Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

Voice acting is a surprisingly vital part of character-based game creation - and Gamasutra talks to Sony dialog manager deBeer on his work aiding titles from the God of War series to Uncharted: Drake's Fortune.

As the discussion of the improvement of storytelling in games heats up, one of the most crucial factors to address is the acting that carries those stories.

Just as the artists on the team must strive to create believable and compelling characters, and writers must pen dialog that holds players' attention, the voice actors who lend those characters their voices must fulfill the quality of those digital performances.

Here, SCEA Foster City dialog manager Greg deBeer discusses the evolution of the art, taking into consideration all facets of how these dialog-based experiences are created. He looks toward the future of the art, and describes Sony's techniques to improve its cinematic storytelling -- seen in games such as the God of War series and Uncharted: Drake's Fortune.

Which titles are you in charge of? Are you in charge of all dialog for Sony's U.S. studios?

Greg deBeer: The dialog group is a service group within Sony Computer Entertainment. Our internal and external production titles have the opportunity to use the group for any one of our services. There's the dialog group, there's motion capture, there's our sound group, cinematics group, and multimedia group, which does a lot of behind-the-scenes stuff.

Probably, I'd say 80 percent of the titles that SCEA is involved with -- either through internal or external studios -- we help out in some capacity with the dialog. That includes the SOCOM franchise, the God of War franchise... we helped Naughty Dog with Uncharted, some of the sports games...

I know some of the audio stuff is done down in San Diego, at that studio.

GD: Yeah. We have audio people in Foster City, Santa Monica, and San Diego, and we have dialog people working in Foster City and Santa Monica at the moment within my group, and in San Diego, there are sports-specific dialog designers that report to a different manager down there.

Dialog is something that I've been interested in, because it used to be, in my opinion, really bad, and it has been slowly getting better, but it's still got a ways to go, depending on title to title. God of War was a quite good one, though. To start, how long have you been doing this?

GD: When I first started in the industry at a company called NovaLogic in '99, I was hired as a sound designer, but I came from an art school -- Cal Arts. I was at Cal Arts, and I got onto the middle of a project, and sound design was almost done, and they still needed to do some dialog points, so they put me on that. So that was really my first trial by fire experience with dialog.

We then started up another project called Tachyon: The Fringe, and that was the company's first dialog-heavy, truly creative... it was a military-style [simulation game] company, and this was a very creative venture for them, and they needed a lot of very specific actors for it.

NovaLogic's Tachyon: The Fringe

Having gone to Cal Arts, I was friends with a lot of people in the theater department, and I was able to get them in quickly and relatively easily and relatively cheaply. They just wanted to get their names out there and get some credits. So that was my first relatively large project with casting and directing and getting people involved.

So I've been doing it for I guess about eight years now, and yeah, it's been getting a lot better. I think the biggest shift that a lot of people agree with is that there's a steady trend away from the thought that anybody can do dialog.

When I first started even at Sony, most of the games were handled by people at the office. We'd find people like, "Oh yeah, you did some voices for that punching game, so why don't you come over and take a half-day off from doing level design and do a couple of voices for us?" We slowly realized that we couldn't do that anymore. As story and dialog became more integral to games, we had to move towards professional talent, and that's what we've been doing.

Do you find that -- this is a loaded question -- that you get better results from voice actors, or actors?

GD: Absolutely voice actors. In general, my recommendation is to stay away from celebrity talent. My personal reasoning for that -- which I've discussed with a lot of people, and a lot of people disagree with me -- is for me, hearing an identifiable celebrity voice takes you away from the game. Instead of being immersed in this environment with these characters who are supposed to be a part of whatever world you're playing, you say, "Oh, I recognize that voice," and it brings you back into the real world. It's a very disruptive experience for me personally.

I also find, in many cases, celebrities are used to a very specific way of being dealt with and dealing with production, and voice over is very different from that. And game voice over is different from just straight animation or ADR or something in a film setting. There are some actors that can handle it very well, but I've found that more often than not, the more exposure they've had in the film world, the less they are able to cope in these situations.

