Trending

Opinion: How will Project 2025 impact game developers?

The Heritage Foundation's manifesto for the possible next administration could do great harm to many, including large portions of the game development community.

What can the well-established techniques of other media teach developers about game audio? Exploring structure, dynamic range and other ways to put the 'sound' back into sound design.

Video game sound can often be perceived as a car-crash of sound effects, wall to wall music, and out of context or hard-to-understand dialogue. However, there are some well established artistic techniques within similar media, such as TV and Film sound, that can help allow for moments of relative calm which serve to intensify moments of subsequent chaos, without needing to turn everything up to 11 all the time.

This feature examines common examples of dynamics from horror cinema and how those rules can be adapted to game design and game audio in any genre through graphic visualisation and planning techniques.

'Design' is one of the most important areas of sound design, in that the sound designer needs to sit down, over the course of many planning meetings, with game designers and plot out and map the intended experience from start to finish.

This is done via each and every mission and cinematic and decide where the game needs to deliver the biggest impact, both from a macro-cosmic level for the entire game, and potentially a microcosmic level for each mission stage. This is, in effect, designing the dynamic range of the game experience and mapping where audio will follow that curve or any areas where audio needs to play against that curve.

Audio clearly needs to be involved in this planning process as music, sound and dialogue are some of the more potent tools for delivering subtlety and intensity in a game. This process is one of the many aspects of sound design that doesn't involve sitting in a studio designing sound effects and tuning game audio, it is potentially the most important to the integrity of the whole soundtrack, as it will dictate where music, fx and dialogue all need to work together with the game flow.

A wide dynamic range is often talked about in audio terms as very desirable, meaning amount of difference between the quietest and the loudest sounds. Something with no dynamic range cannot be experienced for very long before the viewer, or listener, becomes fatigued and reaches for the off-switch.

A game without a range of varied game-play moments and experiences for the player will more often than not result in a game soundtrack that has little or no dynamic range. Batman: Arkham Asylum and Dead Space are wonderful examples of games that have been carefully designed to have specific moments of calm, moments of silence, a mixture of stealth and combat as well as moments of intense action and resulting high volume sound, music and dialogue.

These games are wonderful examples of structured experience, and dynamics in both game-play and audio grow from structure and from the ability to control the intensity of the moment prior to an intense moment.

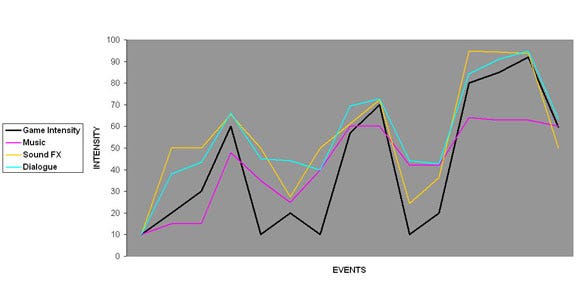

The dynamics of any game-play narrative can be easily plotted on a linear graph that only needs vague intensity measurements or gestures (fig 1). Each game-play element, mission or level can be plotted showing how the intended narrative intensity of that mission or event should feel over time. A curve can be applied to the map the intensity of each mission, each level and eventually the game structure as a whole.

Once a 'game intensity' curve has been drawn out, the separate audio elements, music, sound effects and dialogue can either play with the game intensity curve or play against it. This map can even be used to set up expectations in the matching of audio action to game-play action, and then break those rules as the narrative progresses to provide even further excitement and immersion in game-play.

Simple ways to think about the dynamics of audio are by looking at horror movie, or survival horror games that have successfully taken the intended game-play intensity and mapped audio onto and against these curves. Often leading with audio, the viewer's expectations are manipulated within the horror genre.

Silent, or extremely quiet moments where characters (players) are listening to the world around them often precede extremely loud and sudden violent moments in the horror movie genre. This is of course completely by design and always playful within the established conventions of this genre.

Survival horror games such as the excellent Silent Hill series have taken the way that sound leads and incorporated it into a variety of game-play elements. Non-diegetic sounds are used well in this mode of game to play to evoke the elements of unseen horrors within the player's imagination. Their use of visual darkness and fog effects is also exemplary within video games in allowing sound to develop and evoke an often never revealed visual world. Moments of near silence are followed by sudden and disturbing attacks from increasingly bizarre creatures.

While this genre in particular lends itself to these kinds of extreme dynamics, these are certainly ideas that can be picked up and used within all other game genres to help increase dynamic range.

A cleverly constructed montage of silence and sound has far more dramatic effect than the loudest of sounds in isolation. The structuring of how silence works in conjunction with sound, in a sequence, is similar to the film editing practices espoused by Eisenstein nearly a hundred years ago, in that expressive power is only gained when these elements are edited together and deliberately played against one another.

These techniques can be clearly heard in the horror genre of films and games. A lone teenager creeps through a creaky house at night, high pitched strings in the musical score build, a creaky sound is heard, phew it was only a cat, the strings stop and for a brief moment there is the silence of relief, then, in that moment where the audience is catching it's breath with relief, then the enemy strikes. It is in this way, playing with silence and tension, building and releasing, that helped forge and define the conventions, particularly in horror genre movies in the 1980's.

Racing games, open world games, non-horror FPS games can all learn from techniques in the narrative dynamics displayed in the survival horror genre. It is as simple as this... 'Precede very loud and intense moments with quiet and tense moments'.

In order to make an event seem really big, it makes sense that immediately preceding that event is a drop in both game-play action and an accompanying drop in sound levels; this will make the subsequent sonic barrage perceptually seem so much louder, even when in measured decibels it is not.

