The Proteus Effect -or- What We See is What We Think

If picture is worth a thousand words and games are running at 60fps, our games say a lot, very, very quickly. Even if they don't know it, our player's are listening, so let's take a look at how our words affect them.

Little preface to this article: I am going to be critical of games and of the industry at large. This is not a talk about the game culture, or the people in it, and I cannot blanket what I say further than North America, I don’t have the knowledge of the different markets and cultures.

During the MIGS16 closing Braindump “What They Don’t Tell You” Anna Kipnis, Senior Gameplay Programmer at Double Fine spoke about her experiences being a woman in the industry, and a programmer to boot. Afterwards I heard from a few of my peers how they disliked her speech.

I know I was feeling a little uncomfortable listening to her, but wasn’t sure why until a friend of mine said to me: “That talk made people uncomfortable because it wasn’t directed to us. As white males, it feels weird to not have someone speaking to us.”

That’s when it sort of clicked: There are groups who feel like that all the time; groups that are not spoken to. And yeah, saying that aloud now does feel kinda silly, it’s something obvious that I didn’t see until I looked at it in hindsight.

So, I did some research.

If you look at some of the teams a lot of them are pretty homogenous. Very few minorities and few women. The IGDA found in their most recent Developer Satisfaction Survey 81% identified as white/Caucasian/European, and 72% of their respondents identified as male. Only 23% identified as female even though women make up 40% of the player base. There’s an older root to this situation though; if I asked most people reading this why they wanted to join the industry, I feel it would be safe to assume a lot would say they wanted, at least in part, to make games that they want to play.

That’s totally cool, encouraged even. We all should be passionate about the games we make. This, however, has led to an interesting feedback loop that started back around the 80’s/90’s. The market was very competitive, so the industry needed to focus its marketing. Which in the 80’s was the young, white male demographic of middle-class, they had the money and free times for games.

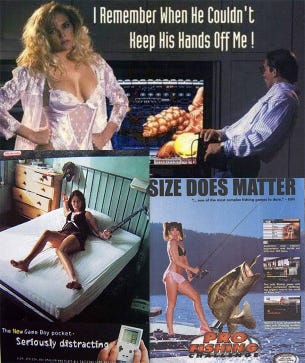

While it may have started ok, it got very very sexual, very quickly, and “sex appeal” started being used everywhere. Even Nintendo, our favorite family friendly gaming company got in on this.

While it may have started ok, it got very very sexual, very quickly, and “sex appeal” started being used everywhere. Even Nintendo, our favorite family friendly gaming company got in on this.

The loop was created – games were made for a single target demographic. They grew up playing the games they liked. Some went to join the industry and are now making games they want to play. Is this inherently a bad thing? Of course not, we should want to make games that we find interesting, but what we have unintentionally done is exclude a hugely diverse set of people, and all the experiences and views they could add to the games that are made.

The weird fact to bring up is that the idea that “boys are the ones who like tech and computers” is a relatively new idea started around the same time as those advertisements. Computers were named after those who did computations, which have been mostly women for a long time.

***

If you’re still with me, thanks, I appreciate that. Take a minute, take a sip of that drink you have. Let’s switch gears for bit. Some may be thinking what’s the problem? We miss some different points of view, is it that big of an issue? Let’s go over a small case study.

I want to look at the enemy factions you face in The Division, an open world third person shooter released last year. First we have a faction called the Rioters, which consist entirely of young men, in masks and hoodies. Sure, it’s cold, they’re committing crimes, alright. (Fun fact, this faction was initially called the thugs) Next faction we have the cleaners, sanitation workers who have decided that they need to clean the city themselves, and again, all in masks and hoodie, this time with matching vests! Then we have the Rikers, convicts who have escaped the local prison, all wearing masks and heavy jackets…

I want to look at the enemy factions you face in The Division, an open world third person shooter released last year. First we have a faction called the Rioters, which consist entirely of young men, in masks and hoodies. Sure, it’s cold, they’re committing crimes, alright. (Fun fact, this faction was initially called the thugs) Next faction we have the cleaners, sanitation workers who have decided that they need to clean the city themselves, and again, all in masks and hoodie, this time with matching vests! Then we have the Rikers, convicts who have escaped the local prison, all wearing masks and heavy jackets…

Okay, now let’s look at the helpless civilians. Not a hoodie in sight! We are shown that open, unobscured faces are good, and anyone who even remotely covers their face is bad. Hoodies are for the bad guys, and this message is reinforced through the mechanics as enemies are automatically aggressive towards the player and only show up as targets on the in-game map.

