Book Excerpt - 21st Century Game Design: Designing for the Market

In this excerpt from 21st Century Game Design, the authors suggest how to make game design relevant to the business side of the game development process, because the commercial success of a medium clears the way for artistic expression.

The following is a selected excerpt of Chapter 2 from 21st Century Game Design (ISBN 1-58450-429-3) published by Charles River Media.

--

Why is game design often overlooked as an important factor contributing to game sales? Perhaps because when most people in development companies talk about “good game design,” they mean “game design that produced a game I really like.” This sort of subjective validation of game design is of no use in business, which thrives on repeatable methods based around capturing a target audience—the market. Unable to see the profit resulting from “good design”— especially since many allegedly well-designed games fail commercially— most businessmen ignore design entirely.

Design is not suggested to be the only (or even the primary) factor in the sales of a game. Marketing, for example, is hugely important in making a product visible in a crowded market. Similarly, the sales of a game depend greatly upon the budget for development. A game developed on a budget of $100,000 should not be expected to achieve sales figures equivalent to a game developed on a budget of $5,000,000. However, mechanisms such as word of mouth transmit individual opinions of a product, opinions that will be swayed by the design content of the game.

Therefore, we face a great need to make game design relevant to the business side of the game development process. Once the ragtag market has stabilized, we will have plenty of time to pursue the artistic side of game development, but for the time being, that is a luxury we cannot afford. We would not see inventive filmmakers like the Coen Brothers were it not for commercially motivated film makers like Spielberg and Bruckheimer, because the commercial success of a medium clears the way for artistic expression, not the other way around.

Demographic Game Design

A first step is to consider a criteria for success—what is a successful design? Notions such as elegance, a criteria famously applied to the design process by Ernest Adams, are great aspirational concepts, but less useful for business purposes. Systemic production rules, such as Noah Falstein's “400 Project,” provide neither a success criteria nor aspiration and are useful mainly as a means of provoking discussion.

The concept of demographic game design is that game design inherently targets an audience, and therefore the success criterion for a design is how effectively it satisfies the needs of that audience. This factor is not directly related to sales figures and is not intended as a means by which to consider the success of the game as a whole—only the success of the design. If the target audience is satisfied by the game (which can be determined by appropriate sampling techniques), the design can be considered a success.

However, before these criteria can be applied we must know the demographics that are available to be targeted, so the first step in demographic game design is to study the audience. If the game designer is to act as a player advocate in the development process—as if they are an elected politician reflecting the diverse needs of their constituency—they must first acquire a useful audience model.

A Warning on Statistics

It has often been said that you can make statistics prove anything you want, and this is true—provided the people you are talking to lack the critical faculty to see the flaws in the presented argument. Nonetheless, statistical principles are a vital part of modern business and science. Quantum mechanics, which all modern computing depends upon, is essentially statistical in nature, and even the concept of “species” is not a Platonic ideal, but a Gaussian distribution of diverse life forms arranged into clusters, which we choose to term “species” only by convention.

The most important thing to remember when dealing with statistics of any kind is that showing a correlation (a connection between two events, details, or tendencies) does not prove causality; it is merely a clue to something interesting. For example, in one famous incident a statistician found a statistically significant correlation between babies and storks in Switzerland. Storks were consistently nesting on houses with newborn children. This fact did not prove that babies were brought by storks, of course, and on investigation it was discovered that the houses with newborn babies were kept warmer than other houses. This extra warmth attracted the storks. The lesson is that statistical correlations tell you nothing of the underlying causal mechanisms.

The other important aspect of statistics is that statistical data about a group tells you nothing about individuals in that group. For example, it is well known that the majority of college students drink alcohol, but this statistic does not allow you to know whether any given college student drinks alcohol. Reasoning about the general tells you nothing about the specific. The advantage of statistics is that whatever does not average itself out to insignificance in a given set of data is a tendency that can be counted on. For example, statistical analysis has demonstrated to the movie industry that roughly 50% of the audience of a profitable film return to see a sequel, allowing for strategies involving producing cut-price sequels for short-term gain.

Market Clusters And Audience Models

The notion of a market cluster (or market segment) originates in marketing. In recent years, with the advent of narrowcasting channels such as specialist TV stations and personal e-mail, cluster analysis has fallen out of favor in marketing, but the technique still has value in other disciplines. The basic principle is to analyze a data set containing information on a particular group of people and look for common traits that when taken together define a coherent group or cluster.

For example, the vacation travel market identified three distinct clusters: the demanders, whose priorities are exceptional service; the escapists, who want to get away and relax; and the educationalists, who want to see new things, experience new cultures, and so forth. These categories emerged from a cluster analysis on data taken from a pool of vacation makers; this data was then sorted by a clustering procedure. Note that the categories were named after the cluster analysis—the names were created to capture the feel of an abstract cluster of people who shared some common traits.