One all too common pitfall for games designers is that game-play dynamics are often never plotted out visually on a graph until the game production has been completed. If a simple dynamics curve is applied pertinent game-play elements, with some understanding of how to make things seem more intense by preceding them with low intensity moments, then sound, art and technology teams can use these curves in order to make critical planning, aesthetic and technical decisions that not only match the curves required by the game-play but that are able to deliver the intensity required when it is required, while also exposing the potential to play against these established expectations later in the game, thus magnifying their effects on the player's senses.

It is this ability to draw in the audience, or player, with sound where dynamics begin to be fully realized in an artistic way and the game becomes a cohesive structured experience. Without a suitably defined dynamic range game-play curve within which to do this, it can be a more difficult job than it needs to be to deliver the same high and low dynamic moments within a game as there already exists in filmic or classical musical structures.

One of the more interesting aspects of dynamics mapping is that the resolution of the events varies dramatically depending on the type of game experience that is being made.

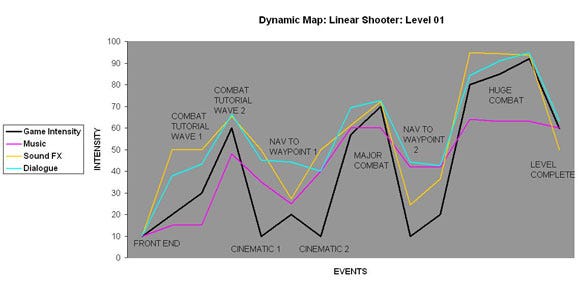

For example, a highly scripted, linear game-play experience such as Arkham Asylum, Gears of War, Bioshock et al, have a very high resolution of events and event planning, and can therefore articulate a change in pace and dynamics with varying degrees of grey-scale.

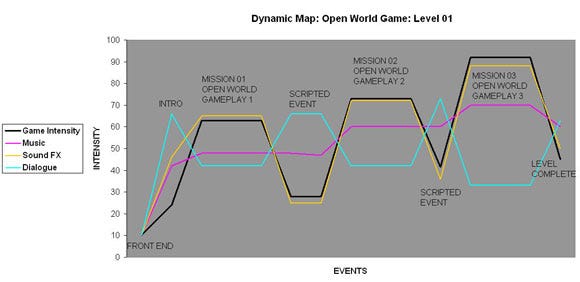

However, the less linear and more emergent a game-play experience is, the less control game designers have over the second to second dynamics of the game experience that the players will experience. Different player styles are often accommodated in open world game and it is arguably this player style that defines the emergent dynamics of the moment to moment game-play.

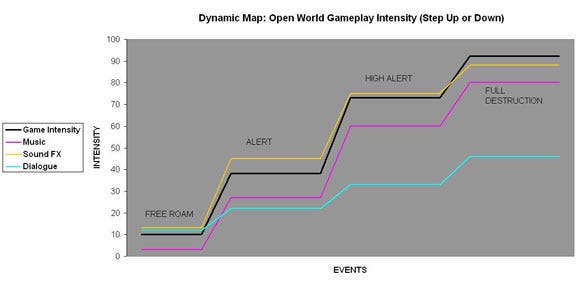

While it is hard to consider a dynamics map for an open world title, there will still need to be some high level story-wide map of the whole experience, and perhaps a couple of extra map types detailing the escalation and reduction of intensity in steps for open world combat and associated game-play mechanics (fig 2).

Fig.2 Escalation Dynamics map for an open world intensity.

The tighter the control over the player's movements and actions, the more scripted changes of mood and pace can be achieved, this arguably allows for a more cinematic experience. Below are two examples of two different types of game and the amount of resolution in dynamics terms that can be achieved in terms of events and the ability to change pace (figs 3 & 4)

Fig.3 Dynamics map for linear title (level)

Fig.4 Dynamics map for open world (level)

As can be seen in all the above examples, dialogue becomes more intense when the action is less intense. This is one of the core principles and gains for this kind of planning, allowing designers to know when that dialogue can only really be concentrated upon and understood in less intense game-play moments will dramatically change the way events are designed and implemented.

Much of the time dialogue is expected to be clearly audible within intense firefights, and it usually becomes a last minute mix problem to fix these issues. Yet with some simple planning these kind of sound problems can be avoided and the quality and coherence of the overall game experience can be hugely increased.

In the end, the plotting out of the game's dynamics is an essential tool for the audio personnel to be able to deliver what is necessary at each moment in the game. It enables understanding of not only what should be happening in that moment, but what has happened in the preceding moment, and what is about to happen next. This method can also help to identify areas where intensity design is weak and needs to change.

For audio to be able to affect design decisions in these matters is crucial in the development of cohesive game and audio design. It is the context of a game event or moment that makes it engaging and immersive for the player, not merely treating each moment as isolated and occurring in a vacuum. It so often occurs that audio feedback is given in terms of making events or sound effects bigger and more intense, with little or no consideration for the overall dynamics of the game.

The more these requests are implemented, the more the game starts to sound like it has no dynamic range, no subtle qualities to bring the player into the story or the game play and when it truly is the time to make something sound huge and impressive due to demands of the story, you'll find that there have already been dozens of events that already sound as loud and as big as the end climax of the game and there is nowhere to go.

Visual planning as shown in these dynamics maps is an essential tool to instantly communicate, with a variety of disciplines, the intended moments of chaos and the moments of calm in a video game design. It can also highlight areas in game design and flow that can be easily and quickly corrected before it is too late in the production process.

Read more about:

FeaturesYou May Also Like