Opinion: Illuminating the shadowy group celebrating Valve's latest censorship drive

Gamasutra contributor Katherine Cross digs into the history and agenda of the National Center on Sexual Exploitation, a right-wing advocacy group gleefully campaigning for Valve to censor Steam games.

Amidst the controversy surrounding Steam’s latest volte face on “sexually explicit content,” one celebration has passed without much comment. An advocacy group calling itself the National Center on Sexual Exploitation (NCOSE) rejoiced at the news, breathlessly declaring “VICTORY!” Their press release was unstinting:

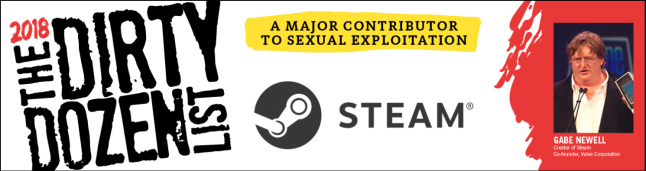

“This sudden action by Valve, parent company of Steam, comes after a two-year aggressive campaign by the National Center on Sexual Exploitation, including the listing of Steam on the 2018 Dirty Dozen List.”

The NCOSE was founded in 1962 as Morality in Media, a Christian interfaith “anti-obscentiy” organisation. The rebrand happened in 2015 and its overtly conservative Christianity was submerged beneath inoffensive rhetoric. They now describe their mission as one “to defend human dignity and to oppose sexual exploitation.”

Their bid for mainstream relevance finds further expression in their co-optation of feminist rhetoric. For instance: “We thank Steam for their leadership in working to change our #MeToo culture in which sexual violence in [sic] rampant and normalized.” They ran a campaign against Steam, encouraging emails and tweets directed at the company in a “a heightened week-long grassroots campaign, which began on May 10th,” adding them to their “Dirty Dozen” list of firms that, in NCOSE’s view, promote or disseminate pornography. Twitter is also on the list because sex workers have accounts on the platform.

Rhetoric aside, the organization is resolutely right wing. It’s a popular “expert source” on conservative blogs and news organizations who cover and amplify their campaigns; its president, Patrick Trueman, served in the first Bush Administration and he, like several of his fellow board members, is tied to the Catholic Church. Its twitter promotes other conservative, anti-porn crusaders, like one obscure New York-based group called NY Families which purports to offer “pro-life, pro-family, conservative Christian perspective on all things New York State.” NCOSE agrees with their stance that porn should be declared a “public health crisis” by the state. Recently, NCOSE has also tried to blame the serial rapes of the state’s former Attorney General, Eric Schneiderman, on BDSM. All this gives a sense of the particular ideological brew they’re peddling.

"There is something to be said for game studios and platform holders having a certain amount of political literacy when they come across groups like this who suddenly flood their inboxes with complaints."

But, as has always been the case, there are those few feminists--relics of the anti-porn drives of decades past, which most of us have moved on from--who are happy to ally with the extreme right. NCOSE has promoted the views of Gail Dines--a noted, loathsome anti-sex-work activist--and one Alabama Whitman, a transphobic, anti-sex work feminist whose website “misandristicbitchsquad.com” has been flagged for spreading malware, appropriately enough.

In that vein, the organization was also vocally supportive of the US Congress’ recently passed FOSTA-SESTA bill, a bipartisan act which criminalized a great deal of online sex advertising in the name of curbing “human trafficking.” In practice, the bill further marginalises and terrorises sex workers by further limiting their options to safely advertise their trade.

There’s been some speculation that the bill, which now holds platform-owners liable for any “trafficking” content (broadly defined), played a role in Valve’s decision to censor games it had previously approved--sometimes in direct consultation with their developers. That may be overstated, but given the flinchiness of other corporations just down the road, like Microsoft banning “nudity and pornography” from its Skype service, it’s not hard to see why some would assume such a connection.

In any event, this is the climate of censorship and fear that NCOSE and its fellow travellers seek to impose on women--and those who connect with the “wrong kind” of woman, or who enjoy art that depicts us in a way these organizations disapprove of. NCOSE is typical of the organizations that are pushing for genuine censorship of videogames: politically conservative, well-funded, and tied to powerful institutions like governments or corporate lobbies. In the case of NCOSE, besides its well-connected board members, it also enjoyed grants from the second Bush Administration’s Department of Justice to create an online database of citizen generated “obscenity complaints.” They aggregated over 67,000 such complaints and forwarded them to the DOJ; none led to a criminal prosecution.

