In this illustrated analysis and historical retrospective, Super Meat Boy co-creator Edmund McMillen discusses approaches to difficulty in games, and explains how his game addressed the difficulty problem.

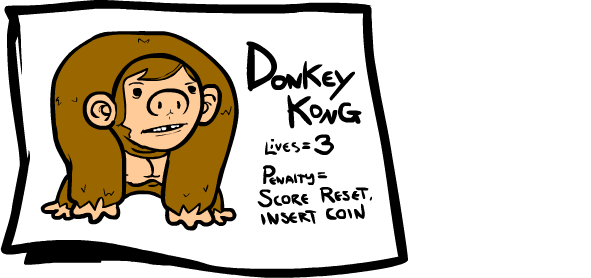

[In this analysis and historical retrospective, Super Meat Boy co-creator Edmund McMillen discusses approaches to difficulty in games, and explains how his game addressed the difficulty problem.] Difficulty in a platformer is usually established by a very simple formula: (Percent chance the player will die) X (Penalty for dying) = Difficulty It's pretty basic stuff: The higher the chance the player will die and the bigger price they pay for dying, the harder the game will appear to the player. This is a formula that's been around from the start, but the one thing that's changed drastically over the years is the "penalty" aspect. Penalty for dying in video games started in the arcades where the major penalty was adding a quarter.  This worked very well when it came to getting money from kids, but once home consoles became the norm the player no longer had the ability to add credits with coins and the formula had to change. The goal of achieving a high score was replaced with progression to completion, and the major penalty became going back to the start.

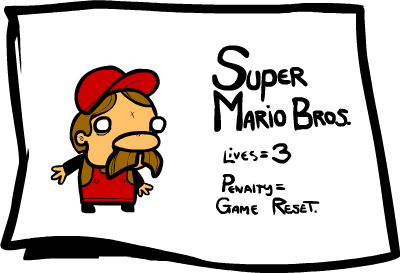

This worked very well when it came to getting money from kids, but once home consoles became the norm the player no longer had the ability to add credits with coins and the formula had to change. The goal of achieving a high score was replaced with progression to completion, and the major penalty became going back to the start.  This is also when the "risk/reward" balance was heavily established. Risk/reward was a way for the designer to give the player a way to gain more credits by taking bigger risks. In Super Mario Bros., the risk was collecting coins and exploring to find extra lives. The Mario formula was solid, but as video games tapped into a more mainstream market, penalty for losing had to become less frustrating, and penalty equals frustration. Companies wanted more people to be able to complete their games, and by the early 90s most platformers added a "continue" option.

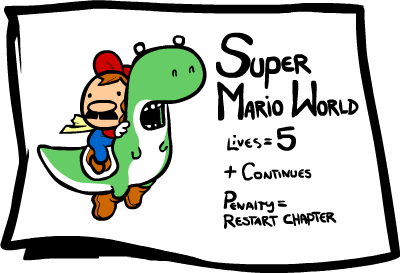

This is also when the "risk/reward" balance was heavily established. Risk/reward was a way for the designer to give the player a way to gain more credits by taking bigger risks. In Super Mario Bros., the risk was collecting coins and exploring to find extra lives. The Mario formula was solid, but as video games tapped into a more mainstream market, penalty for losing had to become less frustrating, and penalty equals frustration. Companies wanted more people to be able to complete their games, and by the early 90s most platformers added a "continue" option.  As time has passed, lives systems and penalties have almost vanished from most games due to the amount of frustration they caused, and difficulty has become watered down to the point of it no longer being a significant factor. By the mid-2000s, the independent video game scene started to use a more direct and simple formula.

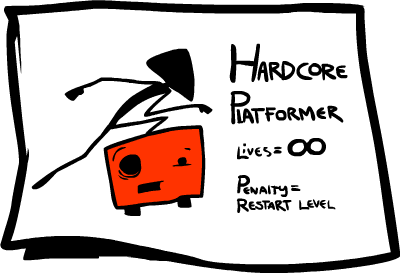

As time has passed, lives systems and penalties have almost vanished from most games due to the amount of frustration they caused, and difficulty has become watered down to the point of it no longer being a significant factor. By the mid-2000s, the independent video game scene started to use a more direct and simple formula.  Removing lives altogether lets the designer base difficulty more on the actual level design and challenge and less around the penalty of losing lives and restarting. In doing so, the formula for difficulty changes. The player no longer has to worry about dying, and the penalty for death basically turned into the amount of time you took to restart after death and the length of the current level. So how could we take this existing formula, refine it, and apply it to Super Meat Boy? How could we make a seemingly aggravatingly difficult game into something fun that the player could get lost in? When starting the development of Super Meat Boy, these were the big questions that needed answers right away, and this is what we came up with: 1. Keep the levels small