Yeah, I agree with your assessment myself, partially because I wonder how seriously film actors will approach being in a game. Will they think of it as something to just bang out in a day, or is it more like, "Okay, I've got to get into my character?"

GD: Yeah, I think it's hard for someone who's done a lot of film and isn't really mentally willing or able to make that shift over to games, because they just aren't as invested in the character as they would be in the film. They're not in-costume. They're not on-set. They have to get into the character in a very short period of time, and without the weeks and months of rehearsals and preps and script-readings, it's a very difficult thing to do.

You need to have that very specific mindset to do that, and someone who is a professional voice actor, who basically does most of their work in games, is going to be much better at doing that.

I'm curious to know your opinion of finding an actor and then saying, "I want you to do this kind of voice," versus finding the person who has the kind of voice that you think is fitting the character already. Where do you fall on that?

GD: Are you talking just in terms of casting?

In terms of casting, yes.

GD: I'm always for having an extensive casting for any of your characters to bring in, because you just don't know who's out there. Working with a casting director, or working with people who are up-and-coming in the industry... there's always people working, or coming out of school, or training or whatever they're doing, and they're trying to break into the industry.

And sure, nine times out of ten, they're not necessarily ready for prime time, but there is always that one-out-of-ten actor who's just going to be something you've never heard before, and if you can find a person who hasn't been in any other game, you'll have a unique sound to your game, you know?

It's pretty amazing how people have these ideas in their head of what they want from the character, just because it's in the general game gestalt. We'll do a casting session, and they won't necessarily look at the cast list from another game, but we'll end up with the same people in the game, because they have this stereotype in their head. Most of our games have maybe a 50 percent overlap with another game's voice actors.

So do you think it's better to find one person who has a range, or to find a natural voice that makes the character?

GD: Natural voice is always going to win out for me, especially for a lead character. A lot of times, because of financial considerations, we like finding people who can do ranges, so we can bring in one actor and get several parts out of him in one session. That's good for spending less time in the studio and getting the most that we can out of an actor. So there are places for both.

If you have a main actor who's playing your main character, sure they might have to pitch their voice up or down or rough it up a bit, but they're still going to have the vocal quality of your main character, so you don't want to have your main character talking essentially to himself with a disguised voice, because generally that's going to come through no matter how talented the actor is.

It's extremely humorous when that happens, but not in a good way.

GD: Yeah, you can say, "Ha ha, look what you guys did!" but you certainly don't want people doing that to your game.

No, no. One of my personal pet peeves has been accents which are not natural. What can you do about that when you have a budget consideration? Is there anything that you can do?

GD: Well for us, we being Sony, we're in the fortunate position of having offices overseas, so if we really need to get a specific accent, we'll either cast in Los Angeles -- spread a wide net and see if we can find a native speaker in LA -- or we can just go to, say, France, and go find someone who can speak English and work with our compatriots over there and say, "Hey, we're looking," and they can write it for us, too. That gives us the advantage of having more of an understanding of what's in the current mindset of the French culture.

It's always changing, what's current and what's in. For a smaller organization or business... just the tried and true, spread your net far and wide. Meet people who speak different languages and say, "Hey, do you have any friends who come from France?" There's a lot of people here in the States who have a wide variety of performance ability. You can always find the people, it's just a question of spending the time to do it.

That calls to mind for me [Sony-published PSP title] Jeanne D'Arc, which... no offense if you worked on it, because I don't know if you did...

GD: I didn't, no. Our group helped out a little bit.

Level 5/Sony's Jeanne D'Arc

Because the faked French accents made it difficult for me to watch the cutscenes. But one thing I've learned talking to people about this over the years and seeing fan reactions, is that I'm in the minority, in terms of caring about how the dialog sounds and how real and gripping it can be. Do you feel like a lot of people notice if it's way better or worse?

GD: It's one of those things. People definitely notice if it's worse. When the dialog's really good... reviews more and more now are trying to be more comprehensive in hitting music, sound design, and dialog, or at least dedicate a sentence or two to it, so getting positive reviews on dialog puts you in the positive feedback cycle of encouraging producers to have better dialog. So people do notice, but it's an underappreciated art, I think, generally.

