Featured Blog | This community-written post highlights the best of what the game industry has to offer. Read more like it on the Game Developer Blogs.

What I talk about when I talk about Narrative Design

Why do we tell stories? And what does it mean when we make them interactive?

It wasn’t long ago that I attended a lecture about narrative design. And as with many lectures I attended in the past, it focused solely on the spectrum between Aristotle’s ‘three act’ tragedy and Joseph Campbell’s ‘hero’s journey’.

Now, Aristotle never actually said every story should have three acts, and Campbell only analyzed myths and wrote “a book about similarities.” But that is beside the point. As a game writer, I can tell you that if you want to write a good story, be it for a video game or another medium, starting with these well-known structures is not the ingredient for success.

Rather than talk about the structures of tragedy and heroism, I would like to focus on the foundation first: why do we tell stories, and what does it mean when we make them interactive?

Love and Adventure

Take a short story like What Do We Talk About When We Talk About Love (1981), by Raymond Carver. Reading it will only cost you 20 minutes, tops, and it’s a terrific example of a story making good use of its medium. The plot: two couples sit together and talk about love. The main character, one of the husbands, whose perspective we follow, makes detailed observations about how everyone in the room interacts with one another. In between the anecdotes about former lovers, we see subtle clues implying the nature of their relationships. As someone who’s in a relationship, this story struck a chord with me, as I could see many of my thoughts and observations reflected in the writing. It was an interesting read that provided me with food for thought about the existence of ‘true’ love.

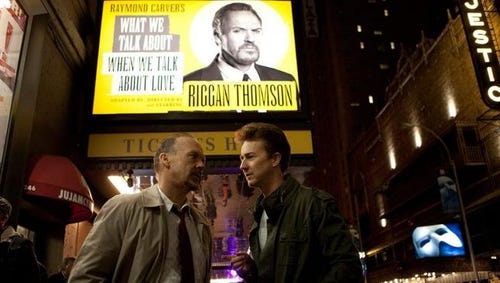

To me, Carver’s short story (also referenced heavily in the movie Birdman (2015)) doesn’t impose any moral compass as to what true love is, but rather, attempts to discuss and explore different views about the subject.

Let’s compare this to The Seven Voyages of Sinbad the Sailor, a more classic story set somewhere in the 8th century, Baghdad. The plot: a porter by the name of Sinbad sits beside a mansion one day and complains to God about the injustice of the poor having to work so hard while the rich do so little. A servant of the mansion overhears him, and decides to introduce him to the owner of the estate: Sinbad the Sailor. For most of the story, Sinbad the Sailor tells his poorer namesake about all his exciting, yet dangerous voyages. He argues that the porter’s stance on wealth and poverty is misplaced, for the pain that the porter endures in his everyday work is nothing compared to the supernatural challenges Sinbad the Sailor had to face during his adventures abroad. The wealth he managed to amass is honest compensation for all his hard work. The porter agrees with this sentiment, apologizes to his richer namesake and ends the story by stating that he feels he’s made a new friend.

The Voyages of Sinbad are obviously a very different type of story compared to the first example. It focuses on splendor and adventure, and carries a clear moral sentiment: people with a lot of wealth worked inhumanly hard to achieve it. A sentiment I personally don’t agree with in the slightest. But for a hard working porter in 17th century Baghdad (around the time when the story was said to have been written) the moral might be the key for making him content with his poor, but safe, life; causing him to pass on the tale to his children.

Truth and Revelation

We humans are inherently curious animals, and stories are interesting because they provide us with a method of learning. For me, a book about love is interesting because I unconsciously yearn for a way to find a frame of reference for my situation. Yet, for others, a story about magical adventures and the importance of a stable job provides both a temporary distraction and an extra motivation for working hard.

We follow stories in pursuit of a truth. And authors are there to provide answers. In a way, storytelling is a form of communication. And as with any form of communication, its interpretation is subjective too. A writer’s vision can easily be misinterpreted by the audience. Or maybe what the author thinks of their work isn’t even relevant.

When wanting to tell a story, or just a brief scene, ask yourself what it is you want to express, or what you want to talk about. To what ‘revelation’ does your story or scene lead? Say what you want about Fifty Shades of Grey’s (2011) ‘lack of literary quality’, but for many, this was the book which led them to exploring the possibility of BDSM - a story doesn’t have to be well structured for it to still be interesting to a large audience of people. That’s not to say I would forgo structure, but do start off with looking towards yourself and what you, as an author, want to express to the audience - what revelation you want them to lead to.

