Featured Blog | This community-written post highlights the best of what the game industry has to offer. Read more like it on the Game Developer Blogs.

The Power of Choices

It's been suggested that true games give the player rather than the designer power over emotion. But that's not true, in my opinion.

It's been suggested that true games give the player rather than the designer power over emotion. But I don't believe that's true. It's how much choice we give players, what that choice affects, and how the choice is resolved that gives us as designers power over a player. We present choices, and the manner in which we do so determines how they will emotionally respond.

The Interaction

First there is the player-system interaction. For example, a racing game is heavily about player-interface-interaction. The choices are about mastering the system to a desired outcome. The choice lies not in deciding what to do, but how to do it, and the emotional power of this design is in the mastery of a system, knowing what is the right choice and being able to choose correctly.

The designer chooses how to challenge this mastery, but Call of Duty employs the same emotional design principals as racing. Mastery of the system, knowing and learning how to correctly interact creates a certain player response, it allows players to feel pride, exhilaration in those moments of choice, or anger at oneself for failing to master technique. Can it possibly create more emotional response than that?

This mastery of systems includes other games like Starcraft, wherein any great player learns hotkeys, learns what to build first, necessary techniques that open up more choices further in the game, choices that in Starcraft are still limited by the necessity of victory.

The Breadth of Choice

This is how the choices we make mean within the overall systems of the game. There are narrative systems and object interaction systems, these are the two functional game elements, and both of these systems are important if the designer so chooses. The narrative is the context and aesthetic, the object-system-interaction is the functioning of the pieces within a game. This is how much choice we give a player over the systems that run a game and what the style of that choice is.

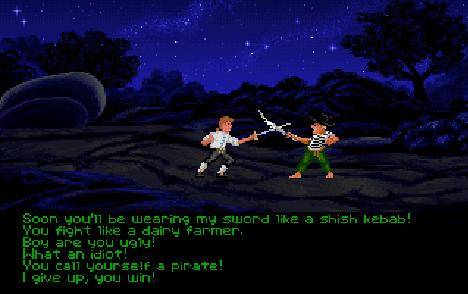

Object-level-interaction is the choice of the player on how they alter their world. A Lucasarts adventure game is usually about discovering the depths of the wordplay, the disparate objects and their uses. The inspect, open, and talk are equivalent to the shoot, pick up health, and strafe of a shooter. Schafer or Gilbert or another is working at an object interaction level where the objects are about creating emotion and laughter. Reading a line of dialog in Monkey Island lets you see the humor of the line and gives you the choice to even go further and see what that line means within the system, but reading the line alone is the power of an adventure game writer.

And therein lies the power of the designer. In an adventure game, how often are you given the choice to punch a character? Is that a function that makes sense within the system? The choice to not let you do anything but walk and talk and use miscellany to progress the story is a specific adventure game choice that seems almost necessary because it's so common.

Genres grow up around these concepts of presumably stable and clear systems. I have compared Waking Mars to Metroid in world structure to some people, because that's what they understand, but it's a grossly inappropriate comparison in every other regard.

Shooters all have cover systems now, because that's just what you do, it's a system that has been agreed upon. I have mentioned multiple times that I'd like to see more done with wider physical interaction systems. Have people made games where you fumble with your ammo clip, where handling your equipment is as complicated and taxing as shooting? Far Cry 2 has your guns jam, to make the guns themselves mean a little more, but did it go much deeper? If you made me fumble with reloading, you would create different emotional cues that might go in new directions. We have reached the end of the line on shoot or don't shoot, we know the extent of that emotional power.

How about Sim City, the creation and destruction of cities, the breadth of our choice. It's creativity and destructivity, and upkeep, choices we make not with a goal of forward movement through a linear story, rather choices Wright made that asked what you wanted, and what will you do to keep your dreams afloat. Is it possible even to do so?

And the Context of Choices is the great frontier of game designing emotion.

The context of choice is this idea that what we do within a game means or doesn't mean something. There are positive/creative choices, there are negative/destructive choices. There is the lack of choice when we want choice, there is too much choice when we're tied down to a narrow context. Sim City has some scenarios to give context, but often it's about creating our own.

Dys4ia by Anna Anthropy is great, and I love it exactly because it seems to me that the designer has chosen to limit your choice within the context of the story. You have these chapters you can play in any order, sure, but life itself when you get to the living of it, we can't help what happens. Whenever we're given any power and control at all along the path it is almost surprising. The "choice" of taking your pills is jarring, and how much choice, I wonder, do we really have?

GTA IV bothered me because the context said that I had no choice, and yet the system was wide open. I would be joyriding and ignore a call from Lil Jacob only to see a little thumbs-down appear for ignoring him. I felt like I was punished for embracing the over-arching systems the game encouraged. There was so much story to go through, they didn't want me free-roaming the city. Their story wasn't dynamic enough to uphold the beautiful and expansive and physical Liberty City. The context of my choices pushed me away from that game, disheartening me. I dropped the game because after 10 hours they had too successfully captured the responsibilities and pressures of real-life, and I didn't care anymore as I had with GTA 3.

And I always return to Minecraft, because it's always so beautiful as the example. Every choice means something. It has internal context. The context of every action builds into an open narrative that is yours. Your world may not mean much to someone else, but that chip in a stone wall you made digging some coal to create a torch has a story. The context of a choice is internal to you, yet the game rewards play by making every choice reflected in your environment. Everything is earned. Sacrifices are rewarded, mistakes are rewarded, wandering off the beaten path shows you all the more environment that you might get the urge to affect.

So What?

We give the same set of choices in almost every game we make: run, crawl, jump, shoot, build structure, collect item, but that's only a part of it. Minecraft's power over me is that the choices are often both negative and positive, build structure is part of collect item, and the emotional control that Markus Persson exercised over his game was limited, but he reimagined what those choices mean.

We can break so many more emotional boundaries if we recognize that the choices we give create emotional spaces. It's not enough to shoot or not shoot. Have we ever actually let the player put down their gun and start TALKING to the enemy? Will we ever give Gordon Freeman not only a crowbar but a voice?

Read more about:

Featured BlogsAbout the Author(s)

You May Also Like