We’re creating and reinforcing a stereotype though these design decisions and this doesn’t even mention the problems that the player is given absolute authority to be judge, jury, and executioner for those they deem to be enemies. Or the idea that we are indirectly comparing blue collar workers and young adults to criminals. But this is small, subtle example, something that not everyone will notice, and was most likely not the intent of the team.

What if we look at a worse example?

The trans-women from GTAV who are over the top caricatures, treated with disrespect by all the player character. F.A.N.G. from SFV, the Asian Kung-Fu master, classically derogatory, effeminate Asian character, and how many “terrorists” have you seen?

Why does this all matter? We misrepresent a group, make a mistake, what’s the harm?

It all comes down to Identity, or “The totality of one’s self-construct, how one views themselves in the present and the continuity between their past to their aspirations for the future.” Identity is fluid and changes over time, and no matter what we think about how we are or are not influenced, the facts stand that media changes how we perceive ourselves. This effect doesn’t have to negative, but it is up to those who craft media to be aware of the potential impact, and this is where we fall flat.

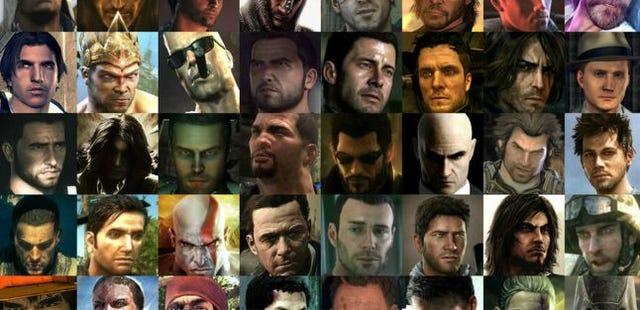

The Proteus Effect describes the phenomenon where the behavior of an individual online, will change to match the visual characteristics of their avatar. How a character looks, changes how the player will act and view themselves. This effect is a relatively new theory, first proposed at Stanford University in 2007.

This theory is influenced by behavioral confirmation, and self-perception theory, with studies that show characters created in the image of a stereotype, will change the perceptions of those in, and are the subject of those stereotypes to match that stereotype.

Here’s where the damage happens. Our players are changing how they act to fill the stereotypes we’re putting into our games, playing the role they think these characters should have, indirectly changing themselves to also fit those roles.

While the behavior does not necessarily directly persist after the play session, what does change is how the player then perceives themselves. Whatever group or character we use, we’re influence the player’s identity, and sure, when we have them play the “hero” that’s alright, but we’re only generating one type of “hero”.

Let’s break it down and bring it all back. Media affects identity, which in turn changes how an individual will behave. Behavior affects how a group is perceived and what stereotypes are created. Stereotypes are then lazy shortcuts used in media and the cycle continues. This is one complex issue our industry has, one that will take a large endeavor on both a personal and community level to fix. We need to change how we think about our medium and the impact it has.

Let’s break it down and bring it all back. Media affects identity, which in turn changes how an individual will behave. Behavior affects how a group is perceived and what stereotypes are created. Stereotypes are then lazy shortcuts used in media and the cycle continues. This is one complex issue our industry has, one that will take a large endeavor on both a personal and community level to fix. We need to change how we think about our medium and the impact it has.

Let’s talk about what can we do about it.

The first is understand there is a problem, that also means not taking offense when that problem is presented, and be mindful about what you’re developing. Next we need to watch what our content says, intentional or not. Not all cases are as obvious as what Command and Conquer has done. We are the one who are crafting these experiences, as well as the messages within them.

Last is make that game. This is the most vague of the three, it’s also an area we have the least knowledge about. I can hazard a guess on how to use race and gender to make, but I’m not the best person to do so. We don’t know how a game that features a strong female lead or a character (not caricature) of colour would do because we’ve never given them a fair chance.

I understand that all of this is uncomfortable to talk about. Race, gender, politics are, and by no means am I an expert on the subject, but if games are to continue to grow as a medium these are the topics we need to talk about, to address in our games, and our industry.

Read more about:

BlogsAbout the Author(s)

You May Also Like