Maybe rightly so. I don't know. I'm kind of two minds about it. Obviously, I'm very passionate about dialog and want the best we can get in our games, and I'm very partial to storytelling and story in general. That's why I play games. Shoot 'em-ups are not very appealing to me. I like character development, and seeing a story arc. But games are interactive experiences. They're about the gameplay.

If you're going to play a game, you don't want to see ten hours of cutscenes in your game, so dialog is very important, and it absolutely enhances the experience, but it isn't and maybe shouldn't be the first talking point in a review.

Games are often dealing with the hyper-fantastical. How do you deal with that, in terms of making something believable which doesn't actually exist?

GD: It really depends on the game. You can have a very hyper-fantastical environment, characters, and world, but they can still be intelligible. So a lot of rules of performance and direction and acting still apply. The actor needs to be aware of what they're in, and they need to be familiar with the vocabulary of the world at the time.

They need to be aware of what they're getting themselves into, so they don't stumble over their words, or even worse, we get into a recording session, and the actors see the script, and they pronounce it one way...or we'd written the script and haven't necessarily thought about it, and two days later, we get another actor in and they say it another way, and we're like, "Uhhh, I can't remember how they said it," or we forgot that the other actor said it another way, and when we get to production, we realize that people have said the same made-up word in two completely different ways, and that's just completely unacceptable.

It requires preparation on our part, it requires preparation on the actors' part, and it really depends on the nature of the game. So if we need to create monster sounds that are intelligible, then we need to work closely with the sound design department, and say, "Okay, here's some intelligible dialog, and now we need to figure out a way to make it work with your sound design elements."

Maybe we'll do some test cases first, so when we go into session, we'll know what type of direction we need to give the actor to make the processing easier.

We might need to say, "Okay, we'll need to be speeding you up a lot, because you're this pixie monster, so we actually need you to talk slowly in the session, so we have room to speed you up." Whatever it may be, it just depends on the constraints of the design.

Do you have any control over whether your dialog is going to be in cutscenes or in game? If you were to say, "You know, we don't really need to do this information here. It could flow much better if it came in this way..."

GD: To some extent. Our role with Sony is again, primarily, as a service group, so oftentimes we come into a process with the script mostly or fully written ahead of time. Then we'll get a script review and give comments, but it's certainly not anything that a producer has to take to heart. It's a recommendation process.

Sony's God of War II

What is your personal feeling about cutscene versus in-gameplay dialog? There are obviously places for both. When do you think each is the most appropriate, in terms of advancing story?

GD: That's a really loaded question. Again, it depends a lot on the game and how you're trying to promote. For God of War, the story is very cinematic. You're trying to present this story in a very specific way. You want very specific camera angles and reveals, and you want the dialog to happen in such a way that it has the most impact with regards to the visuals.

So when you're in that situation, it's much better to have it in an in-game cinematic, whereas if it's informational and it's not quite as tied to a very important camera sweep, then it's better for it to be in-game. I think the more in-game you can have, the better, because it is an interactive experience, but it just depends on what you're trying to do with it.

In terms of barks and things that happen frequently, what kind of advice do you give to the actors in terms of variation? I don't know if there's always room to have variation sometimes.

GD: Well, the more variation you can have, the better, especially with next-gen titles. With the huge amount of room we have on disc, there's no reason not to have as much variation as we can.

Advice to actors is that we'll generally say, "Here's a line. I want you to read it to us three times, and give us your own personal three different interpretations of it," and kind of leave it at that. Directing is always a fine line. It depends on how strong of an actor you have, but it's better to let the emotion come from inside the actor, as opposed to trying to force a performance onto an actor.

How much do you tell an actor what the mood of a character should be? I've heard a lot of actors will just show up and see the script for the first time, and it'll be hard to connect with the character.

GD: It is very hard, and that gets back to what we were saying about celebrities versus voice actors. A lot of this comes down to how well we've prepared. Sometimes we won't really have a script together until a day or two before the session, and there's not time to get the script out to the actor.

The ideal situation, of course, is to have the script done a week or two weeks before time, get it out to the casting director, get it out to the session director, and get it out to the actors a day or two before their session, so they can read it over and get that sense for themselves of the whole story.