A good exercise to test this method is to start by writing a short story about a moment within your own life, and telling it in front of an audience. You will notice that by doing so, your ability to provide structure comes naturally - but knowing what exactly your story expresses, what to focus on and how to enhance that effect - that’s where the challenge lies.

So, how does storytelling then work in video games? How does making a player part of a story factor into the equation? Let’s talk about narrative design.

Narrative Design 101

Narrative Design, for me, is defined as the process of creating context and purpose around a game’s mechanics. Something from which all visual and audio assets can be derived. This often leads to creation of a premise, and eventually a story. Though sometimes, a title alone is enough. Case in point: Tennis for Two (1958) and Space Invaders (1978). Evidently, it doesn’t require a ‘narrative designer’ for it to happen during a game’s design process. But for many developers opting to engage their audience on a deeper level, whether it’d be a racing game or choice-driven RPG, having a dedicated narrative designer on board is a must.

Embedded Narrative

What sets narrative design apart from many other forms of storytelling is its addition of the player being part of the story the author wants to tell. It creates two forms of narrative: embedded and emergent. In Wolfenstein 3D (1992), the embedded narrative is quite simple: An agent is on his way to kill Hitler, along the way he kills a lot of Nazis. It’s more of a premise, really. The emergent narrative, the story which is created by the player, isn’t all that different: I went through a series of corridors, killed a lot of Nazis, and then killed Hitler.

The embedded narrative in Wolfenstein 3D exists to simply provide the player with a reason to shoot, and one that is morally justified within our society. A lot of games do this; it works surprisingly well, and provides a solid foundation. Now, Wolfenstein: The New Order (2014), released decades later, uses that same foundation and builds on top of it by making it a story about revenge.

The player/viewer’s pursuit for truth, for finding out how the story ends, is used as a reward mechanic, on top of it being there to simply provide context and reasons for the actions. For me, the story of Wolfenstein: The New Order was interesting because of how they portrayed the main character, William Blazkowicz. During cutscenes, Blazkowicz explains through monologue his thoughts and feelings about the current situation. Given the extreme nature of many of the game’s scenarios, which I will hopefully never experience, learning about Blazkowicz take on matters was compelling me to feel more invested in his story. It’s a foundation dramatic storytelling rests upon: we take a character with realistic and grounded emotions, and let them experience the most horrific and extreme situations (e.g. facing thousands of Nazis). Finding out what this does them piques our interest. Given that you are also inhabiting Blazkowicz during gameplay, I feel even more compelled to find out what happens to him.

But simply slapping on a revenge plot isn’t a recipe for success. The story of Tom Clancy’s Rainbow Six: Vegas (2006) follows an elite counter-terrorist unit attempting to track down a terrorist leader – yet, during most of the game, the attention is focused on killing waves and waves of terrorists. The cutscenes portray a grounded, realistic story in a modern setting. If one reads a Tom Clancy novel of watch a good movie adaption, one will see how most of the plot contains similar elements, minus the hordes of terrorists being killed. Tom Clancy novels are about the drama of avoiding conflicts, and the Rainbow Six team is nothing but a last resort for when stuff hits the fan. The first Rainbow Six games, released in the 90s, were all about planning and tactics, there was barely any plot. The stakes were high and the bullets very deadly, and that was enough to engage players.

Premise meets Gameplay

The plots for Rainbow Six: Vegas and Wolfenstein: The New Order both aim at motivating players by providing a story of revenge. For me, Wolfenstein succeeds by providing an over-the-top plot and setting which aligns well with its over-the-top gunplay; and then making me curious how normal people would react to these situations. Most of its cutscenes center around Agent Blazkowicz’ human and grounded perspective on matters. It’s a refreshing take, considering many FPS protagonists are usually a dull and characterless host for the player. Rainbow Six: Vegas’ story is all about tracking down the terrorist leader, someone who I barely see and have little emotional connection too. And the only part I get to play is killing the unrealistically high amount of terrorists in this casino, whilst a woman in a helicopter explains the actual plot to me. It’s attempting to tell a Tom Clancy story, but doesn’t understand what motivates people to read those stories. A better implementation would be to look at SWAT 4: a game with a similar premise, but instead of having a big revenge ark, every level has its own realistic and self-contained storyline, in line with what actual SWAT teams could experience.

