Advertising Expenditures), cost of goods, first and third party royalties and license fees, returns, price protection and the return reserve.

Chris & Dave: These broad carve-outs from the definition of net sales significantly reduce Spark’s chances of ever seeing any royalties. Many developers try to avoid or limit co-op advertising and other marketing expenses because they can be significant and virtually anything can be classified as marketing (if it’s not classified as part of the Cost of Goods).

Tom: “Cost of Goods” is defined as the cost of materials, manufacturing, packaging, replication, and delivery, including freight and fulfillment charges (11.2).

Chris & Dave: This definition is typical, but some developers negotiate a fixed or maximum deduction for the Cost of Goods.

Tom: The return reserve is set at 20% of each quarterly statement and paid out after a 12 month (4 quarter) period (11.3). Spark also was to receive a 10% passive royalty on any ports of the Games by any other developer, subject to the same recoupment (11.4). Spark also received passive 10% royalties on any non-software ancillary products such as books, comics, movies, lunchboxes, action figures based on their original IP in the Game, except for hint books and strategy guides (11.5). Hint books and Strategy guides also yield a 10% passive royalty to Spark, provided that they assist and cooperate in the creation of such materials (11.6).

Tom: For purposes of Spark’s royalties, retail sales by Activision will be booked when invoiced (11.7), license revenue will be booked to Spark’s royalty account on actual receipt (11.8), foreign sales are credited at the then current exchange rate and booked when received (11.9). Spark is responsible for any tax on its royalties (11.10). If their Game is packaged with other Activision games, the proportionate royalty attributable to Spark’s Game will be based a ratio determined by the initial retail price of the games packaged together (11.11). There is no royalty due on promotional copies of the Game distributed fee of charge or inventory clearance if discounted to less than 40% of the initial retail price (11.12).

Chris & Dave: The inventory clearance clause greatly favors Activision. The better approach for Spark would be for Activision to pay royalties on the discounted price, as long as that price exceeds the cost of the goods.

Tom: Payments. Royalty statements are due 60 days after the end of each quarter along with any payment due, less appropriate deductions and recoupment (12.1). Developer Audit are limited to once a year and for a period of 12 months after each statement on 15 days notice at developer’s expense.

Chris & Dave: The 12-month time restriction is short. It’s understandable that Activision doesn’t want to dig up years of records for an audit; however, Activision must keep those records for several years anyway (for tax purposes). Audits are expensive, so most developers can’t do them every year. One compromise would be to allow the developer to audit previous years if an audit of the current year discloses a discrepancy of more than 5%.

Tom: If the audit reveals more than a 5% shortfall in payments to the developer, Activision pays for the audit (12.2). Royalty statements are deemed accepted if not objected to within 12 months (12.3). Any CPA engaged for an audit can not be compensated on any sort of contingent or other value added basis (12.4). The Audit accountant is required to sign a statement affirming that he is not being compensated on a contingent basis and also agreeing to provide copies of all his reports and work sheets to Activision, regardless of the result (12.5). So, in the unlikely event that an overpayment occurred, Spark could actually take a hit as a result of exercising its audit rights.

Chris & Dave: Section 12.5 contains an interesting typo. It refers to “Infinity”, which is presumably Infinity Ward, the developer Activision acquired in 2003. This suggests that the Spark agreement was based (at least in part) on Infinity Ward’s 2002 development agreement with Activision.

Tom: Marketing and Distribution. Activision is responsible for all marketing and promotional aspects of the Game (13.1) and agreed to a minimum of $2,000,000 commitment to marketing and promotional costs related to the initial Game (13.2). Spark was required to cooperate with the marketing and promotional efforts by conferring with Activision, doing interviews and press tours, doing photographs and artwork under Activision's direction, promoting the Games online, All media contact with Spark are required to be cleared through Activision (13.3). Activision retained sole discretion regarding the pricing of the Games (13.4). Spark was required, as part of the required milestone deliverables, to provide various screen shots, graphic images, character sketches, illustrations of weapons, vehicles, buildings and environments, and a hi-rez magazine cover art (13.5). Of course, Activision makes no warranty that the Game will be successfully marketed or that its marketing efforts on this Game will be on par with its other titles (13.6).

Chris & Dave: Activision claimed there were significant delays and additional costs in developing the game, which would have made the game much more expensive to successfully market. Accordingly, Activision found it difficult to justify spending more on marketing.

Tom: Credits and Notices. Activision agreed to give Spark appropriate credit for the Games by placing the Spark logo on the box and in advertising and promotional materials, except television (14.1).

