Game Design Deep Dive: VR cockpit audio in Gunjack 2: End of Shift

"A great deal of realistic audio is incorporated in the player�s cockpit; various alarms, diverse weapon sounds, dialogues, cockpit physical audio representation, and enemy fire impacts on the turret."

Deep Dive is an ongoing Gamasutra series with the goal of shedding light on specific design, art, or technical features within a video game, in order to show how seemingly simple, fundamental design decisions aren't really that simple at all.

Check out earlier installments, including creating believable crowds in Planet Coaster, achieving seamless branching in Watch Dogs 2’s Invasion of Privacy missions, and creating the intricate level design of Dishonored 2's Clockwork Mansion.

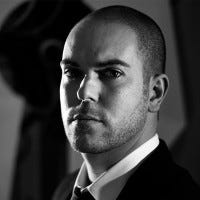

Who: Alex Riviere, Audio Director at CCP Shanghai

I’m Alex Riviere, Audio Director at CCP Shanghai. I joined CCP about a year ago to build, develop and lead the Audio Department of the Shanghai studio.

I graduated from an electronics and computer sciences university and then earned my master’s degree in sound design. I have worked in multiple audio industries in the past 10 years, starting my career as a Music Producer and Composer for Sony ATV Music Publishing France. After taking the reins of a post-production sound studio in China and founding my own game audio outsourcing company, I joined the CCP team as Audio Director.

I’ve been involved in many projects from record albums, commercials, documentaries and video games. Incredible franchises that I’ve had the good fortune to be involved in include Call of Duty, Final Fantasy, Transformers and Borderlands to name a few. Each project involved different aspects of audio such as design, direction, localization, voice production, and mixing.

Having collaborated with CCP as a contractor to handle the audio for Gunjack (Playstation VR, Oculus Rift, Samsung Gear VR and HTC Vive headsets), I was asked to join the team and lead the audio department for Gunjack 2: End of Shift (Google’s Daydream platform) and all other projects coming out of the Shanghai Studio.

What: The Cockpit Experience of Gunjack 2: End of Shift

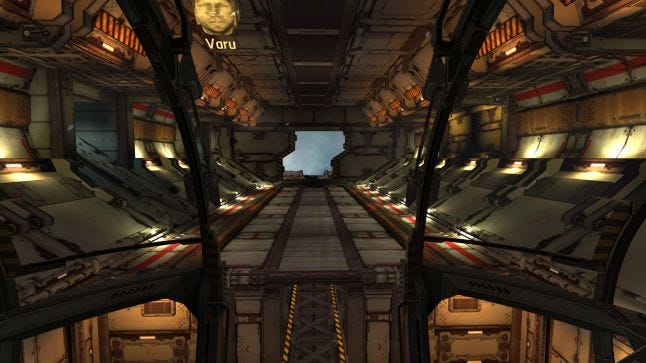

Gunjack 2: End of Shift is the sequel to the best-selling VR game Gunjack. Players take on the role of a turret operator (or Gunjack as they are called in-game), on the Kubera, the largest deep space mining rig of its kind. Gunjacks are tasked with defending the vessel from pirates, bandits, and anyone else looking to blow up the rig or steal the precious cargo.

"All the sound passes through an acoustic rendering of the cockpit, so that the player really has the sense of being a turret operator inside this specific physical space."

Because Gunjack 2: End of Shift is a VR game, it is vital to create a true sense of immersion in the gameplay experience. Intimate interaction is one of the most important things in VR, and your intimate zone would be 0 to 5 meters from the player character (first person sounds in our case).

That’s why our main audio feature is what we call the “Cockpit Experience”, the goal of which was to make the players feel physically present in their turret. Gunjacks are the last line of defense, so we really wanted the player to experience this overwhelming and ominous feeling.

We leveraged everything we learned from the first Gunjack game to further refine and enhance the Cockpit Experience and make it even better.

A great deal of realistic audio is incorporated in the player’s cockpit; from various alarms providing different levels of stress to the players based on the threat, to extremely detailed and diverse weapon sounds, dialogues, cockpit physical audio representation, and enemy fire impacts on the turret. All the sound passes through an acoustic rendering of the cockpit, so that the player really has the sense of being a turret operator inside this specific physical space.

One of the challenges we’ve faced is that we’ve been primarily creating sounds that do not exist in the real world, however our brains do already have a sense of what feels real. We therefore needed to create our assets from audio sources that exist in the real world.

Working with mechanical sounds usually gives a sense of credibility, it instantly feels “right” when we hear it for the first time. We needed to incorporate these sounds to match the world we've built, to seamlessly sell the experience.