This cluster analysis approach is one of the more formal ways of producing an audience model, but a simpler method exists that anyone can apply: observation and hypothesis. In essence, you observe many different people from the audience (or look at statistical data in general) and draw a hypothesis from the observation. In science, this would be followed with an attempt to validate the hypothesis. Alas, in the games industry, many hypotheses are treated as a priori facts. However, provided you remember that such a hypothesis is only a working assumption and needs to be tested to determine its value, we find nothing wrong with building an audience model in this way.

Hardcore and Casual Split

This is the most basic audience model at use in the games industry today. It is in essence a consensual hypothesis—that is, a hypothesis which the majority accept as factual—and almost all people working in the games industry know what is meant by the Hardcore (or Core) market and the Casual market. Some data at use in the industry might confirm this split, but since no formal definition for each group exists, it remains in essence a hypothetical model.

The essence of Hardcore players can be summarized as follows:

Buy and play a lot of games

Game literate (that is, familiar with the conventions of current games)

Play games as a lifestyle preference or priority

Turned on by challenge

Can be polarized—that is, a large proportion can be made to buy the same title

Capcom characterized the Hardcore approach at the start of Resident Evil on the GameCube (Capcom, 2002) as “Mountain climbing.” This ego-neutral characterization was used at the start of the game to determine which players were Hardcore in their approach and therefore required greater challenge. Selecting this option ran the game at a higher difficulty level.

On the other hand, Casual players can be summarized as follows:

Play few games—but might play them a lot

Little knowledge about game conventions

Play to relax, or to kill time (much as most people view TV or movies)

Looking for fun or an experience Inherently disparate—cannot easily be polarized

Capcom characterized the Casual approach in the GameCube Resident Evil as “Hiking.” Players who selected this option played the game at an easier setting, allowing them to have more fun and enjoy the experience without the greater emphasis on challenge (which often equates to greater emphasis on repeated failure). The full wording of the sorting question at the start of this game is as follows:

Question: Which best describes your opinion about games?

I. MOUNTAIN CLIMBING—Beyond the hardships lies accomplishment.

II. HIKING—The destination can be reached rather comfortably.

The value of this somewhat unusual question over a straight choice between “Easy” and “Normal ” (or “Easy” and “Difficult”; or “Normal ” and “Difficult”) is psychological. A Hardcore player faced with “Easy” versus “Normal” will pick “Normal,” but a Casual player is equally likely to pick “Normal,” thinking that choosing “Easy” makes them deficient in some way. The choice between “Normal” and “Difficult” is likely to cause some Hardcore players to select “Normal” (on the grounds that “Difficult” settings are for replay value) and then complain that the game is too easy. Finally, a choice between “Easy” and “Difficult” is likely to mislead both Casual and Hardcore types as they try to decide which of these two options is the normal setting.

In principle, the advantages of this approach are that tailoring the gameplay to the audience—and sorting the audience correctly—improves the reception of the game, equating to stronger sales. Unfortunately for Resident Evil on the GameCube, the slow-burning sales of the platform somewhat interfered with the actual unit sales. However, informal observation shows that Hardcore players were satisfied with the degree of challenge they received in “Mountain climbing” mode, while Casual players had no difficulty completing the game in “Hiking” mode.

This example clearly shows the value that even a simple audience model can have when used to approach the design process. The sorting question was a novel approach, and although it provoked some confusion in game-literate reviewers, the basic approach seems sound and could be refined to a more subtle approach.

Genre Models

Another hypothetical model in common use throughout the games industry is the genre model. In this, we assume that the audience primarily buys games of a particular type, and those types are referred to as “genres,” much as films and books are divided into genres according to their tone and content.

For example, the popular (Hardcore) Web site GameFAQs divides games into the following genres:

Action

Adventure

Driving

Puzzle

Role-playing

Simulation

Sports

Strategy

These genres are often divided into sub-genres, which further define the content of the game.

On the surface, this approach seems valid—you can certainly quickly acquire data on the relative sales of games of the given genres and thus make market decisions based upon these categories (or another set of categories).

However, an essential problem exists. As mentioned before, the Hardcore is game literate, but the Casual market is not. In this sense, the Hardcore can connect a game with its genre type, but the Casual market does not buy on the basis of genre at all, looking instead for a game that appeals to them on other terms.

A parallel with the film industry exists. Films are also divided into genres, but the majority of the audience base their film-going decisions not on the basis of genre, but on the basis of which stars are in the film. The “pulling power” of an actor or actress mostly drowns out the effectiveness of genre. For example, romantic comedies are relatively popular (based on total box office receipts), but a romantic comedy without a recognizable star or enough advertising money being spent is generally doomed to obscurity.