Chris & Dave: The credit clause is good from Spark’s perspective. It’s more comprehensive than you’ll often see. This would have been important to Spark as a new company because Spark did not have a well-known brand at the time the deal was struck. Of course, a lawsuit can do the trick too!

Tom: Spark also was to receive 100 free copies or each Game or one for each individual in the Development team identified in the credits and Spark could buy additional units at cost, but could not under any circumstances sell them (14.2). Spark was also allowed to use the title, Trademarks and artwork in its portfolio and for promotional purposes on its web site (14.3).

Tom: Representations and Warranties. Spark provided the usual studio warranties to Activision that it had the authority to enter into the agreement (15.1.1), that the execution of the agreement is authorized and enforceable (15.1.2), that no other company or person has any legal interest in the Game (15.1.3), that the idea and works in the Games are the original works of Spark (15.1.4), that the Games do not infringe any third party IP and that Spark will correct, at its own expense, any inadvertent infringements (15.1.5), that any in formation used in the creation of the Games, not supplied by Activision, that is derived from third parties will be with written authorization (15.1.6), that Spark has the experience and expertise necessary to make the Games (15.1.7), and that Spark will at all times adhere to any publishing or tool agreements related to the development of the Games (15.1.8). Activision warranted that it has the power and authority to enter into the agreement (15.2.a), that it has the corporate authority to enter the agreement as a binding and enforceable agreement (15.2.b), that all ideas and IP provided by Activision in conjunction with the development of the Games is owned or properly licensed by Activision (15.2.c).

Chris & Dave: These representations and warranties were meant to protect Activision from exactly the types of claims EA leveled against Spark regarding theft of trade secrets and confidential information. Despite the contractual protection that these representations and warranties gave Activision, Activision made a business decision to help defend Spark against EA’s claims.

Tom: Indemnification. Spark agreed to indemnify Activision against any and all losses from any breach of the agreement or of the above warranties (16.1).

Chris & Dave: Indemnities are often useless to publishers if the developer has few assets. Activision could get more comfort by requiring Spark to maintain liability insurance, but insurance is often prohibitively expensive.

Tom: Activision similarly indemnified Spark from any breach of the agreement or Activision’s warranties (16.2). The procedure to be followed related to the indemnification are laid out in detail (16.3). Activision had the right to extend Spark’s representations and warranties to appropriate third parties and Spark would then be directly liable to such third parties (16.4).

Chris & Dave: This is unusual and it opens up Spark to huge potential liability.

Tom: Activision had the right to withhold payments from Spark if any indemnified claims were made by third parties until Activision recovered its costs of such indemnification or Spark provided reasonable assurances that it could pay the costs (16.5).

Tom: The term of this agreement is for the duration of the three games covered by it (17.1). Activision retained the right to cancel for convenience with specific additional payments and credits depending on the stage of game development at the time that right is executed (17.2). Activision’s total exposure for a termination for convenience of any single Game is the completed milestone payments and a possible $500,000.00 cancellation fee if the game is finished and in playable form when cancelled (17.3).

Any Material Breach not cured within 30 days is the basis for termination “for cause” by the non breaching party (17.4). Oddly enough, if Spark terminates for a material breach by Activision, the payments to Spark are payments for the delivered and approved milestones and a pro rata payment for the then partially completed milestone but no $500,000 extra payment similar to what is included with the “termination for convenience” provision above for a playable product. If the Game is in the distribution pipeline being sold, then Spark also receives royalties.

But, if the payments are made, Spark must continue to support the Game (17.5). If terminated by Activision for a material breach by Spark, the advances already paid are non-refundable, provided that Spark complies with the following section (17.6) Spark is required to deliver all work in progress, including all source code in order to receive the payments under the prior section.

This provision even requires Spark to allow someone from Activision to come onsite to supervise the transfer of all assets (17.7). For some unknown reason the survivability of certain provisions, including portions of this section is included here, instead of in the General Provisions later in the contract and it is numbered wrong too (another 17.7). Looks like even the heavy weight lawyers at Activision screw up some times.

Chris & Dave: Not surprisingly, the termination clauses allow Activision to terminate the agreement for any reason or for no reason (“for convenience”). If Activision terminates for convenience, Activision must pay a cancellation fee, but gets to keep the IP. This is typical in game development agreements, although some developers are able to negotiate the right to complete the game with a new publisher after termination for convenience, provided that the developer reimburses the first publisher over a period of time for the amounts the developer received from the first publisher.