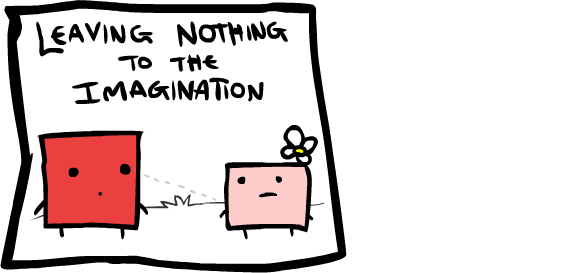

Removing lives altogether lets the designer base difficulty more on the actual level design and challenge and less around the penalty of losing lives and restarting. In doing so, the formula for difficulty changes. The player no longer has to worry about dying, and the penalty for death basically turned into the amount of time you took to restart after death and the length of the current level. So how could we take this existing formula, refine it, and apply it to Super Meat Boy? How could we make a seemingly aggravatingly difficult game into something fun that the player could get lost in? When starting the development of Super Meat Boy, these were the big questions that needed answers right away, and this is what we came up with: 1. Keep the levels small  It was very important that the levels in Super Meat Boy be bite-sized. You could think of most of them as "micro-levels," thrown at the player in rapid succession, much like the micro-games in the Wario Ware series. If we keep the levels small enough for the player to see his or her goal, it lowers the stress of not knowing what's coming and the distance necessary to re-traverse after death. 2. Keep the action constant

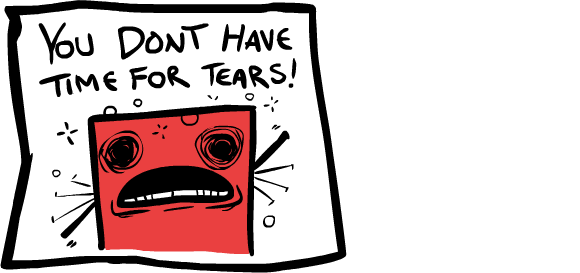

It was very important that the levels in Super Meat Boy be bite-sized. You could think of most of them as "micro-levels," thrown at the player in rapid succession, much like the micro-games in the Wario Ware series. If we keep the levels small enough for the player to see his or her goal, it lowers the stress of not knowing what's coming and the distance necessary to re-traverse after death. 2. Keep the action constant  It was imperative that the action never stop, even when the player was killed. The time it takes for Meat Boy to die and respawn is almost instantaneous. The player never waits to get back into the game, the pace never drops, and the player doesn't even have time to think about dying before being placed right back where he left off. This same idea was applied to the level progression. Players never leave the action until they want to, the levels keep coming as fast as the player can beat them, and all the complete screens, transitions, and cut-scenes are sped up to maintain the fast pace of the game. 3. Reward