It's great if we can get it in a movie script format -- a format that they're familiar with -- with scene settings and all that, but that's not always possible. When that's not possible, we do as much as we can in the session. We try to set aside fifteen or twenty minutes if we can. Obviously, we can't set aside the whole time, because we're trying to get through using a very large amount of voice recording, but we'll bring character art.

We'll have a producer there -- someone who's very passionate about the game -- explain the scenario, explain the mood, explain the theme, and explain the general arc. Then, when we're in session, we always have a professional voice over director that's familiar with the script that can speak the language of performance that can take a performance out of an actor without shaping it for them.

And we'll have the producer there, who can interface with the session director, who can get the, "Okay, this is what's happening in this scene." The director can take that and understand what needs to be said to the actor to get the performance out of the actor that's appropriate for the scene.

Where do you see dialog progressing from here? It's kind of a vague question. Where do you see it going? For example, (non-game) animation, over time, has evolved to become very stylized, and generally not naturalistic. Whereas movies are obviously very naturalistic. How do you see games going, in terms of those concerns?

GD: I think the evolution of dialog is going to be very, very tightly entwined with the evolution of game development, because dialog is so tied to how a story is presented, and how you interact with the environment.

There's not going to be leaps and bounds in terms of better performances. Obviously, there will hopefully be leaps and bounds for the lower-quality games, but we're getting the best talent that we can, and acting is... we can do sample resolution and bit depth, but we don't want overacting.

So the leaps and bounds in dialog is going to come from the implementation side. It's going to come from getting more resources to writing more variety. It's going to be in having multiple storylines. It's in having the ability to store that much data on the disc. It's getting to the point where we don't hear the same line every five minutes.

Maybe if you play a scene and you die and you have to replay the entire scene, we'll be able to have the same information presented, but maybe not in the exact same way, using slightly different files, and having multiple variations on the disc for everything in the game so it feels if not fresh -- because you're getting the same information, and you know what information you're getting -- at least it will not feel completely, strictly repetitive.

It's an interesting distinction, because it's a semi-artificial kind of variety, because it's still limited.

GD: Right. The goal is to feel like you're deja vu and you're hearing the conversation again, but you're not hearing a record player.

Can you mention a couple of games that you think have excelled in dialog in the last couple of years?

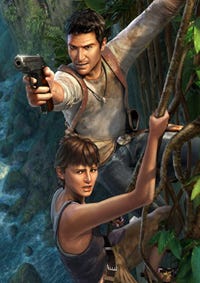

GD: One of my absolute favorite examples of dialog implementation right now is Uncharted: Drake's Fortune. I think they just did a phenomenal job of getting strong performances.

GD: One of my absolute favorite examples of dialog implementation right now is Uncharted: Drake's Fortune. I think they just did a phenomenal job of getting strong performances.

Really, they did some nice stuff, in terms of where they gave their information. They did a lot of stuff where you were having relatively long conversations while you were in the middle of gameplay, and interactions between characters where you didn't feel removed from the action.

It was happening as you were running through the jungle, or whatever. I thought that was really nice. It was a change from having constant action, action, action. It was like you get from this place to this place, and while you get there, exploring on your own, you're hearing something else that's happening.

Actually, one of the other things I see as possibly happening in the future for dialog is more... again, it depends on the game, but there's going to be more integration between motion capture and dialog. Right now, motion capture in general is taking off, more games are using it, and more triple-A games are going in and playing out their scenes like they do in real movies.

In the past, where you'd have hand animations or whatever, you'd have animations, and then you'd have your voice over and you'd play it on top of that. Whereas getting voice-over and the motion together in one session, while the quality... you don't get studio-quality recordings on a motion capture stage, because there's a lot of movement going on, and you've got big vents, and there's stuff blocking [the actors].

So we try to get boom mics, but it's never quite the same quality, so we end up having to do ADR, like the movies, but you're ADRing to a motion that is real from the set. I think that's going to be a big change. Again, it's not new. It's been happening for a while. But I think we're going to be seeing more and more of that.

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like