Also not surprisingly, the termination for cause provisions don’t entitle Spark to a cancellation fee. That’s why developers usually want a clause in the agreement to say that their late delivery is not a material breach of the contract if the lateness was caused by the publisher (see our comments on section 6). Typical delays are late feedback on milestones, requiring additional work that’s outside the scope of the design documents, failing to provide assets and licenses required to develop the game, and failing to pay advances on time.

Tom: Confidentiality. The parties agree to keep all confidential information of the other party secret, except that Activision had the right to share the Game Design Document with third parties, which one would assume meant for marketing and distribution purposes, though it does not limit its distribution. As usual, the terms of the agreement itself are included as being confidential (18.1). The details of keeping the proprietary information secret is set out in detail (18.2). And the usual statutory exceptions to the release of information that has become public, previously released by either party, does no include proprietary information or was independently developed prior to the agreement is set out (18.3). Within three days after the termination of the Agreement each party was required to return all confidential materials and all copies of it (18.4). Of course, Spark was required to have all of its employees sign a confidentiality agreement consistent with this section (18.5).

Tom: Pretty much standard General provisions are also set out including references to Amendments (19.1), Governing Law (19.2), Severability (19.3), Headings (19.4), Notices (19.5), Integration (19.6), Waiver (19.7), Presumptions (19.8), Remedies (19. 9), Assignment (19.10), Counterparts (19.11), Injunctive Relief (19.12), Attorney’s fees (19.13), and Independent Contractor Status (19.14).

Chris & Dave: At law, if there is any uncertainty in a contract, the courts will sometimes give one party the benefit of the doubt if the other party drafted the contract. Section 19.8 tries to avoid this by saying that both parties participated in drafting the Agreement. It’s typical to include this type of clause in a development agreement, but it always gives us a good chuckle—especially when one party is a large publisher and the other is a new company.

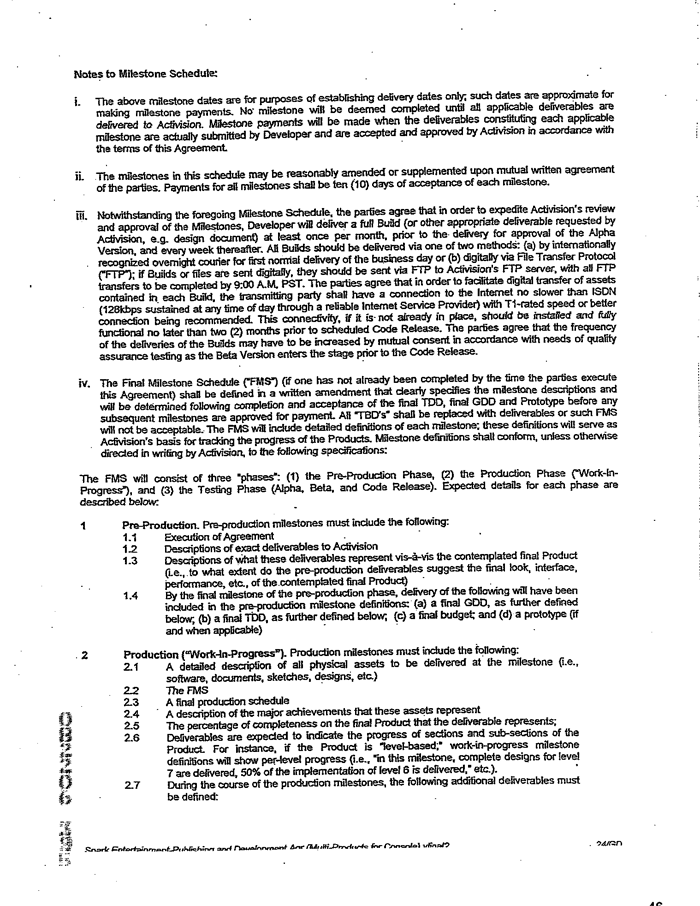

Tom: Milestone Schedule for First Project. Payments totaling $8.5M USD are spread over the initial game milestones. Since these schedules are incorporated into the Agreement, the Notes to this milestone schedule are as important as the other provisions of the agreement. Here the requirement of approval before payment is reiterated.

Also Spark is required to do monthly code dumps to Activision throughout the progress of the Game pre-Alpha, and then weekly builds thereafter. It also includes Activision’s detailed requirements for the Final Milestone Schedule (FMS), Technical Design Document (TDD) and Game Design Document (GDD) that are very informative. I recommend anyone serious about working with a major publisher like Activision or in making AAA titles take a close look at these notes because there is a wealth of information in them.