A game’s embedded narrative must work hand-in-hand with the gameplay to offer a meaningful contribution. The viewer/reader’s pursuit for truth (as discussed earlier in the article) must align with the motivations a player would feel. And that brings us to the other side of the spectrum: emergent narrative.

Emergent Narrative

Upon release, Shadow of the Colossus (2005) was praised for its visual fidelity and engaging boss fights against massive creatures. But the final battle takes on a surprising twist: the player takes on the form of a Colossus themselves – whilst the player initially feels powerful in this role, they are unable to match the speed and dexterity of the human assailants who quickly manage to evade the now giant player and defeat him by using the player’s old magic sword. Given how, up until now, all the player did was use his sword and tiny size to outpace colossi and kill them, this should come as no surprise. Without dialogue or cutscene, the player experiences an unconventional form of situational irony.

Instead of using cutscenes, dialogue and other assets to convey the story to the player – the player experience, the ‘emergent narrative’, can be treated as a tool for storytelling itself. Just to make things clear: embedded narrative the term I use to describe a story being directly told directly to the player. The emergent narrative is the story players ‘experience’ as a result from the game’s dynamics. Cutscenes in Grand Theft Auto V (2013) are embedded (and scripted), while car chases are often emergent (and non-scripted). Both contribute to the story the player experiences.

Designers indirectly control the emergent narrative players experience. And in doing so, can create a story for players, too. Shadow of The Colossus is a great example: what the player does during the aforementioned reverse-boss encounter is up to them. This means that when the player acts to the designers wishes, by being a blunt tool of destruction, the story is experienced to its best degree. But I’ve also seen players getting confused by the change of camera perspective - leading to a somewhat less impactful result. But you can take it a step further, by having players actions directly affect the story they’re being told.

Choice and Reflection

Papers, Please (2013) has you step into the shoes of a border crossing immigration officer in a fictional eastern European country. The mechanics are anything but comfortable: every day, you’re given extra, convoluted, rules by which you determine who you’re allowed to let in or not. If the player breaks any particular rules they risk losing the game by getting arrested. If they don’t perform well enough, they also risk running their family in debt or having them die from famine and sickness.

Then, to add to this grueling experience, players are often approached by people asking to be let in for various moral reasons. But if the player really wants to survive, it is best to ignore all of these requests and focus on the job at hand. (That, or illegally collect passports for you and your family and plan your escape.)

By allowing, yet discouraging, player choice, the mechanics allow players to express their own values. While Paper’s Please is anything but fun to play, it does make for a truly memorable roleplay experience.

To provide a different type of example: Herald: An Interactive Period Drama (2017), a title I worked on, is a choice-driven adventure game. You play as Devan, a steward of mixed heritage, working on board a 19th century trading vessel. It’s a perilous journey, and players are quickly confronted with various dilemmas during which they must choose who to side with: the officers or the passengers? The easterners of the westerners? The rich or the poor? Our (design) goal is not for players to be some director – deciding on whether they want their character to be a bad-ass renegade or a paragon of virtue. With Herald we wanted to ask players what someone’s cultural and racial background determine about a person. It is through the interactive dialogue players decide who to align with, and, in doing so, determine their own opinion on which parts of Devan’s background matter the most to them.

Reading or experiencing stories can help us uncover truths. But being a part of that story, and making choices allow players to express themselves, learning something about their own values in the process.

I’m not saying I didn’t enjoy Fable (2004) with its rather simplistic moral scale. And of course I love to see it when my choices change the story like in The Witcher 2 (2011). But when prompted, player choices should be meaningful to the player, first. Consequences come later.

Conclusion

Storytelling is a form of communication that plays with everyone’s constant pursuit of a certain truth. But instead of telling that truth, we construct a series of events, a story, which proves or discusses that truth.

When we invite the player to participate in our story, we still share that same goal, but this time, do so by creating context and purpose around a game’s mechanics - leading to an embedded narrative.

One should also treat the gameplay experience and the ‘emergent narrative’ as a tool for storytelling. But it’s a double edged sword - by allowing players to interact while scenes play out can potentially ruin them.

And lastly, having the player express themselves within the story by crafting story branches is probably the most powerful and trickiest method - players demand to see their choices have a ‘realistic’ impact, but you want each branch to feel meaningful, too.

But whether your game’s narrative involves branches or not, its story, and one can argue the entire game, is still a form of expression, by you, the author. When you begin with crafting a game’s narrative, I would urge you to start by asking yourself what it is you want to express to players. What do you want to talk about, and why?

Read more about:

Featured BlogsAbout the Author(s)

You May Also Like