Licensing music, from individual tracks to adaptive scores

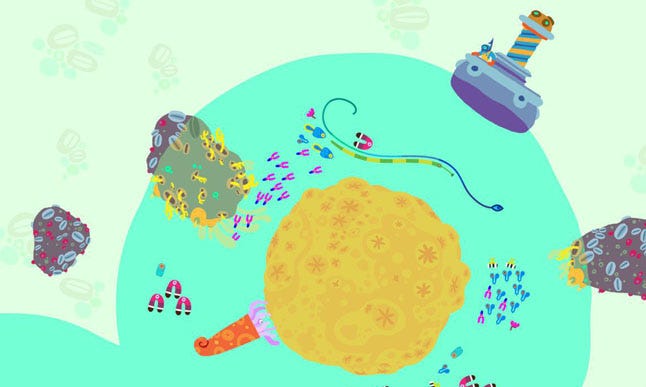

From the excellent soundtrack of OlliOlli to the bespoke, adaptive scores of Hohokum, we look at what's involved in collaborating with artists.

Finding the right music for your game is by no means an easy feat. The overlap between design and composition share a few parallels, but by and large they’re fairly far apart, even if they are inextricably linked. One supports the other, the music plucking the emotional strings while the mechanics of the game work at the more tangible loop of fun and reward.

Invariably, marrying the perfect soundtrack to a game requires bringing in outside help, be it a composer to make an original track, or licensing something already out there that encapsulates exactly the kind of mood that you’re going for.

We recently talked to Simon Bennet of Roll7 about how, even when you think you know what you’re going for in terms of licensing music, you’re not always right, when the soundtrack for OlliOlli took a sharp left turn away from punk rock and into the more relaxed and frustration-diffusing avenues of electronic music.

For all three of Roll7’s games, OlliOlli, OlliOlli2, and Not a Hero, the developer has sourced their music from existing tracks, putting together what are essentially extended compilation albums that accompany the levels and mechanics of their games. Being a three-person developer in the South of London, that means that they’ve, by necessity, set their sights on musicians in a similar position to them; by and large independent, pushing themselves out digitally through services like Bandcamp and Spotify.

"It wasn’t as much of an uphill struggle as I think we might have thought it was going to be."

“If you’re clever about it and you pick only independent artists,” Bennet tells me, “and you’re scouring Bandcamp and looking in those avenues, you’re going to find people who are mostly without a label, who probably don’t even gig, and they’re looking for any kind of revenue. Because of that you’re able to get them on your contractual terms, so you’re not wrangling for anything. At that level it’s kind of just, ‘Okay, cool, you can have the track. It’s available for free online anyway.’ So you help their art live on somewhere else.”

By and large, that’s what Roll7 has done with its games, focusing on the genres of IDM, dance and electronica for OlliOlli and OlliOlli2, and more chiptune-influenced music for Not a Hero. Artists like Dorian Concept, Tobacco, Slugabed, and Lone have featured across the games, and while they’re by no means small, they are approachable.

“When we spoke to artists directly, they would say, ‘That sounds awesome. Cool,’” Bennet continues. “Not only that, but they’d be interested because either they skated when they were growing up and listened to all the music associated with that, and they’d love to have their music do the same now, or they were absolute computer nuts, really into computer games, and it was their dream to have their music in a game. It wasn’t as much of an uphill struggle as I think we might have thought it was going to be.”

Which isn’t to say that it was all smooth sailing, as not only were there various different legalities that Roll7 needed to consider, but some of the tracks had their own hiccups when it came to obtaining the rights to use the track in the game.

“It still is about hunting those people down. We’ve got one track on the OlliOlli2 soundtrack that I’m most proud of because it was my favourite track of all of last year, which is ‘Shoulda Known’, the Ganz remix of the Louis Futon track. We literally only signed the contract for it last week, but we had been in negotiations for the last six months, having to get all of the different parties to sign up. There was a guy in Amsterdam who hadn’t got back to us for three months. It was so difficult because it was a remix, and there were so many people involved. Ultimately it’s not a process you would necessarily go through if you weren’t a little bit OCD about music.”

In regards to the legalities, there are a few things to consider, and a few things Bennet and Roll7 learned after putting together the soundtrack on OlliOlli.

"The main thing with any kind of contract is to make sure that they give you indemnity around any issues surrounding copyright."

“The main thing with any kind of contract is to make sure that they give you indemnity around any issues surrounding copyright. If a dance act has used a sample and you’re not aware of it because it’s embedded somewhere in the track, you need to be careful. If you have an indemnity from those artists where they agree that all the composition that they give you is their own, and if any of it is found not to be, it’s on them. That’s a helpful one.

“What I wish we’d done with OlliOlli 1 was actually agreed terms around the soundtrack, and selling on that soundtrack, at the point of doing it. Because we just licensed for the game, and even though everyone said they were up for doing a soundtrack, we just didn’t get it into that same contract. That’s something Devolver have had to change up for Hotline Miami, because I know they’re doing a physical release for the Hotline Miami 2 soundtrack.”