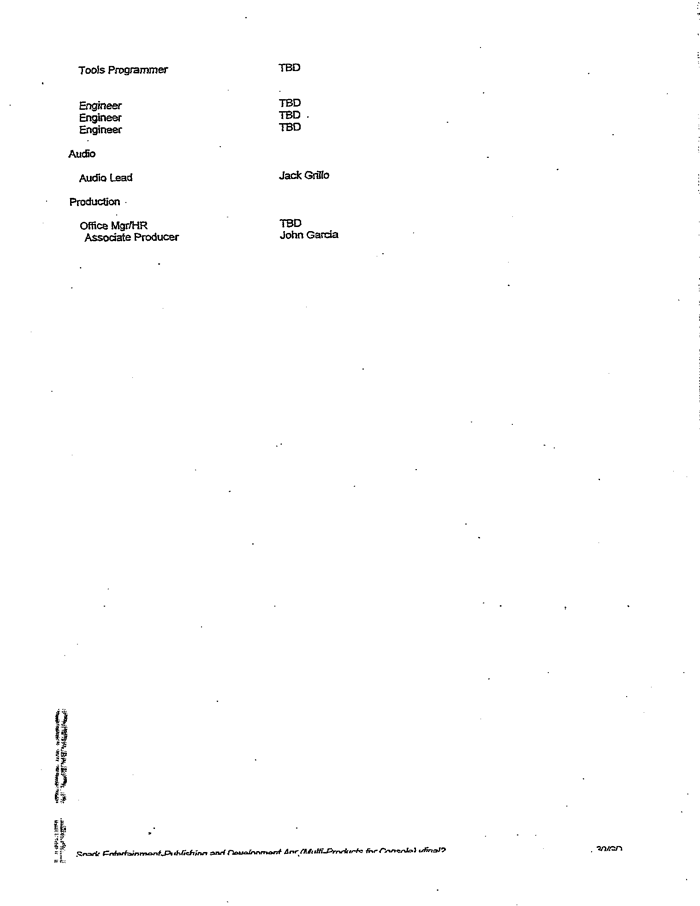

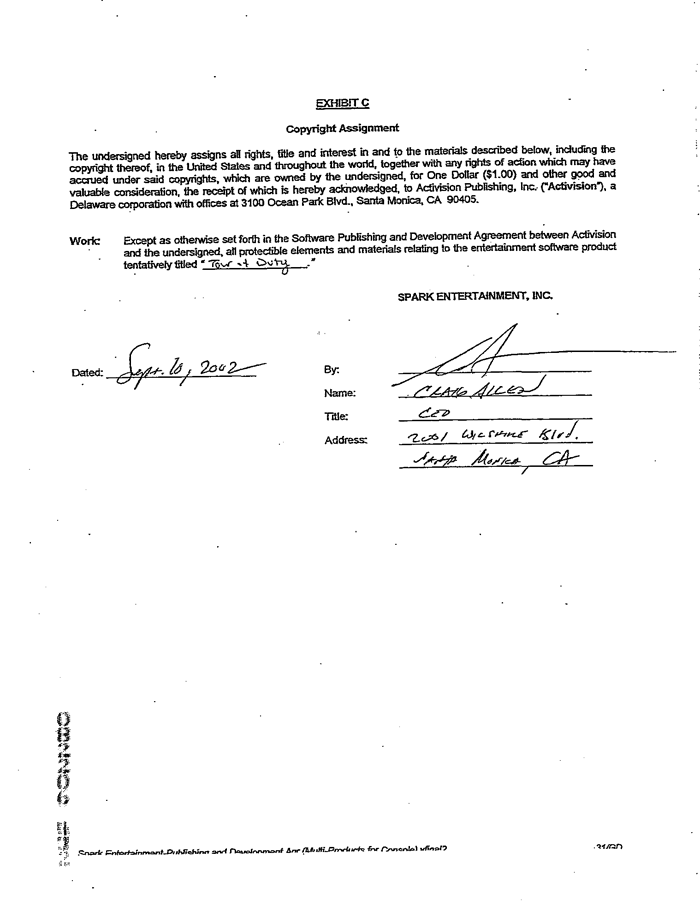

Tom: The remaining Exhibits - Key Employees (Exhibit B), Copyright Assignment (Exhibit C) and Activision Development Tools (Exhibit D) are self explanatory.

Tom: Well, I hope you enjoyed this little adventure into the wonderful world of big time publishing. As you may have guessed from the fact that there is a pending law suit, the execution of the contract did no go as planned…but that’s another story.

My personal best wishes to you all for a kick-ass New Year. May all your games get a 90+ metacritic score and may all your royalty checks be fat!

Til Next time…GL & HF!

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like