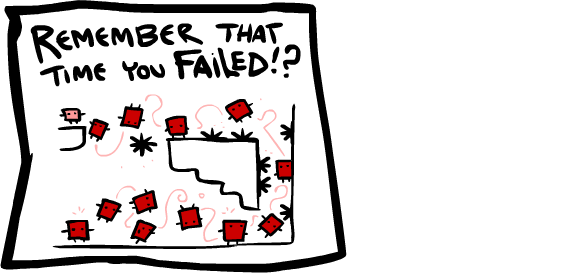

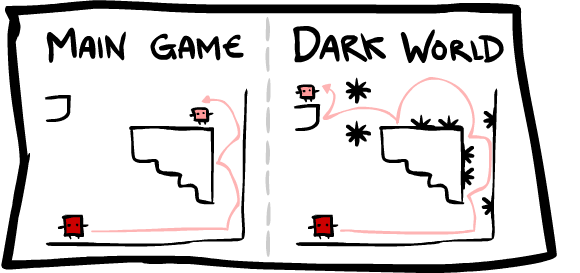

It was imperative that the action never stop, even when the player was killed. The time it takes for Meat Boy to die and respawn is almost instantaneous. The player never waits to get back into the game, the pace never drops, and the player doesn't even have time to think about dying before being placed right back where he left off. This same idea was applied to the level progression. Players never leave the action until they want to, the levels keep coming as fast as the player can beat them, and all the complete screens, transitions, and cut-scenes are sped up to maintain the fast pace of the game. 3. Reward  The player should always feel good about completing something hard, so what better reward then a reminder of just how hard that level was? Early in development, co-developer Tommy Refenes implemented the replay system, incorporating a mode that upon level completion would show the player's past 40-plus attempts all playing at once. This simple visual reward for taking a beating not only reminds the player of just how hard he tried, but also shows a timeline of how he learned and got better along the way. With our basic outline and a hardcore platformer geared towards our horribly spoiled ADD generation, how could we stay true to the extremely high difficulty par set by games like I Wanna Be The Guy, Jumper, and N+, yet still be accessible enough for someone who was new to the genre to pick up and enjoy? Was there a way to make something accessible and still hardcore? This is where the "dark world" system comes into play. The dark world is an expert mode set parallel to the main game. As the player completes levels they will unlock expert versions in the dark world if they complete the level under a set par.

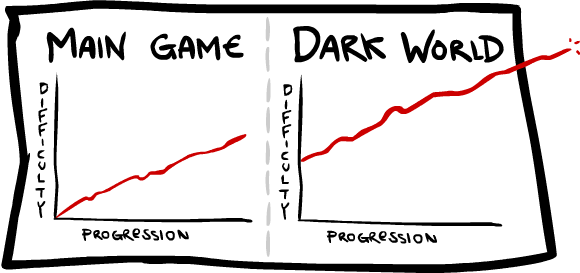

The player should always feel good about completing something hard, so what better reward then a reminder of just how hard that level was? Early in development, co-developer Tommy Refenes implemented the replay system, incorporating a mode that upon level completion would show the player's past 40-plus attempts all playing at once. This simple visual reward for taking a beating not only reminds the player of just how hard he tried, but also shows a timeline of how he learned and got better along the way. With our basic outline and a hardcore platformer geared towards our horribly spoiled ADD generation, how could we stay true to the extremely high difficulty par set by games like I Wanna Be The Guy, Jumper, and N+, yet still be accessible enough for someone who was new to the genre to pick up and enjoy? Was there a way to make something accessible and still hardcore? This is where the "dark world" system comes into play. The dark world is an expert mode set parallel to the main game. As the player completes levels they will unlock expert versions in the dark world if they complete the level under a set par.  The dark world's difficulty starts where the main game's difficulty leaves off. You could say level 1-5 in the dark world is almost as difficult as level 3-5 in main game.

The dark world's difficulty starts where the main game's difficulty leaves off. You could say level 1-5 in the dark world is almost as difficult as level 3-5 in main game.  The goal was to create a system that allowed expert players to start the game experiencing high difficulty right off the bat, yet not require those levels to be finished to complete the main game. The dark world system allows for Super Meat Boy to become two full games. There are more than 150 main game levels for the average gamer and more than 150 expert levels for the hardcore gamer, but they are set up in a way that an average gamer who completes the main game can easily transition into the difficulty of the dark world levels. For those players, the game will unfold even more. Video games are exercises in learning and growing. The designer acts as the teacher, giving the player problems that escalate in difficulty, hoping their course will help them learn as they go, get better, and feel good about what they achieve. When you are trying to teach someone something, you don't punish them when they make a mistake. You let them learn from it and give them positive reinforcement when they do well.

The goal was to create a system that allowed expert players to start the game experiencing high difficulty right off the bat, yet not require those levels to be finished to complete the main game. The dark world system allows for Super Meat Boy to become two full games. There are more than 150 main game levels for the average gamer and more than 150 expert levels for the hardcore gamer, but they are set up in a way that an average gamer who completes the main game can easily transition into the difficulty of the dark world levels. For those players, the game will unfold even more. Video games are exercises in learning and growing. The designer acts as the teacher, giving the player problems that escalate in difficulty, hoping their course will help them learn as they go, get better, and feel good about what they achieve. When you are trying to teach someone something, you don't punish them when they make a mistake. You let them learn from it and give them positive reinforcement when they do well.  [This analysis was originally posted on SuperMeatBoy.com, which has more information on Edmund's upcoming IGF-nominated XBLA, WiiWare and PC action platform title.]

[This analysis was originally posted on SuperMeatBoy.com, which has more information on Edmund's upcoming IGF-nominated XBLA, WiiWare and PC action platform title.]

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like