Also, you have the issue that genre categories are extremely vague. “Action” would seem on the surface to include both first-person shooter (FPS) and platform games, for example, despite the fact that both types of games attract an entirely different audience. You could use more precise genre categories, but the more precise the genre category, the more subjective the definition becomes. This is because genre definitions are inherently subjective in nature—you cannot objectively measure the gameplay content without specifically defined tests, and any genre system built from specifically defined tests will inevitably disagree to some extent with the mental conception of these genre categories in almost all people who encounter them.

The biggest danger with using the genre model is to assume that if a game from one genre attracts an audience of a certain size, and a game from another genre attracts an audience of a certain size, then a game that combines these features will have a much larger audience. This is the set intersection error: if 70% of people like apple pie and 50% like cherry pie, the likelihood of someone wanting to eat cherry and apple pie is likely to be around 35% (the intersection value of the two separate sets), that is, much lower. So in an audience of 100 people, where 70 like apple pie and 50 like cherry pie, an apple and cherry pie is more likely to appeal to about 35 people (the intersection), not 120 people (the sum). Although expressed in these terms it might seem obvious, it is a surprisingly common mistake throughout the game industry.

This doesn't mean that a game can't mix elements between genres (apple and cherry might turn out to be very complementary flavors!); only that combining the core gameplay of two disparate games is a dangerous endeavor. Mace Griffin: Bounty Hunter (Warthog, 2003) tried to combine the first-person shooter genre with the space shooter genre; Haven: Call of the King (Traveller's Tales, 2002) combined multiple genre types (including platform, driving, space shooter, and even rhythm action). Both games performed poorly in commercial terms, despite relatively high production values.

We face, however, a danger inherent in ignoring the genre model completely. The game literate Hardcore (who buy more games than the more numerous Casual players) often buy a majority of titles in a genre they have become personally committed to. If a game defies genre boundaries, it might struggle to polarize the Hardcore, and therefore suffer in terms of sales. If, however, it defies genre boundaries and goes on to succeed, it will nucleate a new sub-genre in the minds of the Hardcore audience, which is market gold dust. The original Resident Evil (Capcom, 1996) and the Tony Hawk's Pro Skater series (Activision, 1999 onwards) both benefited from this effect, founding the pseudo-genre of survival-horror (a term which Capcom created themselves for that game) and the sub-genre of extreme sports, respectively, and going on to exert brand dominance in these new market segments.

Electronic Arts' Audience Model

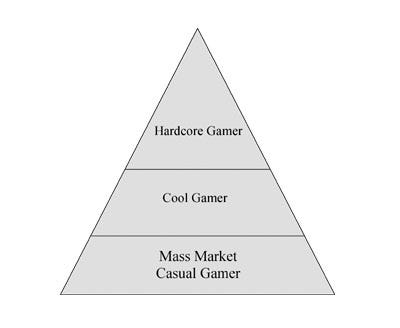

The world's largest game publisher (at the time of writing), Electronic Arts (EA), has publicly discussed at least one of their audience models, based upon their own internal data and research. This can be considered a theoretical model—that is, it has been devised to explain specific trends in data and is not a pure hypothesis. It can be seen in Figure 2.1 and has evidently evolved from the Hardcore-Casual split hypothesis.

Figure 2.1 alludes not only to the market segments, but also to the relative size of these clusters: the Hardcore gamer cluster is seen as the smallest, and the Mass Market Casual gamer cluster is the largest. Additionally, Figure 2.1 alludes to the way in which game sales are propagated through the market (the dominant market vector), that is, Hardcore gamers influence the Cool gamers to buy games, and the Cool gamers influence the Casual gamers to buy games.

|

|

|

| ||

| Figure 2.1. An audience model used by EA. This diagram is based upon material discussed by Richard Leinfellner at GPDC in Liverpool, October 2003. |

The three clusters are characterized as follows:

Hardcore Gamers: This cluster reads the specialist press (magazines about games), plays demos, rents games before buying (especially in the U.S. market) and can play as many as twenty-five games (or more) each year.

Cool Gamers: A typical Cool gamer has a Hardcore friend who is their primary source of advice about buying games. They are part of big peer group, are swayed in their buying decisions by the opinions of this play group, and tend to play the current top ten hits in the gaming charts.

Mass Market Casual Gamers: The least game literate cluster in this model consists of a huge market of people who are in general swayed in their opinions of games by Cool gamer recommendation and TV advertising. They play predominantly the current top three hits in the gaming charts.