In terms of putting together a licensed soundtrack, then, things are fairly straightforward. You contact the artists, you put together a solid contract and you make sure that you’re covered for all reasonable eventualities. And when you’re making a game like OlliOlli, where each level is designed to be played in short bursts, it makes sense to grab the tracks you want and just tie them to specific levels.

However, when it comes to a more extended experience, something that persists beyond the standard three or four minutes that a song lasts, it gets a little less simple to just license a track and put it in the game. For example, with Honeyslug’s Hohokum, which has an extensive soundtrack filled with prominent electronic artists, a much more involved relationship with the artists was required.

“Honeyslug came to use with a prototype and some early art, and they had a bunch of music temped into the game, from cool ambient material to actually what turned out to be a bunch of stuff that happened to be on Ghostly’s catalogue," says Alex Hackford, a senior A&R and music scupervisor at Sony. Hackford was in charge of the music for Honeslug's Hohokum, and he worked with multi-discipline design house and record label Ghostly on the game's soundtrack.

“It was one of those things where, at SCEA, our job is just to facilitate whatever artistic vision the developers and creators have, obviously within budgetary scope. I contacted Ghostly, and we put together a wish-list of stuff together. I don’t actually think Honeyslug had any idea that the music they’d temped in could be artists who were actually willing to collaborate on the game. So it was mostly just being in the right place at the right time, and having a label that is willing to work with us as much as Ghostly.”

The result of this collaboration is a widely expansive adaptive score for Hohokum, with over a dozen different artists all making tracks that alter and change depending on how you interact with Hohokum’s many different levels. Some were based on existing recordings, but plenty were original songs mixed in as well. It’s hardly unusual for a game’s soundtrack to be dynamic in this way, but to have so many different artists all involved was no mean organizational feat.

“On Ghostly’s and the artists’ behalf, everyone was really excited to be involved,” says Jeremy Peters, the director of Creative Licensing and Business Affairs for Ghostly. “Being in charge of both the mastering and the publishing really gave us a lot of freedom to do these creative things, and allows us to have our artists write these new songs, and we could do a lot of really creative stuff around this world that you’re enveloped in.”

"With electronic artists a lot of this stuff is in that box, and can be tweaked fairly easily."

Something that both Roll7’s games and Hohokum share when it comes to their music is the genre that they’re operating in, and it’s something that’s consistently popular across both the indie and AAA space, although more in the former than the latter. Electronic music is incredibly well suited to games, not only in the way that it sounds, but also in the way it’s created.

“It’s really helpful that a lot of the Ghostly artists write in a box.” Hackford explains. “About 90 percent of my job is just finding the right artists, and explaining our needs clearly and creating a plan for an adaptive score that’s distilled in a way that artists can understand. Ghostly’s artists compose, they use Pro Tools, they use various other programs that let them see stems and understand how things get parsed out, or need to loop or blend.

“If you want to have a rock band create a demo for a specific part of a specific game, they have to go into a recording both and sit down and play it. And if you want changes, they have to go back, sit there, get four or five people in a room, replay, do the whole overdub and additional work. Whereas with electronic artists a lot of this stuff is in that box, and can be tweaked fairly easily. By and large it’s usually one person versus four or five people who have toget into a room. The artistic work is the same, but what changes is the ease and means of production.”

The other commonality across all the people I spoke to was just how deceptively simple it was to approach this kind of agreement in the first place. By and large the artists involved were actively excited to be doing the work, even when there was a label involved as an intermediary. To that end, I asked Peters how best to approach a record label.

“We’re getting hit by a lot of stuff at once, and the artists are as well, so if I get a very clear offer, detailing the budget, the offer, what the game is and what they need, all at once, I can just say, ‘Hey, are you interested in this?’ to the artists, and it can happen very quickly. If that initial courting process is very drawn out, those are the things that sometimes fall off to the wayside, because the artists get asked to do something concrete, like writing for an advertisement.”

Similarly, Hackford didn’t waste any time getting to the point when asked for advice. “What I would say for indie developers is that having someone to vet and really put together a one-sheet request that’s concise and clear will make everybody’s job a lot easier. Understanding the rights you need and being very clear how adaptive the score is going to be, what assets you need delivered, I think those kinds of things from a developer perspective are invaluable. It’s a very cheap contractor that you can bring on for a very limited term.”

Which gets back to what Simon Bennet was saying in regards to indemnity. Whatever the cost is to get a professional and water-tight contract together is going to pay off in the long run, even if it is an initial expense.

As for Bennet himself, his advice regards the work involved in putting together the soundtrack itself: “If you’re 100 percent sure this is the route you want to go down, it’s time-consuming, it’s going to require a watertight contract, but at the end you’re going to get exactly what you wanted.

"If you’ve got the capacity to do it and it works for your project, you should go for it. If you’re able to license the music that you like, it is exactly what you want, there’s no question. If you believe in the project that you’re doing, and you can project that onto whoever you’re targeting to license the music from, and explain to them why you love their track. It needs to be a heartfelt plea. I’ve sent some really heartfelt emails out about some electronic dance music, but I think that’s what you need.”

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like

.jpeg?width=700&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)