The organization thus has an ambitious agenda--ridding the world of porn and sex work (and sex workers, frankly)--but its history is a bit Keystone Cops. One should therefore take their grandiose proclamations with a grain of salt. It’s unsurprising that they, like any advocacy group, would try to claim credit when an issue goes their way. But there is something to be said for game studios and platform holders having a certain amount of political literacy when they come across groups like this who suddenly flood their inboxes with complaints.

NCOSE has deftly--and sickeningly--appropriated the #MeToo moment to push a right wing agenda that harms women, trying to cloak themselves in the mainstream credibility gained by the blood, sweat, and tears of actual survivors. There’s a breathtaking cowardice to that act of theft; the organization appears to realize that its brand of religious conservatism lacks a broad base of support, thus they have to filch someone else’s. In the process, they ironically undermine the credibility of MeToo itself by tying its name to trivial matters, as some responses to their tweets indicate.

Gaming studios and distributors have a responsibility to stop this sort of thing dead in its tracks, as it only propagates through successful campaigns like the one against Valve. Even if NCOSE played no real role in the decision, it’s a feather in their cap all the same; it validates their worldview and encourages their ideological fellow-travellers to push harder. In this specific case, it also contributes to the debauching of a genuinely important movement against sexual abuse.

***

NCOSE rallied against an easy target, an abysmal and borderline unplayable game (pictured) called House Party that, at points, can simulate date rape.

Here’s one pre-written tweet that NCOSE encouraged its followers to share:

“@steam_games please remove the game House Party - black bars over the nudity are not enough - this game is all about coercing or tricking women into sex. #parentingtips #onlinesafety #videogames”

It was not widely tweeted, in the end. But this strategy--using a reprehensible, soft target as the justification for considerably more expansive action--is a common one with these sorts of organisations. House Party had already been the subject of controversy last year, when it was removed for “pornographic content” and then re-admitted it once it censored its subjects.

NCOSE also didn’t get everything it claimed to want. Its call to action demanded Valve do the following:

1) Remove the game House Party due to its singularly degrading and exploitive themes.

2) Create an 18+ category on its website where all games with any amount of nudity or sexual content are stored. All accounts should have this 18+ category disabled by default, and require an extensive opt-in to view it so that children are no longer automatically exposed to this content.

3) Institute a more robust policy enforcement against selling games that normalize or glamorize sexual exploitation in the future, no matter the age of the user.

As far as I can tell, point 1 isn’t in the offing (House Party’s devs have been silent on the matter), and point 2 certainly hasn’t been addressed. But it’s the third point that constitutes what NCOSE really wants. House Party was the fig leaf, Point 2 was the inoculation against appearing censorious, Point 3 is the ultimate goal. Given their broad definition of “glamorizing sexual exploitation,” and their happiness with Valve’s latest crackdown, it’s safe to surmise that NCOSE would be plenty happy if no sexual games whatsoever were permitted on Steam.

While all creativity is stifled by a blanket ban on games with sexual content (one which will, inevitably, be applied inconsistently and harm smaller creators as opposed to, say, BioWare or CD PROJEKT RED) we know from history that NCOSE’s brand of “decency” crusading harms women and queer people the most, with our art often being used as the Ur example of the “indecent” or “degenerate.” No one should be surprised that a relatively tame game about lesbians (Kindred Spirits on the Roof) got swept up in a moral panic about “sexually explicit content.”

Corporations looking to appear “woke,” but lacking in political literacy, may be fooled by groups like NCOSE with bland names and generic mission statements. Who, after all, would oppose human dignity? But what these groups actually want has nothing to do with the dignity of anyone, and everything to do with restoring a traditional gender order that criminalizes both sexual expression and sexual labor. No branch of the tech industry should want any part of it.

Whatever role NCOSE played in Valve’s decision, there’s value in knowing about their tactics and the cowardice with which they’re employed. It can only lead to more open and honest discussions about sexuality in gaming.

Katherine Cross is a Ph.D student in sociology who researches anti-social behavior online, and a gaming critic whose work has appeared in numerous publications.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like