This model clarifies several key points. First, ignoring the needs of the Hardcore market to reach the larger mass market is a risky prospect, since the Hardcore gamers are the initial point from which awareness of a game in the market as a whole originates. Second, a large enough advertising budget to reach the Mass Market Casual gamers is justified only on a game that is capable of being enjoyed by this group. Spending a lot of money on marketing a game that can appeal only to the Hardcore is to commit a strategic business error.

The disadvantage of this model from the point of view of design is that it says very little about the design needs of these clusters. Knowing that the Cool gamer demographic is influenced by the Hardcore tells us very little about what design elements are needed to appeal to this group. However, it is a stepping point from which we can proceed to investigate the pertinent design aspects. This is understandable, since design issues were not the primary reason for the construction of the model, which is intended as a tool for understanding the market dynamics.

ihobo Audience Model (2000–2003)

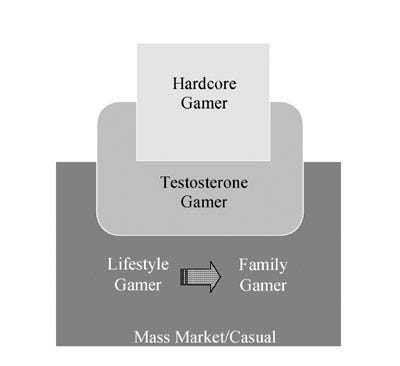

Up until the end of 2003, the audience model used internally at International Hobo Ltd. (referred to as the “ihobo audience model”) is the one presented in Figure 2.2. Like the EA model, this ziggurat-style depiction shows both the influence and size of the cluster. The model evolved out of market research and case studies and, like the EA model, is theoretical and not hypothetical in nature.

|

|

|

| ||

| FIGURE 2.2 The audience model used by International Hobo from 2000–2003. |

The two square groups—Hardcore gamer and Mass Market/Casual—are related in the same means of influence as two adjacent layers in the EA pyramid model.

That is, the Hardcore gamer is the primary source of influence for the Lifestyle and Family gamer (which are divisions of the Mass Market/Casual audience). In addition to the vertical influence, a horizontal influence exists in the Mass Market/Casual layer—the Lifestyle gamers can influence the Family gamers. The Testosterone market segment is a special case that straddles the Hardcore/Casual divide, but is highly pronounced and therefore worthy of attention.

The clusters are characterized as follows:

Hardcore Gamer: As mentioned in the Hardcore-Casual split model, Hardcore gamers' primary concern is challenge, and they are in general looking for games to provide a satisfying level of difficulty. No control mechanism is too complex for a Hardcore gamer, provided they like the core game activity. They are the principle game evangelists and serve a vital role in the market because of this.

Testosterone Gamer: This group is predominantly male and consists of people with both Hardcore and Casual tendencies. The defining trait of this groupis a content fixation: these players are most interested in games that focus around cars and guns, and also in games built around player versus player competition (such as the fighting genre). Complex control mechanisms can be tolerated, but not to the same degree as the Hardcore. They have the potential to influence the Lifestyle and Family gamer clusters in the rare cases that their tastes in games correspond to the tastes of the Casual clusters.

Lifestyle Gamer: These are broadly equivalent to EA's Cool gamer but are characterized here by their game design needs. Lifestyle gamers want fun, enjoyable activities in their game, and they don't in general want to be prevented from progressing through the games they play. Easy to grasp control mechanisms are essential. They are also interested in good stories, a trait not dominant in the previous two clusters. Like the Cool gamer cluster, Lifestyle gamers need a game that feels socially acceptable to play—they will (as a generalization) not play anything that could embarrass them in the eyes of their peer group.

Family Gamer: The large but disparate Family gamer represents parents buying games for their children, which they might play with them or might play the same games alone in their spare time. They are primarily looking for entertainment, and control mechanisms must be exceptionally simple. Like the Lifestyle gamer, they enjoy a good story, but this is unlikely to motivate their purchasing decision. They are not in general interested in anything shocking or outlandish and prefer the familiar to the esoteric. They almost never buy games for themselves, and most games they play have either been purchased by a relative (usually an older son or daughter) or were bought for their children.

Note that that we have included no child clusters in this model. This is because the market segments were defined by purchasing habits, and since children generally have their games purchased by parents, the Family gamer demographic incorporates the child clusters in an indirect fashion. However, the children might fit the Hardcore, Testosterone, or Lifestyle demographic type, and therefore, the Family type characterizes not the children themselves but the extreme fringe of gaming—in essence, people who are encountering games only because of their children.

The application of this audience model uncovered a number of different design issues extremely pertinent to market economics, all of which are discussed later in the section “Design Tools for Market Penetration.”

_____________________________________________________

Read more about:

FeaturesAbout the Author(s)

You May Also Like