"We incorporated auditory feedback so that as the player runs low on ammunition, the drier and more metallic the weapon sounds"

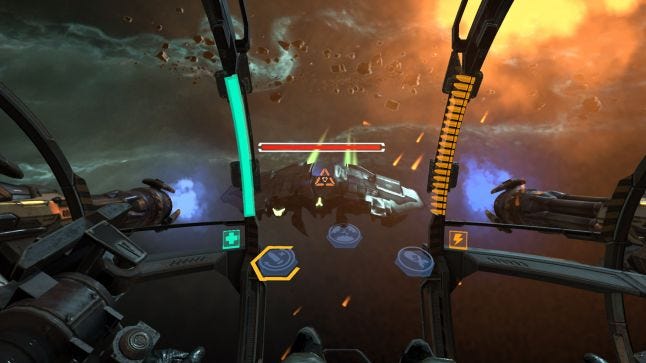

As a shooter game, one of the most obviously important aspects of gameplay is going to be the weapon’s sound design.

We want to keep players connected with their weapons and tools, so we’ve incorporated many different layers of control with game parameters to continually provide all the subtle feedback and variations to make that possible.

A perfect example would be the players’ main weapon, the autocannon. Since this is the weapon you spend the most time using, we’ve built literally all the audio mechanical aspects of it—the spinning barrels, reloading, adjustable firing systems, and so on. One of our learnings from the original Gunjack was that players lacked natural audio feedback to indicate they were running low on ammo.

It was important for us to truly immerse the player in the action. Thus, we incorporated auditory feedback so that as the player runs low on ammunition, the drier and more metallic the weapon sounds. This provides natural and tactically important audio feedback to the player to reload soon, or risk running out during combat.

Besides the critical gameplay information that needed to be carried by the audio, we also wanted to help drive the narrative of the game. We integrated most of the dialogue through a diegetic approach, where the sound source (com-link in this case) is visible on the screen and integrated into the cockpit environment. This allows us to use radio communication chatter to serve multiple purposes, such as seamlessly integrating tutorial instructions, providing gameplay tips and driving forward the storyline of the game.

"We integrated most of the dialogue through a diegetic approach, where the sound source (com-link in this case) is visible on the screen and integrated into the cockpit environment."

When we had completed all the sound coming from inside the cockpit, the next step was building audio feedback that reflects the physical response of the cockpit during combat.

A large enemy quickly flying by your cockpit will make it rattle, and firing missiles from the turret will make it shake. We very often had to implement these audio cues without any visual feedback (because adding camera shake in VR can make the player nauseous), so mixing to have them blend subtly into the overall first-person experience was essential.

Gunjack 2: End of Shift also features an all-new gameplay mechanic, the energy shield. The player is able to deploy the energy shield to block or even deflect enemies’ projectiles back at them. Besides the obvious shield sounds and audio behaviors with projectiles, we’ve used the fairly simple yet critical concept of sound propagation: absorption and diffraction of sounds due to the presence of energy shield.

In other terms, when a player activates their shield, every sound source behind the shield will be treated differently in terms of frequency and dynamic, as they are altered by the presence of the energy shield between the audio source and the player.

With all those details integrated into the cockpit, the last piece missing in the Cockpit Experience was the player’s character. We wanted to have audio available to engage with the players’ movements, however we were bound by the constraint that mobile VR movements are primarily limited to head motion and the controller’s movements.

"The last piece of the puzzle that makes you feel physically present in our virtual world was the sound of the player’s character moving in their chair during head movement."

After countless tests and iterations, the last piece of the puzzle that makes you feel physically present in our virtual world was the sound of the player’s character moving in their chair during head movement.

We spent a great deal of time in the recording studio to catch various sounds of a person shifting in their seat, such as clothed movement against leather or fabric and the mechanical sounds of chair squeaking that were convincing, believable, and subtle enough to blend nicely in our game soundscape.

For virtual reality, on a creative side, you often have to experiment without knowing if what you are doing will work, because audio and design for VR is still in its infancy. As an example, as soon as I was happy with the head movement audio feedback, I ran around the office and had different people try the game to see if they spotted the difference with the feedback added. No one did.

I submitted my changes and waited to see if QA would bug it. They did not. Once I explained to the rest of the team what piece I’ve added to the cockpit experience, often the answer was that they felt they were hearing themselves moving on their chair while playing the game. That was when I knew this worked perfectly.

Why?

In seated VR games, there is usually less interaction with the environment, so we have to produce audio effects without there necessarily being any visual feedback; we need to make it appear that there is more happening in the game than is presented visually. In our case, third-person sounds are used primarily to provide gameplay feedback (to help players understand what’s happening around them), while first-person sounds are our intimate zone.

Gunjack 2’s audio vision was to create a striking contrast between the industrial, patched together aspect of the cockpit, and the sonic signatures of the high-tech enemies flying around players. Creating a connection between the player and their cockpit was vital in the game development process to really bring the sci-fi shooter to life in this virtual world.

Result:

When developing games for new media, game developers from any disciplines should not be scared to think outside the box and take the necessary time to experiment. Creative solutions and processes are currently being developed for VR, and I am confident that developers will continue to learn and refine how to create the most amazing VR experiences.

In audio, and especially in VR audio, every single tiny detail counts, even the ones that seem insignificant. Audio is a critical medium to properly simulate a sense of presence in Virtual Worlds.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like

.jpeg?width=700&auto=webp&quality=80&disable=upscale)